When the D&D 3rd Edition Player’s Handbook was released at Gen Con 2000, two third-party modules were available the same day on the convention floor: Atlas Games’ Three Days to Kill by John Tynes and Green Ronin’s Death in Freeport by Chris Pramas. The first official D&D module for 3rd Edition, The Sunless Citadel by Bruce Cordell, wouldn’t be released until September 2000. This might seem totally unremarkable today, but that’s only a testament to how truly revolutionary the moment was at the time. This was the birth of the OGL, and the hobby and industry would never be the same again.

I was and am a big fan of all three of these modules. When I launched my first D&D 3rd Edition campaign, I used Three Days to Kill and used the end of that adventure to plant a hook that would lead the PCs to The Sunless Citadel. (My second 3rd Edition campaign would start with Death in Freeport.)

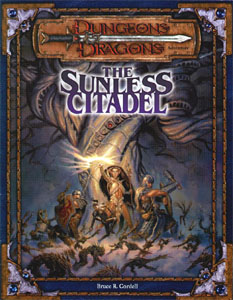

At this time, I was prepping mix-tape soundtracks for every adventure that I ran, with tracks cued to specific locations, characters, events, and scenes. I would also often take these soundtracks, burn them to CD, create cover art, and give them to the players as mementos. (You can see the CD cases for the Sunless Citadel soundtrack above.)

I’ve previously shared one of the soundtracks from my D&D adventure The Fifth Sepulcher. As I was recently prepping my review of The Sunless Citadel, I revisited my notes for the adventure, found the original soundtrack listing I’d used, and thought it might be fun to share it here. It can be just as easily used with the 5th Edition version of the adventure, which was published in Tales from the Yawning Portal.

SUNLESS CITADEL – SOUNDTRACK

Oakhill

1. The Journey North (Final Fantasy IV, Track 7, Main Theme)

2. Avenue of Stone (Princess Mononoke – Japanese Soundtrack, Track 1)

3. The Villagers (Ancient Airs & Dances, Track 4, L’usignuolo)

4. Oakhill (Ancient Airs & Dances, Track 8, Villanella)

5. To the Citadel (Final Fantasy IV, Track 33, Somewhere in the World)

The Sunless Citadel

6. Song of the Citadel (Final Fantasy VIII, Track 2-7, Galbadia Garden)

7. The Threatened Halls (Final Fantasy IX Plus, Track 13)

8. Haunted Ways (Final Fantasy VIII, Track 3-14, The Salt Flats)

9. Shadows of Suspense (Lost in Space, Track 13, The Proteus)

10. The Eldest Halls (Planets – Holst, Track 5, Saturn – The Bringer of Old Age)

Combat

11. The Thrill of Blades (Final Fantasy IX Plus, Track 3) – set-up to fast pace

12. The Goblin Drums (Final Fantasy VIII, Track 1-9, Starting Up) – thrilling to steady pace

13. Race to Perdition (Final Fantasy VIII, Track 2-5, Only a Plan Between One and Perdition)

14. A Suspended Breath (Princess Mononoke – Japanese Soundtrack, Track 2) – suspense to combat

The Dark Grove

15. The Greeting of Belak (Final Fantasy VIII, Track 2-6, Succession of Witches)

16. The Temptation of Belak (Final Fantasy VIII, Track 1-8, The Landing) – 50 seconds to combat, segue to Track 17

17. The Death of Belak (Final Fantasy VIII, Track 2-12, Fithos Lusec Wecos Vinosec)

18. The Blackened Trees (Final Fantasy VIII, Track 1-6, Find Your Way)

19. The Dark Grove (Princess Mononoke – Japanese Soundtrack, Track 6)

20. The Cavern of Stars (Universal Sampler ’92, Track 8, And Evening Falls)

21. The First Seal (Final Fantasy VIII, Track 3-4, Blue Sky)

SOUNDTRACK GUIDE – CAMPAIGN TRACKS

There are a couple of places where this soundtrack reflects how I homebrewed The Sunless Citadel to it into my ongoing campaign, so let’s take a peek at those first.

