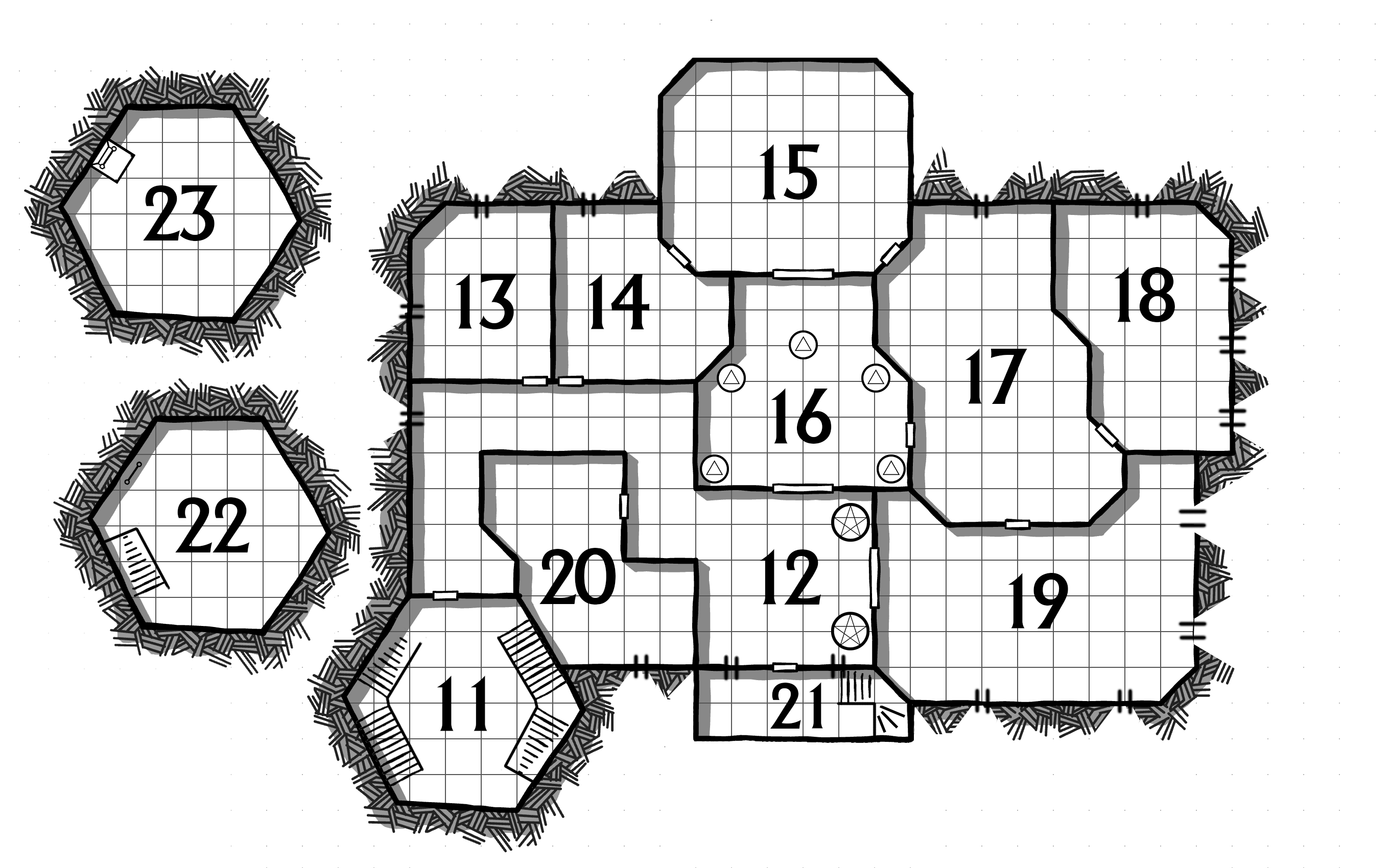

AREA 11 – LANDING

Stairs curve up and down from this landing. Upon a wooden perch next to the staircase leading up, a clockwork raven sits.

