“Music expresses that which cannot be put into words and cannot remain silent.”

– Victor Hugo

Music at the gaming table can be as straightforward as someone clicking their favorite artist on Spotify, doing a Youtube search for “fantasy music,” or slapping their favorite CD into a music player.

But music’s role in your roleplaying adventures can be so much more than that. It can be the shorthand of the soul. It can rock the world and change the course of history. There’s a reason why the biggest celebrity on the planet is always a musician; why fight songs are blasted over stadium loudspeakers; and why you can instantly recognize the theme songs of your favorite films.

One of the things I’ve learned about music at the gaming table, though, is that it’s simultaneously soundtrack and muzak, and I think if you’re going to take full advantage of it in your RPGs, then you need to understand and appreciate both of its roles.

In its role as soundtrack, RPG music fulfills a function similar to the soundtrack of a film: It helps to set the tone and expectation of a scene and can heighten emotional investment. It can also create specific mnemonic touchstones, which can be used to reinforce familiarity, suggest structure, and even foreshadow. (“Bah gawd! That’s Vecna’s music!”)

The truth though — and maybe I’m making a false assumption here — is that I think we all have a general sense of why films and TV shows have soundtracks, how that music affects us as audience members, and, therefore, how we can use music to parallel effect during a roleplaying session.

Muzak, on the other hand, has been oft-disparaged. When I talk about RPG music as muzak, though, I’m not talking about the particular style of generic pablum that we sometimes call “elevator music.” Instead, what I’m drawing a parallel to is the function of the music that’s played in public spaces. Why does your local shop want you listening to music? Why does the customer service line want you listening to hold music while you wait? Why are Disney themeparks filled with the stuff?

The touchstone I use here is the way that music at the gaming table can subconsciously (and almost invisibly) cover the gaping void of abyssal silence whenever I need to spend fifteen seconds looking up a rule or rolling the dice.

Another is the way that you can use music to start a session: You hit play on the music (or switch from general hanging-out music to the game soundtrack) and it’s a signal to the entire table that Play Has Begun.

In this role, our session music is helping to establish a specific atmosphere the fills the room. It’s creating a broader touchstone for the game as a whole; a sense of comfortable familiarity. “We’ve been here before,” it says, reestablishing our common experience and our immersion within the game world in an instant, and then helping to maintain the continuity of that experience by lifting us up and silently supporting us even through the moments when we might otherwise stumble or become distracted.

Note: There’s actually a third function music can serve during a roleplaying game, which is diegetic — i.e., the music the players are hearing is the same music that their PCs are hearing in the game world. Diegetic music can sometimes fulfill the same functions as soundtrack (there are, in fact, diegetic soundtracks in film), but in some cases it might be thought of as something closer to prop or handout. I’m not going to be talking much about diegetic music in this essay, largely because I haven’t experimented with it very much and I think its use in RPGs is pretty rare in any case. But it’s definitely worth thinking about as an option.

MUSIC TIPS

Tip #1 – The Big Pitfall: “Wow, this two-minute track sounds perfect for the fight with the cultists!” Then the fight takes forty minutes and everyone is really, really sick of listening to a two-minute loop. I’ve learned that the absolute minimum length for an RPG loop is 7-10 minutes, and ideally more than that.

Tip #2 – Mystery Music: Try to avoid well-known and easily recognizable music that your players are familiar with. They’ll associate it with the source instead of the adventure, and that can often become distracting, too. (“Oh! I love this movie! Let’s talk about it out of character for the next ten minutes!”) The exception, of course, is if you specifically want to create and benefit from those associations (e.g., using John Williams’ Star Wars leitmotifs while running a Star Wars game).

Tip #3 – No Lyrics: Don’t use music with lyrics. Lyrics in a language unknown to anyone in the group might be okay (and can be effective at setting at the scene), but even those can be problematic. You’re playing a game entirely based on talking to each other; you don’t want your voices competing with recorded ones.

