Our first scenario structure challenge is the Death Star sequence from the original Star Wars. More generally, this is an exemplar of a “space station infiltration” mission, but we’ll be using the Death Star as a useful parallel (while acknowledging the limitations of this).

What makes the Death Star scenario tick?

(I’m just going to assume here that everyone is familiar with Star Wars. If you’re not familiar with it, do yourself a favor and immediately track down a copy of the original, unaltered version and watch it ASAP.)

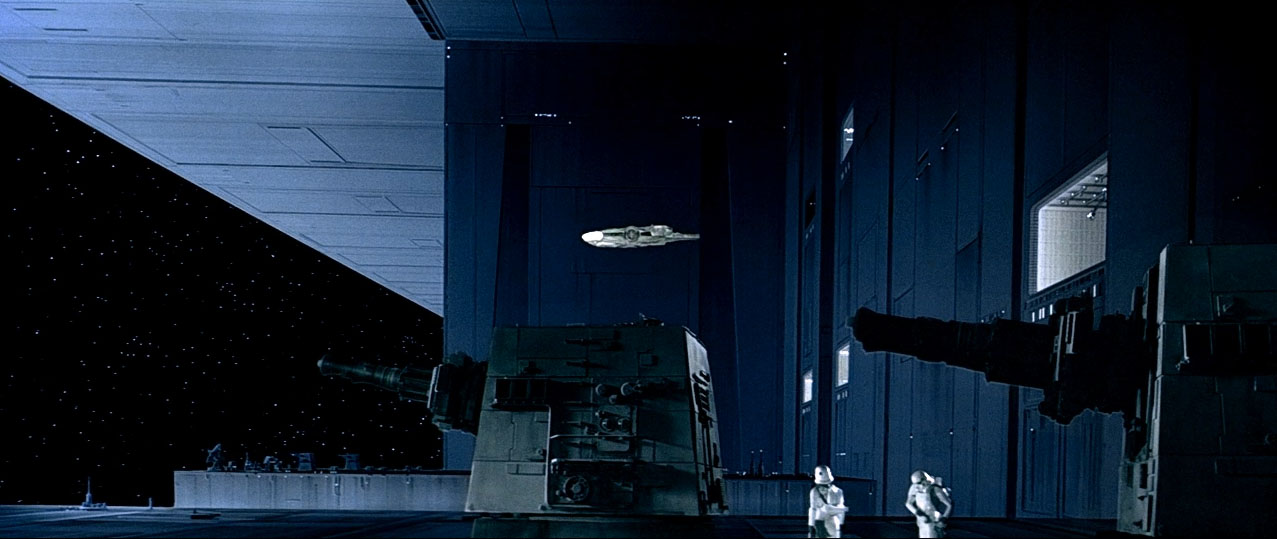

- The PCs have to gain access to the Death Star. (In the case of the movie, they got captured by its tractor beam and hid in the smugglers’ compartments.)

- There was a primary obstacle they had to overcome in order to get out. (The tractor beam needed to be disabled.)

- There was an objective they wanted to accomplish. (Rescue the princess.)

- There was a grab bag of situational obstacles that needed to be overcome, bypassed, or otherwise resolved in order for the PCs to overcome the obstacle and/or achieve the objective.

When it comes to the situational obstacles, note that there’s only a handful of them: Stormtroopers, Imperial officers, the security protecting the Death Star’s computer network, magnetically sealed doors, and Darth Vader. Rather than introducing entirely new elements, the lesser obstacles get mixed and remixed constantly: Stormtroopers scanning the ship. Stormtroopers guarding the ship. Stormtroopers attacking them in the brig. Stormtroopers chasing them through the corridors. Stormtroopers guarding the ship again.

RAID SCENARIOS

Let’s digress for a moment and talk about raid-type scenarios in general.

John Tynes’ Three Days to Kill module is my personal touchstone for this. It certainly wasn’t the first raid-type module ever published, but it was the one which, for me, made the concept really gel definitively (primarily because Tynes boils it down to an essential core and clearly spells out exactly why he designed the scenario the way that he did; in other words, he breaks down the scenario structure for the GM).

John Tynes’ Three Days to Kill module is my personal touchstone for this. It certainly wasn’t the first raid-type module ever published, but it was the one which, for me, made the concept really gel definitively (primarily because Tynes boils it down to an essential core and clearly spells out exactly why he designed the scenario the way that he did; in other words, he breaks down the scenario structure for the GM).

Basically, there are three parts to a basic raid scenario (which Tynes describes as a “Tom Clancy-style special ops mission”):

First, it largely functions using the same room-and-key design of a location-crawl.

Second, the target location is designed in such a way that the PCs can grok the entire floorplan and some (or all) of its defensive measures. (You’ll note that this is distinct from a typical dungeoncrawl, where it is virtually impossible and usually antithetical to the desired gameplay for the PCs to be able to predetermine the entire floorplan.)

Third, the target location should generally feature lots of potential entry points (allowing the PCs to select their approach and make meaningful tactical decisions about how to carry out the raid).

Fourth, the defensive forces should be designed to respond as an active opposition force.

Over the years I’ve refined this structure to include adversary rosters in order to make it easier to key patrol patterns and also to make the defensive forces more dynamic in actual play.

The intended form of play is that the PCs will (1) learn about the target location, (2) have time to plan their raid, and then (3) execute their raid against active opposition.

