SESSION 40B: TO THE TEMPLE OF THE EBON HAND

July 25th, 2009

The 22nd Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

After she was satisfied that the cranium rats had left, Tee snuck back to the kennel rat corral. Several collars hung from hooks in the wall. Taking one of them, she led one of the kennel rats back to where the others waited and then they passed on to the northern sewer tunnel.

Trusting Agnarr’s experience with trained animals, Tee turned the kennel rat into his care. It took a little experimentation, but Agnarr eventually determined that there were two paths that the kennel rat would follow from the northern sewer entrance: One heading towards the west and the other heading roughly eastward.

Thinking that the western one was most likely to lead to the Temple of the Ebon Hand, Agnarr turned the kennel rat loose in that direction, keeping its leash tightly in hand.

Fortunately, once set on its course, the kennel rat seemed quite certain in its path and seemed to have no desire to escape.

“For a rat it’s well-trained,” Agnarr said.

“You can’t keep it,” Tee said.

After winding through the sewers for the better part of an hour, however, the kennel rat began to wander aimlessly. Not far away, Tee spotted a half dozen hooks hanging on the wall nearby. Tee pointed them out to the others and Agnarr started playing with them, convinced that one of them must operate a secret door. After he managed to tear one of them off the wall completely, Tee pushed him out of the way and hung up the kennel rat’s leash.

“Oh!” Agnarr’s mouth widened. “They’re for the leashes!”

Tee shook her head in exasperation and started a more proper probing of the tunnel wall.

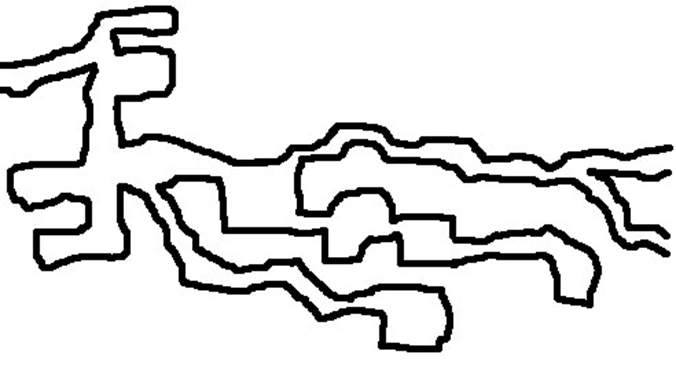

Not far away she discovered that a ten-foot-wide section of the wall was, in fact, nothing more than an illusion: She could put her hand through it as easily as insubstantial air. With a shrug of her shoulder she struck her head through: The illusion was not particularly thick and she found herself looking up an empty, ramping hall of well-constructed stone. The walls were of simple gray granite, but the floor was of a pale, whitish marble. Thirty or forty feet up, the passage ended in a T-intersection.

Pulling her head back, Tee quietly told the others what she had seen. She had also been able to hear them clearly talking behind her, so the illusion offered no sound-proofing whatsoever.

The others quieted and Tee walked through the wall. As she passed onto the white marble, the floor suddenly glowed brightly and the filth of the sewer was drawn away from her body, down through the illusionary wall, and into the sewer channel beyond.

“That’s handy.” Tee smiled, pleased that her clothes weren’t going to be ruined by the sewer after all. But she was concerned about the light, so she levitated up (with one last schlurping noise) and worked her way along the ceiling. As she neared the top of the ramp, she heard the faint sounds of laughter and raucous carrying-on from somewhere ahead. Peering around the corner she saw that the noise was coming from beyond an iron door to the right.

Deciding that it was safe enough, Tee lowered herself to the floor and padded her way to the left. The hall in that direction opened into a larger chamber with several hallways leading away from it. One side of this chamber was sunken to a depth of seven or eight feet with its open walls lined with low bookshelves. There were also a few padded chairs and a table with silver goblets and a matching serving pitcher laid out.

Tee was tempted by the silver, but decided to leave it alone for the moment. The complex in this direction seemed perfectly quiet. She returned to the others, while privately resolving not to tell Ranthir about the books so that he wouldn’t get distracted, and proposed that they tackle whatever cultists might be behind the door on the right.

Ranthir agreed. “We shouldn’t leave any enemies at our backs.”

They weren’t sure how many cultists might be behind the door, but there were certainly several of them. Since they didn’t know exactly what they would be getting themselves into when the door opened, they decided to be safe rather than sorry: Ranthir turned Tee invisible and Elestra called upon the Spirit of the City to blend the rest of them into the city’s stone (except for Ranthir, who was going to serve as the bait).

They followed Tee quietly up the ramp, their sewer filth schlorping away (Agnarr was sorry to see it go). Once they were in position, the invisible Tee threw open the door and hurled a thunderstone into the room beyond.

It landed near four cultists playing cards in the corner of a bunkroom. Each of the cultists was horribly deformed or mutated: One with huge ears; another with his left arm split into three limbs below the elbow; a third weeping acid tears; and a fourth with a patch of oozing black across his cheek and neck.

The cultists turned in confusion as the door swung open and then cried out in pain as the thunderstone went off behind them. With the echoes of the thunderstone still reverberating through the room, Tee slipped quietly to the far side of the room.

The cultist with the giant ears was howling in pain, clutching his head in both hands. The other three cultists, however, exchanged their cries of pain for those of anger and rushed the door. They saw Ranthir standing halfway down the hall and, completely oblivious to their danger, practically impaled themselves on the swords of Agnarr and Tor as they rushed forward. Tor stepped forward and finished off the third, while the fourth – still clutching his ears – lowered his hands just in time to have Tee thrust her rapier through it. (In one ear, out the other.)

CHAOS LOREBOOKS

The flurry of noise abruptly fell away. Their plan had, perhaps a little surprisingly, gone off flawlessly. Ranthir, however, had spotted the books – having backpedaled his way down the hall as the cultists came charging through the door. So while Tee searched the barracks (which proved to be of little interest), Ranthir began poking his way through the cultists’ library.

There was a copy of the Book of Lesser Chaos largely identical to the one they had found in Shilukar’s Lair and two or three copies of the Touch of the Ebon Hand which all seemed similar to the copy they had found in Pythoness House. One of the copies of the Touch of the Ebon Hand, however, had what appeared to be a prophecy scrawled on the back cover:

PROPHECY OF THE BLACK RAIN

And there shall come a night of black rain. And the arts of magic shall have no power against it. And the Gods shall be silenced. And the rain shall wash away the world that we have known and end all bonds.

The library in general was focused on matters of black magic, ritualistic anatomy, dark alchemy, and the like, but there were several other volumes of particular, specific interest regarding the mysterious Galchutt: Lore of the Demon Court, The Shadow That Never Passes, and The Bloated Lords.

Running the Campaign: One Scenario or Two? – Next: Chaos Lorebooks

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index