- Treasure.

- It’s where the bad guy we’re trying to stop is hiding out.

- It’s where the bad thing we’re trying to stop is happening.

- It’s where the thing we need has been hidden, lost, or secured.

- It’s between where we are and where we need to be.

Lately I’ve been reflecting on the “nostalgia kids” subgenre of urban fantasy / supernatural horror. It’s epitomized by Stephen King’s It and Hearts in Atlantis, J.J. Abrams’ Super 8, and, of course, the recent sensation of Stranger Things. There are a lot of different elements which make this subgenre work, most of them shared by supernatural coming of age stories in general (e.g., E.T.) — the innocence of the protagonists; their vulnerability and isolation; the supernatural elements as metaphors for both the unseen aspects of a child’s life and also the “secret lore” of the adolescent passage to adulthood; and so forth.

But I think the aspect of the “nostalgia kids” stories which makes them unique and distinct is the contrast between the nostalgia-tinged view of the past and the supernatural abnormality. Most supernatural horror movies, of course, feature a rupturing of our expectations of the real world. But the nostalgic milieu heightens the sense of “rightness” and, thus, the fundamental wrongness of the supernatural element which disrupts our image of a well-remembered yesterday.

Well-told versions of these stories operate even when the reader/viewer is not personally nostalgic for the era in question, because the narrative conveys the nostalgia itself. (This is the case for me with, say, Back to the Future and It, which are soaked in nostalgia for an era I did not personally experience. Conversely, Stranger Things and Ready Player One both conjure forth eras I personally experienced, albeit in very different ways.)

You can see this same fundamental tension between nostalgia and the disruption of memory in the artwork of Simon Stålenhag:

Stålenhag conjures forth a nostaglic image of the ’80s and then disrupts that nostalgia through the presence of giant robots, rusting remnants of colossal technology, and levitating vehicles. You can see how the fantastical elements of these images are heightened by the context of the nostalgic imagery:

If you simply took the image of this giant mecha, for example, it would be pretty cool. But placing it the context of the ’80s police cars lends it a very specific and particular resonance.

RECURSION ERROR

So at some point the designers of the Tales from the Loop thought it would be cool to set a roleplaying game in the world created by Stålenhag’s art.

But there’s a problem. When you take elements of Stålenhag’s art, use them to construct an alternative history of the ’80s, and then say, “this is the world your PCs think of as normal, but there will ALSO be these other elements which are totally weird and supernatural and stuff” you end up with a recursion error: The game wants you to evoke nostalgia and then disrupt it with the fantastic in order to create a very specific mood and emotional response… but then tells you to NOT feel that mood or have that emotion in response to these OTHER fantastical elements. The fundamental dynamic of the “nostalgia kids” genre is disrupted because the game is constantly undercutting the thing which the game is supposedly about.

But there’s a problem. When you take elements of Stålenhag’s art, use them to construct an alternative history of the ’80s, and then say, “this is the world your PCs think of as normal, but there will ALSO be these other elements which are totally weird and supernatural and stuff” you end up with a recursion error: The game wants you to evoke nostalgia and then disrupt it with the fantastic in order to create a very specific mood and emotional response… but then tells you to NOT feel that mood or have that emotion in response to these OTHER fantastical elements. The fundamental dynamic of the “nostalgia kids” genre is disrupted because the game is constantly undercutting the thing which the game is supposedly about.

In actual play, we found that this tended to result in Stålenhag’s elements being minimized or even eliminated during play. But isn’t the entire point of the game to be an RPG about Stålenhag’s art? (I think they might have been better served making a game about those police cars: Embrace the alternate history and make a game about law enforcement needing to deal with the complexities of mecha and robots and hovercraft in the ’80s. But I digress.)

CHARACTERS ARE COOL

What works great, on the other hand, is the character creation system. It generates really rich PCs with very game-able home lives in a surprisingly small amount of time: It is absolutely possible to sit down with a group, walk them through character creation, and have a meaty and significant first session of play all in a single evening.

At the end of character creation, your Kid will be fleshed out with a drive, anchor, problem, pride, favorite song, and significant relationships. And what makes this really work is that the mechanics make these elements immediately meaningful through gameplay. For example, the action of play will generally leave your Kid afflicted with Conditions (like Upset, Scared, Exhausted, and Injured). The only way to deal with these Conditions (before they pile up and overwhelm you) is to either have a meaningful scene of interaction with the other kids (which helps a little) OR to have a meaningful scene of interaction with the adults in your life.