The combination of Tips #1, #2, and #3 means that what you’ll usually want to source your music from film or video game soundtracks. These are often designed to be emotionally resonant while also fading into the background under a dialogue track. (Video game soundtracks, in particular, are often designed to be seamlessly looped without becoming too repetitive.)

Tip #4 – Speaker Placement: Volume is obviously also important to avoid making it difficult for people to hear each other at the table (err on the side of the music being too quiet!), but speaker placement also plays a big role here. What I’ve learned is that there’s no One True Way here. The right solution will depend both your specific room and your players. With some rooms and groups, for example, I’ve found it works best if the music is coming from behind me (as the GM), while in others the exact opposite is true.

My current game room is equipped with surround speakers, and I can actually control the direction the audio is coming from. If your speaker placement is less flexible, though, you can achieve the same effect by simply changing where you’re sitting.

In my previous game space, I actually had the music playing from speakers in the next room, audible through an open doorway. This can be surprisingly effective in having the music be part of the experience, while being so spatially distinct that it poses no challenge to hearing.

Tip #5 – Remote Control: When the big moment comes, you don’t want to undercut it by pausing the action so that you can fiddle with your music player. You definitely don’t want to have to get up and walk across the room to swap tracks. Figure out a set up that lets you easily and seamlessly control the music. Anticipate upcoming music changes and get them cued up ahead of time, so that when the dramatic moment arrives you can tap the button without the players even realizing what you’re doing. When in doubt, ignore the music and focus on keeping the game moving. You can circle back and get the new track cued up when you have some breathing space.

In prep, this might also mean splicing multiple tracks together so that you can play them all by just pushing one button and don’t need to think about manually swapping between them during a scene.

ADVENTURE SOUNDTRACKS

For my first decade or so of playing and running games, I didn’t use music at the gaming table. Then I played in a Star Wars campaign where the GM used the movie soundtracks. Sometimes they would pick specific tracks that matched specific moments in the game. (I particularly remember them always cuing up the music for the opening credit scroll whenever they would recap the previous session.) At other times they would just let the CD play through. (This would lead to funny moments. A running joke, for example, was for bad guy music to start playing and all of the players to immediately declare, out of character, that the NPC we were talking to obviously must be an Imperial spy.)

One of the things that made this work pretty well, though, is that one of the players owned a portable CD player with a remote control and a big display you could see from across the room: The GM could load the CD up, put the player at a comfortable distance from the group, and then control it from across the room. This was a game changer! (For context: iPods didn’t exist yet.)

