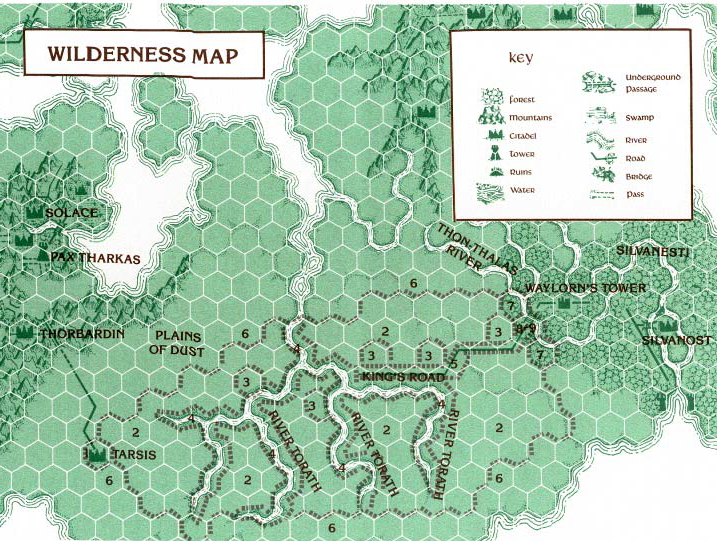

Finding locations during a hexcrawl — including locations that you are specifically looking for — is handled primarily through the navigation and encounter rules.

SIMPLE EXPLORATION

In the simplest form of hexcrawling, expeditions will automatically encounter the keyed location in a hex when they enter that hex. Therefore, finding a location you’re looking for — e.g., the Tomb of Sagrathea — is simply a matter of finding the correct hex.

This may be slightly more difficult for the PCs to pull off reliably if you’re running with player-unknown hexes, but the procedure remains the same: The expedition will want to navigate to the area they suspect the location to be, then move through the area in some form of search pattern until they find what they’re looking for (by entering the correct hex).

Following roads or trails, of course, may make it much easier for the PCs to hit the right hex.

BASIC ALEXANDRIAN EXPLORATION

The Alexandrian Hexcrawl includes a number of optional and advanced rules that can add complexity, challenge, and choice to exploration.

As described in Finding Locations, above, Visible and Familiar locations can be automatically found by any character passing through the appropriate hexes (just as with simple exploration). Other locations, however, are found through encounter checks, so the expedition must be in the correct hex and generate a location encounter there.

Choosing the exploration travel pace — during which the expedition is assumed to be trying out side trails, examining objects of interest, and so forth — will significantly increase the likelihood of finding the location you’re looking for by (a) reducing your speed of travel (so that you’ll spend longer in any individual hex) and (b) doubling the chance of having an encounter. Compared to moving at a fast pace, for example, the exploration travel pace makes it six times more likely that you’ll find a location.

Optional Rule – Focused Search: If the expedition is traveling at exploration pace and looking for a location that they have specific information about, the DM may allow a third encounter check per watch for that location and only that location. (Any other encounters that would normally be indicated by this check are ignored.) Obviously if the location they’re looking for isn’t in the current hex, the DM can skip this check — they are, after all, looking in the wrong place.

