This article is going to make a lot more sense if you’re familiar with:

- the Dragonlance Saga

- Hexcrawls

- Pointcrawls

Dragonlance was created in 1982 by Tracy and Laura Hickman. Tracy and Laura had self-published several D&D modules, which had resulted in Tracy being hired by TSR, Inc. While they were driving from Utah to TSR’s headquarters in Wisconsin, they came up with the idea of an epic series of modules featuring what were, at the time, all twelve types of dragons.

In 1983, TSR’s marketing department identified a common theme in their survey data: Dungeons & Dragons had lots of dungeons, but where were all the dragons? In response, proposals were requested for a dragon-themed project. Two proposals were submitted – one by Tracy Hickman and one by Douglas Niles – and Hickman’s was selected. Under the guidance of Harold Johnson, an all-star team of designers and artists was assembled.

The result was a series of fourteen modules – DL1 through DL14 – consisting of twelve linked adventures, a setting gazetteer (DL5) and a wargame (DL11). These fourteen modules are the original Dragonlance Saga, which gave rise to novels, comics, calendars, miniatures and more.

Hexcrawls are a method of running wilderness adventures. The wilderness is mapped onto a hexmap and content is keyed to each hex. Travel mechanics then determine how the PCs move through the hexmap and when/how they trigger the content keyed to each hex. You can find more information on hexcrawls in the 5E Hexcrawls series.

Pointcrawls are another method of running exploration and travel adventures. A map is prepped with multiple points connected by paths. Content is keyed to each point, and the PCs can maneuver through the pointmap by choosing one of the paths connected to whatever point they’re currently in. Pointcrawls are often used to model wilderness trails, but can have varied applications. You can find more details about pointcrawls here, and there’s an example of a pointcrawl here as part of the Descent Into Avernus Remix.

Hexcrawls, like dungeons, have been around since the earliest days of the hobby. Even before Dungeons & Dragons was published, Dave Arneson was using the hexmap from a game called Outdoor Survival to run wilderness adventures for his Castle Blackmoor campaign.

During the ‘80s, however, unlike dungeons, hexcrawl play slowly withered away. I believe there were a couple reasons for this. First, hexcrawls are not a terribly efficient form of adventure prep. Because you’re keying content to a bunch of different hexes without knowing exactly which hexes a group of PCs might visit, hexcrawls are best suited for scenarios in which the PCs will repeatedly engage with the same chunk of wilderness (so that they’ll encounter different hexes over time).

This makes hexcrawls a great fit for open tables (like Dave Arneson’s Castle Blackmoor or, later, Gary Gygax’s Castle Greyhawk), in which there are multiple groups of PCs exploring the area. But as play increasingly shifted towards dedicated tables (with a smaller number of players who are all expected to attend each session) and plot-based play, it made less and less sense to prep hexcrawls.

For similar reasons, it was difficult for RPG publishers to print fully functional hexcrawls within the constraints of the pamphlet format used for adventure supplements. Very few true hexcrawls were ever published, and those that did see print were never truly complete. TSR, in particular, would usually only print hexmaps with adventure-relevant locations keyed to them (leaving vast swaths of unkeyed territory for the DM to fill in, assuming it even made sense to do so in the first place). So, unlike a dungeon, new DMs couldn’t just pick up a published hexcrawl and run it. They also didn’t have any fully developed examples to base their own designs on.

By 1984-86, when the Dragonlance Saga was published, the industry and hobby were already at a turning point. Although TSR would continue depicting wilderness areas using hexmaps until the early ‘90s, actual hexcrawls were more or less done. (They wouldn’t reappear until the early 21st century.) It’s interesting, therefore, to look at how the Dragonlance Saga was using hexmaps as an example of this transitional period.

This was even more true because the Dragonlance Saga was a radically experimental project. Not only had nothing of this scope been attempted before, but the Saga was also a massive multimedia experience – not only the famous Chronicles trilogy of novels, but also integration with the BattleSystem™ miniature combat system and a full-fledged wargame. All of this was in service of created an epic fantasy adventure for D&D.

That might seem utterly unremarkable today. (“An epic fantasy campaign for D&D? Of course. Eighteen of them get published every month.”) But this was also something new: Del Rey Books had only recently revealed to the world that LOTR-esque fantasy epics like Terry Brooks’ Sword of Shannara or David Eddings’ Belgariad could be hugely successful, and it was this type of story that Tracy Hickman and the Dragonlance design team wanted to bring to D&D for the first time.