This constant “touching base” with the home life of the character is really essential for the game to sing (and something we’ll be coming back to in a second).

SYSTEM IS BROKEN

Unfortunately, the biggest problem with Tales from the Loop is that the system is broken. Not quite in a “this is terrible and unplayable” way but in a “this is really making for a mediocre experience” kind of way. (It’s like driving a car with a shattered windscreen: The car technically performs its function, but it’s not exactly ideal.)

The key problem is that the success rate for the core mechanic is abysmal. You Kids will generally have about a 40-50% chance of succeeding at a test, and that’s before you get hitched into the death spiral that’s the typical result of failure. (Failure generally applies a Condition; Conditions drastically reduce your chance of success.) It creates an incredibly frustrating experience. And maybe that’s intentional (you’re playing Kids), but it becomes really problematic in a game designed entirely around mystery scenarios with skill tests as the gateways for navigating those mysteries.

As an experienced GM I had a number of ways of routing around these problems, but watching a relatively new GM ram her face into the mechanics and having her scenarios grind to a painful halt over and over again was unpleasant. (And even rerouting around them is, obviously, a needlessly frustrating experience.)

The system is also kind of curiously random in the narrative control it gives to the players. For example, the game features the “description on demand” technique in which the GM randomly asks a player to fill in the details of the world (because, hey, that’s like having narrative control, right?). And it mechanically does stuff like giving players the ability to create NPCs out of whole cloth with whatever skill set and background they want without the GM being able to say anything about it. But then it runs in abject TERROR at the idea of letting players decide what NPCs can be reasonably convinced of and strenuously emphasizes that the GM can veto it.

It also contrasts even more oddly with the book’s raging hard on for railroading. A frequent refrain is, “Are your players not interested in something? Remind them of their Drives AND TELL THEM TO GET WITH THE FUCKING PROGRAM.” (I might have made the subtext into text there.)

UNSTATED ASSUMPTIONS

Contributing to the systemic problems of Tales from the Loop is that the designers seem influenced by games like Apocalypse World, but don’t seem to fully understand what makes Powered by the Apocalypse games tick: They’ve got Principles and a discussion of how mystery scenarios can be constructed… but don’t seem to grok that the reason these things work in PbtA is because they’re mechanically supported RULES. After a great deal of experimentation, I’ve concluded that the game works best if you follow three “best practices” (which are, unfortunately, not clearly called out in the text):

First: Fail Forward Resolution. This makes the abysmal success rates less painful, and the game does include the Conditions mechanic which can be used as a default consequence: You’ll still achieve your goals, but you’re going to pay for it with a physical or emotional condition which you need to deal with.

Second: Narrative Resolution. Partly because this approach lends itself towards fewer checks resolving larger chunks of narrative (which reduces the number of tests and makes the whiff rate of the core mechanic less painful).

Third: Treat the suggested mystery structure as LAW. Most notably, make sure you are consistently alternating between Mystery Scenes and Everyday Life Scenes. When confronted with a mystery scenario, many gamers will dive in and not come up for air until the scenario is resolved. Although, somewhat incoherently, several of the scenarios in the book don’t lend themselves to this style of play, the Conditions mechanics will push you in this direction naturally and we consistently found it was essential to get anything remotely playable out of the system.

CORE SCENARIOS

Speaking of scenarios, I should note that the core rulebook for Tales from the Loop is chock full of scenario material. (It actually takes up a majority of the 196 page book.) This includes four traditional scenarios and a “Mystery Sandbox”.

The latter is interesting because it’s tied into the character creation system: If you use the default character creation options, the resulting PCs will be inundated with scenario hooks for the sandbox. Unfortunately, the actual design of the sandbox mostly consists of scenario ideas that the GM needs to develop into fully playable material. I think this is a misstep: The space spent on the fully-developed scenarios would have been better spent fully-developing the Mystery Sandbox so that GMs could just run it out of the box.

It doesn’t help that the fully-developed scenarios are… questionable. There’s some cool ideas in there, but their continuity, structure, and content will frequently leave you scratching your head. I think my “favorite” moment is the scenario where the Kids are out in the middle of nowhere in the middle of winter, they stumble across a cabin, and the owner of the cabin basically says, “Would you kids like to take my car? Here are the keys. Make sure you don’t scratch it on your way to the next plot point!” Which is really weird.

