Go to Part 1

Scott McCloud is better known these days for Understanding Comics, one of the greatest books ever written about art and the creative process; a towering achievement which laid bare the heart of the comic book medium.

Scott McCloud is better known these days for Understanding Comics, one of the greatest books ever written about art and the creative process; a towering achievement which laid bare the heart of the comic book medium.

(You may have seen me previously discuss Understanding Comics here, here, here, or here.)

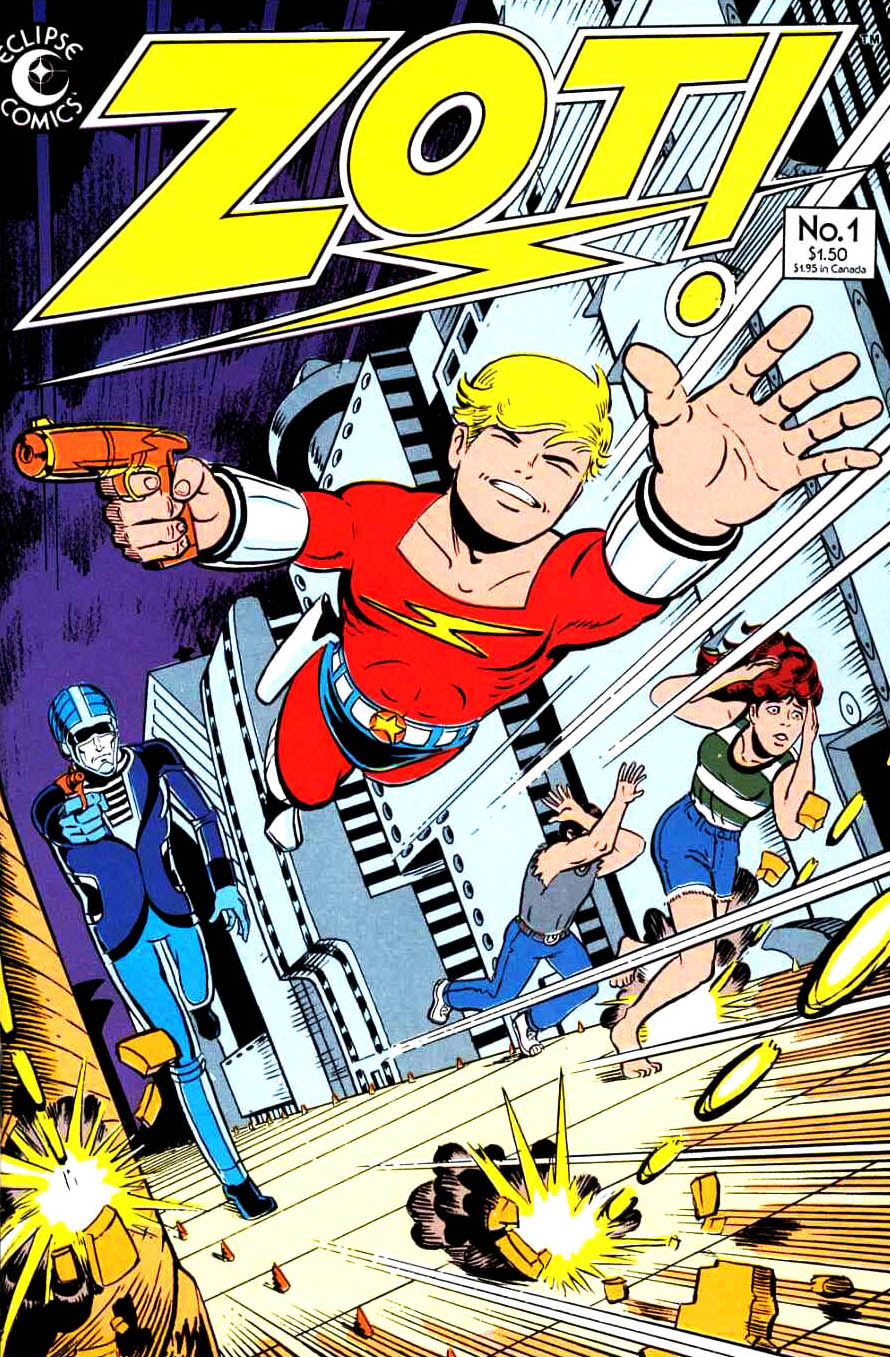

Before he created Understanding Comics, however, McCloud created Zot!, one of the greatest superhero comics ever written. The first ten issues of Zot! – the so-called “color issues”, because the rest of the series transitioned into twenty-six black-and-white issues – are a must-read superhero / science fiction epic. And it’s here that we find our third scenario structure challenge.