CLOCKWORK RAVEN: Obsidian feathers and ruby eyes. It will turn its head to follow motion and cry out, “Who goes there?” if someone approaches the staircase leading up, but it’s a simple mechanical oddity. It cannot fly nor think.

AREA 12 – UPPER HALL

Two suits of decorative armor bearing the Vladaam heraldic crest on their chests stand at one end of this hall, flanking a door.

GM Background: These suits of animated armor (helmed horror, MM 2024, p. 166) used to stand at the Front Entrance where the pearl golems now stand. They were created several decades ago by Flambara of Ossyr when the Company of Red Magi was first founded, but their magic has severely decayed. They’ll falsely challenge even legitimate members of the guild, but can be easily be talked out of their challenges.

GM Background: These suits of animated armor (helmed horror, MM 2024, p. 166) used to stand at the Front Entrance where the pearl golems now stand. They were created several decades ago by Flambara of Ossyr when the Company of Red Magi was first founded, but their magic has severely decayed. They’ll falsely challenge even legitimate members of the guild, but can be easily be talked out of their challenges.

AREA 13 – ARCHMAGE CRETAI

A blue rug with arcane sigils stitched into it with silver thread fills the floor between a bookcase, a worktable of alchemical equipment, and a comfortable bed.

MEDUSA OF THE RINGS: On the worktable, almost directly opposite the door, there is a porcelain bust of a medusa’s ehad. The porcelain snakes framing her face are animate – writhing and twisting to look at anyone in the room.

- Rings: Eight of the snakes have beautifully crafted rings threaded onto them. Four are magical: ring of climbing, ring of jumping, ring of protection, ring of sustenance. Four are nonmagical, but very beautiful: a fire opal carved to resemble a basilisk (460 gp); a ring of jagged orange quartz (10 gp); a ring of black metal set with three opals (150 gp); a ring of goldleaf wood (2,500 gp; a pale ivory laced with veins that glitter like gold).

WORKTABLE: Cretai has a pair of goggles of minute seeing. He is attempting to modify the goggles alchemically to produce goggles of true seeing (without needing the arcane puissance to cast a true seeing spell), but his efforts have so far come to naught.

- A Guidance from Renn Sadar to the Archmage Cretai

- DM Background: Cretai acts as an agent for Renn Sadar (Ptolus, p. XX). Sadar funnels research abandoned by the Inverted Pyramid as being too dark or too dangerous to the Red Company of Magi through Cretai; Cretai sees to it that the secrets of the Red Company (and also the Vladaams) are fed back to Renn Sadar.

BOOKCASE: Contains lore concerning the Ethereal Plane. Offers a +4 bonus to any related Intelligence checks.

- Search – DC 14 Intelligence (Investigation): To find an everfull purse hidden in a hollow book.

Ring of Climbing (Uncommon): This ring grants the wearer a climbing speed equal to their normal speed.

Everfull Purse (Rare): This leather belt pouch has the power turn a single gold coin into many overnight. If a single gold piece is placed in the everfull purse at sunset, it will be replaced at sunrise by 25 gold pieces. The purse has no effect if more than one gold piece is left within, or if anything other than gold is placed with in.

AREA 14 – ARCHMAGE VERACK

This room is dominated by a luxurious red-and-gold rug depicting two dragons chasing each others’ tails in orbit around a blazing sunburst. Bookshelves line one wall of the room and a writing desk is positioned under the window.

BOOKS: A detailed and esoteric collection of dragon lore, notably including Lore of the Wyrmhoards in the Mountains of the East, granting advantage to any appropriate knowledge-based Intelligence checks.

WRITING DESK: Empty except for some blank sheets of paper and well-stoppered vials of ink. In one drawer there is a polished silver mirror with a single large crack running through it; the crack is blackened as if it had been caused by an intense flame, but the rest of the mirror is unharmed.

- DC 16 Intelligence (Arcana): This sort of mirror is used for scrying

- DC 22 Intelligence (Arcana): This sort of damage would be caused by a scrying spell encountering an overwhelming defense against scrying or an intense source of power.

SEARCH – DC 10 Intelligence (Investigate): There’s a definite layer of dust, a staleness to the sheets, and a general sense of disuse about the room. No one has been living in this room for at least several weeks.