There are a lot of these types of interactions which will leave you wondering whether the scenario authors have any actual understanding of how adults talk to children.

The setting and scenario material is not helped by the attempt, in the English language edition, to adapt the original setting (a small set of islands in Sweden) to an American alternative (a desert town in Nevada). This localization effort is carried out by placing American names in parentheses after the Swedish originals. For example:

It’s a clever idea. The result, unfortunately, is an abysmal failure. First, the parentheses aren’t consistently executed, resulting in scenarios that are only half-way converted and creating an immense amount of confusion for the GM trying to keep frequently large casts of characters consistent. Second, it turns out that just swapping names isn’t enough to re-contextualize Swedish islands to American desert.

For example, one scenario features the wreck of a Russian mining ship. That makes sense off the coast of a Swedish island. In Lake Mead, however? That demands some sort of explanation… and none is forthcoming.

CONCLUSION

My initial experiences with Tales from the Loop leaned heavily towards the negative… but there was a spark of potential in there that tantalized me and brought me back over and over again to see if I could fan that spark into something greater.

I described the recommended procedures and approach I eventually figured out above. But my overall impression kind of boils down to the core mechanic: The reroll mechanics help. The rules for Helping help. A GM making extensive use of the Extended Trouble mechanics will help. Using narrative resolution techniques helps. But you still end up with a very tenuous bubble, and you’re still running headlong into some very hard limits based on some very limited resource pools that strongly curtail the flexibility of the system.

But even using all of these recommendations, we ultimately found the system to be… meh.

What I’m left with is a game which largely shares the enigma I found in D&D 4th Edition Gamma World: Is a really kick-ass character creation system enough to save an otherwise mediocre and/or broken gaming experience?

For Gamma World, my answer was Maybe… and then I never played it again.

Tales from the Loop seems to be a better game than that, so I will answer: Some times.

And I say that in large part because we found that the strengths of the character creation in Tales from the Loop extended deeper into actual play, resulting in some very emotionally powerful play. I also suspect many will find much greater utility (and even revelatory innovation) in the game’s Mystery Sandbox than I do. (It was certainly refreshing to see such an approach headlined so prominently and centrally in an otherwise mainstream RPG.)

Style: 5

Substance: 3

FURTHER READING

Tales from the Loop: System Cheat Sheet

Tales from the Loop: Nintendo Slugs

It’s time to discuss a topic which is surprisingly contentious: Should the GM tell their players the target number of a skill test?

(Seriously. Go to any online RPG forum, ask this question, and watch the long knives come out nine times out of ten.)

My personal approach to open and hidden difficulty numbers is to consider them a tool rather than an ideology, with their use being a blend of utility and practicality. What information in the game world does the difficulty number represent and does the character have access to that information?

When in doubt, I will generally default to not telling the players the target number. But this default position can be flipped in some systems for reasons of practicality. For example, in Call of Cthulhu you apply difficulty to the character’s skill rating and then attempt to roll under the modified rating. I’ve found it’s generally easier to give the players the difficulty modifier and have them simply report their success or failure rather than getting them to report a margin of success that I can then compare to the difficulty rating. (Your mileage may vary here, obviously.)

In addition to simple practicality and efficiency in game play, my method is influenced by a couple of factors. First, there is a limited bandwidth by which the players perceive the game world compared to their characters: They are relying almost entirely on imprecise verbal descriptions, whereas their characters have access to their full panoply of sensory input. While it is true that their characters cannot necessarily measure their chance for success at a task with mathematical certainty, I find that this nevertheless achieves more associated results than characters, for example, leaping over crevasses that no sane person would attempt if they could actually see it with their own eyes. Open difficulty numbers reduce the frequency with which there is miscommunication between the GM and the players, which can help minimize the old Are you sure you want to do that? problem.

Second, there are many circumstances in which the players will be able to figure out what the target number is. (Multiple characters making attacks against a fixed armor class, for example.) In some cases this experience can be very immersive (as the characters slowly figure out just how skilled their dueling partner is before declaring that they’re not actually left-handed, for example). But that also makes it an example of how knowing a difficulty number doesn’t instantly implode the table’s immersion, and even in circumstances where difficulty numbers are initially hidden, it can often make sense to explicitly lift the veil of mechanical secrecy after a short period of time in order to facilitate the practicality of speeding up play.

