PREPPING PUBLISHED DUNGEONS

The Art of the Key discusses best practices for writing dungeon keys that are efficient, clear, and easy-to-use at the table.

Many published adventures fall short of that ideal, but I usually won’t waste a lot of time bringing them up to code, so to speak. I find it more effective to occasionally make note of particularly crucial details that are essential to the adventure but buried in the middle of a paragraph, to make sure they don’t get missed during play.

Only in circumstances where an area is particularly baffling will I endeavor to reorganize or redesign the description in my prep notes. (And this often crosses over into remixing the adventure, which remains a topic for another time.)

One thing I will do, though, is pay attention to my personal hierarchy of reference: If the adventure is referencing a particular mechanic or bit of lore that I’m not familiar with, I will find that information and put it into my prep notes so that I can easily reference it during play. (That might be anything from a specific spell to the rules for grappling to the history of Neverwinter.)

But the absolutely most essential thing you can do when running a published dungeon is prepping an adversary roster. Check out the full article link for a detailed description of adversary rosters and their use, but if there’s literally only thing you do before running a dungeon adventure, it will almost always be this. Adversary rosters make it easy to turn static dungeons into dynamic, exciting environments, and prepping them can be as easy as flipping through the module and listing which monsters are in which rooms. The bang for your buck is huge.

PREPPING PUBLISHED MYSTERIES

When prepping a published mystery, the first thing I’ll do is compile a revelation list:

- What are the essential conclusions that the PCs have to make in order to solve the mystery?

- What locations, people, organizations, and/or events can the PCs investigate to discover clues?

- What clues point to each one of these revelations and where can they be found?

Once you have the revelation list, use the Three Clue Rule to check it for shortcomings: Which revelations don’t have enough clues?

You’ll find that virtually all published mystery scenarios will be filled with these shortcomings, making the scenario unnecessarily fragile in play. This gets into remixing a little bit, but you obviously need to patch up the revelation list: If a revelation doesn’t have at least three clues pointing to it, add more clues until it does.

BACKGROUND/REFERENCE SHEETS

Some published adventures will be polite enough to orient would-be GMs, providing them with clear references for the essential information they need to understand and run the adventure. Many, unfortunately, do not, preferring to present themselves as tantalizing narrative experiences in which the GM must first solve the mystery for themselves!

This can be frustrating, but doesn’t necessarily mean that the adventure isn’t any good.

However, because I don’t want to be put in the position of trying to, for example, solve a mystery at the same as my players to make sure that information I’m presenting is consistent with the solution, I will generally take the time to sort out these sorts of continuity conundrums during my prep and write down an authoritative reference. This can include stuff like a timeline of the Dispatch Murders, the history of the Red Scarab, or the family tree of the Maidenhair family.

There may be other research I do or background lore I create for the adventure. Often this is incorporated into the structure of the adventure itself (that’s where the players will usually be able to learn it, interact with it, and use it), but a central repository collecting all the information for my edification and easy reference is often useful.

For example, when the PCs visit a new city in a campaign set in the 1930’s, I might research what the local newspapers were and include those in my running notes for easy reference and verisimilitude. There are also many fictional settings which have become dense enough that you can actually use very similar research techniques to pull together the deep lore of a location, organization, or person to great effect.

ADVENTURE TEAR-OUTS

In addition to reference sheets, there’s other material in published adventures that can often be reformatted for easier use at the table.