SEARCH – DC 20 Intelligence (Investigate): There’s a hidden compartment under the rug containing:

- +1 dragon rifle

- mithril shirt

- scroll of ray of enfeeblement

- scroll of finger of death

- scroll of shocking grasp

- longsword in a scabbard of black leather with a dragon head of copper at its tip (see below)

SCABBARD – DC 10 Intelligence (Investigate) / DC 24 Wisdom (Perception): The scabbard is longer than the sword it holds. The tip is false and contains a ring of dragonform.

Ring of Dragonform (Rare): Fashioned from copper, this full finger ring is fashioned like a dragon’s claw. Once per day, the wearer may use an action to transform into either a young copper dragon (if the wearer is good) or young red dragon (if the wearer is evil). (A neutral wearer may choose which dragon form they are most akin to, but thereafter can only choose that form when using the ring.) This effect functions as a true polymorph spell.

GM Background: Verack is currently in the Imperial capital city of Trolone engaged in various arcane research.

AREA 15 – BALCONY

The doors from this balcony are arcane locked and have alarms on them (mental alarm, triggered to either Guildmaster Arzan or, for the door to Area 14, the Archmage Verack).

Note: This means that opening the door to Area 14 will effectively NOT trigger an alarm because Verack is too far away to receive it.

AREA 16 – ALIASTER’S SCULPTURES

Glass doors look out onto the balcony (Area 15), in addition to the double doors of oak leading to Area 12 and the small side door to the Apprentice Laboratory (Area 17). There are five pieces of sculpture on marble plinths located around the perimeter of the hall.

BALCONY DOORS: These doors are arcane locked and has an alarm on them (mental alarm, triggered to Guildmaster Arzan).

SCULPTURES: Each sculpture is marked with Aliaster’s arcane sigil. One of the sculptures is signed with the name “Aliaster.” (All of these sculptures were, of course, created by Aliaster Vladaam.)

Aliaster’s Arcane Sigil

SCULPTURE 1: A beautiful, nude maiden has been half exposed from an unfinished chunk of marble which is still half unhewn and rough. Her hair, which hangs down over her face (obscuring her visage entirely), is of elfin gold (flexible and pliant) and possessed of an enchantment which causes it to stir slightly as if caught in the breeze.

Every few minutes, the “breeze” picks up, causing the hair to sweep aside and reveal – for only the briefest of moments – the hideous, demonic, skull-like visage of the maiden’s face.

SCULPTURE 2: A massive, muscular arm thrusts up from the surface of the plinth. If anyone draws near, the arm will reach out plaintively towards them.

SCULPTURE 3: A simple bust of white stone, depicting the thoughtful visage of a beautiful woman. The plinth is labeled “Flambara, the Eternal Flame of My Heart.” (Use Philippe Faraut’s Guardian as a visual reference.)

SCULPTURE 4: Another simple bust of white stone, this one labeled “Nulara Aretari.” (Use Philippe Faraut’s Child of Senegal for visual reference.)

SCULPTURE 5: A sculpture of an ent sitting upon a rotting log, looking down in enigmatic thought upon the splayed body of a dead dryad. The ent’s leaves are enchanted so that they sway gently in an unseen wind.

AREA 17 – APPRENTICE LABORATORY

Multiple tables filled with a chaotic assortment of equipment and tools fill the walls and center of this room.

APPRENTICE WORK: The apprentices are currently being instructed on feather tokens. There is a completed anchor feather token and partially finished anchor feather token, bird feather token, and whip feather token.

There’s approximately 4,000 gp worth of miscellaneous equipment. Of particular note are two vials of universal solvent.

DM Background: This laboratory is used by the Vladaam Mages and Researchers. The Archmages and Guildmaster instruct them here or them crank out minor magical items according to the Guild’s needs.

AREA 18 – ARCHMAGES IMOGEN & ALDWYCK

A utilitarian chamber with two modest beds against opposite walls, flanking a pair of matching worktables. Next to one of the worktables is the partially constructed form of an iron statue. Its head lies on the table next to it.