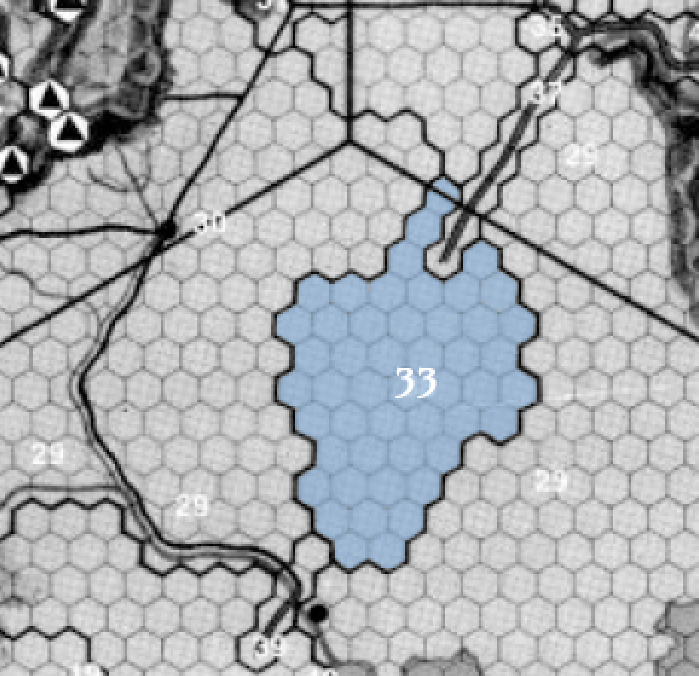

Design Note: It may seem unreasonable that you can pass through a hex and not find a location within it. But hexes are, in fact, very large. For example, the entire island of Manhattan could fit into a 12-mile hex more than five times over. If it still feels unreasonable that the PCs could move through a hex and NOT find the location they’re looking for, you might want to consider the possibility that this location should be classified as Visible.

BASECAMP EXPLORATION

If an expedition wants to perform a dedicated exploration of a specific area, they can establish a basecamp. There are two basic watch actions associated with a basecamp: Make Camp and Area Search.

BASECAMP ACTION: MAKE CAMP

As an active watch action, a character can establish a camp suitable for 4 creatures if they have tents or similar equipment to shelter them. (Horses and similar creatures do not require tents, but must still be accounted for in camp preparations.)

If the expedition does not have equipment for shelter, the character can only establish a camp suitable for one creature (either themselves or someone else) per watch action.

Optional Rule – Camp Required: Characters without a proper camp require an additional Resting action to gain the benefits of resting. (It takes three Resting actions in a row to gain the benefits of a Long Rest. If using the advanced rule for lack of sleep, it takes two Resting actions in a row to avoid the consequences for not resting.)

Optional Rule – Favorable Site: A character can perform an active watch action to make an Intelligence (Nature) or Wisdom (Survival) check against the Forage DC of the terrain. On a success, they have identified a favorable campsite. Characters performing the Forager action in a favorable campsite gain advantage on their forage checks.

The check to identify a favorable site can also be attempted as part of a Scout action.

BASECAMP ACTION: AREA SEARCH

As an active watch action, a character can search the wilderness in the hex cluster around their base camp. Multiple characters performing this action simultaneously can form a search group (or multiple search groups if they split up).

Encounter Checks: Make a normal encounter check for the base camp, even if no characters remain in the camp. (An encounter would indicate that the base camp has been discovered.) Make an additional encounter check for each search group. (The search counts as a travel watch for the purpose of making this encounter check.)

