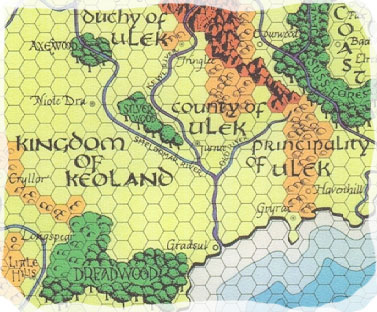

The basic, traditional design of a hexcrawl looks something like this:

(1) Draw a hexmap. In general, the terrain of each hex is given as a visual reference and the hex is numbered (either directly or by a gridded cross-reference). Additional features like settlements, dungeons, rivers, roads, and polities are also typically shown on the map.

(2) Key the hexmap. Using the numbered references, key each hex with an encounter or location. (It is not necessary to key all of the hexes on the map.)

(3) Use (or design) mechanics which will let you determine how far the PCs can move while traveling overland. Determine the hex the PCs start in and track their movement.

(4) Whenever the PCs enter a new hex, the GM tells them the terrain type of the hex and triggers the encounter or location keyed to that hex: The PCs experience the event, encounter the monsters, or see the location.

In the traditional structure, it’s also expected that the PCs will be mapping the hexes as they explore.

And that’s pretty much it.

ANALYZING THE CRAWL

As we look at this basic structure for the hexcrawl, we can begin to see some common features of the ‘crawl structure in general.

Default Goal: The default goal of a hexcrawl is exploration. This notably lacks a strong, specific motivator. In a dungeoncrawl, as we discussed, the default goal is to “find all the treasure”, “kill all the monsters”, or some other variant of “clear the dungeon”. Exploring and mapping the dungeon is usually a part of this experience, but the exploration is primarily a means to an end.

Thus, over the years, various goals have been grafted onto the hexcrawl structure to provide a strong motivation for the exploration. (For example, the hexcrawl campaign I’m currently designing takes place on the edge of civilization and there are bounties paid for those who first make interesting discoveries in the wilderness.) But I suspect one of the reasons hexcrawling faded away in the early days of the hobby is because, unlike dungeoncrawling, it lacked a clear, default goal to provide strong motivation and a reward structure.

Default Action: Just like a dungeoncrawl, the default action of a hexcrawl is “pick a direction and go”.

Easy to Prep: In terms of robust design, hexcrawls are very easy to prep. If it’s difficult for the GM of a dungeoncrawl to forget to include a door, it’s even more difficult for a GM to prep a hexcrawl in which the players can’t pick a direction to go. (If the GM isn’t keying every hex, there is a slight danger that they won’t include a sufficient density of content to make play interesting. This is a minimal risk, but consider something like X1 Isle of Dread: Presented as the introductory hexcrawl wilderness scenario for BECMI, the content of the module is actually too sparse to be effectively run as such.)

In terms of prep load, however, hexcrawls can be a little more difficult. Partly this is because there’s no natural “end point” for prepping a hexcrawl: Trying to key an entire world (or even just a full sheet of hexes) can look pretty daunting, and early game manuals weren’t very instructive in terms of explaining how prep load could be managed.

But hexcrawls can also represent a heavy prep load because any given hex can literally require just as much prep as an entire dungeon (if it, for example, has a dungeon in it).

Easy to Run: Once given a proper game structure, I find hexcrawls very easy to run. Even moreso than dungeoncrawls the content of the hexcrawl is naturally firewalled into discrete sections.

One thing that makes hexcrawls a little more difficult to run, however, is the transition between “levels” of material. In a dungeoncrawl, everything is handled at roughly the same level of abstraction: Whether you’re moving between keyed areas or interacting with the content in a keyed area, the actions are described in a consistent (and very specific) way. In a hexcrawl, however, the GM needs to find the effective transition point between “you spend most of the afternoon traveling over the rolling hills east of Maernath” and “you’re fighting orcs; where are you moving in the next ten seconds?”

This is not a massive difficulty, of course, but it does require the GM to develop an additional skill set. Thus it is easy to see the hexcrawl as a natural progression from the dungeoncrawl for the GM: A robust structure using many of the same skills, but also requiring the development of a few new tricks.

Structure, Not Straitjacket: As with the dungeoncrawl, players are given a default action (“pick a direction and go”), but within the hexcrawl scenario structure they’re still free to do pretty much anything their imaginations can concoct.

Flexibility Within the Form: Even moreso than the dungeoncrawl, a GM can put just about anything they want into a hexcrawl scenario structure. (It is, after all, a method for keying an entire world.)

SUMMARIZING THE ‘CRAWL

Looking at the dungeoncrawl and hexcrawl side-by-side, I think we can begin to draw some general conclusions about the ‘crawl structure in general:

(1) It uses a map with keyed locations. (This provides a straight-forward prep structure.)

(2) Characters transition between keyed locations through simple, geographic movement. (This provides a default action and makes it easy to prep robust scenarios.)

(3) The structure includes an exploration-based default goal. (This motivates player engagement with the material and also synchronizes with the geographic-based navigation through the scenario structure.)

In practice, I’ve also found that these ‘crawl structures make it very easy for groups to engage, disengage, and re-engage with the scenario. (You can go into a dungeon, fight stuff for awhile, leave, and when you come back the dungeon will still be there.) This, it turns out, makes them ideal structures for casual play (because players can feel as if they’ve accomplished something even if the dungeon is only half-explored) and open tables (because the disengagement/re-engagement process allows completely different groups of players to interact with the same material).

After considerable thought, I’ve concluded that these latter properties come from:

(A) Material within the scenario structure is firewalled. (In general, area 20 of a dungeon isn’t dependent on area 5.)

(B) The default goal is holographic. (You can explore some of the wilderness or get some of the treasure and still feel like you’ve accomplished something. You can’t half-solve a mystery or execute half a heist and feel the same way.)

(C) The default goal is non-specific. (You can get a bunch of treasure from Dungeon A; then get more treasure from Dungeon B and still be accomplishing your goal of Getting Lots of Treasure.)

(D) The default goal isn’t interdependent. (You can clear the first half of a dungeon and somebody else can clear the second half. In general, you can’t solve the second half of a mystery unless you’ve got the clues from the first half.)

We’ll be coming back to see what we can do with these general principles of the ‘crawl structure, but first I want to turn back to the hexcrawl scenario structure and see what we can build on top of a basic structure.