VESTIGIAL HEXES

The deeper you dig into the play experience of these modules, the clearer it is just how vestigial the hexes had become. You’re left with a very clear sense that the designers are not all that interested in hexmaps as hexmaps, and are really only including them because, as I’ve mentioned before, it was the expected thing to do.

For example, in DL1 there’s a pair region-keyed encounters with draconians where the draconians from one encounter are supposed to call out to the draconians in the other encounter, who can then move up and “close the trap.”

But these encounters are, of course, keyed to the hexmap. So the other draconians are three miles away. There’s no reality in which they’re going to show up to “close” anything until the combat is long over.

Similarly, in DL3 there’s a hilarious bit where an ice shelf in Area 13 is supposed to break loose, causing the PCs to go tumbling down a slide of ice (Area 14) and end up in Area 18:

This is written up as a quick, traumatic event. But, as you can see, the ice slide is 8 or 9 miles long.

(To be fair, this is an unintentional Moment of Awesome because it makes me think of the entire sequence as a Monty Oum video.)

You can see similar Hexmaps for the Heck of It™ in DL4 Dragons of Desolation and DL9 Dragons of Deceit, where cities are keyed to hexmaps to no real purpose.

CAMPAIGN HEXAGON SYSTEM

In DL7 Dragons of Light by Jeff Grubb, the Dragonlance modules actually employ a three-tier system of hex maps. On the region map you can see both 20-mile megahexes and 1-mile subhexes:

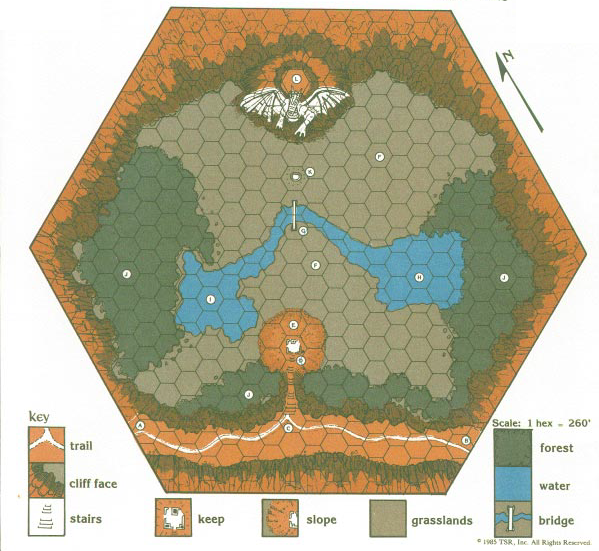

But the module also zooms into one of the 1-mile hexes and depicts 260-foot subhexes:

Although the specific measurements used here are different, this tiered approach almost precisely models the method laid out in the Campaign Hexagon System published by Judges Guild, the idea being that you can perfectly synchronize your local and regional maps, allowing you to zoom in (and out) as needed.

GUESS THE HEX

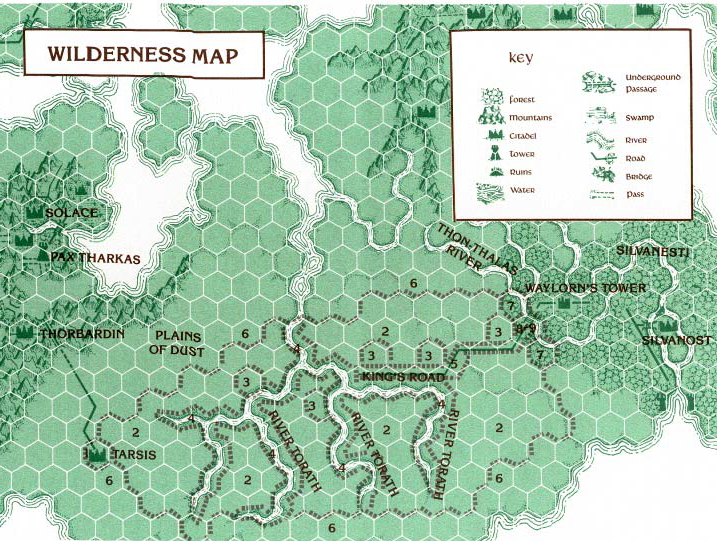

In DL10 Dragons of Dreams, another Tracy Hickman design, we return to the region-based mapping of DL1 and DL3. This particular implementation is fairly perfunctory, however:

The PCs are supposed to hitch a ride with some griffins in Tarsis, but if they don’t the scenario is backstopped with this region-based ‘crawl across the Plains of Dust.

What’s interesting here is that Hickman actually leans into what I generally consider to be the flaw with under-keyed hexmaps: The players have to blindly play a game of “guess the hex” until they find the right one.

In this case, the area is inhospitable and in order to survive the journey the PCs have to find a source of food. To do that, they need to hit one of the hexes keyed to Encounter 3 (which contain bushy plainsfruit plants).

THE WARGAME

DL11 Dragons of Glory, designed by Douglas Niles and Tracy Hickman, is not an adventure module. It is, in fact, a full-blown hex-and-chit wargame. This means, of course, that the board is a giant hexmap, this one depicting the entire continent of Ansalon at a 20-mile scale.

(The DL11 map does not include a scale, but the hexes are isomorphic with the Western Ansalon region maps in DL6 and DL8, which do indicate the 20-mile scale.)