RESOURCE SPEND GAMES

Over the last decade or so we’ve seen a proliferation of RPGs featuring mechanics where the players will spend points from a limited pool as part of a skill test. GUMSHOE and the Cypher System offer one common form, with points being spent from skill or attribute pools in order to provide a bonus to the skill test. Tales from the Loop offers another variety, featuring a variety of resource pools which can be spent to reroll failed checks.

provide a bonus to the skill test. Tales from the Loop offers another variety, featuring a variety of resource pools which can be spent to reroll failed checks.

I’ve found that these types of systems — particularly the GUMSHOE and Cypher System variety — require some special attention when it comes to open vs. hidden difficulty numbers. Blindly spending limited resources on tasks with unclear difficulties generally doesn’t seem to work well in these types of systems: Players often get frustrated and resources are generally overspent, which can rapidly propel a session towards the hard limits of the system and really limit effective scenario design.

Which is not to say, of course, that difficulty numbers should NEVER be unknown in such games. The occasional spice of an unknown search test, for example, can be really rewarding: The player doesn’t know if there’s anything hidden in the room or how valuable it may be, so they have to make a tough choice about exactly how much effort they’re going to put into searching it. When facing a previously unknown creature, they have to make a choice about snapping off a shot or really taking the effort to aim. That’s immersive and effective.

But if the whole game is cloaked in perpetual mystery, it’s much less effective in practice. It muddies decision-making (particularly in these resource spend games) and hurts immersion.

Another way of looking at this is that there is a “threshold of knowledge” at which the GM deems it appropriate to reveal the difficulty number. This threshold, however, is basically a slider. What I’m suggesting is that for these resource spend mechanics you want to radically reduce your threshold (particularly if you normally keep it relatively high).

For these resource spend games I have also coined the term “routine check” so that I can still call for things like routine Perception tests to determine which character spots something first without having everyone burn away their resource points, uh… pointlessly.

UNCERTAIN TASKS

Traveller 2300 included an interesting resolution method that I have never seen reproduced elsewhere, but which can be trivially adapted to virtually any RPG system. For any uncertain task, in which the actual success or failure of the outcome may not be immediately clear to the character (such as gathering information, convincing someone to help you break the law, or repairing a buggy piece of equipment):

… both the player and the referee roll for success (the referee rolls secretly). If both are unsuccessful, the referee provides no truth. If one is successful and the other is unsuccessful, the referee provides some truth. If both are successful, the referee provides total truth. In all cases, the referee does not indicate whether the answer or information provided is truth, some truth, or total truth.

A result of no truth means the character is totally misled as to the success of the attempt. Completely false information is given.

A result of some truth means the character is given some idea of the success of the attempt. Some valid information is given.

A result of total truth means the character is not misled in any way as to the success of the attempt. Totally correct information is given.

Because of the hidden nature of the referee’s throw, the character cannot know for certain the nature of the information being obtained. A referee may find characters doubting total truth, accepting some of no truth, or accepting all of some truth.

Marc Miller, the leader designer for Traveller: 2300, wrote about this mechanic in “Traveller: 2300 Designer’s Notes” in Challenge Magazine #27:

Setting fuses for demolitions is an uncertain task contained in the Traveller: 2300 rules. It is classified as easy, and anyone with any skill will usually succeed. Once in a while, the referee will roll a failure while the player succeeds: somehow the fuse setting failed (although it looks OK) and the explosive won’t detonate when the proper time comes. And once in a while, the player will roll a failure (and immediately realize that he has wired the explosive wrong), he can rewire them immediately to try to fix the fault. And sometimes, the player will roll a failure and hear the referee tell him the charges have exploded – because the referee also rolled a failure.

This method is an incredibly clever way of reintroducing uncertainty into the player’s (and character’s) perceptions even when embracing the practical advantages of player rolls and open difficulty numbers. I think it deserves to be much more widely known and used.

As a result of long tradition, most mechanical resolution in roleplaying games takes the form of action resolution. There is, however, an alternative paradigm that you may find useful: narrative resolution.

As a result of long tradition, most mechanical resolution in roleplaying games takes the form of action resolution. There is, however, an alternative paradigm that you may find useful: narrative resolution.

The classic example for distinguishing between the two involves the PCs trying to find hidden documents in an office with a locked safe. With action resolution, the mechanics determine whether or not they can crack the safe. With narrative resolution, the mechanics determine whether or not they find the documents. (The distinction, it should be noted, doesn’t necessarily require a different set of mechanics: Either attempt can boil down, mechanically speaking, to the exact same Lockpicking check. The difference is in how you set up the stakes for the test and in how you interpret the results of the test.)