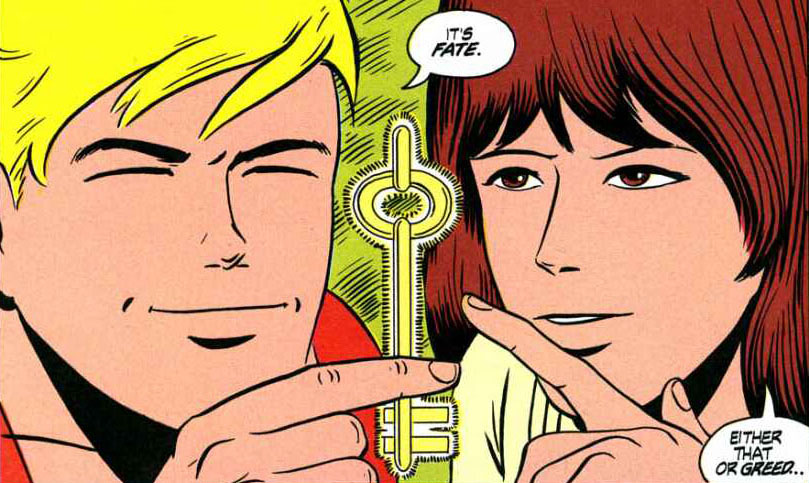

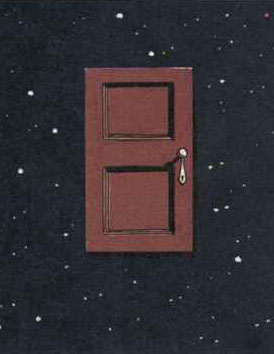

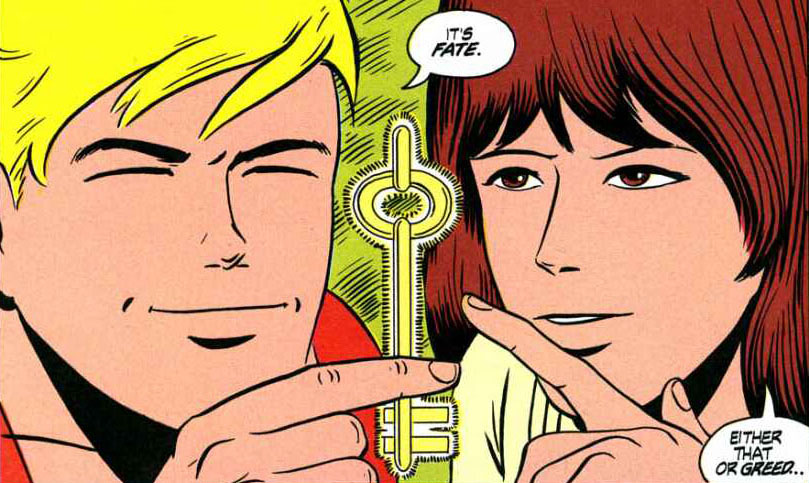

At the heart of Zot! is the Key:

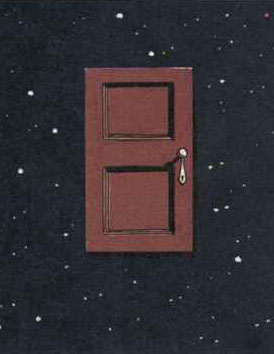

Not quite a McGuffin according to my stuffy, traditionalist definition of the term, although largely indistinguishable from such for the first six or seven issues of the story, and close enough for our  purposes in any case. The Key is a holy relic held sacred by the people of Sirius IV and said to be capable of opening the Doorway at the Edge of the Universe.

purposes in any case. The Key is a holy relic held sacred by the people of Sirius IV and said to be capable of opening the Doorway at the Edge of the Universe.

The Key has also been stolen.

As the series begins, Zot chases the Key (or, more accurately, the trail of people looking for the Key) through an interdimensional portal to our Earth. There he meets Jenny, and through a series of hijinks they end up forming a small team of unlikely heroes who are pursuing the Key.

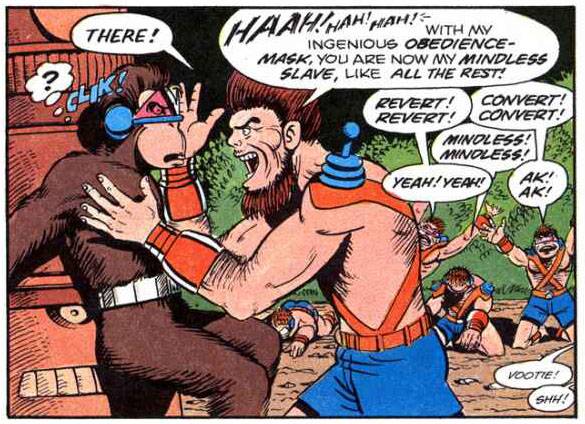

But they aren’t alone. In addition to the original owners and the thief, now that the Key is out in the open a whole bunch of factions have become interested in acquiring it. The first few issues of Zot! each have a procedural heart to them, in fact, with Zot needing to deal with some different crazy foe who wants the Key for themselves.