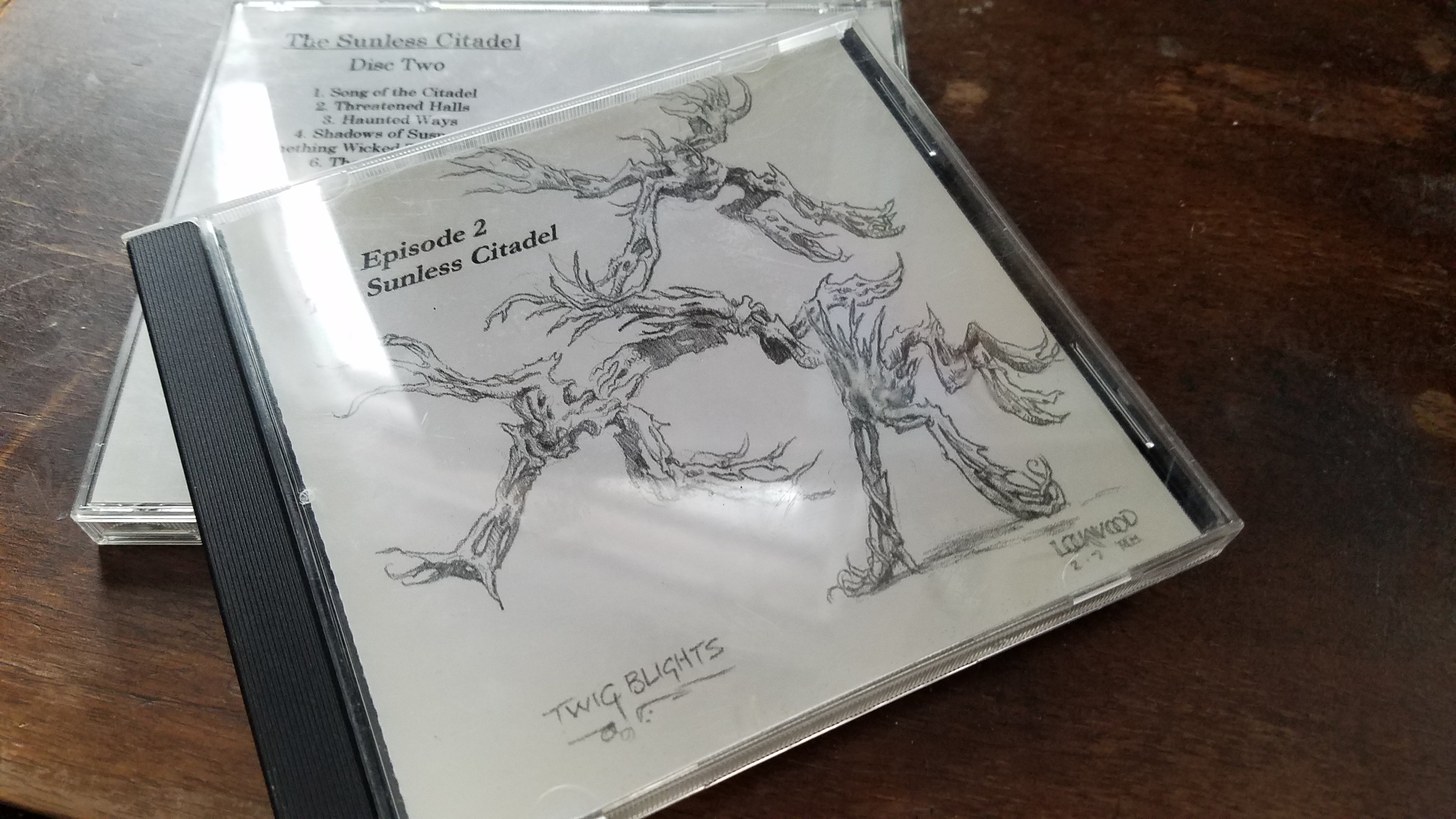

This Star Wars group ended up being the same group that I ran my first long-term D&D 3rd Edition campaign for. Having enjoyed the Star Wars music, I began prepping custom soundtracks for each adventure, keying tracks to specific events, characters, locations, and scenes. I would not only burn CDs that I could use with the CD player during the session, but additional copies — including jewel cases and cover art — that I could give to the players as keepsakes.

Creating these soundtracks was, of course, labor intensive. I’d often spend as much time prepping the soundtrack as I would prepping everything else for the session.

I’ve shared a couple of these soundtracks here on the Alexandrian, if you want to take a peek at them:

The Fifth Sepulcher

The Sunless Citadel

SOUNDSCAPES

Over time, I’ve moved away from adventure-specific soundtracks and instead prep broader campaign soundscapes. For D&D, for example, I have playlists for:

- D&D Generic Background

- D&D City

- D&D Combat

- D&D Epic Combat

I’ve been building these playlists for more than a decade, occasionally adding tracks that feel appropriate. Since I’m still the type of person who likes to actually own their music, I’ll also make a point, whenever I add a new album or soundtrack to my collection, of going through it track by track specifically to add songs to appropriate RPG soundscapes.

These playlists started out on an iPod. They now exist on my computer, and I’ve recently transferred them to a Sony Walkman for easier use and transportation between venues. You could obviously achieve similar effects with Spotify, Youtube Music, or similar streaming services, but I do, in fact, like to own and control my media. (For example, I remember a GM who discovered that a bunch of their playlists had broken when transferring from Google Play Music to Youtube Music. No thank you.)

