For the first couple decades after D&D, virtually all roleplaying games looked fundamentally similar: There was a GM who controlled the game world, there were players who each controlled a single character (or occasionally a small stable of characters which all “belonged” to them), and actions were resolved using diced mechanics.

Starting in the early ’90s, however, we started to see some creative experimentation with the form. And in the last decade this experimentation has exploded: GM-less game. Diceless games. Players taking control of the game world beyond their characters. (And so forth.) But as this experimentation began carrying games farther and farther from the “traditional” model of a roleplaying game, there began to be some recognition that these games needed to be distinguished from their progenitors: On the one hand, lots of people found that these new games didn’t scratch the same itch that roleplaying games did and some responded vituperatively to them as a result. On the other hand, even those enthusiastic about the new games began searching for a new term to describe their mechanics — “story game”, “interactive drama”, “mutual storytelling”, and the like.

In some cases, this “search for a label” has been about raising a fence so that people can tack up crude “KEEP OUT” signs. I don’t find that particularly useful. But as an aficionado of Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, I also understand the power of proper definitions: They allow us to focus our discussion and achieve a better understanding of the topic. But by giving us a firm foundation, they also set us free to experiment fully within the form.

In some cases, this “search for a label” has been about raising a fence so that people can tack up crude “KEEP OUT” signs. I don’t find that particularly useful. But as an aficionado of Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics, I also understand the power of proper definitions: They allow us to focus our discussion and achieve a better understanding of the topic. But by giving us a firm foundation, they also set us free to experiment fully within the form.

For example, people got tired of referring to “games that are a lot like Dungeons & Dragons“, so they coined the term “roleplaying game” and it suddenly became a lot easier to talk about them (and also market them). It also allowed RPGs to become conceptually distinct from “wargames”, which not only eliminated quite a bit of confusion (as people were able to separate “good practices from wargames” from “good practices for roleplaying games”), but also allowed the creators of RPGs to explore a lot of new options.

Before we begin looking at how games like Shock: Social Science Fiction, Dread, Wushu, and Microscope are different from roleplaying games, however, I think we first need to perfect our understanding of what a roleplaying game is and how it’s distinguished from other types of games.

WHAT IS A ROLEPLAYING GAME?

Roleplaying games are defined by mechanics which are associated with the game world.

Let me break that down: Roleplaying games are self-evidently about playing a role. Playing a role is about making choices as if you were the character. Therefore, in order for a game to be a roleplaying game (and not just a game where you happen to play a role), the mechanics of the game have to be about making and resolving choices as if you were the character. If the mechanics of the game require you to make choices which aren’t associated to the choices made by the character, then the mechanics of the game aren’t about roleplaying and it’s not a roleplaying game.

To look at it from the opposite side, I’m going to make a provocative statement: When you are using dissociated mechanics you are not roleplaying. Which is not to say that you can’t roleplay while playing a game featuring dissociated mechanics, but simply to say that in the moment when you are using those mechanics you are not roleplaying.

I say this is a provocative statement because I’m sure it’s going to provoke strong responses. But, frankly, it just looks like common sense to me: If you are manipulating mechanics which are dissociated from your character — which have no meaning to your character — then you are not engaged in the process of playing a role. In that moment, you are doing something else. (It’s practically tautological.) You may be multi-tasking or rapidly switching back-and-forth between roleplaying and not-roleplaying. You may even be using the output from the dissociated mechanics to inform your roleplaying. But when you’re actually engaged in the task of using those dissociated mechanics you are not playing a role; you are not roleplaying.

I say this is a provocative statement because I’m sure it’s going to provoke strong responses. But, frankly, it just looks like common sense to me: If you are manipulating mechanics which are dissociated from your character — which have no meaning to your character — then you are not engaged in the process of playing a role. In that moment, you are doing something else. (It’s practically tautological.) You may be multi-tasking or rapidly switching back-and-forth between roleplaying and not-roleplaying. You may even be using the output from the dissociated mechanics to inform your roleplaying. But when you’re actually engaged in the task of using those dissociated mechanics you are not playing a role; you are not roleplaying.

I think this distinction is important because, in my opinion, it lies at the heart of what defines a roleplaying game: What’s the difference between the boardgame Arkham Horror and the roleplaying game Call of Cthulhu? In Arkham Horror, after all, each player takes on the role of a specific character; those characters are defined mechanically; the characters have detailed backgrounds; and plenty of people have played sessions of Arkham Horror where people have talked extensively in character.

I pick Arkham Horror for this example because it exists right on the cusp between being an RPG and a not-RPG. So when people start roleplaying during the game (which they indisputably do when they start talking in character), it raises the provocative question: Does it become a roleplaying game in that moment?

I pick Arkham Horror for this example because it exists right on the cusp between being an RPG and a not-RPG. So when people start roleplaying during the game (which they indisputably do when they start talking in character), it raises the provocative question: Does it become a roleplaying game in that moment?