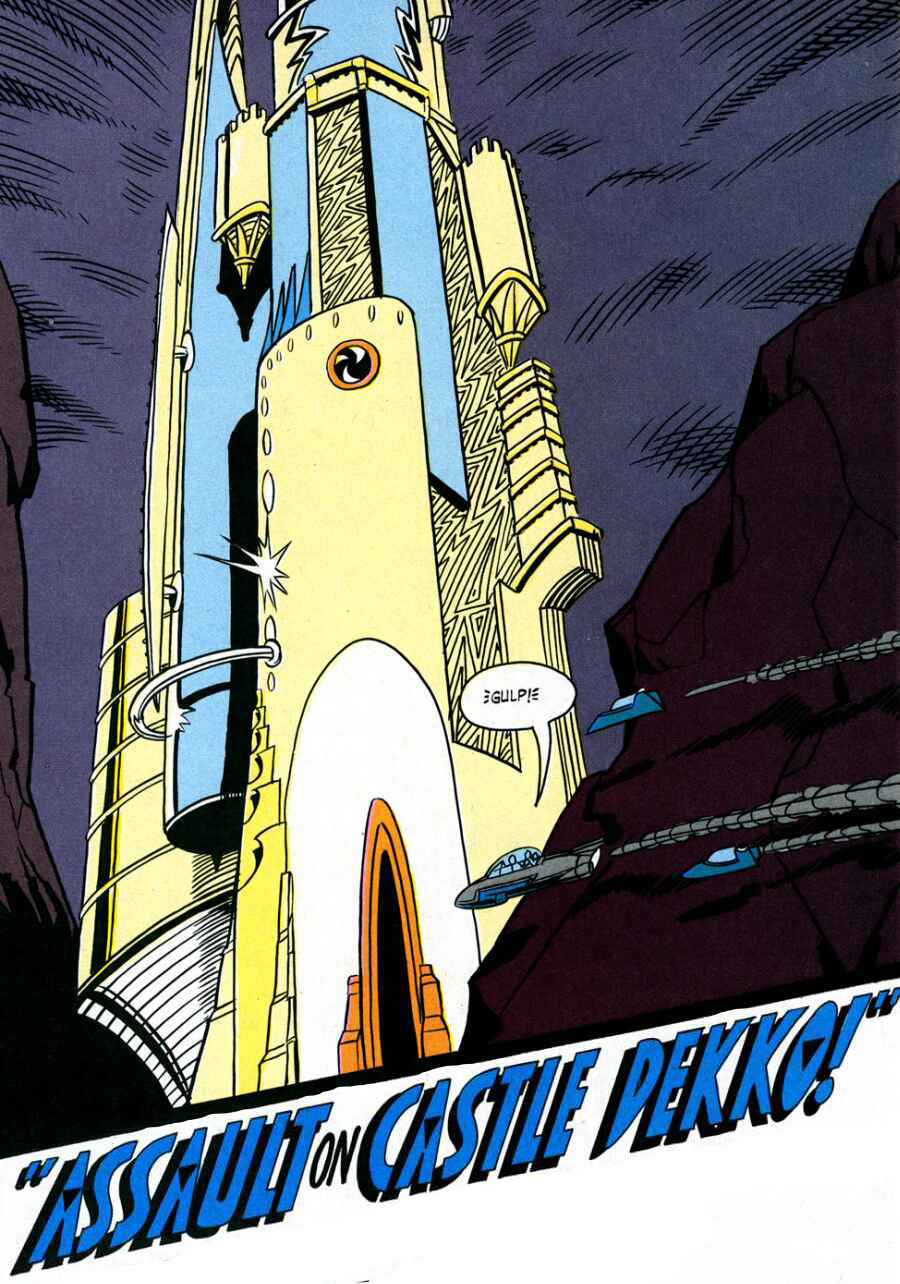

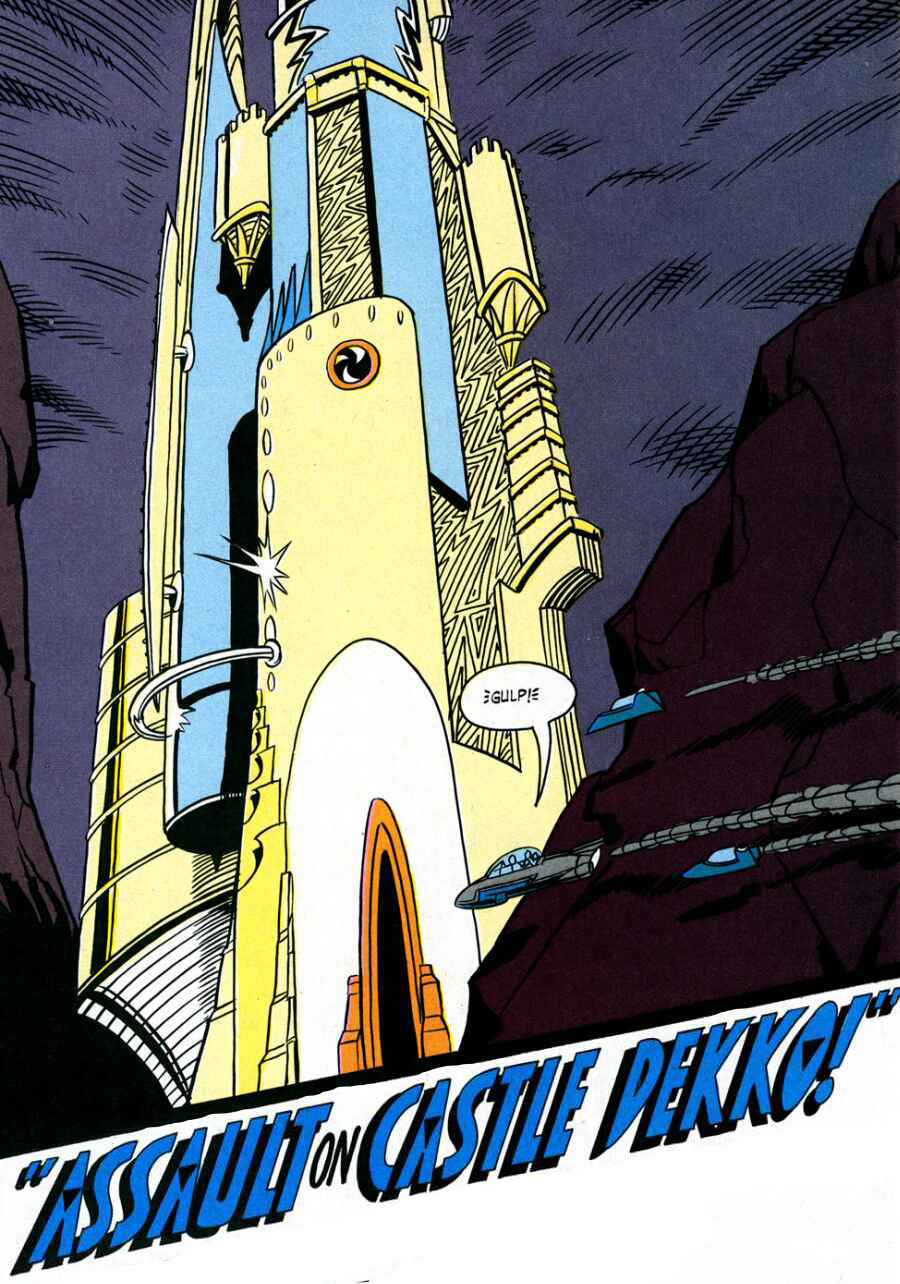

This includes Dekko, a Machiavellian machine who believes that the Doorway – a product of technology which predates all technology – is the “final ascendancy of Man’s perfect art and the end of Man’s greatest flaw: Himself.”

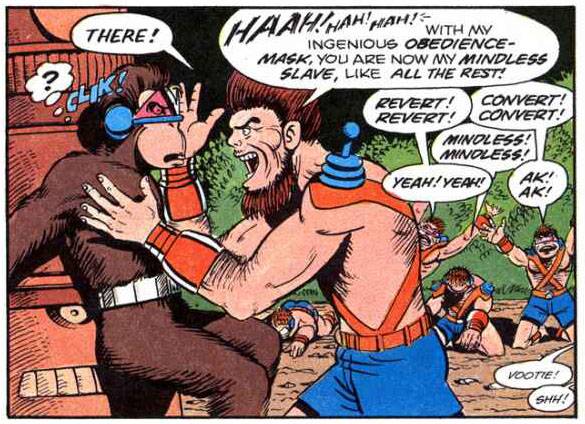

There are also the De-Evolutionaries, who believe that humanity would be better off if it went “back to the trees” (and use de-evolutionary guns to turn people into chimps to make that literally happen). They want the Key because passing through the Doorway will legitimize their crazed religion.

Where the story becomes truly special, however, is when these different factions begin collapsing back into themselves; interacting with each other, forming and breaking alliances with each other, and developing complicated and rich relationships with each other (and with the object of their desire).

McGUFFIN KEEP-AWAY

This scenario shares a lot in common with the Race to the Prize that we analyzed last week: A target object of value with multiple factions competing for its ultimate possession. The key difference (pun intended) is that rather than being the ultimate goal of the scenario, in Zot! the McGuffin is in play and actively shifting possession over and over again.

In the case of Zot! the initial scenario hook is that the item has been stolen. But you can just as easily have the McGuffin secured and instead have the initial scenario hook be the need to steal the item, which then initiates the McGuffin Keep-Away. To some extent the distinction is merely one of perception, however, since the structure ultimately boils down to “X currently has the item, who can take it from them?” The “original owner” of the item is just the one currently in possession of it.

This keep-away dynamic makes the scenario more difficult to design and run. Without the clue trail of the treasure hunt, creating a through-line for the scenario becomes more complex. It also becomes trickier to clearly set up rivalries and the competition between teams, because in the default mode there’s no sequence of events that needs to be achieved before snatching the prize. And as soon as somebody (whether it’s the PCs or somebody else) snatches the prize, they’ll be in the wind.

Okay, so what makes this scenario work?

1. Create X number of factions seeking the McGuffin, in a process that will be fairly similar to that used for Race to the Prize.

