It’s time to discuss a topic which is surprisingly contentious: Should the GM tell their players the target number of a skill test?

(Seriously. Go to any online RPG forum, ask this question, and watch the long knives come out nine times out of ten.)

My personal approach to open and hidden difficulty numbers is to consider them a tool rather than an ideology, with their use being a blend of utility and practicality. What information in the game world does the difficulty number represent and does the character have access to that information?

- If the difficulty number represents something that the PCs can directly observe, tell the players the target number of the check. (An easy example would be the difficulty of jumping over a crevasse: The character can actually see the crevasse and make a pretty good guess about how difficult it is. Telling the player helps give them a clarity similar to their character’s vision.)

- If the difficulty number represents something that the PCs can’t observe, keep the number hidden from them. (For example, they’re walking through a jungle and I want to know if they spot a tribesmen hiding in the canopy above them. The difficulty of the spot task is based on how good the tribesmen are at hiding. Does the PC know how good the tribesmen are at hiding? No. They don’t even know it’s tribesmen they’re trying to spot. Therefore, they don’t get the target number.)

- If you’re feeling tricksy, you can give the players an estimated difficulty number based on what their PC does know and only reveal the real difficulty number when they’ve realized their error. (“The guy is standing nude in the middle of the field. Should be really, really easy to hit him…” “Your shot bounces off the force field surrounding him. This might be trickier than you thought.”)

When in doubt, I will generally default to not telling the players the target number. But this default position can be flipped in some systems for reasons of practicality. For example, in Call of Cthulhu you apply difficulty to the character’s skill rating and then attempt to roll under the modified rating. I’ve found it’s generally easier to give the players the difficulty modifier and have them simply report their success or failure rather than getting them to report a margin of success that I can then compare to the difficulty rating. (Your mileage may vary here, obviously.)

In addition to simple practicality and efficiency in game play, my method is influenced by a couple of factors. First, there is a limited bandwidth by which the players perceive the game world compared to their characters: They are relying almost entirely on imprecise verbal descriptions, whereas their characters have access to their full panoply of sensory input. While it is true that their characters cannot necessarily measure their chance for success at a task with mathematical certainty, I find that this nevertheless achieves more associated results than characters, for example, leaping over crevasses that no sane person would attempt if they could actually see it with their own eyes. Open difficulty numbers reduce the frequency with which there is miscommunication between the GM and the players, which can help minimize the old Are you sure you want to do that? problem.

Second, there are many circumstances in which the players will be able to figure out what the target number is. (Multiple characters making attacks against a fixed armor class, for example.) In some cases this experience can be very immersive (as the characters slowly figure out just how skilled their dueling partner is before declaring that they’re not actually left-handed, for example). But that also makes it an example of how knowing a difficulty number doesn’t instantly implode the table’s immersion, and even in circumstances where difficulty numbers are initially hidden, it can often make sense to explicitly lift the veil of mechanical secrecy after a short period of time in order to facilitate the practicality of speeding up play.

RESOURCE SPEND GAMES

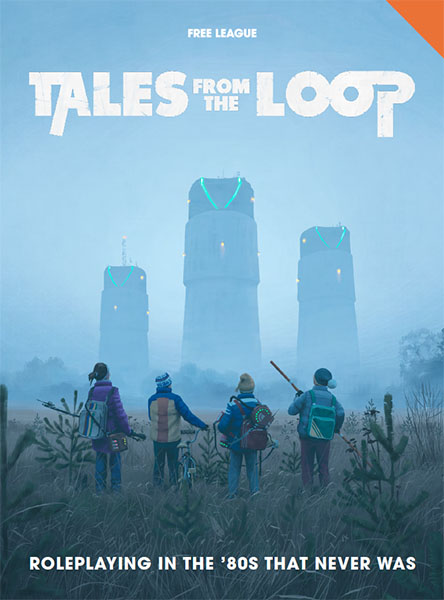

Over the last decade or so we’ve seen a proliferation of RPGs featuring mechanics where the players will spend points from a limited pool as part of a skill test. GUMSHOE and the Cypher System offer one common form, with points being spent from skill or attribute pools in order to provide a bonus to the skill test. Tales from the Loop offers another variety, featuring a variety of resource pools which can be spent to reroll failed checks.

provide a bonus to the skill test. Tales from the Loop offers another variety, featuring a variety of resource pools which can be spent to reroll failed checks.

