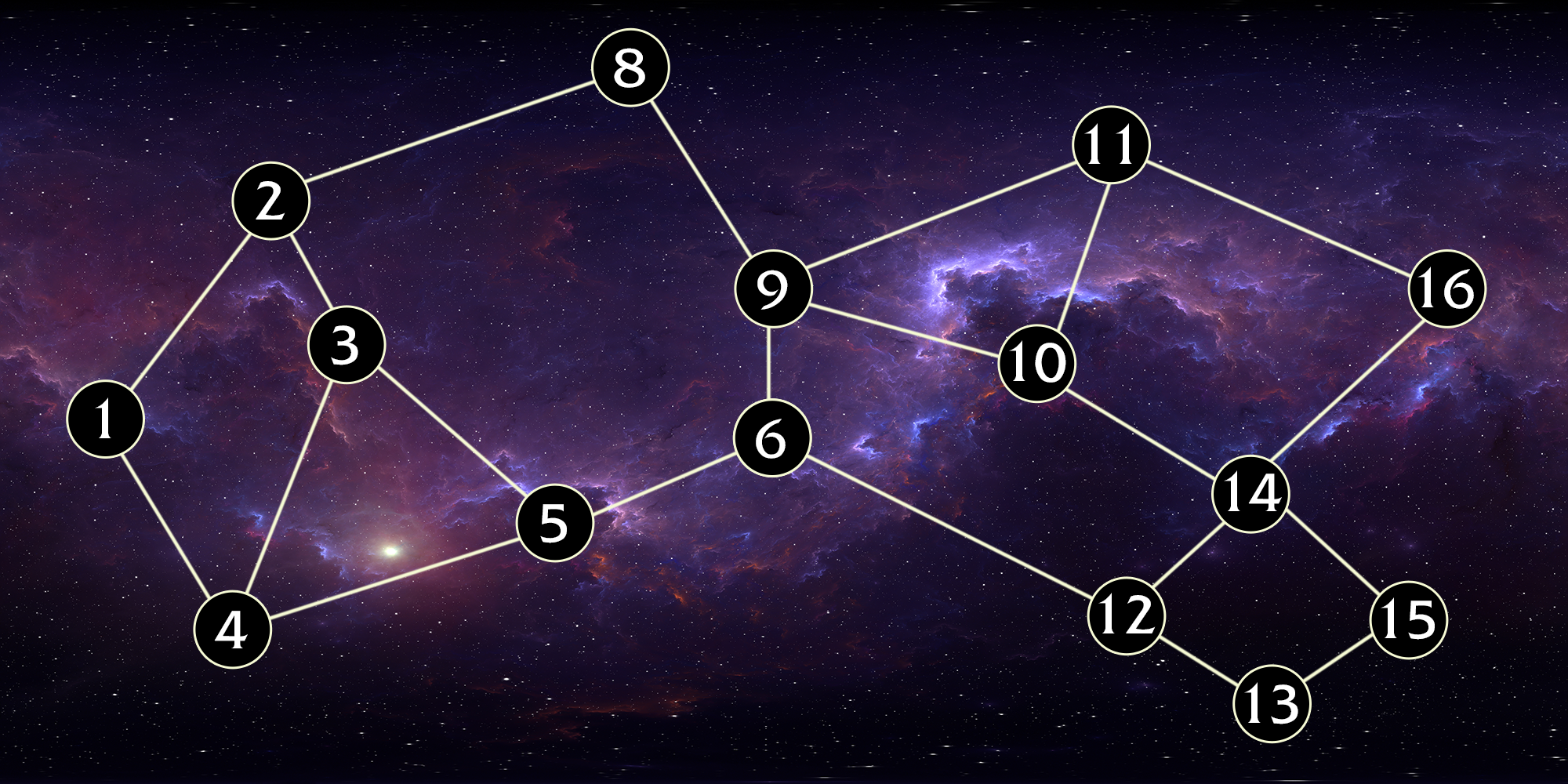

Here are a few advanced pointcrawl techniques you may find useful. Or you can ignore them entirely. Or mix-and-match them. They’re tools. Use the right ones for the job.

Some of them may be more immediately obvious in player-known pointcrawls (where the players can directly invoke them), but they can also be useful for GMs looking to interpret PC actions into a player-unknown pointcrawl.

Some of these advanced procedures include suggested mechanics. For clarity, I’ve chosen to present these as they might be used in a D&D 5th Edition campaign, but they can be easily adapted to other RPGs by simply using the appropriate skills and difficulty numbers for your system of choice.

PATH TYPES

The paths in a pointcrawl can be differentiated by type. Examples might include:

- Roads (including further distinctions between highways/thoroughfares vs. byways/side streets)

- Tracks

- River

- Landmark chain

- Supernatural (portals, fairy paths, etc.)

