It’s a fairly typical piece of advice for neophyte GMs that they can design scenarios “just like dungeons”: Replace each room with a location or scene; replace each door with a clue.

The logic behind this approach is fairly clear: Most GMs get started by running dungeon scenarios, most GMs are very successful in running dungeon scenarios, and most GMs find it relatively easy to prep dungeon scenarios.

(The reason for this is the dungeon’s clarity of structure, self-controlled pacing, and robust design. But that’s largely a topic for another day.)

But this analogy is problematic from both directions. First, as we discussed previously, doors or hallways in a dungeon are a robust transition:

If you’re standing in a room, the presence of a door or hallway into the next room is generally obvious and its purpose self-evident. Clues, on the other hand, are fragile in isolation: They can be missed, mistaken, or ignored.

Clues also allow for omni-directional relationships. A dungeon room, however, typically can’t have a door to another location on the opposite side of the dungeon. The geography of the dungeon is rigid (and usually reversible). The geography of a mystery can be flexible (and is often one-way).

So, in general, I think – despite its ubiquity – this is actually really bad advice to give to neophyte GMs.

ROBUST STRUCTURES: But there are lessons that can be learned from the analogy.

First, dungeons work because the doors are robust transitions. Ergo, we should try to find equally robust transitions in other scenario structures. The Three Clue Rule, for example, is a way of accomplishing that with a mystery scenario.

Similarly, as we’ve discussed before, it’s possible for the typical robustness of the dungeon geography to mislead us into a false sense of complacency: A mandatory secret door, for example, can create a very fragile dungeon structure. That’s something to be aware of when designing dungeon scenarios.

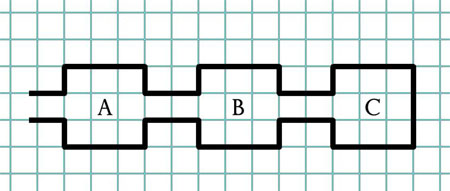

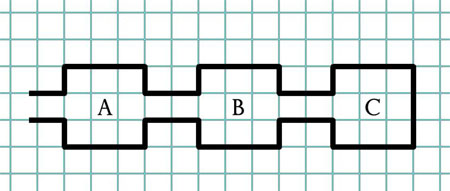

EPHEMERAL BARRIERS: Consider our simple dungeon example again:

Note that the structure of the dungeon essentially “forces” the players to experience area B: If they could pass directly from area A to their goal in area C, they would. In this sense, area B functions as a “barrier” for the PCs.

Most dungeons are filled with such “barrier content” – content experienced only because the PCs are forced to physically move through those areas in order to reach the areas they want to go to.

But as the PCs gain resources to become proactive, the GM can’t just put barriers in their way. This is why high-level dungeons so often fail: The PCs can simply scry, fly, stoneshape, and/or teleport their way past the old geographical or terrain-based barriers the GM was once able to use to force them into experiencing content.

Some think empowering players like this is a bug. I tend to think of it as a feature. But it does mean that if you want your players to take a journey, you’ll need to make each pit stop interesting. Actually, more than interesting: Each pit stop needs to become a center of gravity, capable of drawing the PCs in for a closer look.

This is where applying some of the lessons you’ve learned from node-based scenario design can be usefully applied to your dungeon scenarios: Effective node-based design, after all, is all about creating centers of gravity for your nodes.

In designing your dungeons, look at each room or major area: Is there a way to make the PCs want to go there and experience that content? Or, alternatively, is there a way to make the content proactive so that it will come and seek out the PCs?

CLUE-BASED DUNGEON NAVIGATION: Consider, too, what happens when you bring clue-based navigation into the dungeon.

For example, the players might find a diary indicating that a “silver throne” can be “pushed aside to reveal a staircase”. Such a clue can easily send them to rooms on the opposite side of the complex, leave them looking for more information about the location of silver thrones, or anything inbetween.

In other words, dungeons can be thought of as a collection of nodes (with each room or area being a separate node). Traditionally we default to thinking of the transition between these dungeon nodes as strictly a geographical affair. Occasionally we may also throw in some randomly-triggered content, but even when we do that, we’re still limiting ourselves. There’s no reason we can’t lace a dungeon scenario with other forms of node navigation: Clues, temporally-triggered events, proactive content, trails, and the like.

The result is a richer and more rewarding dungeon scenario that will keep your players engaged in a multitude of ways.

Go to The Secret Life of Nodes

FURTHER READING

Using Revelation Lists

Game Structures

Hexcrawls

5 Node Mystery

Gamemastery 101

Is this the last part of the series? I was just getting used to it and looking for more. Great series anyway, I really enjoied reading it. It gave me some now inspiration of how to design and prep my adventures, though I’m not sure whether I’ll go strictly with a node-based approach, because I’m seldom gming mystery adventures.

The last for the moment. I’ve got a couple of ideas for tie-in columns lurking on my hard drive, but I haven’t actually figured out what I’m going to fill the site with for November.

But, for the most part, this represents the “grand total” of my thoughts on node-based scenario structures. At least, so far. There’s quite a bit of “practical tip” type stuff that will probably crop up in the “Running the Dungeon” stuff I’m attaching to my Ptolus campaign journals.

Just re-read through the essay series. Simply put, this material should have its own dedicated chapter in the next DMG. Well explained, well structured advice that every novice GM should take to heart. Having been stuck outside Tabletop RPGs for a few years due to lack of local groups, your articles never fail to rekindle my interest in the hobby.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I think i’m going to design a flowchart…

Great series, thank you. I stumbled upon this as I looked for ideas for writing my first proper adventure in ages – it’ll be a great help, thanks.

Wow! Thanks for the same day response! I was trying to form my questions I forgot to say thanks. I’m sort of a new DM and I’m grateful to have your website and the ability to “stand on the shoulders of giants” as it were.

I’ve read [xandering] the dungeon before this (no doubt I will again) and I thought it was great advice. It really worked and made small dungeons I’ve run much more exciting.

Now this is a pretty clear article – advanced node based design part 6 – where you seem to encourage ideas of node based design for dungeons.

Heck – “each room or area being a different node”. I’ve seen published adventures with dungeon designs that when I plotted them were screaming layer cake.

I liked the idea of dungeon node dungeons. Although also in this article, you call it only one method of travel within the dungeon.

So another question for you…basically why advise GMs not to use nodes in dungeons in don’t prep plots, and instead advise [xandering] for dungeons? Are [xandering] and nodes partly similar? What part of these node based articles would you advise for dungeon design?

Thanks again! I feel like picking up my adventure canvas soon.

[…] Escenarios “definidos como dungeons” (enlace original). Básicamente, una par de reflexiones sobre la construcción de escenarios usando una estructura […]

Thank you so much for these articles! I often have trouble with my games either being too linear and railroady, or so free-form that there’s no real story going on at all.

I tried your method for a one-player 13th Age game I ran today, and it went brilliantly. The player had plenty of choices to make, and I think the choices actually became more meaningful because I didn’t have to come up with the consequences on the spot.

Even when he did eventually do something unexpected, my overall plot framework helped me turn that into a new route through the plot, essentially adding in a new node. Having a framework in mind gave me the confidence to improvise without worrying about the plot unravelling completely.

Now for my next session, I think I’ll do some [xandering]…

This was so well-written and helpful. Thank you.