This meant that the designers were also trying to figure out how to do an adventure like this. So they were experimenting with adapting existing adventure design techniques and creating new techniques at the very moment that hexcrawls were dying out.

So when we look at the myriad ways that the Dragonlance Saga used hexmaps, we’re peering into an RPG skunkworks that was grappling with something utterly new and fighting with all of their ingenuity to bring players and DMs a grand experience.. Once we do that, I think we can really appreciate these innovations for what they were, and also learn from them.

REGION CRAWLS

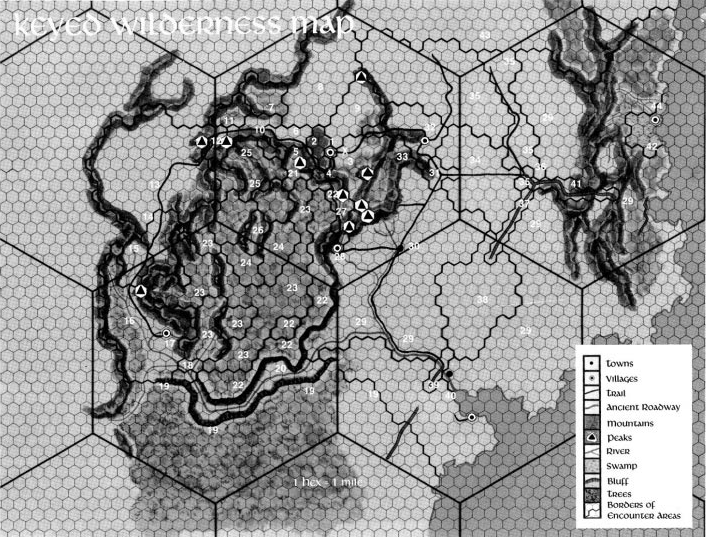

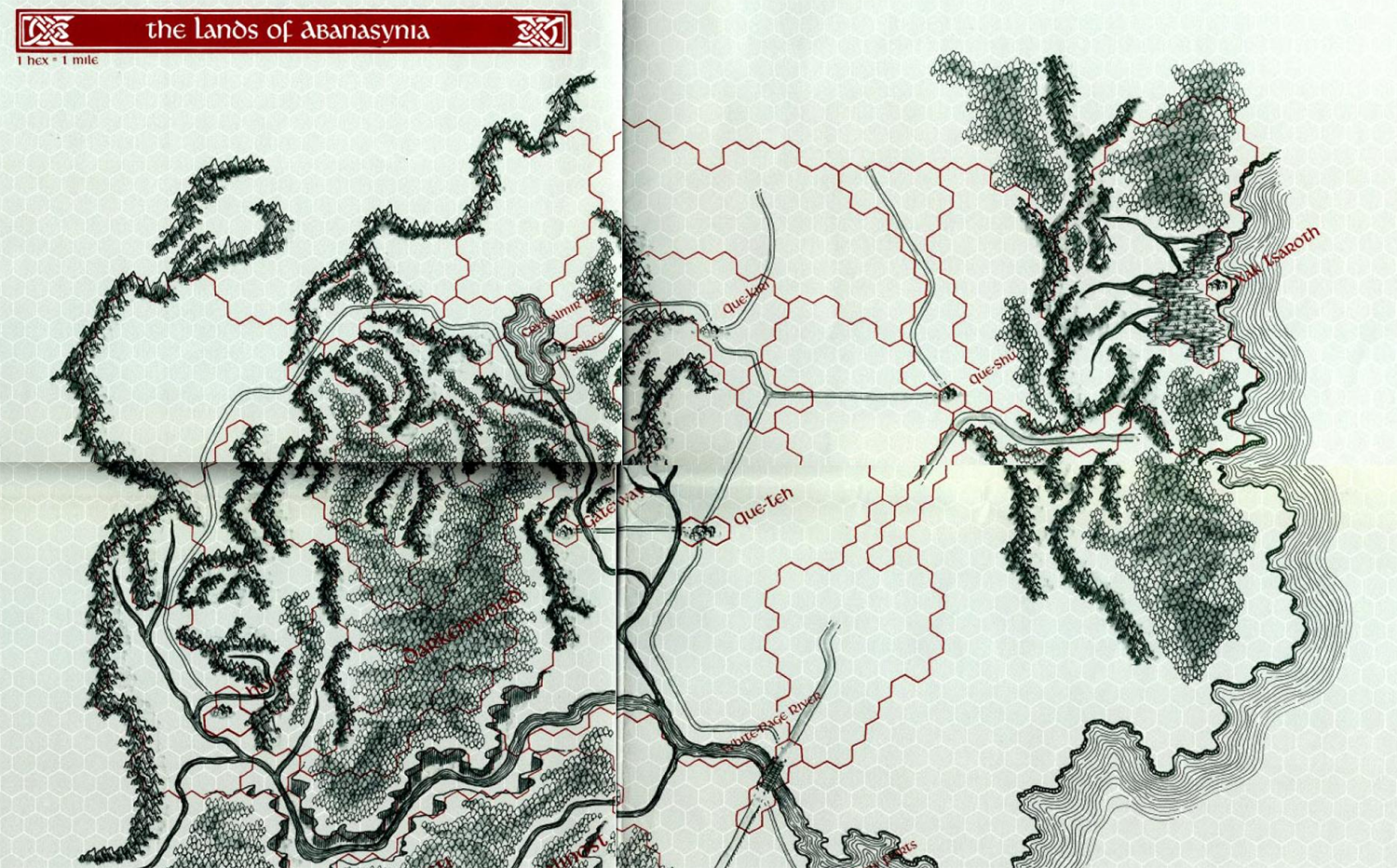

DL1 Dragons of Despair features this hexmap:

At first glance, this sure looks like a hexcrawl. It even features sub-hexes. (The larger, 20-mile hexes are made up of smaller, 1-mile hexes.)

But if you take a closer look, you’ll notice that the map is actually broken up into regions using thin black lines. It’s these regions which are actually keyed.