For my long-running D&D campaign set in Ptolus, I’ve also prepped additional soundscapes:

- Ptolus – Day

- Ptolus – Night

- Banewarrens

- Banewarrens – Combat

- Chaos Cults

- Mrathrach Machine

- Banewarrens – Level 10

You can see the two base background soundscapes (Day/Night), while the other soundscapes are associated with the major arcs/villains of the campaign. The exception is the Mrathrach Machine and Banewarrens – Level 10 soundtracks, each of which were designed to accompany big finales.

Similarly, for my Night’s Black Agents campaign, I have:

- NBA Background

- NBA Action

- NBA Vampires

These, again, allow me to broadly set tone for whatever is currently happening across any number of scenarios.

To boil this down to the most basic template:

This duality may seem overly simplistic, but I’ve found it remarkably effective in practice. You can almost think of this in terms of tempo, and switching from the up-tempo action music or back to the more atmospheric background soundscape often gives you everything you need to signal major shifts in the narrative, while the random transitions between tracks don’t need to be individually managed in order to provide a little texture within the broader energy level.

You can then easily add additional soundscapes for anything that you want to punctuate something remarkable and have it really stand out from the rest campaign. (For example, by having a Vampires soundscape for my Night’s Black Agents campaign, it gives me a very clear switch to flip for something-is-different-here that can also morph into oh-crap-the-shit-is-about-to-hit-the-fan.)

Starting from the background/action duality, you may also want to split one of those into multiple soundscapes based on some other significant factor. In a D&D campaign, for example, you might want wilderness, urban, and dungeon environments to all have their own identity. In a Monster of the Week campaign, you might have a small soundscape that only plays when the PCs are gathered in their favorite tavern discussing what their plan of action is.

Going the other direction, you might also find that just having a single playlist for a campaign is more than enough. (For example, I only have a single playlist for my Numenera games.)

Tip: When creating a soundscape, make sure you listen to the entire track before adding it to a playlist! This is a lot more time consuming, but there are plenty of tracks that start out as being absolutely perfect for a background soundscape, but then midway through switch to fast-paced action, jump-scare horror, or the like. Usually you just have to let a track like that go, but I have been known — when I’ve found the perfect track except for the 30 seconds of chase music in the middle of it — to actually edit the MP3 file and create a custom version that I can use.

HIGHLIGHT TRACKS

As a kind of compromise between a meticulously bespoke adventure soundtrack and broad soundscapes, you can instead use carefully selected highlight tracks.

Basically, you key up the perfect two-minute track to set the tone of a scene or launch it with a big, dramatic bang, but then, instead of looping that single track, you transition into one of your campaign’s soundscapes.

The fun part is that you can choose to highlight almost anything.

For example, when running the globe-hopping Eternal Lies campaign, each time the PCs arrived in a new city I would play a specific musical selection handpicked for the location. Although I would then transition into my general Cthulhu-themed soundscape, I could periodically come back to the city’s theme and play it again. Done tastefully, the result gave each city a unique audio profile even though most of the music the players were hearing was just the generic soundscape. This, in turn, meant that I could play the city theme at the beginning of each session and immediately evoke a sense of tone and place.

You can also employ highlight tracks to create Wagnerian leitmotifs, which you may also recognize John Williams’ Star Wars scores. Identify the big, important characters in your campaign and assign each of them a unique theme song. When they show up in a scene, play their song. (If you’re running a social event, you could even quickly prep a playlist that includes themes for all of the NPCs who will be there.)

I’ve never actually done this, but it occurs to me you could also do this for the PCs: When someone’s PC is acting as the face for a scene or lands a big, dramatic critical hit or otherwise demands the spotlight, hit their theme song. You could even get the players in on the game (pun intended) by having them pick a theme track for their character.