I haven’t fully explored this wargame yet (although I hope to), but what’s notable here is that it’s designed to be integrated with a simultaneous RPG campaign. The common use of hexmaps makes it possible for the events in the wargame to have a direct affect on the narrative of the RPG campaign (and vice versa).

(At leas hypothetically. In practice, this does not appear to work quite as slickly or produce as cool a result as one might hope. But, again, I’m hoping to explore this further.)

The interesting thing here is that this very much harkens back to why hexmaps were used in RPGs in the first place: The earliest RPGs were designed to integrate character roleplaying with wargame sessions. In Arneson’s original Blackmoor campaign, in fact, the idea was that characters would earn their fortunes in the dungeon, establish fiefdoms for themselves, and then fight wars for dominance.

In Arneson’s campaign, in fact, PCs belonged to either Team Good or Team Bad, who were opposed to each other in the wargame component of the campaign. (The root of the modern alignment system.) You could actually imagine a daring reimagining of the Dragonlance Saga in which the players were simultaneously playing the heroic Innfellows, the villainous Dragonlords, and a War of the Lance wargame, with all three components dynamically interacting with each other.

THE UNDERDARK

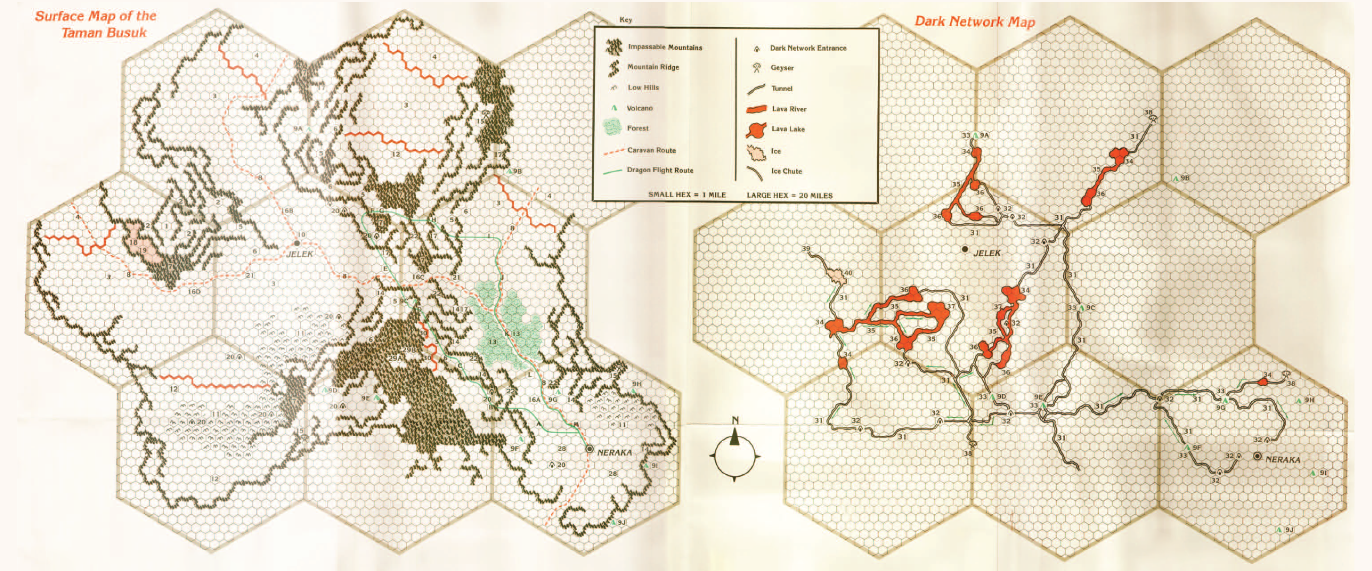

In DL13 Dragons of Truth, another of Tracy Hickman’s designs, we have yet another hexmap variation:

The poster map depicts a dual hexmap: One depicting the wilderness and another, perfectly synced with the first, showing the underdark beneath (here known as the “dark network”).

There’s not much to say about this final example, but it’s a great example of the type of utility you can glean from well-scaled maps and of the varied forms of utility the Dragonlance designers wrung from their hexmaps.

FURTHER READING

5E Hexcrawls

A Quick History of D&D

I think a big part of the issue here is that they’re not really trying to use hexmaps in the same fashion. Instead of a hexcrawl on a keyed map with plenty of content it’s largely just a method of indicating scale and distance on a map. There isn’t any expectation that most hexes would have anything in them or likely that the party would even crawl across them in that fashion. Hence why we have the 20 mile megahexes added on. They don’t represent regions or any sort of larger structure. Their placement seems fairly arbitrary. Intead they’re just a quick method of counting up a bunch of hexes. In this respect it also recalls the transparent hex overlays that TSR would release with most of their campaign setting box sets during the 2e era. Just stick it on top of an existing map in order to work out the distance.

It’s also valid to point out how vestigial this was as a method. Yes, it’s a bit more convenient than using a map scale and a ruler, but to what end? Most of the time the players are going to want to engage in a point crawl, so instead listing the distance to the connecting points would largely do most of the same job. And if the players want to move between points in some unexpected fashion? Well, I’m sure most GMs could manage to work out a general idea of distance sufficient for the needs of play.

Thanks for the history lesson! I started playing in the mid 80’s and through the early 90’s my friends and I didn’t know anyone else playing D&D. We always felt like we were missing something with the hex maps in the various modules that we bought from the local bookstore (no FLGSs at the time.) ~40 years later it helps to know that we weren’t wrong– just seeing the vestigial remnants of earlier play styles.