I’ve found that these types of systems — particularly the GUMSHOE and Cypher System variety — require some special attention when it comes to open vs. hidden difficulty numbers. Blindly spending limited resources on tasks with unclear difficulties generally doesn’t seem to work well in these types of systems: Players often get frustrated and resources are generally overspent, which can rapidly propel a session towards the hard limits of the system and really limit effective scenario design.

Which is not to say, of course, that difficulty numbers should NEVER be unknown in such games. The occasional spice of an unknown search test, for example, can be really rewarding: The player doesn’t know if there’s anything hidden in the room or how valuable it may be, so they have to make a tough choice about exactly how much effort they’re going to put into searching it. When facing a previously unknown creature, they have to make a choice about snapping off a shot or really taking the effort to aim. That’s immersive and effective.

But if the whole game is cloaked in perpetual mystery, it’s much less effective in practice. It muddies decision-making (particularly in these resource spend games) and hurts immersion.

Another way of looking at this is that there is a “threshold of knowledge” at which the GM deems it appropriate to reveal the difficulty number. This threshold, however, is basically a slider. What I’m suggesting is that for these resource spend mechanics you want to radically reduce your threshold (particularly if you normally keep it relatively high).

For these resource spend games I have also coined the term “routine check” so that I can still call for things like routine Perception tests to determine which character spots something first without having everyone burn away their resource points, uh… pointlessly.

UNCERTAIN TASKS

Traveller 2300 included an interesting resolution method that I have never seen reproduced elsewhere, but which can be trivially adapted to virtually any RPG system. For any uncertain task, in which the actual success or failure of the outcome may not be immediately clear to the character (such as gathering information, convincing someone to help you break the law, or repairing a buggy piece of equipment):

… both the player and the referee roll for success (the referee rolls secretly). If both are unsuccessful, the referee provides no truth. If one is successful and the other is unsuccessful, the referee provides some truth. If both are successful, the referee provides total truth. In all cases, the referee does not indicate whether the answer or information provided is truth, some truth, or total truth.

A result of no truth means the character is totally misled as to the success of the attempt. Completely false information is given.

A result of some truth means the character is given some idea of the success of the attempt. Some valid information is given.

A result of total truth means the character is not misled in any way as to the success of the attempt. Totally correct information is given.

Because of the hidden nature of the referee’s throw, the character cannot know for certain the nature of the information being obtained. A referee may find characters doubting total truth, accepting some of no truth, or accepting all of some truth.

Marc Miller, the leader designer for Traveller: 2300, wrote about this mechanic in “Traveller: 2300 Designer’s Notes” in Challenge Magazine #27:

Setting fuses for demolitions is an uncertain task contained in the Traveller: 2300 rules. It is classified as easy, and anyone with any skill will usually succeed. Once in a while, the referee will roll a failure while the player succeeds: somehow the fuse setting failed (although it looks OK) and the explosive won’t detonate when the proper time comes. And once in a while, the player will roll a failure (and immediately realize that he has wired the explosive wrong), he can rewire them immediately to try to fix the fault. And sometimes, the player will roll a failure and hear the referee tell him the charges have exploded – because the referee also rolled a failure.

This method is an incredibly clever way of reintroducing uncertainty into the player’s (and character’s) perceptions even when embracing the practical advantages of player rolls and open difficulty numbers. I think it deserves to be much more widely known and used.

This discussion would benefit from covering related topic which is hiding the *purpose* of the roll, like in your example with a tribesman hiding in the jungle. While this situation could be resolved by an infamous “Gimme a Notice/Perception roll” I don’t think it is fair. If the effect of the roll is immediate, e.g. tribesman is waiting in an ambush or a party is close to falling into a trap, call for a test should state that openly (“Test Notice to check if you get ambushed by a local tribe”). There is nothing to be gained by obscuring the meaning of such test, it will became obvious right away. If the effect of the roll won’t manifest itself that quickly the players also shouldn’t be left in complete darkness. While “Roll to check if you notice a tribesman watching you” may tell too much (though some would argue that players should differentiate player/character knowledge) something in fashion of “Roll to notice something odd around you” seems to be a fair compromise.