Track 1 – The Journey North: As I mentioned above, I started the campaign with Three Days to Kill. The PCs headed north to reach Oakhill and the Sunless Citadel, and this was the soundtrack for that.

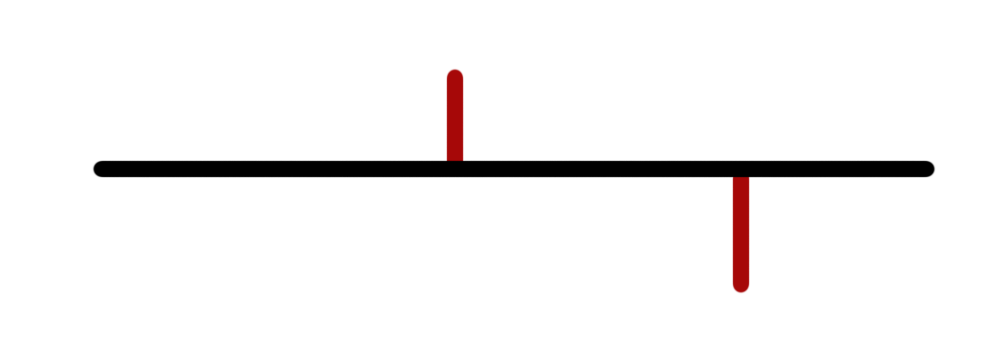

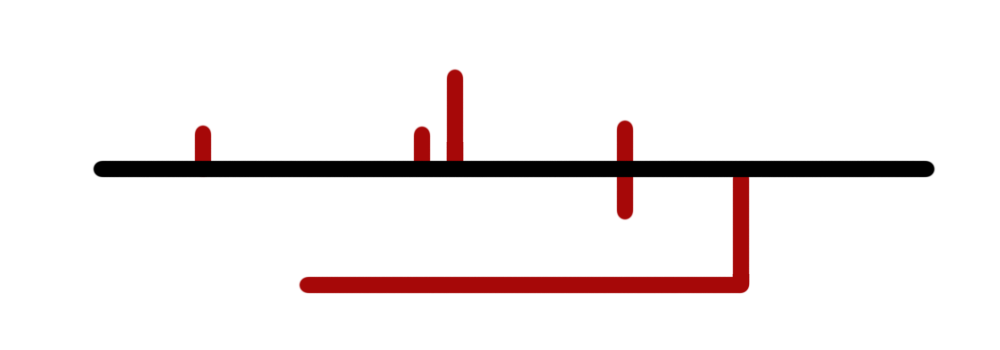

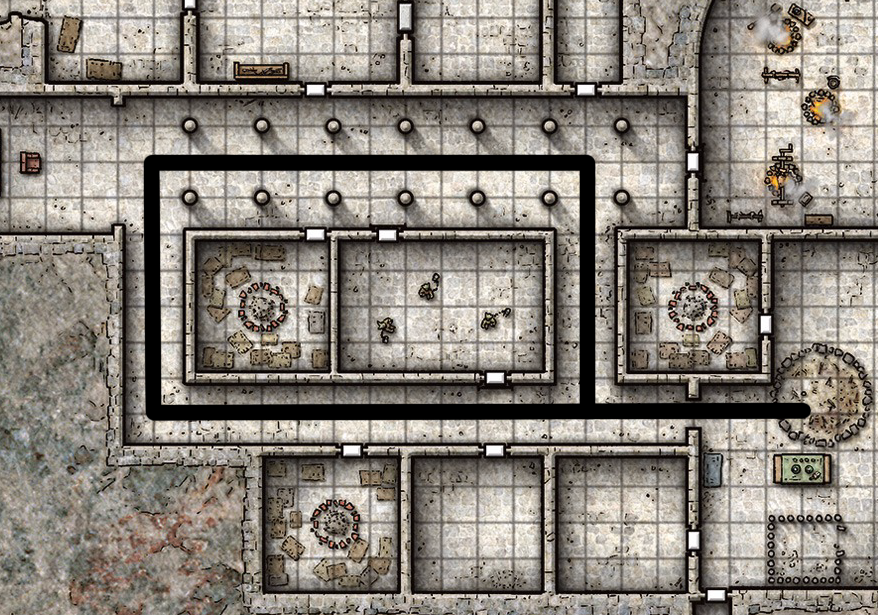

Track 2 – Avenue of Stone: I placed the village of Oakhill, where The Sunless Citadel begins, in a section of my campaign world that had once been ruled by an Elven empire. (The Citadel was also lightly themed to support this and reveal some of the secret history of this Elvish civilization.) Taking inspiration from Avebury, I embedded the village in druidic circles, including a mystically preserved wood circle (known as an ilda circle):

As you emerge from the far end of the tunnel, you find yourself standing just a few short feet away from two large blocks of wood – nearly four meters tall and half as wide – on either side of the road. It takes you a moment to realize that fourteen others just like them stand in a circle. Each is inscribed with runes which seem to glow a faint blue in the waning sunlight.

The road passes through the center of the circle, and continues on beyond it.

Then, as at ancient Avebury, an avenue of stone led to Oakhill, and then another from Oakhill to the Citadel:

The Unen’dil runs for nearly three miles before its stones begin to decrease in size. The avenue of stone is abruptly interrupted by a natural ravine. At the point where the ravine actually intercepts the road, it more closely resembles a deep, but narrow, canyon. Beyond this ravine you can see a few more of the smaller standing stones of the Ulen’dil, but you notice that – on that side of the ravine – the stones seem to be suffering the weathering of great age. The road also continues, but – like the South Road you came in on – the North Road loses its ancient precision beyond the boundary of the standing stones.

Several broken posts stand on either side of the ravine. It appears that a bridge of some sort once reached across the gap in the road here, but it has collapsed. The ravine itself runs out of sight in an east-west direction.

So this track was picked to set the mood for this ancient history.

Track 21 – The First Seal: The campaign arc involving the PCs finding and sealing three ancient seals that had been damaged as a result of their actions during Three Days to Kill. The hook for The Sunless Citadel was that one of these seals was located within the Citadel, so this track is the grand finale.

SOUNDTRACK GUIDE

Oakhill

Tracks 1 & 2: See above.

Tracks 3 & 4: These are, obviously, for the PCs’ arrival and interaction in Oakhill.

Track 5 – To the Citadel: Track title says it all.