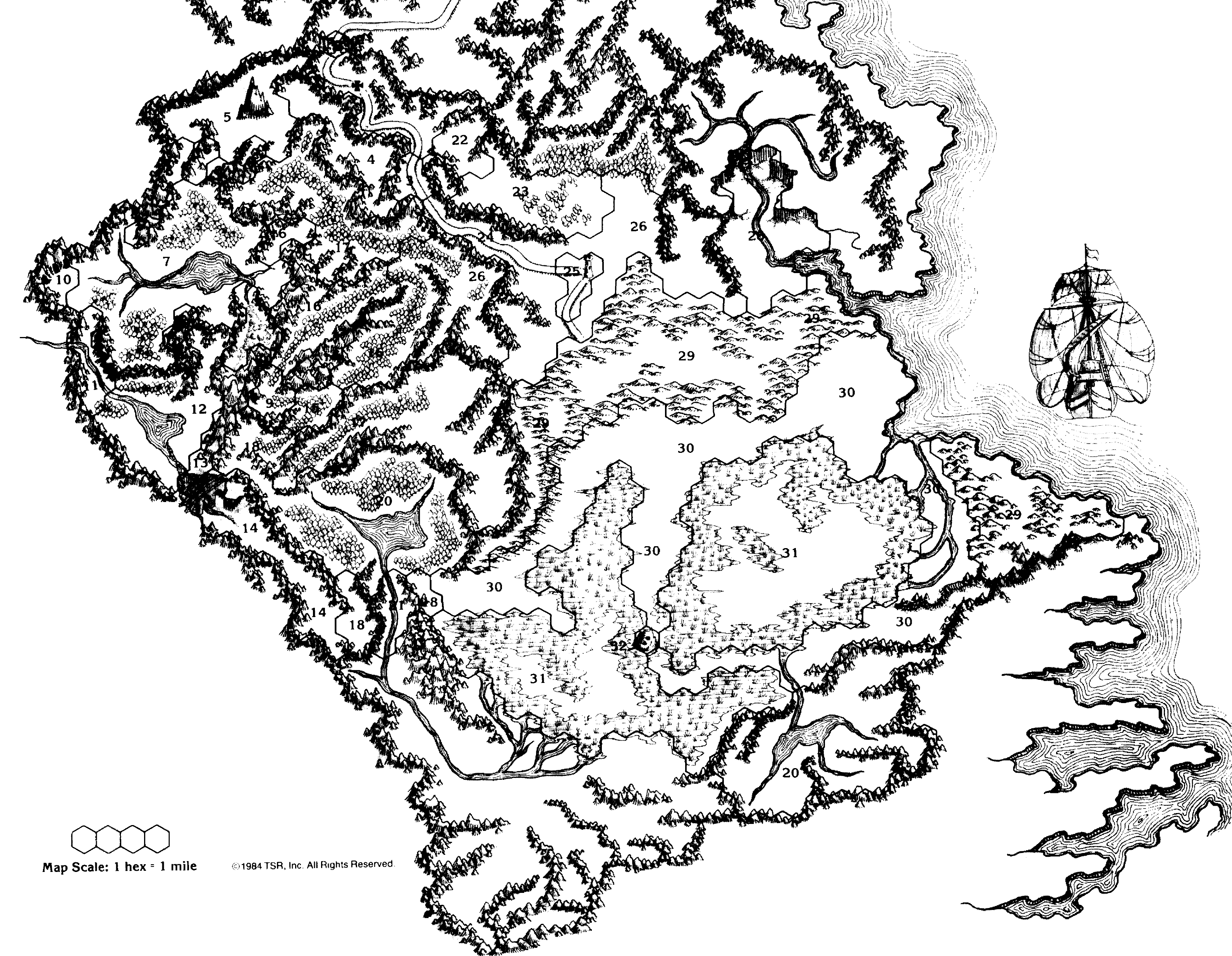

Search Area: The hex searched by a search group can be determined:

- Randomly. Roll 1d8 on the hex cluster chart below.

- Directionally, if the search group indicates the direction they are searching. Roll 1d8, with any roll other than 7-8 (the base camp hex) indicating the hex in the selected direction.

- By Hex, in which case the search group indicates which specific hex in the cluster (including the hex of their base camp) they wish to spend their time in.

Search Area – Large Hexes: If using larger hexes (or in particularly difficult terrain), it may not be possible for the PCs to reasonable travel to neighboring hexes in a single watch. In such cases, a travel watch would be required both before and after the Area Search action.

If circumstance or hex-size makes it impossible for the PCs to reach neighboring hexes even with a travel watch, then the Area Search action is limited to near-only searches in the base camp’s hex and it will be necessary to move the base camp in order to search other hexes.

Location Discovery: One character in each search group can attempt a Wisdom (Perception) or Intelligence (Investigation) check using the Navigation DC of the hex to find the location (+5 DC if the location is hidden). Additional characters in the group can assist, granting the searcher advantage on their check.

If there are multiple locations, randomly determine which one is found.

Note: At the DM’s discretion, they may assign an alternative DC to specific locations. If there are multiple locations, the DM may rule that an additional location is found for every 5 additional points of success.

Other Group Members: Characters performing Sentinel or Tracker actions can join a search group. (Note that the Wisdom (Perception) checks performed by sentinels detect approaching threats, as opposed to the checks made to find locations.)