- Stairs/Shafts

- Mazes

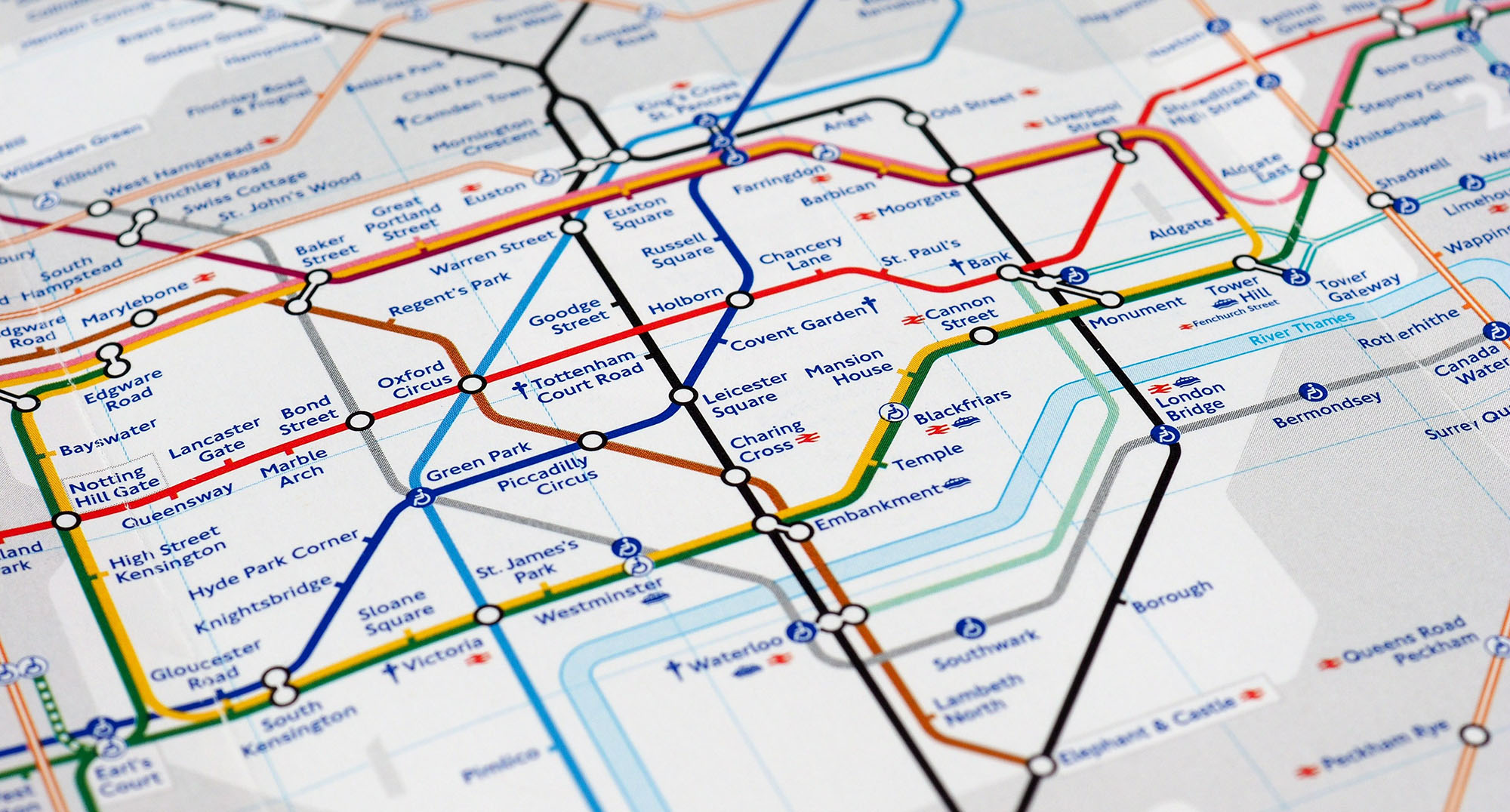

On your pointmap, these types might be indicated by color, line type (dotted, double, etc.), labels, or other iconography. They can be useful for purely descriptive purposes (“you follow the River Wyth as it wends its way through the Forlorn Hills”), but might also be distinguished by:

- Modifying travel time (this could also be done for terrain type)

- Requiring skill checks

- Requiring (or preferring) certain types of vehicles, mounts, or spells

Not every pointmap, of course, needs to feature every single type of path. Think about which paths are most useful and relevant to the pointcrawl you’re designing, and then see if there’s a way that you can make the different types of paths clear and significant.

