In general, an expedition can navigate through the wilderness by landmark or they can navigate by compass direction.

NAVIGATING BY LANDMARK

Generally speaking, it’s trivial to follow a road, river, or other natural feature of the terrain. It’s similarly easy to head towards any visible landmark. The landmark or terrain feature will determine the route of travel and there’s no chance of becoming lost, so you can simply track the number of miles traveled.

IDENTIFYING LANDMARKS: If the PCs are unsure of a landmark but have had previous experience with it, it may be possible to identify it with a Wisdom (Survival) check, at the DM’s discretion. The accuracy and detail of the identification will depend on prior experience.

Example: A ranger is passing through the woods when they encounter a river. If it’s a river they’ve walked up and down before, the Wisdom (Survival) check might let them confirm that it is, in fact, the Mirthwindle. If they’re less familiar with the region, the check might tell them that this is probably the same river they crossed earlier in the day – it must be taking a southerly bend. If this is the first time they’ve ever seen this river in an area they’re not familiar with, the Wisdom (Survival) check won’t tell them much more than “this is a river.”

NAVIGATING BY COMPASS DIRECTION

Characters trying to move in a specific direction through the wilderness must make a navigation check using their Wisdom (Survival) skill once per watch to avoid becoming lost. The DC of the check is primarily determined by the terrain type the expedition is moving through, although other factors may also apply.

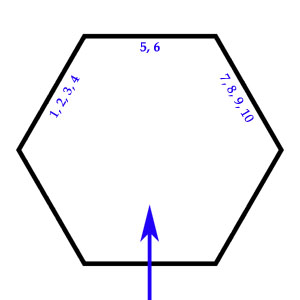

BECOMING LOST: Characters who fail the navigation check become lost and may veer away from their intended direction of travel, as indicated by a 1d10 roll on the diagram below. When lost characters exit a hex, they will exit through the face of the hex indicated by the die roll.

Characters who are lost remain lost. In the new hex neither their intended direction of travel nor their veer will change.

If characters who are already lost fail another navigation check, their veer can increase but not decrease. (If they have not yet begun to veer – i.e., they rolled a 5 or 6 on their initial veer check – then their veer can increase in either direction.)

Example: A lost party is already veering to the left when they fail another navigation check. A roll of 1-4 on 1d10 would cause them to exit the next hex two hex faces to the left of their intended direction, but any other result would not change their veer at all.

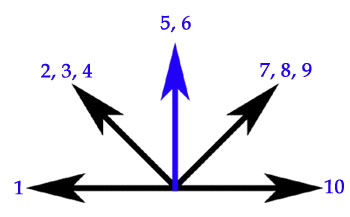

ALTERNATE VEERS: These alternate methods of determining veer may be useful, particularly if you are adapting these rules to be used without a hex map.

Absolute Degree: Roll (1d10 – 1d10) x 10 to determine the number of degrees off-course.

Compass Direction: Roll 1d10 and consult the diagram below. (The blue arrow indicates the intended direction of travel.)

USING A COMPASS: Compasses grant advantage to navigation checks. In addition, they automatically eliminate veer at hex borders even if the user doesn’t recognize that they were lost. (Even if you don’t recognize that you ended up off course, the compass constantly reorients you towards your intended direction of travel.)

LOST CHARACTERS

Once a character becomes lost, there are several factors to consider.

RECOGNIZING YOU’RE LOST: Lost navigators continue making a navigation check once per watch. If the check succeeds, they will recognize that they are no longer certain of their direction of travel.

Navigators who encounter a clear landmark or unexpectedly enter a distinctly new type of terrain can make an additional navigation check to realize that they’ve become lost.

Note: Some circumstances may make it obvious to the characters that they have become lost without requiring any check.

REORIENTING: A navigator who realizes that they’ve become lost has several options for reorienting themselves.

Backtracking: A lost character can follow their own tracks (see the Tracking watch action). While tracking allows them to retrace their steps, they must still recognize the point at which they went off-track. If a character is successfully backtracking, they may make a navigation check (using the Navigation DC of the terrain) each watch. If the check is successful, they’ll correctly recognize whether they were previously on-track or off-track. If the check is a failure, they reach the wrong conclusion.

Compass Direction: It requires a DC 10 Wisdom (Survival) check to determine true north without a compass or similar device. On a failed check, randomly determine the direction the navigator thinks is true north.

Setting a New Course: A lost navigator can attempt to precisely determine the direction they should be traveling in order to reach a known objective by making a navigation check at the Navigation DC of the terrain + 10. If the navigator fails the check, they immediately become lost. Determine their direction of travel like any other lost character.