THE DEATH STAR RAID

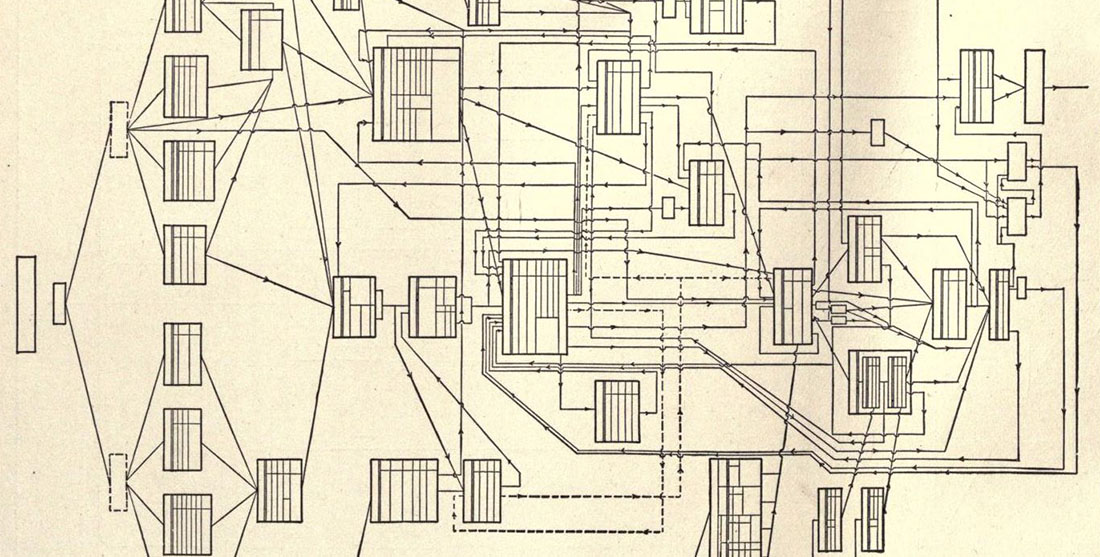

Once you understand the basic raid structure, the potential trap for a Death Star-style raid is trying to map out the entire space station. That’s valuable for smaller raid scenarios (particularly if you prep it in a way that the blueprint can literally be presented to the PCs so that they can use it during planning), but a space station is just too big for that to be convenient. (Even a space station much, much, much smaller than the Death Star.)

So in planning out a raid on the Death Star, you’ll need to figure out how to design the raid on a slightly more abstract level. Let’s look back at our list of four elements which makes the Death Star sequence tick:

1. Generally speaking, do NOT determine how the PCs will gain access to the station. Instead, take a step back, think about all the ways people can enter the station, and then figure out how those entrances have been secured. Sketch those out briefly. As with any other raid scenario, it’s now up to the players to (a) learn about them and (b) figure out how to bypass them.

2 & 3. Figure out 1-3 objectives that the PCs want on the space station and/or primary obstacles they need to overcome to escape the station once they’re onboard it. (The players may have already determined at least some of this for you when they made the decision to raid the space station in the first place: Why are they there?)

4. Prep your grab bag of 4-6 situational obstacles that can complicate the PCs’ efforts to reach and achieve the objectives/primary obstacle. Include 1-2 big, notable bad guys (Darth Vader, Tarkin). Include some interchangeable mooks (stormtroopers, officers). Include some passive security features (computer network, magnetically sealed doors).

Finally, briefly sketch the general layout of the station. As noted, this shouldn’t be a hyper-detailed map: You want to know the major features of the space station (docks, brig, bridge, engineering cores, Stormtrooper barracks, etc.) and you probably want to have a general sense of where they are in relation to each other (brig is on the upper levels, docks on the lower levels, etc.).

A flowchart structure can work well for this, giving enough structure for the PCs to make meaningful choices without getting bogged down in an unnecessary superfluity of detail.

SITUATIONAL OBSTACLES

As you’re developing this flowchart, try to include at least 1-2 locations between the entrances and the various objectives/primary obstacles. These are the locations where the PCs can encounter some of the situational obstacles. For example, in order to get from the docks (where the PCs enter the Death Star) to the brig (where the princess is being held) you need to pass through the central elevator shafts (giving Imperial officers or other personnel a chance to spot you).

You can sketch out what situational obstacles are found in each location, if you like:

DOCKS

- 2 stormtroopers in the docking bay itself

- 2 imperial officers overseeing the docking bay from the control room

- Magnetically sealed door on the control room

THE DEATH STAR RAID IN PLAY

And that’s basically it. At this point, you’ve got enough material that your players should be able to engage with it and you can respond dynamically whenever they do.

Don’t feel trapped by your prep. Remember, that what you’ve been designing are tools: If they’re in the brig and they blow their Bluff check, send in some stormtrooper squads. If they feel trapped, don’t think they can fight their way out, and they say, “There must be another way out of here! Can we get out through the vents?” think for a moment and then say, “Sure. That works. You can blast a hole in the wall over there and drop down onto the garbage disposal level.” You didn’t prep a garbage disposal level, but it makes sense that a space station would have one, right?

The garbage disposal room they drop into feels like a significant location, though, so let’s add a situational obstacle. Stormtrooper guards? Hmm… No. They just got away from stormtroopers up above, and who would bother guarding garbage? Let’s throw a magnetically sealed door here and… compacting walls? Yeah, that sounds good.

BEYOND THE DEATH STAR

Obviously this basic structure can be used for more than just space stations: Any raid targeting a sufficiently large facility can be set up this way.

As an exercise, you can break down the raid on CIA headquarters in Mission: Impossible and design it as a scenario. The objective is obvious (the NOC list kept in the vault). What are the potential entrances to the facility? What is the primary obstacle(s) that prevent them from leaving once they’re in? What are the situational obstacles that the GM can use to complicate their mission (if they choose to accept it)?

Of course, some would-be “challenges” will have obvious answers: Sherlock Holmes? Well,

Of course, some would-be “challenges” will have obvious answers: Sherlock Holmes? Well,