The Sunless Citadel

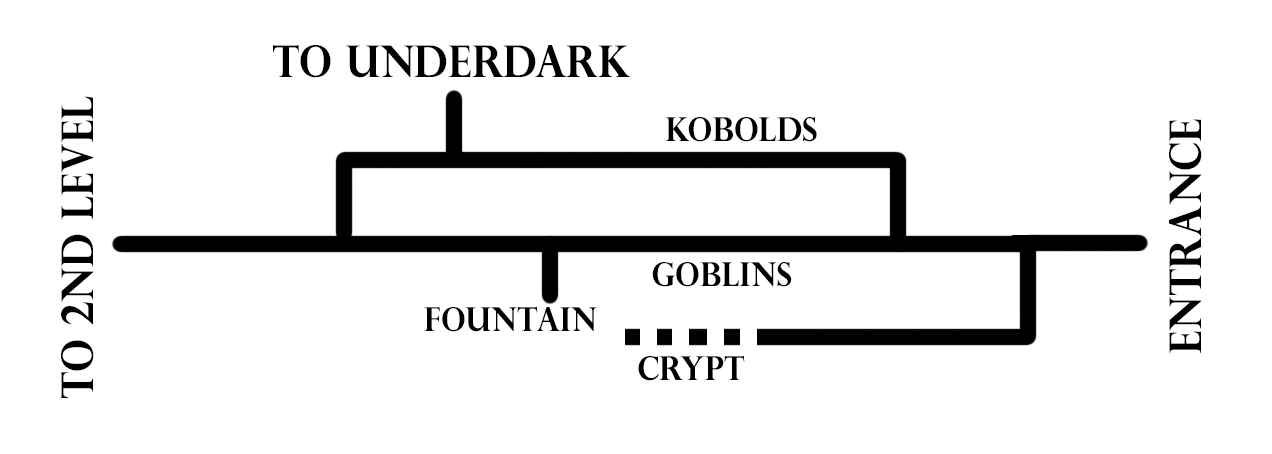

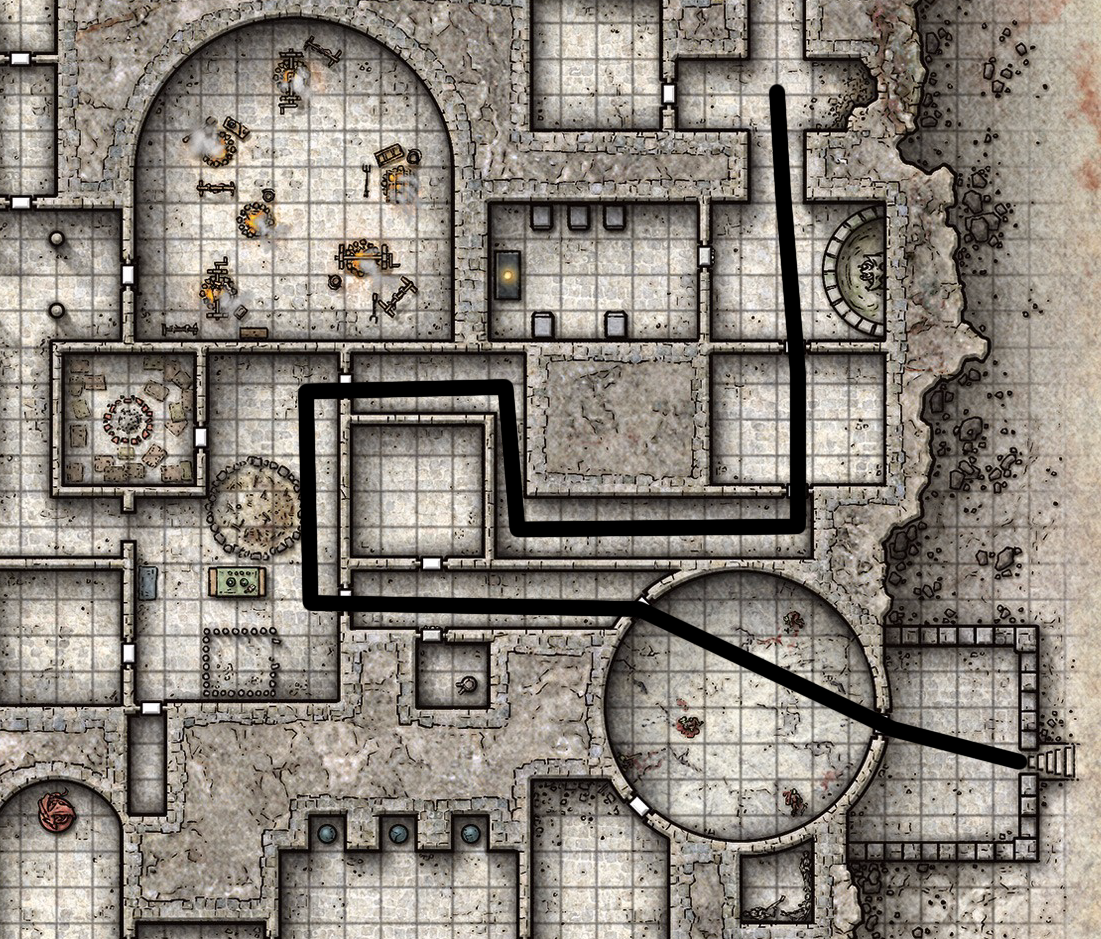

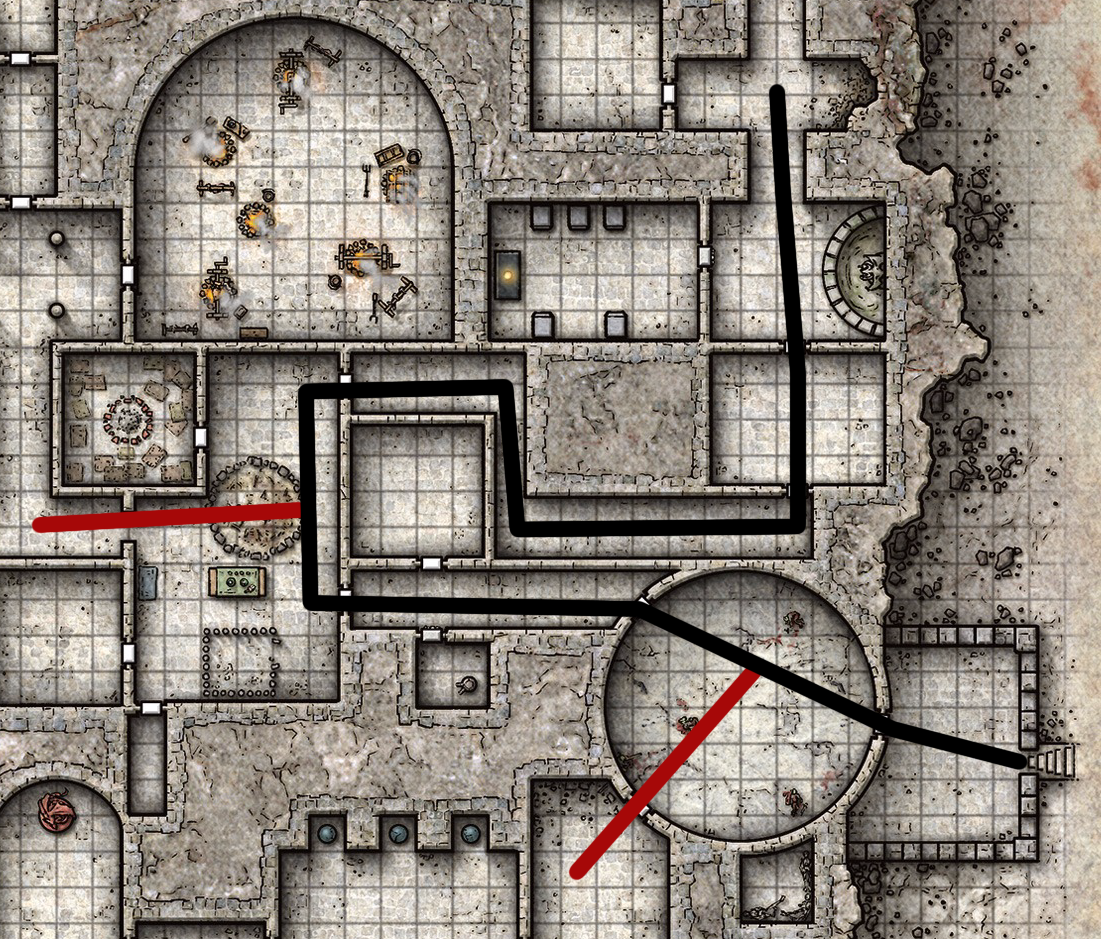