CONFLICTING DIRECTIONS: If several characters in a single party all attempt to determine the correct direction of travel, make their Wisdom (Survival) checks separately. Tell the players whose characters succeeded the correct direction in which to travel, and tell the other characters a random direction they think is right.

Alternative Rule – Group Check: Alternatively, you can use the rules for group checks. If at least half the group succeeds on their Wisdom (Survival) checks, they have determined the correct direction of travel. If not, they immediately become lost.

FINDING LOCATIONS

The difficulty and complexity of finding a specific location within the wilderness varies depending on the character’s familiarity and approach.

Visible Locations: As described in Part 5: Encounters, some locations are visible from a great distance. Characters within the same hex as the visible location (or within a certain number of hexes, as indicated by the key) automatically spot a visible location.

On Road: If a location is on a road, river, or trail, then a character following the road, river, or trail will automatically find the location. (Assuming it isn’t hidden, of course.)

Familiar Locations: Familiar locations are those which a navigator has visited multiple times. Navigators within the same hex as a familiar location can be assumed to automatically find the location. (Within the abstraction of the hexmapping system, they’ve demonstrated sufficiently accurate navigation.) Under certain circumstances, navigators may also be considered “familiar” with a location even if they’ve never been there. (Possibilities include possessing highly accurate topographic maps, receiving divine visions, or using certain types of divinatory magic.)

Note: If navigators are flailing about in their efforts to find a familiar location – by repeatedly “missing the hex,” for example – the GM can decide to treat the location as being unfamiliar until they find some way to reorient themselves.

Unfamiliar Locations: Unfamiliar locations (even those a navigator has been to previously) are found using encounter checks.

In other words, when the navigator has gotten the expedition into the correct hex and a location encounter is generated, that indicates that the navigator has found the location they were looking for. Expeditions can also spend time to specifically search an area in order to increase the odds of finding a location. See Part 7: Hex Exploration.

Hi Justin

Really enjoying this series

Admittedly AAW have just completed their KS on reviving the Dungeoneers Survival Guide…. which will be full of spelunking goodness….

However, if you have any further thoughts on Underdark hex crawls beyond your 2014 article, I am keen to hear it! Thanks, Ben

Great post!

Two quick questions…

(1) If the players are navigating by compass direction, how do you handle them saying “I intend to head East/West”?

I understand that you keep the hex grid itself hidden from players. Without knowing they are playing on a hex, how would folks know that east or west is not possible?

(2) Assuming the players are making their rolls publicly, how do you avoid metagame issues in the case of conflicting directions? It would be obvious to the players which the more correct direction is…

@Rahul:

(1) I believe these alternate rules are not supposed to be used with hexes. But if you want, it’s possible to mess with progression required to leave the hex and some other things to adjudicate a North/South movement.

My players were always aware that they have 6 directions to go, and that I’m using hexes (after all, I sold the game as an hexcrawl). They just don’t see the hexes, don’t know the scale, etc. For instance, they are using 5 miles/hex on their maps, but I’m using 12 on mine.

(2) When the players figure out they are lost, they never know if they got lost, “straight”, “clockwise” or “counter clockwise”. The veer is determined by the DM in secret.

@Rahul:

Going East or West is possible on a hexmap. If the hex above is oriented such that the arrow is northernbound travel, then a party entering the hex from the “1,2,3,4” side and leaving it through the “7,8,9,10” side is travelling exactly perpendicular to that from west to east.

@Justin

I think it would be helpful to have a breakdown of how players articulate common navigation choices, and how you translate that into the system. East-West when that passes through a vertex instead of a side is one case.

From what I understand, recognizing lost and trying to set a new course still gets you going in a closer direction even on failure, because you’ll at max only be veering by hex again.

5E doesn’t have a take 10 or take 20 mechanic, but it does have passive checks that take the average. Does the system support those, and is there a reasonable cost to doing so (encounter check)?

Another question (problem part 7 material), is what happens if players want to drill down and deeply explore a section of the map, but where the search radius includes several adjacent hexes.

It’s a complex system and I think a some simulated actual play would help a lot.

@Rahul:

(1) I think I’m actually going to do an addendum on this, because it’s a frequently asked question. But essentially you “bias” your position in the hex:You determine if the group is in the northern or southern half of the hex (which can be done fairly easily based on where they’re traveling from and the progress they’ve made through the current hex) and then you can basically draw a straight east/west line that will clearly indicate which hexes they’re passing through.

The veer diagrams, etc. still work just fine because they east/west line of travel clearly indicates which hex face they’re aiming to exit through.

