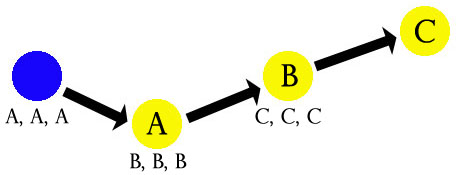

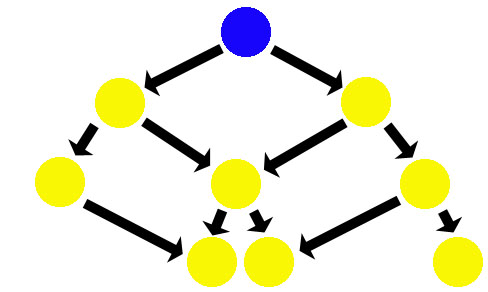

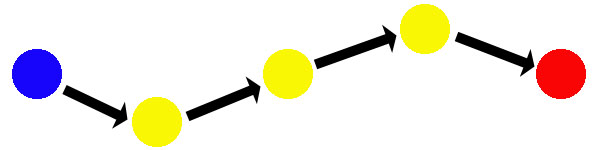

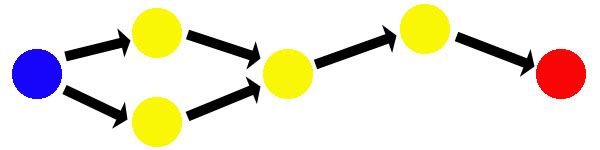

The PCs are playing agents in the Las Vegas branch of CTU. This mini-scenario begins when they receive an inter-agency intelligence report that a monitoring program established on a known terrorist operation’s bank account information has recorded payments being made on a storage unit in Las Vegas. The PCs have been authorized to execute a search warrant on the storage unit.

The scenario starts at the North Las Vegas Self-Storage on Lake Mead Boulevard (the BLUE NODE).

The storage space itself is stacked high with empty cardboard boxes. Anyone walking past the storage space when the door was open would see a bunch of boxes labeled “LIVING ROOM”, “DISHES”, and the like – but it’s all just for a show. There’s a large gap towards the back where several boxes have recently been removed: Something was being stored here and now it’s gone.

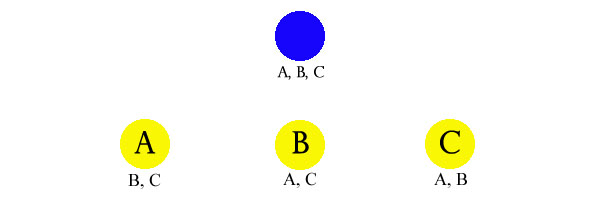

CLUE 1: Checking the rental records reveals that Yassif Mansoor signed the lease on the storage space. The address given on the lease agreement is a fake, but a routine database search turns up a Yassif Mansoor living in the Broadstone Indigo apartment complex on Azure Avenue (NODE A).

CLUE 2: The storage space contains a bellboy uniform belonging to the Bellagio hotel and casino (NODE B).

CLUE 3: There is also a disposable cell phone in the storage space. Checking the call log reveals several calls being placed to a number that can be traced to Officer Frank Nasser (NODE C).

ANCILLARY CLUE: Two detonation caps can be found behind the metal track of the storage space door. (They rolled back there and were lost.)

NODE A: YASSIF MANSOOR’S APARTMENT

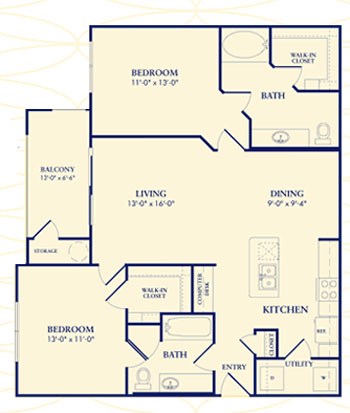

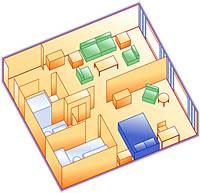

Yassif Mansoor isn’t at his apartment, but there are eight terrorists hanging out. Four of them play cards in the living room; two are watching TV in one of the bedrooms; and two more are on the balcony smoking.

CLUE 1: A large metal trash can in the storage closet off the balcony contains the charcoaled remnants of a massive amount of documentary evidence (Mansoor was covering his tracks). Sifting through the ashes reveals a few partially preserved scraps of paper, including part of a Radio Shack shipping manifest including an order number. Tracking the order reveals several pieces of electronic equipment that could be useful in building bombs. More importantly, it also gives them a credit card number and one of the fake names Mansoor was using. If they track recent activity on the credit card, they’ll find that it was used to rent a room at the Bellagio (NODE B).

CLUE 2: If the PCs can get one of the terrorists to crack under questioning, they can tell them that Yassif Mansoor was at the apartment yesterday with a cop named Nasser (NODE C).

ANCILLARY CLUE: There are six suicide-bomb vests stored in the walk-in closet. After the big bomb went off at the Bellagio, these suicide bombers were going to deliver a second wave of terror throughout Vegas. (These bombers, however, do not know the actual target of the big bomb. That information was sequestered.)

NODE B: THE BELLAGIO

If the PCs tracked Mansoor’s credit card activity, then they know exactly which suite he’s rented at the Bellagio. If they only know that something might be happening at the Bellagio then the room can be tracked down in a number of ways: Bomb-sniffing dogs; questioning the staff; surveillance; room-by-room canvassing; reviewing security tapes; and so forth.

Mansoor and six nervous, heavily armed terrorists are waiting in the suite with the Big Bomb (which they snuck into the room on luggage trolleys using bellboy uniforms).

CLUE 1: Yassif Mansoor probably won’t break under questioning, but merely identifying him should allow the PCs to track down his home address (NODE A).

CLUE 2: Sewn into the lining of Mansoor’s jacket is a small packet of microfilm. These contain records indicating that Frank Nasser of the Las Vegas police department is guilty of embezzling from a fund used for undercover drug buys. Mansoor was using these records to blackmail Nasser. (NODE C)

NODE C: FRANK NASSER

Having been blackmailed by Mansoor, Nasser has been helping the terrorist in a number of different ways. (The C4 for the suicide bombers, for example, was taken from a police lock-up Nasser was responsible for. And Nasser intimidated a beat cop into dropping a speeding ticket issued on one of Mansoor’s men.)

CLUE 1: Nasser is more likely to crack under questioning than Mansoor (particularly if the PCs reveal that they have hard evidence of any of his wrong-doing). But he’s also aware of the consequences: If he can, he’ll try to cut a deal before answering their questions.

CLUE 2: Nasser can also be placed under surveillance. He will check in at both the Bellagio and Mansoor’s apartment before the bombings occur.