Zot! features a couple of interesting variants here. First, there are a number of proxies who end up shifting their alliances (or, at least, which faction they are currently working with) several times throughout the narrative. Second, there are entire secret factions which are using other factions as a front for their own activities. The character of Prince Drufus, for example, notably ends up  as both. In fact, he frequently ends up working with the PCs (Zot, Jenny, and their friends) – sometimes because their goals are in accord; sometimes unaware that they are not; and sometimes despite the fact that he knows they are not.

as both. In fact, he frequently ends up working with the PCs (Zot, Jenny, and their friends) – sometimes because their goals are in accord; sometimes unaware that they are not; and sometimes despite the fact that he knows they are not.

In this, Zot! also highlights the value of giving the factions distinct ideologies which nevertheless overlap with each other. Let’s call these Venn diagram alliances: It’s a powerful technique because the points of commonality will drive the factions to work together, while the points of difference will create conflicts within those alliances which will eventually rip them apart. Remember that this includes the PCs! And, furthermore, remember that you, as the GM, don’t need to determine what the PCs’ agenda will be. These types of ideologically complex environments are great specifically because they force the players to make tough, meaningful choices.

One easy format for these ideologies are characters who desire the same outcome but disagree about how it should be accomplished. (And, inversely, those who desire different outcomes but currently agree on the necessity of a particular course of action.)

2. The keep-away. For each faction, you’ll want to know what tactics they use to steal the McGuffin (stealth, force, etc.) and, if they succeed in obtaining the item, what tactics they’ll use to secure  it. Often this can be improvised during actual play, but if you’re unsure about improvising this sort of thing then prep exactly how each team will operate and what they will do (particularly when it comes to securing the item). And, of course, some of these elements will require prep for maximum effectiveness.

it. Often this can be improvised during actual play, but if you’re unsure about improvising this sort of thing then prep exactly how each team will operate and what they will do (particularly when it comes to securing the item). And, of course, some of these elements will require prep for maximum effectiveness.

Dekko, for example, retreats to his fortress of Castle Dekko for defense. Another thief uses technological camouflage to hide in plain sight. Prince Drufus has a squad of attack robots at his command. The methods and resources you can design here – both mobile and static – are pretty much limitless, and you’ll want to try to vary things between factions. If everybody is just a squad of goons who then retreats to a fortified position, the scenario will become considerably less interesting.

3. The method to find the item. This is the dynamic that’s tricky to get right, but on which the whole scenario structure really depends. Because, as noted before, if somebody can grab the item and then just trivially disappear, the scenario just doesn’t work.

Zot! addresses this problem by giving the Key a unique radiation signature which can, with some expertise and knowledge, be used to track its general location. This includes tracking it to different planets and also into other dimensions, so there really is no way to escape and take the Key “off the board” (so to speak).

Eventually, however, someone figures out how to cloak this radiation signal. This forces the other factions interested in the Key to intuit what the current holder of the key will use it for (i.e., opening the Doorway at the Edge of the Universe), allowing them to once again zone in on it (i.e., put the Doorway under surveillance and security).

Relying on this kind of intuition can be a little risky when it comes to RPG scenario design (since you can’t control exactly what your players will think of or when they’ll think of it), so for a more robust scenario you’ll want to use the Three Clue Rule. Remember that your clues can include intelligence from other factions that have made the intuitive leap. (“It looks like Indiana Jones is heading for Moscow. He must know something we don’t, let’s follow him.”) The web of alliances between factions can also allow you to become proactive here by having other players approach the PCs with an offer to work together (or simply slip them information they feel will be to their advantage).

The more general realization to make here is that this method of discovery very easily collapses into a chokepoint, and like any chokepoint it becomes a potential weak spot at which the scenario can break. If, for example, you design the scenario so that the PCs need to make a test in order to detect the Key’s radiation and they fail that test, that can very easily turn into the PCs having no idea what to do next.

So you want to avoid that chokepoint. In many ways you can think of this as the default action of the scenario (if the PCs have no idea what to do next, they can attempt to find the current location of the item). You’ll either want to make that default action automatic (so that failure isn’t possible), make it meaningfully repeatable (so that there’s a cost to failure, but you can always try again; a partial success test is another way of accomplishing this); or multiply it (so that if one method fails, the PCs can try another method; this would be a variant of the Three Clue Rule).

4. An endgame, usually in the form of an ultimate goal to be achieved with the item – delivering it somewhere, using it for something, preventing others from using it for a certain amount of time, or maybe just figuring out how to definitively destroy it or hide it so that other factions can’t use it. (This last point, of course, flies in the face of #3, so it should require significant effort of some sort in order to achieve this, giving other factions plenty of time to interfere before the endgame is truly achieved.)

Without some form of definitive endgame, the scenario will never end: The McGuffin will just continue being endlessly passed around. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but what it usually means is a growing sense of frustration and futility as the scenario chews up its inherent interest but continues hanging around without any satisfactory resolution.