This is even more important than plain difficulty hiding if the system gives the players an option to fudge dice rolls (like re-rolls provided by Savage Worlds’ Bennies).

When it comes to the enigmatic “Gimme a Notice roll”, one of the most irritating things is when GM calls for such test in totally unimportant situations to further confuse players, so they don’t associate each such test with danger (which they do anyway)…

“There is nothing to be gained by obscuring the meaning of such test…”

Of course there is: Presenting only information known by the character allows the player to experience the game world from the perspective of their character.

I’d actually flip the question: What possible benefit is there in telling the players what the Notice check is for? Do you do this with other checks? If they search a room do you tell them that there’s a secret door even if they fail the check? And, if so, why?

“…one of the most irritating things is when GM calls for such test in totally unimportant situations to further confuse players.”

You’re really going to dislike the next entry in this series.

When I first read this in the pre-release on Patreon I was reminded of the technique for uncertain tasks that I have been using for Traveller ever since 2300 came out. I was prompted to write it up at RPG Geek: https://www.rpggeek.com/article/26439016

The idea is that you keep the skill check mechanism exactly the same but one of the check dice is rolled by the game master and kept hidden from the player. The player has to estimate their success based on the information available.

To my mind this is a strongly associated mechanism. The character has performed a task and has some level of confidence in how they did, in some cases they are sure, in others not so much. The player has the dice roll information that is available to them and they are in precisely the same knowledge position as their character, without the GM saying anything.

Consider a completely hidden roll by the GM. The player may know the target number and can estimate the odds of success, but the dice roll provides them with no further information. This would be used in situations where the character really cannot know how things went and they just have to suck it and see.

With hidden target numbers the character does not know the odds beforehand but the dice roll does give the player some extra information about how well the task was done. They just don’t know if that was good enough. It leaves them in a similar position to the secret dice roll in that they don’t know how things really went.

I think both a fully secret roll and a hidden target number gets into weird territory. I haven’t found a use for it.

> “There is nothing to be gained by obscuring the meaning of such test…”

> Of course there is: Presenting only information known by the character allows the >player to experience the game world from the perspective of their character.

You took my quote out of context. I wrote that obscuring is pointless “If the effect of the roll is immediate”. When the character is attempting to open a trapped door, walks into an ambush, someone lobs a grenade at her – the result of the roll goes into effect immediately, hiding the information for few seconds makes no sense to me. On the contrary, information passed alongside the call to make a roll makes huge difference when the player has means to influence its outcome (like some way to get a re-roll or modifier). It also makes the roll much more meaningful to the player, increases the tension. This is not “some Notice roll”, which often means nothing (if GM introduces such random rolls to confuse the players), this is the roll which can put the character in danger. Summarising: hidden intent in this case has no benefits, open intent introduces tension and works fine with meta-game roll-influencing mechanics.

I agree that if the effect of the failed roll won’t manifest itself immediately hiding the roll intent may bring some benefits. On the other hand the players already have a lot of information which the characters shouldn’t know and I find the ability to filter-out such information to be a must for a good player. Hiding also doesn’t work with roll-fudging mechanics (player needs some information to make a good decision about using it). For those reasons I propose a compromise. I agree that “Gimme a Notice roll to check if you see that Bob, the right hand of the Thief’s Guild boss, is following you” does give too much information. How about “you look behind and have an impression that some guy behaves strangely, gimme a Notice roll”. In some cases even very open “Gimme a Notice roll to see if someone is following you” would work fine for me. It’s situational.

Answering the rest of your questions: I have old habits of obscuring as much information from the players as possible but I’m struggling 😉 Yes, I try to be be as descriptive as possible (both in the intent and difficulty level) in most rolls, not only Notice checks. Search is a bit different than Notice, as this is an active check, not one triggered by the situation. The problem we are discussing is not really present here as the roll intent is clear: “roll Search to check what do you find in the room”. Answering the rest: I won’t tell them that there is a secret door in the room but if the roll wasn’t good enough for them to find it I may hint what difficulty number they need to find “something else” and ask if they want to spend a Benny and get a re-roll.

My point of view is probably heavily influenced by the fact that Savage Worlds is my system of choice (Bennies) and that I prefer the “lazy GM”, “plotless” approach (not there yet, but again, struggling with habits 😉 ).

> You’re really going to dislike the next entry in this series.