On the other hand, I’ve had the same sort of moment happen while playing Monopoly. For example, there was a game where somebody said, “I’m buying Boardwalk because I’m a shoe. And I like walking.” Goofy? Sure. Bizarre? Sure. Roleplaying? Yup.

Let me try to make the distinction clear: When we say “roleplaying game”, do we just mean “a game where roleplaying can happen”? If so, then I think the term “roleplaying game” becomes so ridiculously broad that it loses all meaning. (Since it includes everything from Monopoly to Super Mario Brothers.)

Rather, I think the term “roleplaying game” only becomes meaningful when there is a direct connection between the game and the roleplaying. When roleplaying is the game.

It’s very tempting to see all of this in a purely negative light: As if to say, “Dissociated mechanics get in the way of roleplaying and associated mechanics don’t.” But it’s actually more meaningful than that: The act of using an associated mechanic is the act of playing a role.

As I wrote in the original essay on dissociated mechanics, all game mechanics are — to varying degrees — abstracted and metagamed. For example, the destructive power of a fireball is defined by the number of d6’s you roll for damage; and the number of d6’s you roll is determined by the caster level of the wizard casting the spell. If you asked a character about d6’s of damage or caster levels, they’d have no idea what you were talking about (that’s the abstraction and the metagaming). But they could tell you what a fireball was and they could tell you that casters of greater skill can create more intense flames during the casting of the spell (that’s the association).

So a fireball has a direct association to the game world. Which means that when, for example, you make a decision to cast a fireball spell you are making a decision as if you were your character — in making the mechanical decision you are required to roleplay (because that mechanical decision is directly associated to your character’s decision). You may not do it well. You’re not going to win a Tony Award for it. But in using the mechanics of a roleplaying game, you are inherently playing a role.

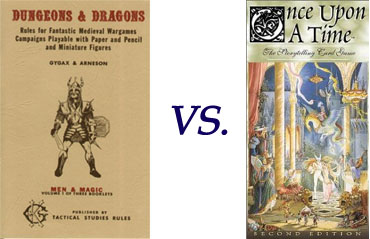

WHAT IS A STORYTELLING GAME?

So roleplaying games are defined by associated mechanics — mechanics which are associated with the game world, and thus require you to make decisions as if you were your character (because your decisions are associated with your character’s decisions).

Storytelling games (STGs), on the other hand, are defined by narrative control mechanics: The mechanics of the game are either about determining who controls a particular chunk of the narrative or they’re actually about determining the outcome of a particular narrative chunk.

Storytelling games may be built around players having characters that they’re proponents of, but the mechanical focus of the game is not on the choices made as if they were those characters. Instead, the mechanical focus is on controlling the narrative.

Wushu offers a pretty clear-cut example of this. The game basically has one mechanic: By describing a scene or action, you earn dice. If your dice pool generates more successes than everyone else’s dice pools, you control the narrative conclusion of the round.

Wushu offers a pretty clear-cut example of this. The game basically has one mechanic: By describing a scene or action, you earn dice. If your dice pool generates more successes than everyone else’s dice pools, you control the narrative conclusion of the round.

Everyone in Wushu is playing a character. That character is the favored vehicle which they can use to deliver their descriptions, and that character’s traits will even influence what types of descriptions are mechanically superior for them to use. But the mechanics of the game are completely dissociated from the act of roleplaying the character. Vivid and interesting characters are certainly encouraged, but the act of making choices as if you were the character — the act of actually roleplaying — has absolutely nothing to do with the rules whatsoever.

That’s why Wushu is a storytelling game, not a roleplaying game.

More controversially, consider Dread. The gameplay here looks a lot like a roleplaying game: All the players are playing individual characters. There’s a GM controlling/presenting the game world. When players have their characters attempt actions, there’s even a resolution mechanic: Pull a Jenga block. If the tower doesn’t collapse, the action succeeds. If the tower does collapse, the character is eliminated from the story.

More controversially, consider Dread. The gameplay here looks a lot like a roleplaying game: All the players are playing individual characters. There’s a GM controlling/presenting the game world. When players have their characters attempt actions, there’s even a resolution mechanic: Pull a Jenga block. If the tower doesn’t collapse, the action succeeds. If the tower does collapse, the character is eliminated from the story.

But I’d argue that Dread isn’t a roleplaying game: The mechanic may be triggered by characters taking action, but the actual mechanic isn’t associated with the game world. The mechanic is entirely about controlling the pace of the narrative and participation in the narrative.

I’d even argue that Dread wouldn’t be a roleplaying game if you introduced a character sheet with hard-coded skills that determined how many blocks you pull depending on the action being attempted and the character’s relevant skill. Why? Because the resolution mechanic is still dissociated and it’s still focused on narrative control and pacing. The mechanical decisions being made by the players (i.e., which block to pull and how to pull it) aren’t associated to decisions being made by their character. The fact that the characters have different characteristics in terms of their ability to be used to control that narrative is as significant as the differences between a rook and a bishop in a game of Chess.