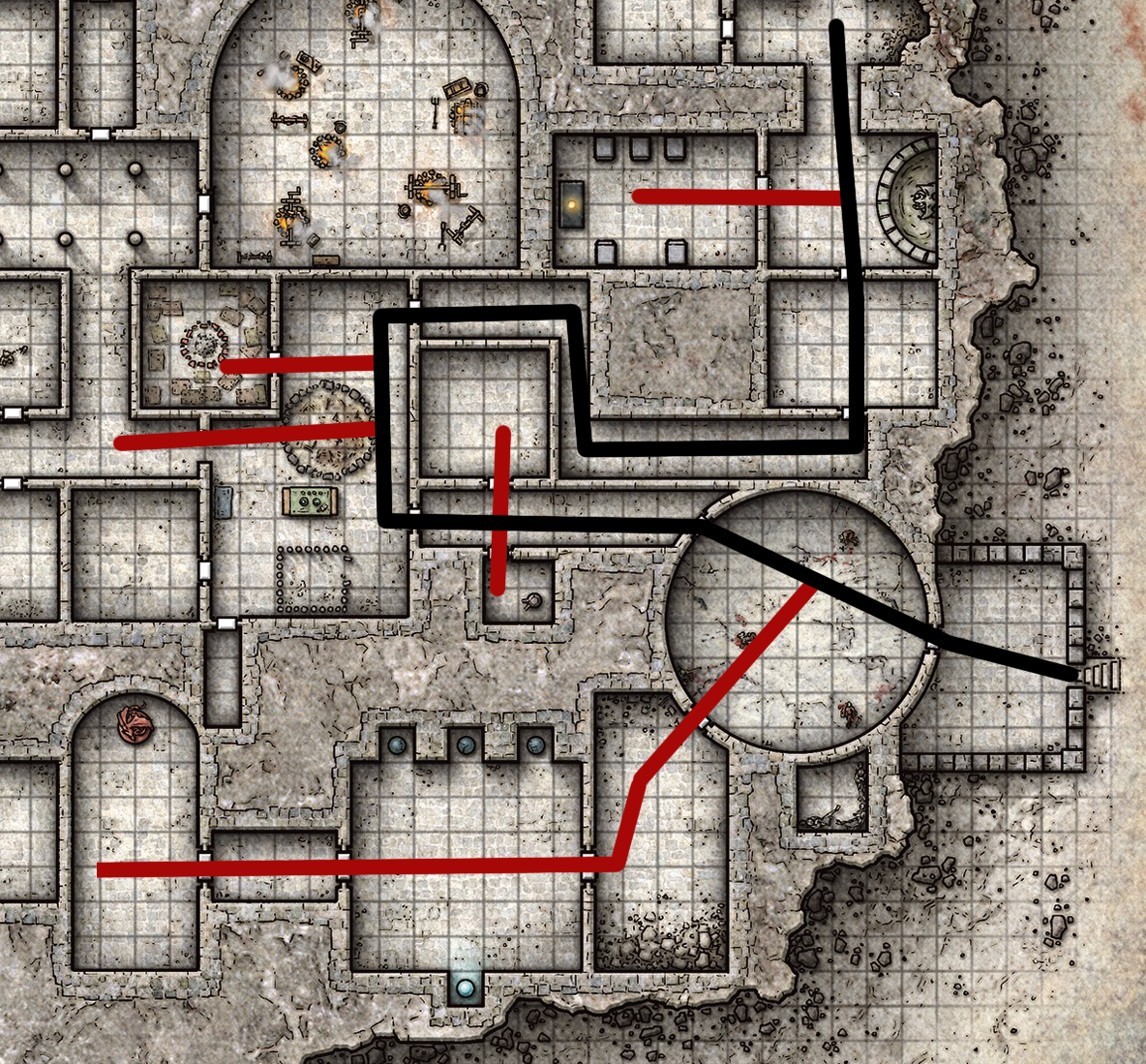

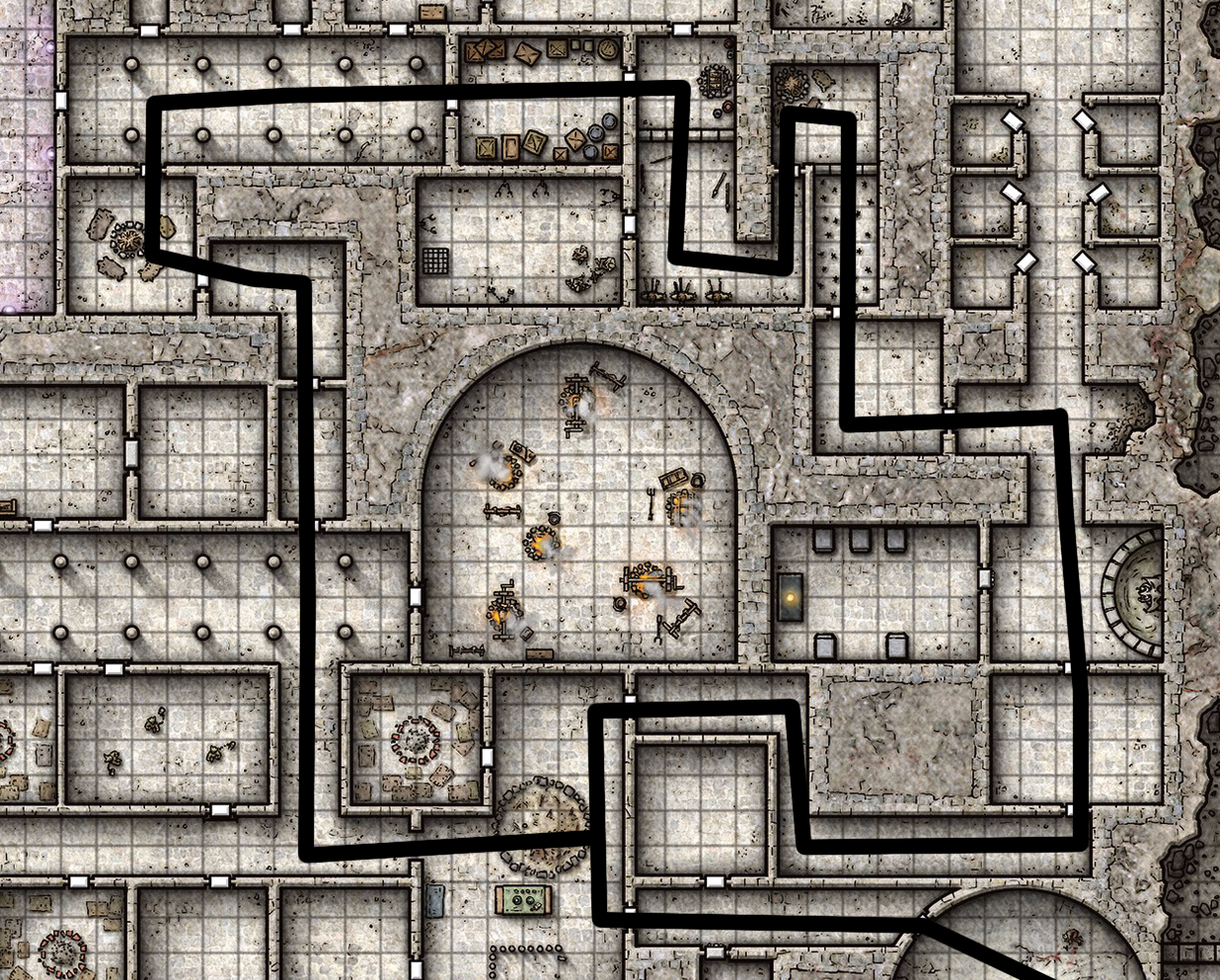

Track 6 – Song of the Citadel: This was intended to be the default background music for the Citadel. I used it as the PCs entered the Citadel for the first time, and then I’d loop back to this track out of the other Sunless Citadel/Combat tracks. It was really too short for that, but using it as a transition between other pieces helped with that a bit.