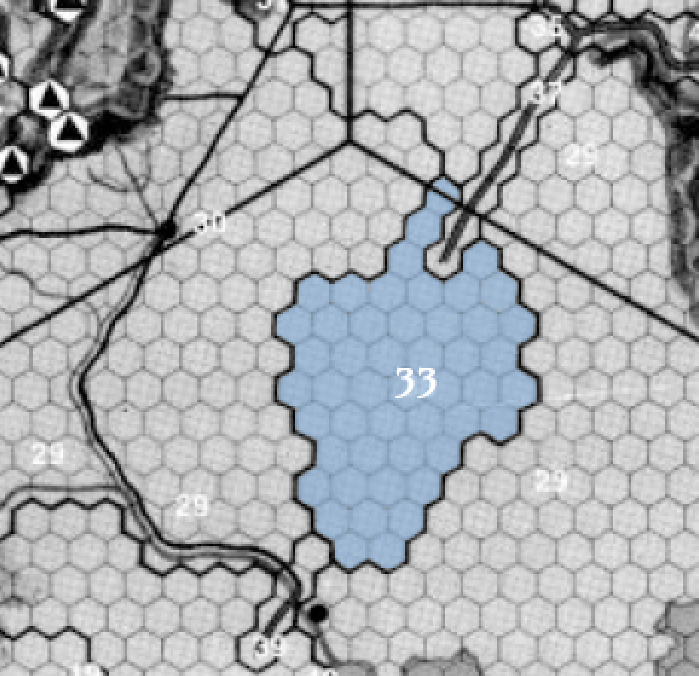

For example, the entirety of region 33 is keyed as the Kiri Valley:

The forest darkens and thickens beside an ancient trail. A cold, dry stillness hovers in the air, and the trees are knotted and bent. Everything seems to watch you.

An evil wizard died here long ago. Only his essence remains.

This technique allows Hickman’s key to cover the entire map without needing to key content to every individual hex.

If I was redoing this or taking inspiration from this, I would probably ditch the hexes entirely. Although they can be hypothetically helpful in counting out movement, they’re mostly getting in the way and badly impairing the legibility of the map.

(The 20-mile hexes do appear to correspond with a larger map printed in later modules, most notably DL11 Dragons of Glory, which we’ll discuss later. So there might be an argument for keeping those.)

