DISCUSSING

In the Shadow of the Spire – Session 43E: Snakes in a Whorehouse

They found a secluded corner on the northern side of the building, well-shielded from prying public eyes, and drilled through. They found themselves in a long hallway that looked to run almost the entire length of the building. On the long opposite wall of the hall were roughly a dozen secret doors – or, rather, the back-side of secret doors. Although their construction clearly indicated that they were designed to be lay flush with the wall on the opposite side, from this side their nature and operation were plain. The hall was capped at either end by similar doors.

They had finally breached the walls of Porphyry House.

“The Porphyry House Horror” is an adventure by James Jacobs published in Dungeon Magazine #95. I scooped it up when I was looting scenarios from Dungeon during my original campaign prep: I skimmed through 40-50 issues, looking for stuff that I could incorporate into the campaign. While the PCs ended up skipping several adventures I’d pulled for Act I of the campaign, there’s a bunch of cult-related adventures that I used to add depth to Wuntad’s conspiracy/gathering of the cults in Act II.

(For some reason I started referring to the adventure as “Porphyry House of Horrors” in my notes. I had a real Mandela Effect moment when I went back to reference the original magazine for this article.)

I thought it might be useful to take a peek at how I went about prepping this adventure.

The original scenario was 30 pages long. My prep notes for the scenario, on the other hand, fill a 45-page Word document. That might sound like I completely ripped the module apart and put it back together, but that’s not really the case.

- 25 pages of my notes are actually handouts I designed for the players. (I’ll talk more about these later.)

- 10 pages are stat sheets for the adventure. This was partly so that I could use the stat sheets for easy reference (instead of needing to flip around in the adventure), and also because I wanted to adapt the stat blocks to an easier to use format.

So you can see that only about ten pages of material was actually making substantive changes to the module. And most of that was mostly dedicated to adding stuff. “The Porphyry House Horror” is just ar really great adventure. There’s a reason why I snatched it up.

LINKING THE ADVENTURE

After making a list of all the cult-related scenario nodes in Act II of the campaign — some pulled from Monte Cook’s Night of Dissolution, others from Dungeon Magazine, a couple from Paizo adventures, several of my own creation — I went through and made a revelation list with all the leads pointing from one scenario node to another.

While getting ready to prep Porphyry House, I went through this list and wrote down all the clues that needed to be available there, forming a clue list for the adventure:

- Porphyry House to Final Ritual.

- Porphyry House to Temple of Deep Chaos.

- Porphyry House to Kambranex (Water Street Stables).

- Porphyry House to White House.

- Porphyry House to Voyage of the Dawnbreaker.

(Actually, a couple of those may not have been on the list yet. I may have discovered them while prepping Porphyry House and then added them to the list afterwards. If so, however, I don’t recall which ones were which.)

At this point, these connections would have been almost entirely structural. They represent my broad understanding of the macro-scale connections between the various cults — i.e., Porphyry House is using chaositech that would be sourced from Kambranex — but I don’t know what the specific clues actually are yet. This is functionally a checklist of blank boxes I need to fill while prepping the adventure.

INTEGRATING THE ADVENTURE

With these links forged, I made a copy of “The Porphyry House of Horrors” and slid it into an accordion folder along with other adventures I had sourced for the campaign. I then didn’t touch the adventure two years. There were, after all, a bunch of other adventures for the PCs to tackle before they would get anywhere near Porphyry House.

According to the file info, I began prepping my notes for Porphyry House at 7:56 PM on August 15th, 2009. This makes sense: That’s also the date that I ran Session 41 of the campaign, during which the PCs decided that they wanted to go to Porphyry House. I would have written the campaign journal that session, and then begun prepping the scenario.

(It’s likely that I had actually reread the original adventure after Session 40, when the PCs first heard about Porphyry House. At that point they would have clearly been just a couple sessions away, and so I would have begun preparations.)

The first thing I did was figure out how to integrate the background of Porphyry House into the campaign. In this case, it was pretty straightforward:

- Porphyry House is a whore house.

- Wuntad’s first chaos cult was based out of Pythoness House, another whorehouse.

Sometimes integrating a published scenario into an ongoing campaign is tricky. Sometimes it’s more like drawing a straight line.

- “The Porphyry House of Horrors” is set in the town of Scuttlecover. I just dropped that material and picked a location for Porphyry House in Ptolus.

- I also dropped the entire original adventure hook. (I knew that the players would be getting hooked in to the cult’s activities there via the leads from other cult nodes.)

- The original Porphyry House cult was dedicated to Demogorgon. I simple palette-shifted that to a Galchutt-focused chaos cult.

- Erepodi, a minor background character from the Pythoness House adventure, was made the founder of Porphyry House. (I knew I would need to add her to the scenario.)

- Wulvera, the cult leader from the Porphyry House adventure, was given a tweaked background that synced with the lore from Ptolus and my own campaign world.

- I also knew that I wanted Wuntad to keep a guest room at Porphyry House. (This would be a useful vector for clues, and also be in accord with the Principles of RPG Villainy.)

With those details determine, I put together a very brief (roughly half a page) timeline summarizing the canonical version of events for my campaign. The original adventure also included a Gather Information table, and I adapted this to fit the new lore. (This filled the other half of that page.)

ADVERSARY ROSTER

The next thing I did was the adversary roster.

The first step was simply reading through the adventure and listing the location of every denizens. Sometimes this is all I need to do to have a ready-to-use roster, but in this case there was a lot of tweaking and adjustments that were made as I was developing the scenario. (For example, I was adding Erepodi to the adventure.)

The most significant change I made here was deciding that Porphyry House would have a different adversary roster during the Day than it would have at Night. This sort of major shift in inhabitants can be a huge pain in the ass with a traditionally keyed dungeon, but is incredibly easy with an adversary roster.