One variant to look at here is a PC-specific endgame: The great game surrounding the McGuffin continues, but the PCs have accomplished whatever their goal regarding the McGuffin is and are content to exit on their own terms.

SIMPLIFY THE STRUCTURE

Zot! is big and it’s complicated. The scope is multidimensional and multiplanetary, with time travel complicating things even further and the fates of entire worlds at stake. Rather than immediately tackling something of this scale, it might behoove us to take our scenario structure out for a test drive with something a little more modest.

Let’s try this: The Maltese Falcon has, at long last, been found. Its value is immense, but particularly so to the practitioners of the ancient rites of magick, who know its true purpose. It has been placed as a lot in highly exclusive, black market auction that takes place aboard a small, ultra-luxury cruise ship on the high seas.

Let’s try this: The Maltese Falcon has, at long last, been found. Its value is immense, but particularly so to the practitioners of the ancient rites of magick, who know its true purpose. It has been placed as a lot in highly exclusive, black market auction that takes place aboard a small, ultra-luxury cruise ship on the high seas.

This premise allows us to further control the scope of the scenario: Barring extraordinary efforts, the action will be confined to the ship until it comes back into port. Neither the PCs nor anybody else will be able to vanish as soon as they’ve stolen the Falcon.

In addition to deck plans for the ship (which you can probably find online), you’ll also want to prep:

1. The factions involved. This will include the current owner of the Falcon and the security team for Penumbral Holdings, the mysterious organization behind the black market auction. Let’s also toss in a couple of sorcerous sects plus a team of mundanes (who just want the Falcon for its jewels and are way out of their depth here).

2. For the keep-away, you’ll want to prep the initial auction-related security protecting the Falcon. Maybe the PCs are the first ones to steal it, maybe they’re not. Either way, you’ll want that initial condition.

3. For the next step, we need to take a step back and think about how we want to organize our prep for this boat. I’m going to argue that we can prep the week at sea as a big social event, using the party planning scenario structure. Parties are usually short affairs, but the structure can easily be expanded to multiple events over several days. Nick Bate and I did something similar for the second part of the Quantronic Heat mini-campaign for Infinity.

With that knowledge in our pocket, we can now consider the method to find the Falcon. For the sake of argument, let’s say we’re running this scenario with Fantasy Flight’s Genesys system. In that case, we might look at something like this:

- You need to achieve X number of successes over any number of checks in order to figure out who currently has the Falcon. Primary checks would focus on social interactions with the other factions onboard. Investigating where the item was stolen from could also contribute additional successes. (Alternative methods might also include sorcerous divinations.)

- Advantages on these checks can be used to determine aspects of how the item is currently being secured (guards, security measures, etc.).

- Disadvantages or Despair might alert one or more of the other factions about the PCs and their intentions. Or attract the attention of Penumbral Holdings’ security team.

4. Our endgame here is simplified by the constrained premise we’ve used: When the ship makes landfall, whoever is currently holding the Falcon will most likely be able to vanish without a trace. The goal of the PCs is to be the one holding the Falcon when the clock runs out.

A possible wrinkle on our endgame is a simple question: Why would Penumbral Holdings put the ship into dock if the Falcon is still missing?

The primary explanation might be exigent circumstances: There may be people onboard that Penumbral Holdings can’t afford to piss off. Or the sorcerous wards preventing teleportation might expire at the end of the week no matter what. Or the true nature of members of Penumbral Holdings prevents them from remaining on the material plane of existence for more than a week.

Alternatively, this might become part of the action: Those holding the Falcon (including the PCs) may need to hijack the ship and bring it into port so that they can make good their escape. Or there’s a rendezvous craft that’s going to arrive at such-and-such a time.

RUNNING THE KEEP-AWAY

The spine of our Maltese Falcon scenario is the social event, advice for which can be found in the original Party Planning article. For the factions, you’ll probably want to prep progressions like those we discussed last week in Race for the Prize.

The social event spine is really a crutch of sorts, giving you a firmer structure to fall back on and build the McGuffin Keep-Away on top of. In its absence, you should be able to just keep spinning events forward through a combination of your faction progressions and responding to the PCs’ actions.

The first issue of Zot! for example, could be framed as the GM triggering the following progressions / faction features:

- THIEF: Attempts to use an interdimensional portal to hide the Key on Our Earth.

- SIRIUS IV: Successfully tracks the Key [locating it on Our Earth] and dispatches a robot kill squad to its location.

- [At this point, the PCs – who have been keeping an eye on the Sirius IV faction – track the robot kill squad to Our Earth and destroy it. They also find the Key and choose to turn it over to the proper authorities in the form of the CPZP.]

- THIEF: Checks his hiding place. [Finding the Key missing, he tracks it.]

- THIEF: Uses a stealthed robot to steal the Key.

- DE-EVOLUTIONARIES: Track the Key and brazenly attack [the CPZP council meeting].

- [The PCs fail to detect the Key being stolen and fight a big battle with the De-Evoluationaries.]