JUST THE MAP, MA’AM

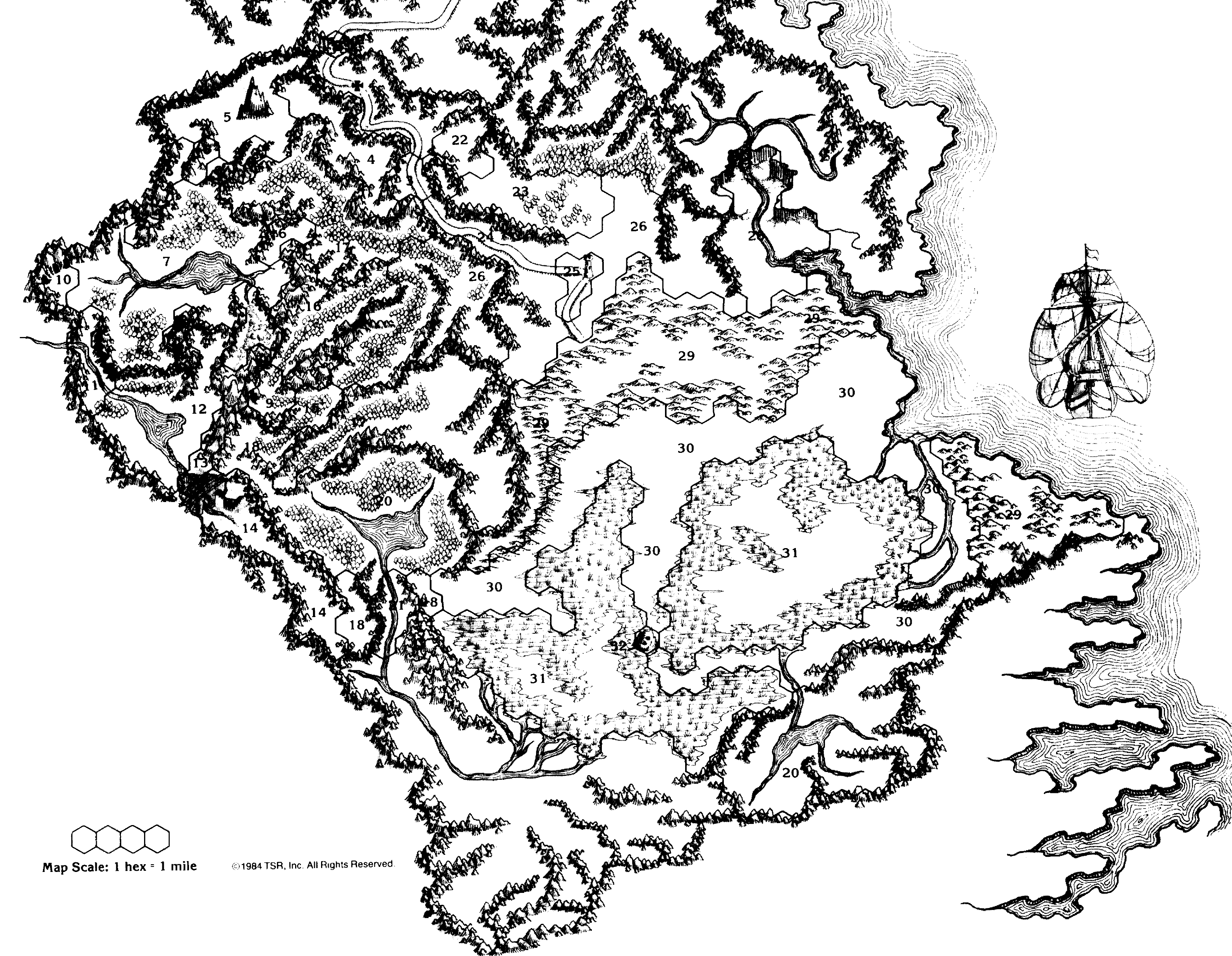

DL2 Dragons of Flame by Douglas Niles features an all-new, full color map of the same area which has also been expanded to the south:

(This is only a sample of the large map, which extends down to a fortress called Pax Tharkas. Oddly the map lists the scale as 1 hex = 2 km, but the hexes align perfectly with the DL1 map.)

This map is an extreme version of many hexmaps that would follow: Rendered using hexes because that had become the expected norm for wilderness maps, but completely divorced from any key or structure that would make the hexmap relevant.