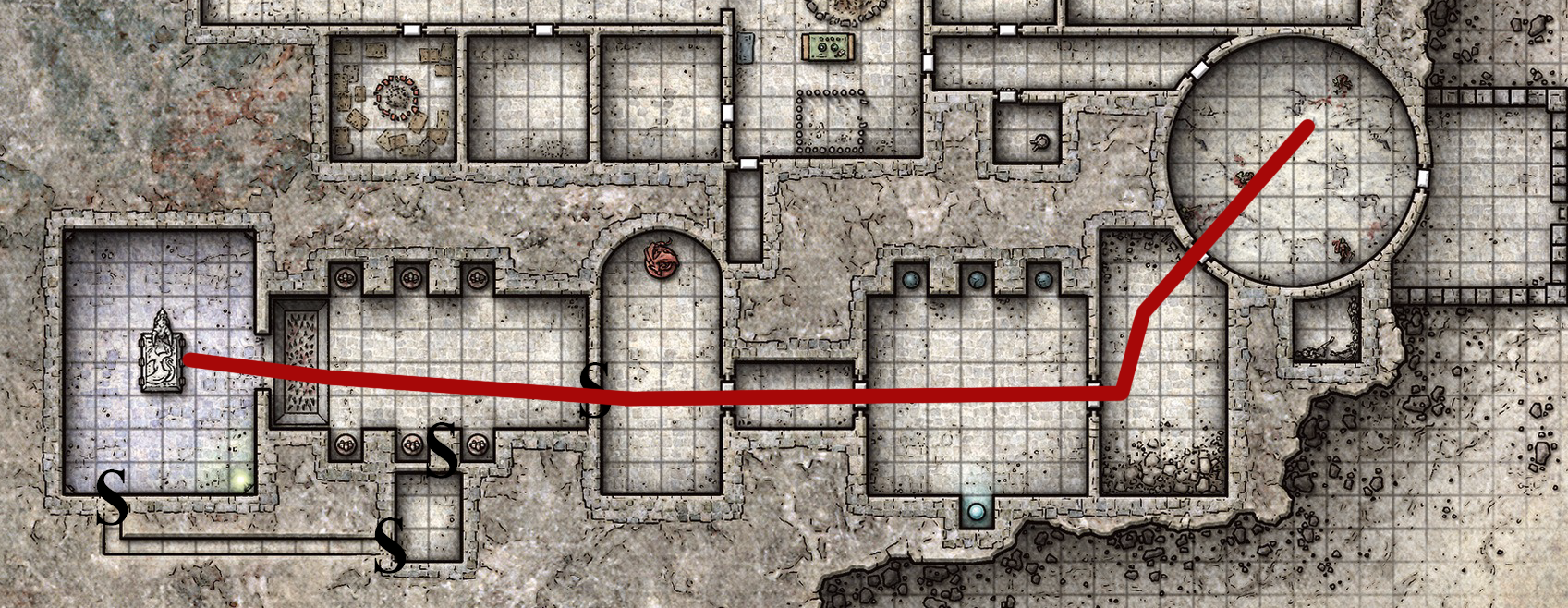

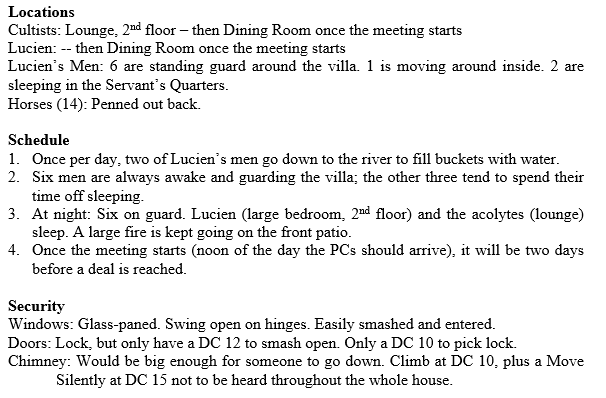

Track 7 – The Threatened Halls: Used for kobold areas.

Track 8 – Haunted Ways: Areas 28, 29, and 30.

Track 9 – Shadows of Suspense: Used for goblin areas.

Track 10 – The Eldest Halls: Area 20

Combat

These were, obviously, used for various combat scenes. They were lightly themed to different opponents (e.g., “The Goblin Drums” was my default for kicking off goblin fights), although I would also swap between tracks to keep things fresh.

You can also see that I notated the track list to indicate the pace/tone/structure of the track. This would help me in sort of “live mixing” the music. (For example, if we reached a suspenseful moment in a fight — maybe somebody was making a vital saving throw! — that might be a good time to swap to “A Suspended Breath – suspense to combat.”)

The Dark Grove

These tracks were keyed to the lower level of the Sunless Citadel.

Tracks 15, 16, 17: These tracks scored the final meeting (and probably fight) with Belak, the dark lord of the Sunless Citadel.

Track 18 – The Blackened Trees: This was the default background track for the lower levels.

Track 19 – The Dark Grove: Areas 49, 54, 56

Track 20 – Cavern of Stars: Area 55

FURTHER READING

Music in Roleplaying Games