With action resolution, the player declares “I want to do Y” with the expectation or hope that it will result in X being accomplished.

With narrative resolution, the player declares “I would like to accomplish X by doing Y”.

There are advantages and disadvantages to both approaches.

With narrative resolution, being able to say “this is how I would like to solve this problem” allows players to control their spotlight and it allows the GM to take a more general approach to prep. (The GM knows that there is incriminating evidence to be found in the club. The players decide whether they want to get it by sneaking into the office and cracking the safe, seducing the lounge singer, interrogating the club owner, or putting the place under surveillance.)

On the other hand, action resolution typically allows for a more simulationist experience of the game world (which, in its verisimilitude, can be more immersive for many). And it also allows for a more diverse array of possible outcomes (which can prevent the game from becoming predictable). (For example, the PCs succeed at opening the safe, but instead of finding the incriminating evidence of a criminal enterprise they find the mob’s blackmail photos of JFK schtupping Marilyn Monroe. Now what do they do?)

USING NARRATIVE RESOLUTION

Unsurprisingly, narrative resolution is often conducive to (and associated with) storytelling games and RPGs with a dramatist focus. But this isn’t necessarily the case: Remember that undetermined external factors are usually factored into mechanical resolution. There’s no reason that one of those undetermined external factors can’t be whether or not the documents the PCs are looking for are in the safe. The GM is simply saying, “I don’t know whether or not there’s incriminating documents in there; let’s ask the game mechanics and find out together.” (This may require a radical shift in your thinking — it’s literally a different paradigm for interpreting mechanical results — but it’s no less valid.)

Oddly, narrative resolution often combines well with failing forward. I say oddly because it seems counterintuitive that a system predicated on determining whether or not your goal succeeds would pair well with a technique predicated on assuming that your goal fails (albeit with complications). But I think it works because, first, narrative resolution is focused on the goal, and that focus makes it more natural for failing forward (which also focuses on the goal) to come into play. Narrative resolution also tends to lend itself well to larger chunks of resolution, which opens up a lot more breathing space for the sorts of interesting complications which really make failing forward worthwhile.

COMMON CONFUSIONS

When trying to grok the distinction between narrative resolution and action resolution, there are a couple common ways that I’ve seen people get confused.

First, it’s not unusual for those being introduced to the concept of narrative resolution to frame a mechanical resolution in such a way that the desired goal of the PCs is identical to the action resolution and then claim that there is in, fact, no difference between the two.

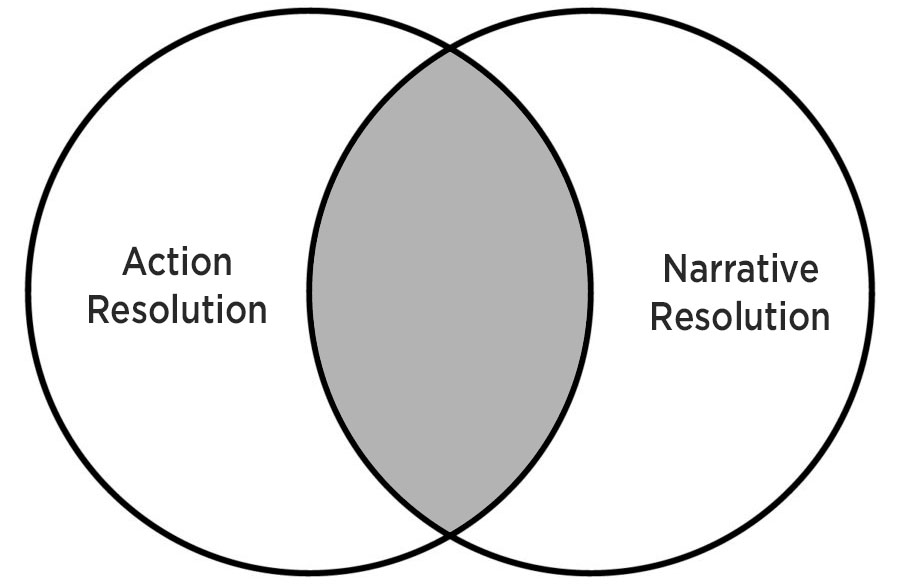

For example, you might set up a scenario where the player says, “I want to sneak over and grab the guard’s keys.” The action is to sneak over and grab the keys; the desired outcome is to sneak over and grab the keys. So, what’s the difference? Well, in this case, there is none. The two techniques resemble a Venn diagram in this regard.