More generally, the conceptual mistake is thinking of travel from one hex to another as always originating from the center of one hex to the center of another, which creates the impression that east/west travel on a hex map is a zig-zag. But the whole reason you’re using the hexmap is to abstract movement: We don’t really know where the PCs are in the hex (even if we’re tracking progress and, therefore, have a limited indicator that we can use to our advantage if we so choose); it’s more like a smear of quantum probability.

(2) If metagaming of roll results that the characters don’t have the associated knowledge to determine is happening, the solution — as always — is to make the rolls secretly. I try to avoid that, because it can easily decay into “watching the GM roll dice with himself.” But as long as you make sure to emphasize the navigational and circumstantial decisions in each watch, it’s just fine.

As others have noted, the veer roll SHOULD be made secretly. And the system is designed to obfuscate what a poor roll means: Even if you roll poorly and know that you’re probably lost, there’s a 20% chance that you haven’t veered and are still more or less heading in the right direction.

@Jin: The more I run 5th Edition, the less I like passive Perception being handled as a static value, but this system works just fine with that. I would not introduce passive scores to navigation or forage checks. (Doing so for navigation checks, for example, would mean that characters would just automatically be Always Lost or Never Lost.)

In terms of “searching area larger than a single hex,” the image to keep in mind is establishing a base camp and then exploring the surrounding area. If the area you’re searching is bigger than a single hex, though, you’re talking about distances larger than “go out, search, come back to camp” in a single day. So you’re talking about moving your base camp… which is just another way of saying that you’re engaged in wilderness travel (and should use the rules from moving from one hex to another).

Might be an edge case in there for very fast, magical movement. But probably still breaks down as a watch spent traveling, a watch spent taking an exploration action, and another watch spent traveling back to your base camp.

@Justin thank you, that makes a lot of sense!

Last piece I’m trying to wrap my head around is this: “ Example: A lost party is already veering to the left when they fail another navigation check. A roll of 1-4 on 1d10 would cause them to exit the next hex two hex faces to the left of their intended direction, but any other result would not change their veer at all.”

Do you possibly have a diagram to show what this means visually?

Personally I’d love to see you run a hexcrawl on one of your actual-play videos. The mechanics are important but I’m still really curious what kind of experience that generates at the table. Like, one big question for me is, how fast is this supposed to run? How much time is spent on the mechanics of moving from hex to hex, setting watches, etc. etc. vs. resolving encounters? How many hexes does the party move through in an hour of session time?

@Rahul: I’ll try to sketch up a diagram, but to reference the veer diagram:

1. The intended direction of travel is towards the 5,6 face. (“We want to head north.”)

2. They get lost and roll 3 on their veer die, so now they’re ACTUALLY heading towards the hex face labeled 1,2,3,4 (the northwest face).

3. They exit the hex through that face and are now in a new hex. In that hex, their intended direction of travel remains north (towards the 5,6 face), but their veer is also unchanged. They are heading towards the NW face (1,2,3,4). If nothing changes, they will exit the second hex through that face.

4. But they fail another navigation check, so they have to roll another veer die. If they roll 5-10 on this veer die, nothing changes (they’re still heading for the NW face). If they roll 1-4, their veer increases: They are now heading toward the SW face of the second hex.

There are two reasons for this: First, rolling a bunch of dice so that the PC’s veer just cancels itself out without them ever realizing it is a lot of work for a really boring result. Second, it turns out that people lost in the wilderness generally DO walk in circles, so there is a rough approximation of reality supporting this.

@Samantha: Definitely on my To Do list. Not sure when it will Get Done, though. 😉

@justin: “you can basically draw a straight east/west line that will clearly indicate which hexes they’re passing through.”

In that case, assuming the players are trying to go west and are not getting lost (following a east/west road, for example), the progression required to cross an hex should be reduced?

They’ll be always crossing to a far side, but requiring 12 miles per hex will make them travel considerably slower than they would in a north/south direction.

I’m experimenting with your hexcrawl method for a while now using OD&D. But my players are constrained to the 6 basic directions, and I think that sacrifices the immersion a bit.

@Kaique: It’s not a standard for gaming maps, but you could always experiment with using octagons instead of hexagons for the map.

That might create a lot of upfront work to get the map translated, but would eliminate being fuzzy on which side is a particular compass direction.

Which I guess leads me to ask, what led us to use hexagons and squares as the standard for maps in RPGs?

Let me see if I’ve got this straight:

Suppose the players are attempting to travel due west. Their starting point is in the northern half of a hex, so they leave that hex through the NW edge, entering the next hex via the SE edge. In that hex, however, the navigator fails his check and they begin to veer left, exiting through the southern edge. Assuming their veer doesn’t increase in the next hex, they will exit that hex through the SW edge. Is that a correct interpretation of the rules?