GETTING FUZZY

Another way to look at this is to strip everything back to freeform roleplaying: Just people sitting around, pretending to be characters. This isn’t a roleplaying game because there’s no game — it’s just roleplaying.

Now add mechanics: If the mechanics are designed in such a way that the mechanical choices you’re making are directly associated with the choices your character is making, then it’s probably a roleplaying game. If the mechanics are designed in such a way that the mechanical choices you’re making are about controlling or influencing the narrative, then it’s probably a storytelling game.

But this gets fuzzy for two reasons.

First, few games are actually that rigid in their focus. For example, if I add an action point mechanic to a roleplaying game it doesn’t suddenly cease to be a roleplaying game just because there are now some mechanical choices being made by players that aren’t associated to character decisions. When playing a roleplaying game, most of us have agendas beyond simply “playing a role”. (Telling a good story, for example. Or emulating a particular genre trope. Or exploring a fantasy world.) And dissociated mechanics have been put to all sorts of good use in accomplishing those goals.

First, few games are actually that rigid in their focus. For example, if I add an action point mechanic to a roleplaying game it doesn’t suddenly cease to be a roleplaying game just because there are now some mechanical choices being made by players that aren’t associated to character decisions. When playing a roleplaying game, most of us have agendas beyond simply “playing a role”. (Telling a good story, for example. Or emulating a particular genre trope. Or exploring a fantasy world.) And dissociated mechanics have been put to all sorts of good use in accomplishing those goals.

Second, characters actually are narrative elements. This means that you can see a lot of narrative control mechanics which either act through, are influenced by, or act upon characters who may also be strongly associated with or exclusively associated with a particular player.

When you combine these two factors, you end up with a third: Because characters are narrative elements, players who prefer storytelling games tend to have a much higher tolerance for roleplaying mechanics in their storytelling games. Why? Because roleplaying mechanics allow you to control characters; characters are narrative elements; and, therefore, roleplaying mechanics can be enjoyed as just a very specific variety of narrative control.

On the other hand, people who are primarily interested in roleplaying games because they want to roleplay a character tend to have a much lower tolerance for narrative control mechanics in their roleplaying games. Why? Because when you’re using dissociated mechanics you’re not roleplaying. At best, dissociated mechanics are a distraction from what the roleplayer wants. At worst, the dissociated mechanics can actually interfere and disrupt what the roleplayer wants (when, for example, the dissociated mechanics begin affecting the behavior or actions of their character).

This is why many aficionados of storytelling games don’t understand why other people don’t consider their games roleplaying games. Because even traditional roleplaying games at least partially satisfy their interests in narrative control, they don’t see the dividing line.

This is why many aficionados of storytelling games don’t understand why other people don’t consider their games roleplaying games. Because even traditional roleplaying games at least partially satisfy their interests in narrative control, they don’t see the dividing line.

Explaining this is made even more difficult because the dividing line is, in fact, fuzzy in multiple dimensions. Plus there’s plenty of historical confusion going the other way. (For example, the “Storyteller System” is, in fact, just a roleplaying game with no narrative control mechanics whatsoever.)

It should also be noted that while the distinction between RPGs and STGs is fairly clear-cut for players, it can be quite a bit fuzzier on the other side of the GM’s screen. (GMs are responsible for a lot more than just roleplaying a single character, which means that their decisions — both mechanical and non-mechanical — were never strictly focused on roleplaying in the first place.)

Personally, I enjoy both sorts of games: Chocolate (roleplaying), vanilla (storytelling), and swirled mixtures of both. But, with that being said, there are times when I just want some nice chocolate ice cream; and when I do, I generally find that dissociated mechanics screw up my fun.

2020 ADDENDUM: TABLETOP NARRATIVE GAMES

If we can move beyond arguing that vanilla ice cream is actually chocolate ice cream, we have the opportunity to step back and recognize that these are both different types of ice cream. I propose that both roleplaying games and storytelling games are tabletop narrative games.

Now, here’s the cool thing: Recognizing that these are different things within a broader paradigm will make it easier for us to explore that paradigm. Much like having a different word for different colors makes it easier to distinguish those colors, clearly seeing the distinctions between associated mechanics and narrative control mechanics will not only make it easier for us to develop better games of those types, it will also likely make it easier for us to discover completely new types of games.

Compare this to video games, for example. Grand Theft Auto started as a maze-chase game. When they iterated on that design, nobody launched a holy war insisting that this was the One True Way of making maze-chase games. They said, “Oh. Hey. Look at this cool new type of game.” Instead of spending twenty years arguing that Grand Theft Auto 3 was a maze-chase game just like Pac-Man (and how dare you suggest otherwise?!), they identified the new form as an open-world game and spent twenty years making lots and lots of open-world games (that were in no way still trying to be Pac-Man).

Video games and board games do this all the time. And we have better and more varied video games and board games as a result. Wouldn’t it be great if tabletop narrative games could reap the same benefits?