PARALLEL PATHS: Once you have multiple types of paths in your pointcrawl, it opens the possibility of having two points connected by not just one, but two (or more) paths simultaneously. If you do this, the key thing is to make sure that the paths are distinguished by choice and not just calculation. (For example, if you have two paths and the only difference is that one is faster than the other, the PCs will always take the faster path. Just don’t bother including the other one. On the other hand, if one path is faster but you need to make a skill check to traverse it safely, you now have a meaningful choice in which path to take. Thinking About Wilderness Travel takes a more detailed look at this issue.)

HIDDEN ROUTES

A hidden route in a pointcrawl is simple a connection between two points that is not immediately obvious; i.e., the PCs have to find the route before they can use it. In a wilderness this might be illusory druid paths. In a city it might be linked teleportation circles or perhaps the sewers.

Hidden routes are often discovered as part of a scenario or while exploring a particular location (i.e., you’re looking around the crypts beneath the Cathedral and discover a tunnel heading to the Harbor). In some cases, discovering the hidden route might be as easy as making an Intelligence (Investigation) or Wisdom (Perception) check to find the route.

SHORTCUTS & SIDE ROUTES

The PCs want to move from one point to another without moving through the points between. (For example, they want to go directly to the Trollfens without first passing by the weird red rock. Or they want to go south to the Docks without passing through Shiarra’s Market.) What happens?

In some pointcrawls this might not be possible. (You can’t walk through solid rock.) In a typical wilderness it might require trailblazing (using the procedure below). In a typical, safe city, on the other hand, it usually just means getting off the major thoroughfares and circling around on side streets, and probably just happens automatically.

SIMPLE SIDE ROUTES:

- Determine an appropriate base time. (If they’re trying to go the long way around to bypass something, you can probably set this to whatever the travel time would have been going the normal way. If they’re trying to save time by using an unorthodox shortcut, eyeball the best case scenario.)

- Make a random encounter check.

- Make an appropriate skill check. (This is probably a Wisdom-based check. Perhaps Wisdom (Stealth) if their goal is to avoid attention, or Wisdom (Survival) if they’re trying to cross a trackless waste.)

- If the check is successful, they arrive at their intended location.

- If the check is a failure, then they’re lost and will need to make another check. If they were trying to avoid trouble, the trouble finds them. Either way, they’ll need to repeat the random encounter check and the skill check until they succeed.

TRAILBLAZING

Trailblazing reduces the party’s speed by one-half (adjust the base time of the journey appropriately), but also marks an efficient trail through the wilderness with some form of signs — paint, simple carvings, cloth flags, etc. Once blazed, a trail is effectively added to the pointmap.

Note: If the strata you’re using for your pointcrawl is a wilderness hexcrawl map, you can alternatively use the hexcrawl trailblazing mechanics to create these new trails.

HIDDEN SIGNS: The signs of a trail can be followed by any creature. When blazing a trail, however, the character making the signs can attempt a Wisdom (Stealth) check to disguise them so that they can only be noticed or found with an opposed Wisdom (Perception) or Intelligence (Investigation) check.

You don’t need to make a check to follow your own hidden signs (or the hidden signs of a trail you’ve followed before). Those who are aware of the trail’s existence but who have not followed it before gain advantage on their skill check to follow it.

OPTIONAL RULE – OLD TRAILS: Most trail signs are impermanent and likely to decay over time. There is a 1 in 6 chance per session that a trail will decay from good repair to weather worn; from weather worn to poor repair; or from poor repair to no longer existing.

Someone traveling along a weather worn trail can restore it to good repair as long as they are not traveling at fast pace. Trails in poor repair require someone to travel along them at the trailblazing travel pace to restore it to good repair.

Note: You might use these same guidelines for similar trails on your original pointmap. But it can be assumed that any trails in regular use — whether by the PCs or otherwise — either won’t decay or won’t decay past poor repair.

TRAVEL PACE

You can use D&D 5th Edition travel pace in a pointcrawl fairly easily. I recommend simplifying/fudging the normal travel distances:

- Slow Pace: 1 interval per watch

- Normal Pace: 2 intervals per watch

- Fast Pace: 3 intervals per watch

(You can replace “watch” with whatever timespan is most useful for the pointcrawl.)

ALTERNATIVE 1: Indicate the connection length in standard intervals, but then separately indicate interval duration for normal, slow (¾), and fast (x1.5) travel paces.

You may also want to reduce the chance of a random encounter for fast travel paces. (Slow travel paces would theoretically result in more checks, but in 5th Edition this is usually cancelled out by the reduced encounter chance due to the extra caution being taken.)

ALTERNATIVE 2: Reference the pointcrawl’s strata and calculate the actual distance (and terrain modifiers). Then simply use the standard rules for travel pace to calculate time, making encounter checks per watch. (The disadvantage here is that you’re adding a lot of unnecessary complexity to your pointcrawl procedure.)

ADDENDUM

Depthcrawls