@forged: The problem with octagons is that they don’t tesselate. You end up with a lot of tiny squares in-between, and that would *really* complicate determining location and distance. If the fudging required for east-west travel on a hex map bothers you enough to care, you’d be better off just using squares. The main problem with that is calculating distances for diagonal travel. The diagonal of a square is the side multiplied by the square root of 2, but rounding it off to 1.5 is probably close enough for practical purposes.

As for the reason why we use squares and hexes, a square grid is easy and obvious. Per Wikipedia, “The primary advantage of a hex map over a traditional square grid map is that the distance between the center of each and every pair of adjacent hex cells (or hex) is the same.”

@Wyvern: Good point. Clearly, I’m not that awake today. Thanks.

Kaique: In that case, assuming the players are trying to go west and are not getting lost (following a east/west road, for example), the progression required to cross an hex should be reduced?

In short, probably not. In unit lengths:

Side = 1

Face-to-Face (north-to-south) is a short diagonal. It’s 1.732.

The widest point (east-to-west) is a long diagonal. It’s unit length 2.

So you might think, “If they’re moving east-west across the narrowest point of the hex, that’s a significantly shorter distance!” But if you look at the hex map, if they’re moving east-west at the shortest width of one hex, then they’re moving at the widest length of the next hex.

If that’s the case the distance will average out to 1.5. Which, yes is less than 1.732, so it’s true that east-west movement will only about 10.5 miles per hex instead of 12 miles per hex.

But the “error” only accumulates to a full hex difference in a straight line run of 9+ hexes. These kinds of straightline runs are unusual IME. And if you’re using the advanced rules for variable travel distance, it gets completely washed out in the statistical noise regardless.

@Wyvern beat me to the tessellation punch, but for those interested, there are provably only 3 single-shape (“regular”) tilings of a plane (why does nobody ever champion the poor forgotten triangular grid?). Wikipedia has some lovely images: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euclidean_tilings_by_convex_regular_polygons. I wonder if using a k-uniform tiling for your map (with no corrections for distance) could be a useful approximate way to represent travel in a non-Euclidean space.

@Kaique and @Justin: In a fit of foolishness, I once actually ran this 87% correction rule for east-west travel on a hex map. You will be unsurprised to learn that I found it to far more trouble than it was worth.

@justin: Thanks for the detailed explanation. I was considering a progress of 21 miles for every two hexes, but you made made me realize that, for the 10×10 hex map I use, it’s not worth the effort. Apart from that, the hexes don’t allow a “true” diagonal (NE/SW or NW/SE) either, and the calculations required to correct that are beyond what I’m willing to do.

Consistently refreshing for the next one xD

I might be being silly, have we been told the forage or navigate DCs for different terrain types?

Navigation and Forge DCs are in Part 2.

Also available for Avernian terrain.

Hi Justin!

This is an old post, I know, but i was looking for some clarification. “Under Setting a New Course”, you say that they navigator should make a check “at the Navigation DC of the terrain + 10”. Do you mean that they have +10 to the check, or that the DC has +10?

Hi Justin. This series (and the original) have been hugely inspirational to me. I’ve started keying my 12×12 map and I find myself wondering – how do you handle players wanting to travel off the map? Say they’re on the eastern edge and want to keep going east. Do you tell them that they’re leaving the prepared area, or just start mapping out ahead of them/making it up?

I know this is an old post and if any fellow readers remember him describing his approach to this please let me know! I can always just address this when it comes up but I’d like some wisdom from an experienced source (I’ve never run a game in this way).

@Nick: Add more hexes.

I’ll generally improvise during the session and then, since it’s now an area they appear to be interested in, spend some time prepping more hexes in that direction after the session. In this way, your hexmap will organically grow over time.

If you’re less comfortable improvising, you can give yourself some resources to draw from. For example, could grab a bunch of blank Dyson Logos maps, print them out, and keep them in a folder. When you need to fill an unkeyed hex, grab a map, generate two monsters, and use the Goblin Ampersand technique to quickly stock it.

(Call a five or ten minute break if you need to.)

I was reading comments about how the hex doesn’t represent traveling east or west, only one ne or nw and se or sw, and I had an idea.

You would need a virtual table to do this but why not rotate the hexes depending on which way they choose to travel? If they want to go north, the flat side is on the top of the hex. If they want to go west, rotate the hexes so west has a flat side (and the pointed side on top). If they want to go south afterwards, rotate the hexes back to the original orientation. You might need two different keys for the hexes but wouldn’t everything be in the same general area?

See my reply at #6.

Rotating the hexes is an interesting idea, but a lot of hassle to try to solve something that can be trivially handled by drawing a straight line across your hex map.