The linear nature of this, mirroring the structure of the original story, may be deceptive. So consider how the GM can trigger the exact same progressions but end up with a completely different result based on the actions of the PCs:

- THIEF: Attempts to use an interdimensional portal to hide the Key on Our Earth.

- SIRIUS IV: Successfully tracks the Key [locating it on Our Earth] and dispatches a robot kill squad to its location.

- [At this point, the PCs – who have been keeping an eye on the Sirius IV faction – track the robot kill squad to Our Earth. They fight, but lose. The robot kill squad captures the Key, but the PCs aren’t aware of this fact. The PCs regroup and pursue the robot kill squad.]

- THIEF: Checks his hiding place. [Finding the Key missing, he tracks it.]

- [PCs arrive back at the home base of the robot kill squad and continue their surveillance. The Sirius IV faction leaders, learning that the robot squad has secured the key, board a shuttle and begin flying towards the compound.]

- THIEF: Uses a stealthed robot to steal the Key.

- [PCs don’t spot the thief’s robot sneaking into the Sirius IV compound.]

- DE-EVOLUTIONARIES: Track the Key and brazenly attack [the Sirius IV robot compound].

- [The PCs notice the stealthed robot sneaking back out of the compound in the chaos. They attack that robot as the Sirius IV shuttle arrives onsite. The Sirius IV representatives spot the PCs, but are ambushed by De-Evolutionaries as they move to intercept. The PCs destroy the thief’s robot and take the key back. Taking the ruined remnants of the robot back to Zot’s Uncle Max, they use it to identify the thief.]

In actual play, what you’ll generally end up with is a cluster of raid (when the PCs go to steal the McGuffin) and siege (when the PCs have the item and need to protect it) scenarios. The more the factions interact with each other, the more crazed these scenarios will become.

BEYOND THE DOORWAY

Our use of the Maltese Falcon in our hypothetical scenario already points the way towards the Dashiell Hammet novel and John Ford movie as another example of this scenario structure in other media. As with Zot!, the scenario begins with the McGuffin already in keep-away mode. (You could also interpret that back story of The Maltese Falcon – with various treasure seekers attempting to trace the Falcon’s trail – as a Race to the Prize scenario, the conclusion of which then bounces directly into a McGuffin Keep-Away scenario).

Another Humphrey Bogart film to consider is Casablanca, in which the letters of transit function as the McGuffin. The thing to note here is that even though the McGuffin DOESN’T change hands repeatedly, the narrative remains interesting. So don’t feel as if you need to force the item to bounce around amongst your various factions: It’s perfectly okay if it settles into the hands of the PCs (or some other faction). As other factions come to barter with (or threaten) the controlling party, the drama will continue to flow.