I tend to enjoy reading your blog even if I disagree with some posts. It is always nice to get to know a different perspective. I find your blog to be the one of the finest on the topic, if you’ll excuse me the flattery 🙂

I always feel the best way is to actually get the players to activate the search not the GM. So for this you would describe the jungle in such a way to get their suspicions up so they say “Can I search around” failure just shows the tension in the fiction, they probably know something is there bit have no idea what or what they are going to do.

I know it seems to be the same thing but I agree with @zgreg in that if the GM says to do it, it gives the game away a little bit to much so instead of tension its kind of annoyance. Its basically “We’ve been to 5 jungles and only now is the GM asking us for a search, I wonder why…”

[…] is a new article about Art of Rulings 12 – Hidden vs. Open Difficulty Numbers by Justin Alexander. The series is excellent but requires some time to […]

I understand that the Traveller 2330 part about “uncertain tasks” also implies, by definition, that target numbers are not known. Because if I, as a player, do know that the success probability is 10%, I also know if I passed or not. Thus if I passed, I know that 10% of the time, the DM will give full truth, 90% of time will be partial. And if I didn’t pass, then 90% of time will be partial, 10% will be utter lie. So I will logically distrust, on principle.

But even if the target number were not known (and supposing that the mechanical design of the game doesn’t allow me to partially deduce it from the roll) that’s no better than pure GM fiat. Equivalent, in all aspects, to a fully hidden roll. I say to try, the DM says something, and I don’t really know if I did well. You really didn’t need a second roll for this.

A third option is that at least I know the target number, but the roll is hidden. Then, for a 10% probability of success, at least I know that 1% of the time the DM will give full truth, 9% of time will give partial truth, and 90% of time will lie. Which means I won’t trust a word she says. In fact, I won’t trust a word until “full truth” probability rises above 50% (which happens at 71% success probability)

Plus, you can’t really apply this to binary, yes-or-no, success-or-failure situations.

I really don’t understand how this mechanic could be useful. What does it offer than the open/hidden rolls doesn’t?

I have always liked this rule and I suggested it on rpg.stackexchange, too (see: https://rpg.stackexchange.com/a/4226/131) even if I now find out I was wrong about where it appeared first.

@Scarbrow: Traveller 2300’s uncertain tasks work with either open or hidden target numbers.

I’m unclear on why you equate “pure GM fiat” with hidden difficulty numbers. Or rather, it’s unclear which term you’re not familiar with.

Your claim that this is equivalent to a hidden difficulty roll is also puzzling. A hidden difficulty roll leaves the player in a single state: Uncertain whether they succeeded or failed. An uncertain task, on the other hand, has two possible states and (if the difficulty is open) the player knows which one they are in: They are either no truth/some truth or some truth/all truth. That’s very different. (In the case where you’re using hidden difficulty numbers with an uncertain task, the player can only SUSPECT which state they are in based on the quality of their roll.)

Credit-Where-Credit’s-Due Department: The (brilliant) uncertain task mechanism was originally developed by Gary Thomas and Joe Fugate of Digest Group, who’re credited for the task system in Traveller: 2300. (It was also used in 1987’s MegaTraveller.)

Another take on the “hidden mirror roll” method:

Both the player and the GM makes a a roll with a die of the same size. If there is a match, the correct information is revealed. The player, however, will not know whether they rolled good or bad, as it’s just an unranked number, so they won’t know whether the information is correct.

This can be extended to include a relevant skill, for example if a player rolls a 3 and has skill +1, the he’ll match with 2,3 and 4 on the GMs die, making it more likely to get a match and the right informatoin.

It can also be extended to include false information: the GM rolls a differently colored die for every piece of information, false or otherwise, they might want to give, and then incorporates any matching dice’s information in the answer.

I got confused reading the section of this article on 2300’s Uncertain Tasks because both this article and the quoted one aren’t actually describing 2300’s rules for Uncertain Tasks.

Page 40 of the Director’s Guide describes Uncertain Tasks as involving the player and GM making their rolls, the GM secretly averaging the results and then using this average to determine success. On a success, the player succeeds and is told accurate information. On a failure, the player fails and is told increasingly wrong information based on the margin of failure.

