Up to this point I’ve been fairly vague about exactly what I mean by a “node”. This is largely because there isn’t really a hard-and-fast definition of the term.

In generic terms, you can think of each node as a “point of interest”. It’s the place (either literally or metaphorically) where something interesting can happen and (in most cases) information about other interesting things can be found.

In my experience, nodes are most useful when they’re modular and self-contained. I think of each node as a tool that I can pick up and use to solve a problem. Sometimes the appropriate node is self-evident. (“The PCs are canvassing for information on recent gang activity. And I have a Gather Information table about recent gang activity. Done.”) Sometimes a choice of tool needs to be made. (“The PCs have pissed off Mr. Tyrell. Does he send a goon squad or an assassin?”) But when I look at an adventure, I tend to break it down into discrete, useful chunks.

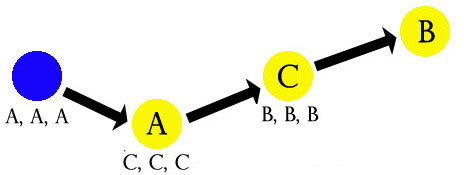

Chunks that become too large or complex are generally more useful if broken into several smaller nodes. Chunks that are too small or fiddly are generally more useful if grouped together into larger nodes. The “sweet spot” is about identifying the most utilitarian middle-ground.

(To take an extreme example: “All the forestland in the Kingdom of Numbia” is probably too large for a single node. On the other hand, 86,213 separate nodes each labeled “a tree in the Forest of Arden” are almost certainly too fiddly. Is the appropriate node the “Forest of Arden”? Or is it twelve different nodes each depicting a different location in the Forest of Arden? I don’t know. It depends on how you’re using the Forest of Arden.)

Let’s get more specific. Here are the sorts of things I think of as “nodes”:

LOCATIONS: A place that the PCs can physically go. If you think of a clue as being anything that “tells you where to go next”, telling the PCs about a specific place that they’re supposed to go is the most literal interpretation of the concept. Once PCs arrive at the location, they’ll generally find more clues by searching the place.

PEOPLE: A specific individual that the PCs should pay attention to. It may be someone they’ve already met or it may be someone they’ll have to track down. PCs will generally get clues from people by either observing them or interrogating them.

ORGANIZATIONS: Organizations can often be thought of as a collection of locations and people (see Nodes Within Nodes, below), but it’s not unusual for a particular organization to come collectively within the PCs’ sights. Organizations can be both formal and informal; acknowledged and unacknowledged.

EVENTS: Something that happens at a specific time and (generally) a specific place. Although PCs will often be tasked with preventing a particular event from happening, when events are used as nodes (i.e., something from which clues can be gathered), it’s actually more typical for the PCs to actually attend the event. (On the other hand, learning about the plans for an event may lead the PCs to the location it’s supposed to be held; the organization responsible for holding it; or the people attending it.)

ACTIVITY: Something that the PCs are supposed to do. If the PCs are supposed to learn about a cult’s plan to perform a binding ritual, that’s an event. But if the PCs are supposed to perform a magical binding ritual, then that’s an activity. The clues pointing to an activity may tell the PCs exactly what they’re supposed to be doing; or they may tell the PCs that they need to do something; or both.

NODES WITHIN NODES

In other words, at its most basic level a node is a person, a place, or a thing.

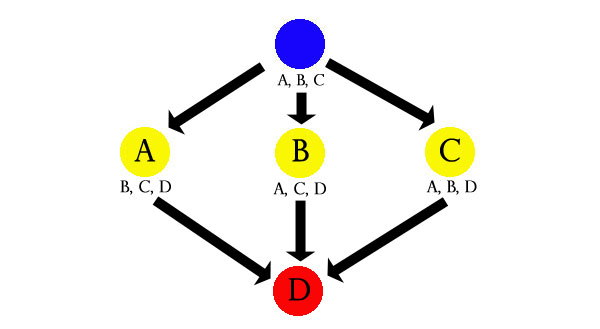

As suggested above, however, nodes can actually be fairly complex in their own right. For example, the entire Temple of Elemental Evil (with hundreds of keyed locations) could be thought of as a single node: Clues from the village of Hommlet and the surrounding countryside lead the PCs there, and then they’re free to explore that node/dungeon in any way that they wish.

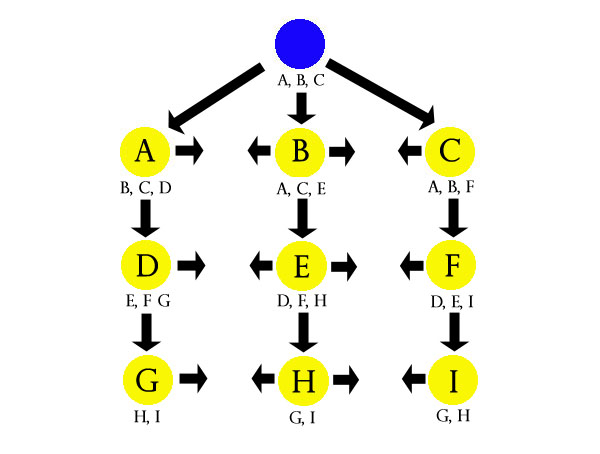

Similarly, once the PCs start looking at the Tyrell Corporation they might become aware of CEO James Tyrell, the corporate headquarters, their shipping facility, the server farm they rent, and the annual Christmas party being thrown at Tyrell’s house — all of which can be thought of as “sub-nodes”. Whether all of these “sub-nodes” are immediately apparent to anyone looking at the Tyrell Corporation or if they have to be discovered through their own sub-network of clues is largely a question of design.

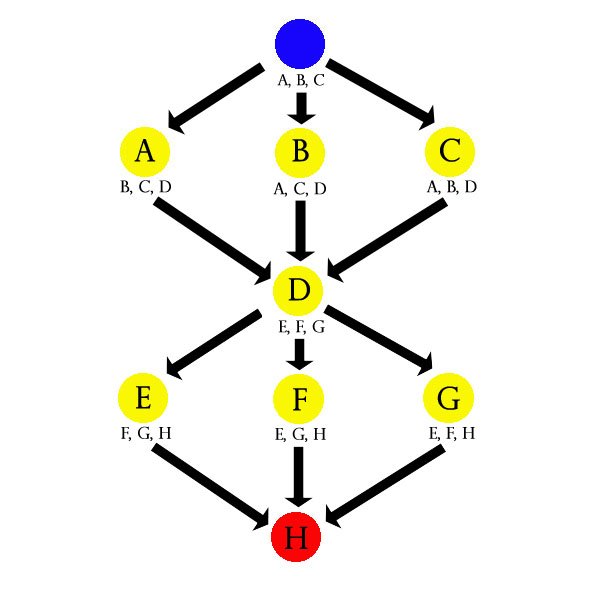

In short, you can have nodes within nodes. You can plan your campaign at a macro-level (Tyrell Corporation, Project MK-ALTER, the Chicago Sub-City, and the Kronos Detective Agency), look at how those macro-nodes relate to each other, and then develop each node as a separate node-based structure in its own right. Spread a few clues leading to other macro-nodes within each network of sub-nodes and you can achieve highly complex intrigues from simple, easy-to-use building blocks.