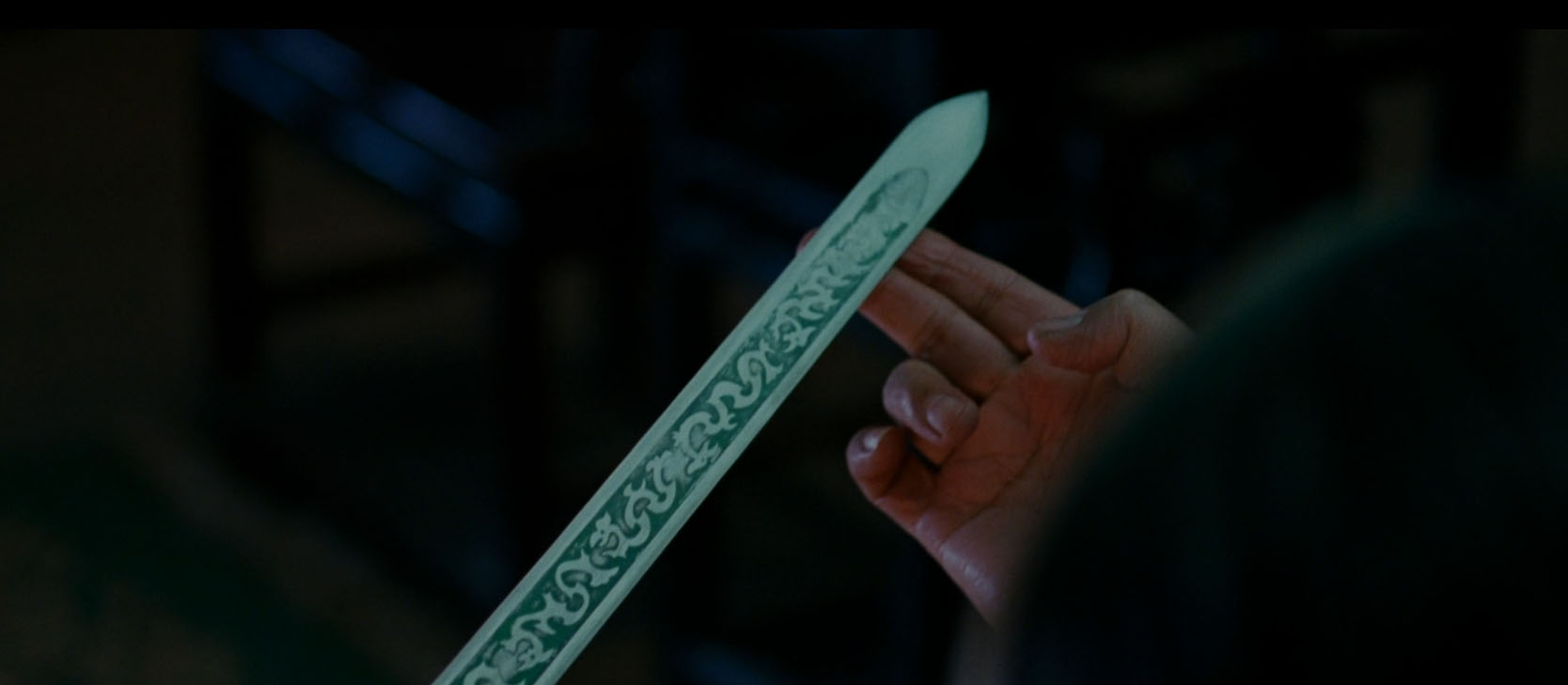

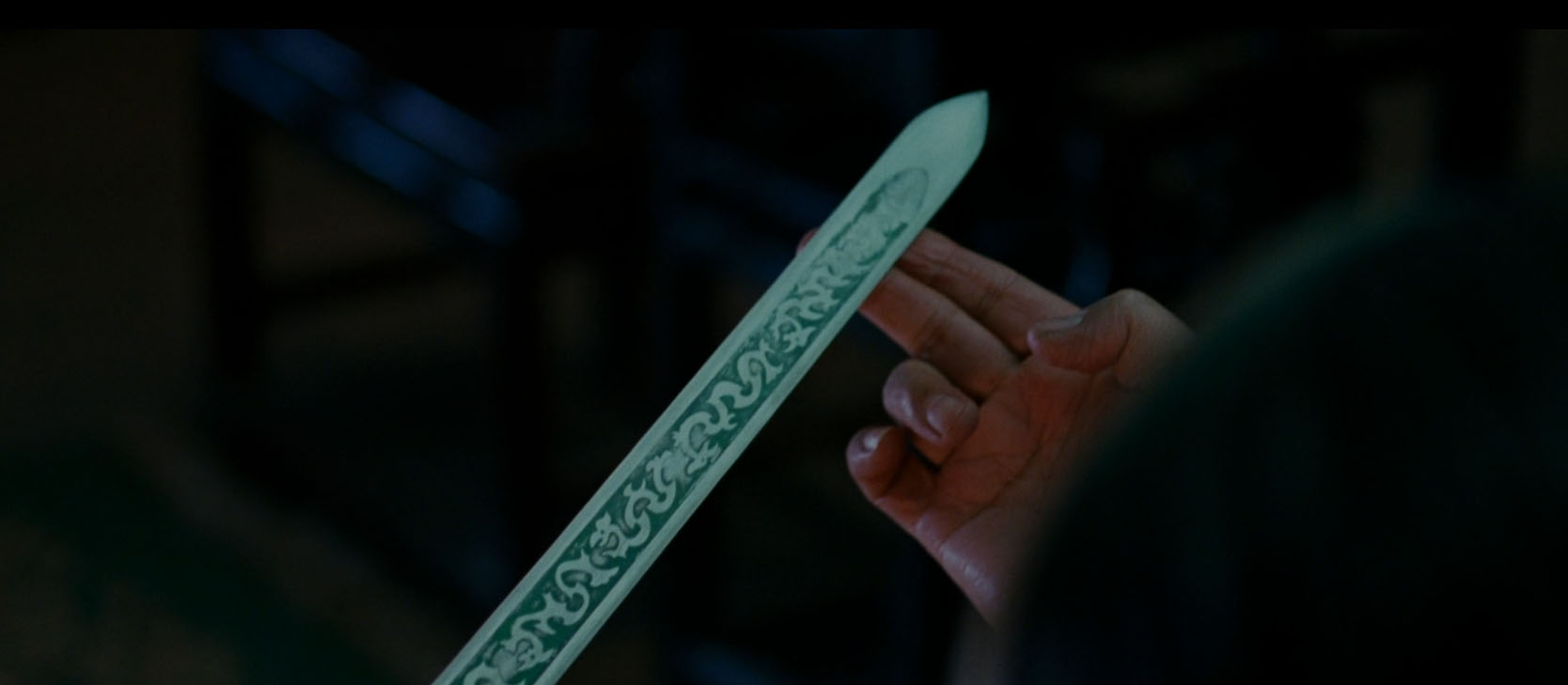

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon is an interesting example to break down. There are fewer factions, but a larger number of rogue agents pursuing independent goals within the arena defined by the McGuffin Keep-Away. Consider, too, that the McGuffin in this case – the Green Destiny sword – has a specific utility which is useful for the keep-away itself. This not only creates an interesting transition of advantage as the McGuffin bounces around, but also encourages the faction currently controlling the item to use it, often creating large, clear paths for the other factions to follow.

Go to Challenge #4