Page 54 of the Director’s Guide describes setting a fuse as a special case for Uncertain Tasks where results are not averaged and instead result in success, partial success or failure. Also, this task isn’t concerned with the ‘truth’ of information communicated by the GM to the player. Success arms the explosives, partial success results in a dud, and failure results in blowing off your legs with your own claymore.

Looking at Miller’s complete quotation (available online) he seems to describe all Uncertain Tasks as being mechanically treated as resulting in one of three outcomes when this isn’t the case. He does accurately describe the results the fuse-setting rules have on setting fuses, but everything he describes is the result of the emergent behaviour of this system. Given that Uncertain Task outcomes are described here in terms of the ‘truth’-iness of the information the GM gives the player, an example where there is no need for the GM to communicate ambiguous information to the player is irrelevant.

All of that untangling aside, I think it’s important to note that all methods of ruling Uncertain Tasks described here also alter the chance of success – they favour average results over extreme ones. I think it’s natural for a GM to want to get an existing check and make it Uncertain, but they cannot do that using the method described here without making easy checks easier and hard checks harder. The RPGGeek article Dan Dare links in his comment introduces Uncertain checks in a system where all rolls are already made with multiple dice, meaning obscuring one or more of them doesn’t influence the outcome of the check. In systems where outcomes are determined by the result of single dice this isn’t possible.

Since what this ultimately comes down to is providing a range over which uncertainty exists, I think a suitable solution would be as follows:

You will modify your player’s roll with an Uncertainty Dice. Uncertainty Die have an odd number of sides, and whose average value is 0. For example, a d5 Uncertainty Dice’s sides read -2, -1, 0, +1 and +2. Note that you can make such a die by rolling a d6, subtracting 3 from the result, and rerolling 6’s. If an Uncertainty Dice would modify a dice above or below its maximum or minimum value, it does nothing (an 18 +3 is treated as an 18).

Your player knows the target number, the result of their dice, and the range of your Uncertainty Dice, but not the result you secretly rolled. Success and failure are described to the player based on the true result of the dice, but without telling them what that is.

Example: Lesley is rolling a d20 to plant an explosive (no modifier). Anything below a 2 will result in the device exploding immediately, but a 5 or higher will arm it successfully. The GM adds a d9 Uncertainty Die to the roll. Lesley rolls an 8. Lesley knows the bomb didn’t explode before the GM tells them, because their roll cannot be reduced as low as 1, but it can be reduced to a 4, which is a failure. Lesley registers that this means there’s a 1/9 chance the bomb hasn’t successfully armed.

This method maintains an equal probability that any given value on your dice gets rolled while still introducing a controlled amount of uncertainty. Players can still make judgements about how hard a check will be before attempting it (unlike with a hidden DC), the GM has control over the range of uncertainty involved, and it provides a result which can be easily interpreted as a binary success/failure as well as a margin of failure in a check with a gradient of outcomes (such as gossip which might contain a gradient of truth).

@Jinan: In 1986, GDW published Traveller 2300 in a boxed set including a Player Manual and Referee’s Manual.

In 1988, GDW published a second edition of the game as 2300 AD with an Adventurer’s Guide and Director’s Guide.

So the reason you’re confused is because you’re looking at a different edition of the game.

I don’t own the 2300 AD version of the game, but from what you’re describing it certainly sounds like someone broke the uncertain check mechanic.

The RPGGeek article Dan Dare links in his comment introduces Uncertain checks in a system where all rolls are already made with multiple dice, meaning obscuring one or more of them doesn’t influence the outcome of the check. In systems where outcomes are determined by the result of single dice this isn’t possible.

Note that in the Traveller 2300 mechanic, the GM’s check does not affect whether the check is a success or not; it only affects the accuracy of the GM’s description of the outcome.

@Justin: That’s what it was! I suspected I probably hadn’t found an error in both the Alexandrian and the original designer’s description of a TRPG published before I was born but every resource I could find on the issue pointed that way. And here I was feeling all smug for checking the rulebook.

For what it’s worth, I do still think following this description of the Uncertainty system with the example of setting fuses is misleading, since the GM’s roll can influence the success of the check (not just the truth of the GM’s narration), and this is evident when Miller describes the player exploding when they and the GM both fail their roll. I think this might have been what tripped me up and convinced me the GM’s roll mustn’t only influence the accuracy of their narration. Or perhaps that’s just my fault for reading too closely into it!