SURPRISE POINTCRAWL

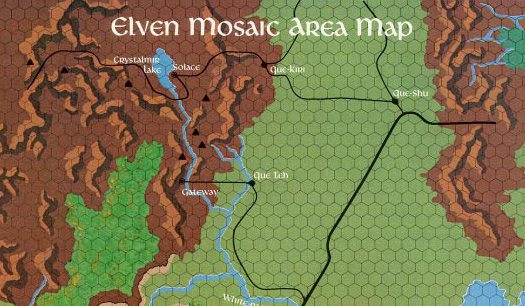

DL3 Dragons of Hope, once again by Tracy Hickman, features a large, unkeyed poster map that unifies the previous hexmaps and then adds a big region to the south of Pax Tharkas (where DL3 takes place).

(Sorry for the poor image quality. Unfortunately, I only have a digital copy of this module and when Wizards scanned the PDF they completely botched it.)

This map seems pretty clearly intended for players, but it’s an odd one. Since DL2 didn’t feature regions, the middle of the map just… doesn’t have them.

The new DL3 regions were keyed on a separate inset map, which looked like this:

As you can see, the hex borders were eliminated. This makes the regions much easier to pick out, but obviously obfuscates the hexes.

The more crucial thing is that, although this looks like it’s meant to be run like the region-crawl in DL1, it’s actually keyed to work like what we would now call a pointcrawl. Here’s an example:

3. Southern Road

The broken remains of an ancient roadway glitter with windswept ice. Here and there, old monuments of stone jut from the frozen ground. Their surfaces are covered with snow-filled runes.

To the south, the way branches. The roadway, mostly covered in snow, turns to the east. To the west is a mountain pass that leaves the road. A set of footprints, short of step, follows the southwest route.

You’re not navigating by hex here. You’re choosing whether to follow the road or the pass and then you’re proceeding to the next keyed encounter along the path you’ve selected.

This topic is serendipitously timed for me. I recently started trying to add the locations from the Tales of the Lance boxed set to the DL1 wilderness map. I’m curious to see where you’ll go with this.

I’m also a bit puzzled, despite having read your series on hexcrawl structure, as to what the advantage is of having a fully pre-keyed map over using some kind of procedural content generator (such as the Talis card system in Tales of the Lance) to stock hexes on the fly?

> what the advantage is of having a fully pre-keyed map over using some kind of procedural content generator … to stock hexes on the fly?

Stocking hexes on the fly will do in a pinch, but pre-keying your map lets you create rumours and connections between hexes, turning it from a random mishmash that just happens to the players into a coherent world built by the DM – inspired by random generators – that the players can make *meaningful* choices in.

For me just having a single line of text describing each hex lets me start weaving things together and getting a feel for a region.

To expand on Tom’s reply, this really boils down to the foundational principles of smart prep: If you can improvise it at the table, improvise.

And the Alexandrian Hexcrawl includes stuff like that: I’m comfortable improvising small lairs, so I’m fine having a % Lairs value on the encounter table and then just improvising the lairs generated by that. If someone was less comfortable improvising lairs, what I’d recommend is printing off 10 or so Dyson Logos maps and putting them in a TBD Lairs folder. If a lair is indicated, you could then grab one of those maps to serve as the lair and provide the foundation for improvising or quick-prepping the lair in a 15 minute break.

But no matter how good you are a GM, there’s stuff you can’t improvise. Focus your prep on that. For a hexcrawl that’s going to be (for me):

– larger maps

– props (including treasure maps)

– detailed lore

– integrated regional design

And so forth.

Something else to consider if you’re improvising everything is the random railroad. If the PCs cannot get any meaningful insight about a region before deciding where to go, their choice of direction is meaningless. There are ways to work around that (and, similarly, ways to work around the lack of cross-connections in general) even if you are improvising literally everything, but you’ll need to be aware of the issue and take special effort to address it.

Also, from a practical standpoint, running a hexcrawl means having a lot of balls in the air. You’re already tracking movement, watch actions, encounter checks, etc. Having the actual hex content prepped is also just a nice way of taking one of those balls out of the air.

Another method of prepping a hex map fits right in with what Justin is saying. Its a concept which comes from Adventurer Conqueror King, which uses the idea of static places of interest and dynamic places of interest, where static PoI are keyed content which is fixed on the map, like any other keyed location.

Dynamic PoI is either prepped or procedurally generated content that gets dropped into an empty hex where the PCs would otherwise find a location. Once you drop in a dynamic PoI it becomes static, so no quantum ogres are made.

It’s basically the next level of a % Lairs value, but you aren’t limited to typical lairs.