The roster was quite large, so I put the Day Roster on one page and the Night Roster on another.

PREP NOTES

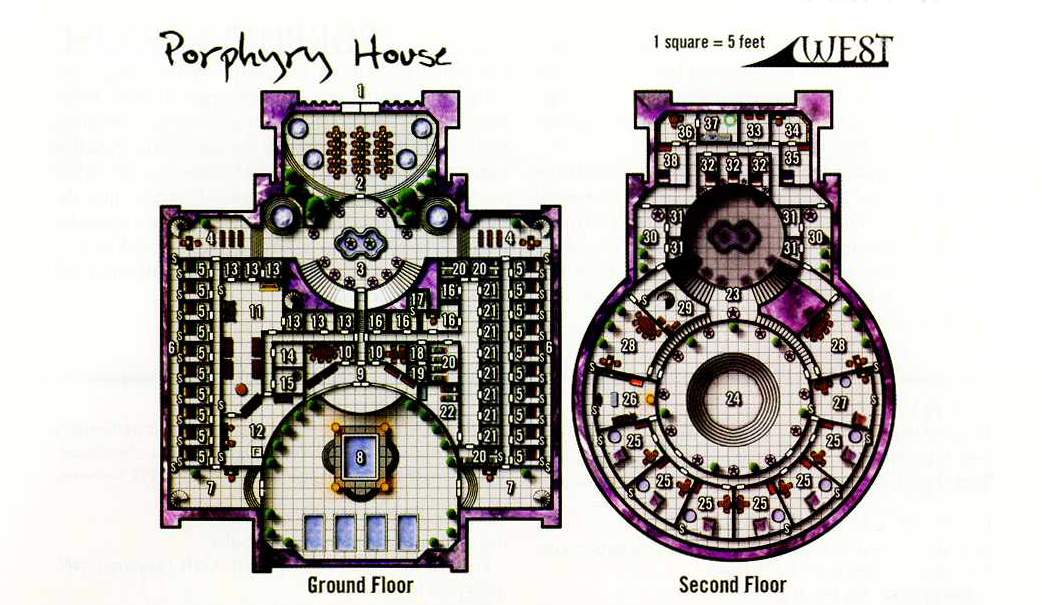

I then worked my way through the location key, making diff notes as described in How to Prep an Module. In an adventure with 46 keyed locations, I made changed to 15 of them. These were almost entirely:

- Adjusting lore (e.g., shifting the original Demogorgon references)

- Adding handouts (see below)

- Making the adjustments required for integrating the adventure (as described above)

- Adding clues to flesh out the adventure’s revelation list (mostly relating to the horrific ritual Porphyry House is making preparations for)

For example, in the original module there are four rooms all keyed to Area 16:

16. DOCUMENTS AND LIBRARY

These rooms store both idle reading material for the yuan-ti to relax with, as well as exhaustive records of their guests. None of the records have any indication that Porphyry House is anything other than a well-managed and profitable brothel, although the documents make for interesting reading; it seems that the yuan-ti keep records on everything their customers ask for…

I took advantage of this by re-keying these rooms as 16A through 16D:

- 16A was the Customer Records

- 16B was a Dark Reading Room

- 16C was Wuntad’s Guest Quarters

- 16D was Erepodi’s Quarters

In re-keying these chambers, I did things like:

- Flesh out the customer records to (a) add clues to some of the central revelations in the scenario and (b) add leads pointing to other cult nodes (e.g., sums being delivered to the Temple of the Fifty-Three Gods of Chance and “Illadras at the Apartment Building on Crossing Streets”).

- Add a selection of chaos lorebooks to the Dark Reading Room.

- Add some of the items Wuntad took from the PCs at Pythoness House to his guest room.

- Added a handout depicting a mosaic floor (with chaos cult symbols).

And so forth.

One other interesting change I made here was greatly increasing Porphyry House’s size through the simple expedient of changing the map scale from 5’ per square to 10’ per square. (I liked the slightly more grandiose dimensions this gave Porphyry House, and it also better fit the dimensions of the building I’d selected on the Ptolus city map for the location.)

HANDOUTS

Anyone familiar with the Alexandrian Remix of Eternal Lies knows that I love props. (I created over 300+ of them for that campaign.) I love handing stuff to the players because the players love it when you hand stuff to them.

For Porphyry House this included:

- A map showing the location of Porphyry House.

- Magic item references. (I frequently write these up — often including an image of the item — for any magic items the PCs find that aren’t from the DMG. It’s a fun way to make the loot feel extra special, and it’s a super useful reference the player can use for their new items.)

- Graphics depicting various NPCs and monsters. (Got a cool picture in your adventure? I will not hesitate to rip it out and give it to my players, including Photoshopping it if I need to.)

- Various bespoke lorebooks, such as Wuntad’s Notes on the Feast of the Natharl’nacna and Wilarue’s Flaying Journal. (As noted above, there were also chaos lorebooks — copies of which were spread around throughout the campaign — to be found here.)

- Various correspondence, such as Letter from Shigmaa Cynric to Wuntad and Instructions to the Madames.

Prepping handouts like these is often the most labor-intensive portion of my scenario prep, but it can also be the most rewarding.

WRAPPING THINGS UP

In practice, of course, a lot of this work is iterative: I’m updating a room key, taking notes on the handouts found there, and then bouncing back to work on more room keys. Or maybe details in one of the letters I’m writing will cause me to go back and add additional details to the background notes and timeline.

But, ultimately, this is pretty much all there is to it. At the end of this process, I had a really fantastic adventure that felt as if it had been custom-written for my campaign and my players.

Campaign Journal: Session 44A – Running the Campaign: Recalling the Lore

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index