FIRST WORKTABLE – IRON STATUE: This is actually a partially completed iron golem. Aldwyck is attempting to complete it in order to impress the other Archmages, but he’s bitten off more than he’s actually capable of.

- Iron Head: The head will blink and turn to look at anyone approaching the table. It will attempt to form words, but can say nothing.

- On the Table: An incomplete iron golem manual. It includes a copy of the cloudkill spell and would have a market value of 6,000 gp.

SECOND WORKTABLE: A +2 battleaxe of dwarven make lies on the table. The enchantments on it, however, have been dissected and splayed out using ethereal pinions – glowing beams of blue energy stretch tautly between the pinions and the waraxe.

- Removing Pinions: Removing the pinions without disrupting the axe’s enchantments requires a DC 25 Intelligence (Arcana) check. Proficiency with Smith’s Tools grants a +5 bonus on this check. On a failure, the battleaxe is destroyed (rendering it a mundane weapon). Tool proficiency

- Battleaxe: The battleaxe originates from the forges of Dwarvenhearth.

SEARCH – DC 12 Intelligence (Investigation): There’s a polished silver mirror worth 1,000 gp under the pillows on one of the beds.

- DC 18 Intelligence (Arcana): This is a scrying

DM Background: Imogen and Aldwyck are lovers. They are also the two newest archmages among the Red Magi.

AREA 19 – APPRENTICE BUNKS & DINING HALL

This room serves as basically a boarding house for all of the Vladaam Mages and Vladaam Researchers in the guild.

The walls of this chamber are lined with bunk beds that are four high. A large table and rickety-looking chairs fill the middle of the room. The table is covered in dirty dishes in various phases of filth and vaguely organic growth.

BUNK BEDS: A total of twenty-four berths in six stacks of four-high bunk beds.

TREASURE: Secreted under mattresses, lying around on small side tables, kicked into a corner.

- large steel shield +1

- a fancy cloak of silver wolf fur (110 gp)

- ivory and silver carving service (310 gp)

- ornamental silver inkpot with blue quartz gems (100 gp)

- silver locket with platinum filigree depicting a rose (90 gp)

- pouch containing 199 pp

- potion of levitate (cursed; the possessor must eat twice as much as normal for a fortnight)

- a violet spinel (600 gp)

AREA 20 – LIBRARY & ARCANE CIRCLE

The library is well-stocked with arcane lore. Studies in this library benefit from a +2 bonus to Intelligence (Arcana) checks.

BOOKS: In addition to a copy of Hate of the Cobra, the library contains copies of the following chaos lorebooks:

- Lore of the Demon Court

- Mouth of the Void

- The Writhing Obelisk

- The Earthbound Demons

- The Magi of Chaos

- Book of the Elder Brood: Akop

ARCANE CIRCLE: Spells cast within the arcane circle are treated as if they had been cast with a spell slot one level higher than the one used by their caster.

AREA 21 – REAR BALCONY

This area is surprisingly poorly guarded.