Second, it’s oddly not unusual for those trying to explain the concept of narrative resolution to claim that traditional combat mechanics are a form of narrative resolution mechanic. The argument is that “make that person dead” is the desired narrative outcome and, therefore, the combat mechanics provide a narrative resolution of that outcome.

This is actually just the same error from a different angle, though. “HP 0 = DEAD” isn’t a narrative resolution mechanic. It’s just telling you whether or not you’ve killed somebody (just like an attack roll tells you whether or not you’ve hit someone with your sword). By setting the narrative goal to be “kill that guy”, you once again superficially make the action resolution look like narrative resolution.

What would a narrative resolution mechanic look like? Well, it would be “HP 0 = you accomplished whatever you goal was”. Was it to escape? Was it to convince the princess that you’re a better swordsman? Was it to impress your master? Was it to kill somebody?

A FEW FINAL ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This concept – including the classic safecracking example – was pioneered by D. Vincent Baker using the terms “task resolution” and “conflict resolution”. Those terms have become relatively popularized and many of my readers may be wondering why I’ve chosen to swap them out for the terms “action resolution” and “narrative resolution”.

Basically, having participated in several dozen discussions about this topic over the last decade or so, I have found that the terms “task resolution” and “conflict resolution” are a source of deep and consistent confusion.

First, the common definition and usage of the term “task” is frequently goal-oriented: You are assigned a task and then determine how you are going to accomplish that task. This seems to heavily contribute to the first point of confusion described above (where people can’t distinguish what the difference is supposed to be between the task-oriented and goal-oriented resolution methods).

Second, the term “conflict resolution” only makes sense within a very specific and adversarial understanding of the interaction between the GM and the players. If you look at the lump sum of Baker’s thoughts back in 2004 (when he was struggling with and exploring the implications of this relationship), it makes a lot of sense why he chose the term “conflict”. But outside of that specific context, it tends to lend itself to the second point of confusion discussed above. I’ve also seen it frequently lead people astray who then believe that “conflict resolution” only applies if an NPC is opposing the PC (either directly or indirectly).

I don’t really consider it likely that my revised terminology will have widespread adoption at this point, but that’s not my primary concern: My primary concern is to attempt to clearly communicate a useful set of concepts to those reading this essay.

Awhile back I was having an online discussion with someone who was struggling to make a Pokémon-based hexcrawl interesting. He found himself facing “a bunch of really boring hexes” and couldn’t figure out how to make them interesting.

The key element of the hexcrawl structure is that of exploration. It becomes kind of pointless if all you’re doing is moving between civilized locations. It works best if you’re out on an untamed frontier or in a point-of-lights setting where the known settlements are separated by vast zones of mystery.

There are a couple things that makes a hexcrawl easier to stock in a D&D-esque fantasy setting:

I’m not a deeply committed Pokemon fan (I’ve watched a few episodes of the TV show; I’ve played a couple games). But from what I remember of the game, it featured a lot of little tiny villages and you traveled through distinct wildernesses to get from one village to the next. The focus was primarily on civilization, but it wouldn’t take a whole lot to emphasize the wilderness which surrounds them. So there’s your point-of-lights element.

You can start adding depth by looking at the random Pokemon encounters in the wild and breathing life into your wandering monsters. Give them lairs, relationships, etc.

Re: Ancient civilizations. I remember that Pokemon has stuff like fossils and the mystery of the GS ball from the anime. Those are the seeds I’d pursue and develop into something more rich, robust, and varied. (The Pokemon lore already contains a lot of “legacies lost to history”; there’s no reason you can’t add to that lore.)

Re: New World Syndrome. I seem to recall lots of stuff in the Pokemon lore which suggests some Pokemon are a lot more intelligent than just “animals that can be captured to fight each other”. I’d explore that. I’d also look at Mewtwo’s original back story (created in a laboratory in the middle of the wilderness) and run with that basic idea — strange Pokemon cults and Pokemon research labs hidden out on the frontiers.

Also: Do some googling on the “Pokemon is post-apocalyptic” fan theories.

Finally, if you’re looking for inspiration, pull up lists of Pokemon episodes and use them as brainstorming seeds. Going through that link, for example, I immediately pull out or interpolate:

And so forth.