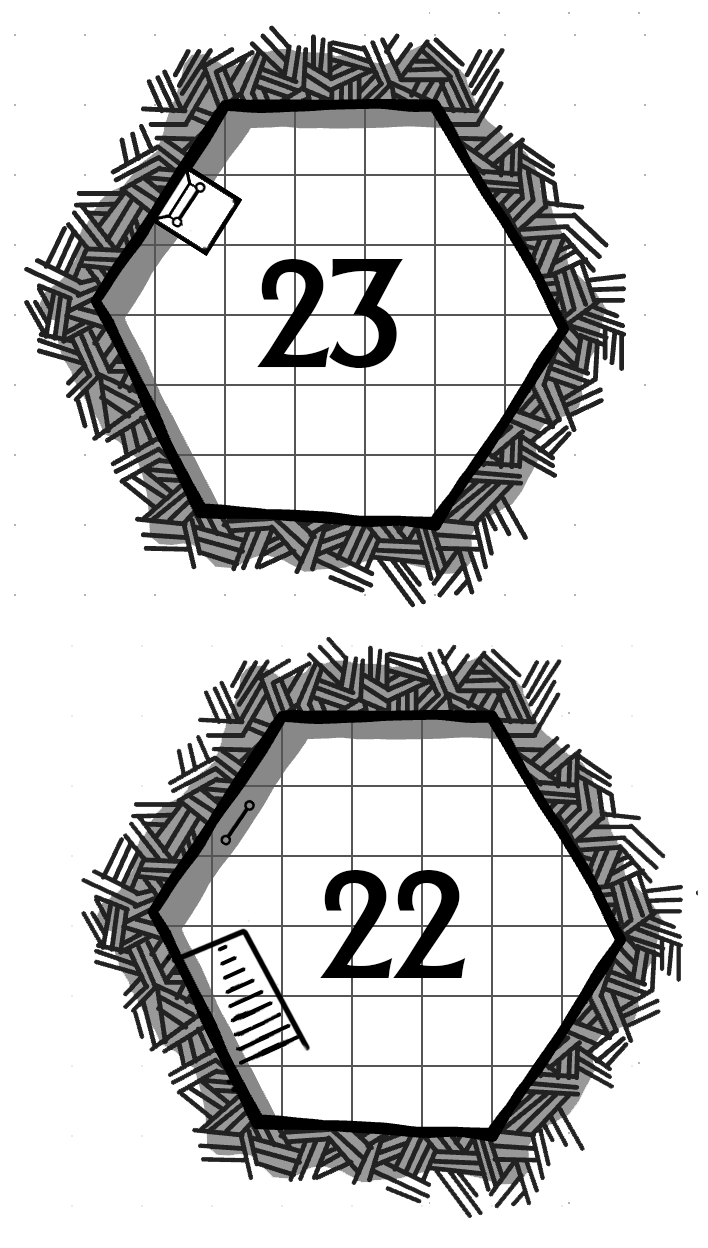

AREA 22 – ARCHMAGE TIANT

This room dances to the tune of the many multi-colored magical flames which fill it: A huge pit of blue fire that shifts to purple and then to red and then to yellow and back around again fills the center of the chamber. Candle-less candelabras jut out from the wall, while other flames go cavorting around and through the jumbled cascade of magicl equipment, books, and haphazard worktables.

IRON LADDER: Leads up to a trapdoor in the ceiling about 20 feet up.

IRON LADDER: Leads up to a trapdoor in the ceiling about 20 feet up.

WORKTABLES – DC 20 Wisdom (Perception): To notice that the top of one of the worktables has a concealed key hole (DC 22 Dexterity (thieves’ tools)). If unlocked, the tabletop can be lifted to reveal a hidden storage chamber containing:

- Liquid Pain (12 doses) and Letter from Gattara to Tiant

- GM Background: Tiant and Gattara are occasional lovers.

WORKTABLE – DC 20 Intelligence (Arcana): To recognize that Tiant is currently creating a staff of fire. Unusually, he appears to be hollowing out the core of the staff and inscribing it with alchemical sigils linked by arcane runes.

- GM Background: Tiant plans to fill the hollow core of the staff of fire with liquid pain, resulting in a the spells inside the staff being cast with a +2 spell slot level.

SEARCH – DC 18 Intelligence (Investigation): To detect a section of the wall brimming with magical potential. Pressing firmly against this magical potential causes a section of the wall to transform into a large, comfortable bed. Pressing the wall above the bed’s headboard causes the bed to re-merge with the wall.

AREA 23 – TOWER ROOF

A large apparatus of contorted metal and brass tubing has been erected on the roof.

APPARATUS – DC 15 Intelligence (Arcana): This is an etheric monitoring device. It maintains a connection with the Ethereal Plane and can be used to peer or scry into that plane.

AREA 24 – BASEMENT

A mummified corpse has been shackled to a wooden table in the corner of the basement. The rest of the room is piled high with an assortment of junk.

JUNK:

JUNK:

- a chest with a broken lid

- decayed clothing

- a jar of dead flies

- an alchemist’s kit (useless from age)

- a small ivory figurine that has been defaced past recognition

- wicker baskets with ripped out bottoms

MUMMY: The mummified corpse, however, is an actual mummy. Once part of some experiment, it was secured and then discarded down here with the rest of the junk.