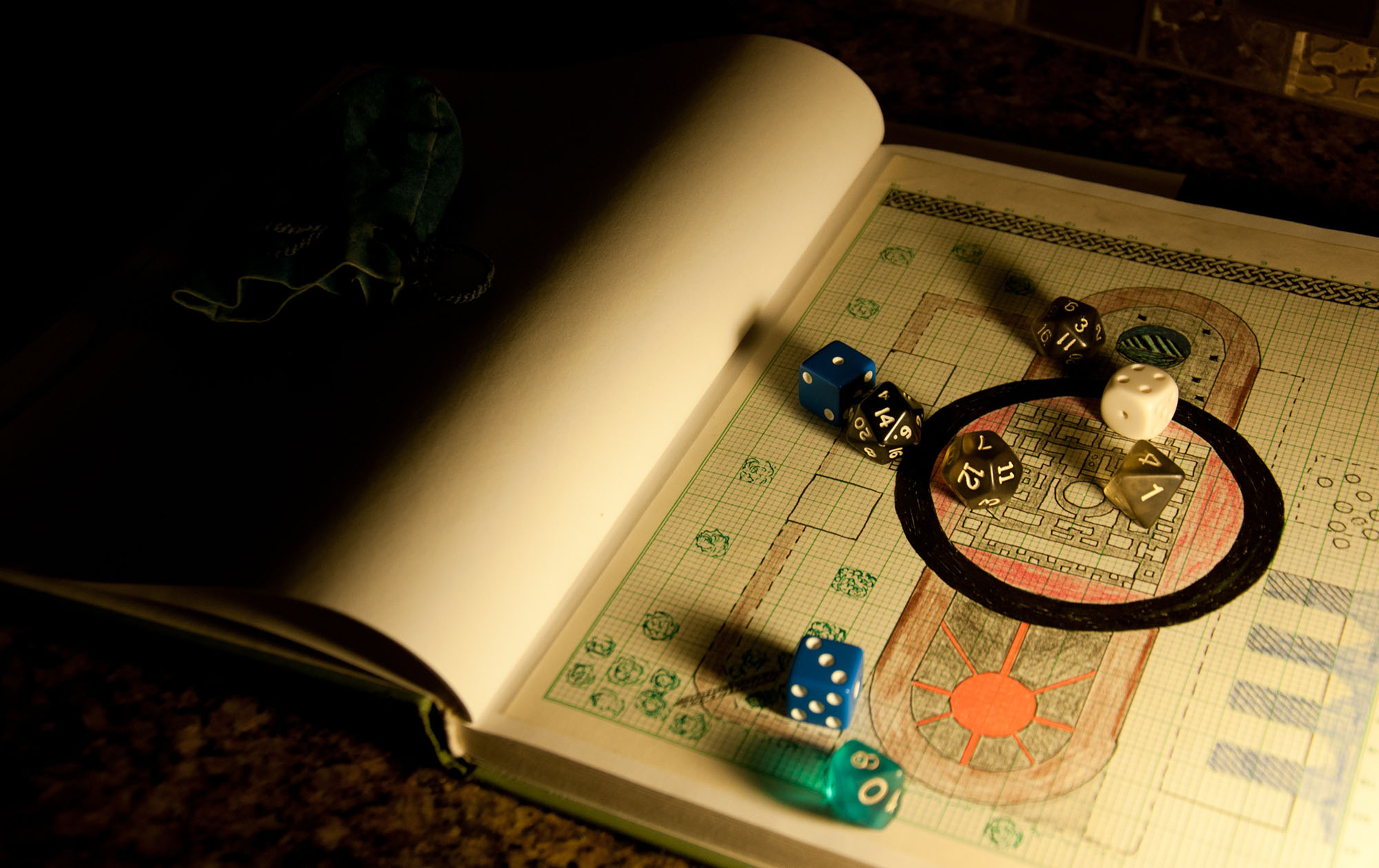

MAPS: If there are any maps in the adventure (particularly for location crawls), I will almost certainly print them on separate sheets of paper. This allows me to separate the map from the rest of the adventure notes and either place it flat on the table in front of me or clip it to my GM screen.

This makes it a lot easier to reference both the map and the adventure key simultaneously. (The quality of life improvement here is astonishing if you’ve never done it before.) I’ve also used counters in combination with maps laid flat on the table to dynamically manage adversary rosters (allowing me to see at a glance where foes are currently located in a complex, and even do things like running security patrols in real time).

STAT BLOCK SHEETS: I will similarly collate stat blocks from the adventure onto reference sheets. (This can include pulling stat blocks from other sources, like the Monster Manual in D&D, which are only referred to by the adventure text.)

In some systems, the stat blocks are short enough that I can often fit every single NPC in the adventure on a single page. In other cases, I’m dividing them according to faction or location or action group (whatever feels most useful for the scenario).

As with the maps, this again reduces page-flipping: When a fight starts, I can quickly grab the appropriate stat sheets, and lay them out. Even if all the stat blocks for a particular fight don’t fit on a single sheet, having them on separate sheets lets me lay them all out at once, so that I can reference stats by just flicking my eyes back and forth. (This may seem like a minor advantage, but once you’ve done it a few times you’ll never want to go back. But I digress.)

As you’re prepping these stat sheets, once again keep in mind the hierarchy of reference: Identify any mechanical elements or abilities in the stat blocks that you’re not familiar with and add them to the stat block. Putting this information at your fingertips during play (instead of, for example, needing to flip through the Spells chapter to figure out how a particular enchantment works) will allow you to simulate system mastery while simultaneously familiarizing yourself with the material through play; in other words, fake it until you make it.

OTHER TEAR-OUT REFERENCES: Maps and stat blocks are the most common examples, in my experience, but there may be other resources in the published adventure that would benefit from being “torn out” of the main text for easy, independent, and/or pervasive reference. I’ve previously mentioned stuff like scenario timelines, NPC templates, and background reference. It might also be stuff like the standard features (door types, ceiling height, etc.) for a dungeon or a random encounter table.

See also Random GM Tip: Swap Notes for Your GM Screen.

PROPS

In Smart Prep, I talk about how props – items that can be physically handed to the players – are almost always a value add when you prep them. This applies to published adventures, too.

The forms these props can take are almost limitless (depending on what the adventure is about), but here are some common forms I look out for.

IMAGES: Published adventures usually include graphical elements. Many of them would be cool for the players to see. Take the effort to pull them, edit them (if necessary), and put them in a format where they can be easily shared (by printing them out, loading them into a virtual tabletop, etc.).

NPC PORTRAITS: These are obviously also images, but as a class receive some special treatment in my experience. First, where possible I’ll also attach copies of these images to NPC roleplaying templates. I find these visual references useful in both quickly finding the appropriate sheet when I’m looking for it and as a touchstone when portraying the character.

Second, if a campaign features lots of paper props, I’ve found it can be useful if NPC portraits are printed out in a distinct format (say, 4” x 6” photos instead of an A4 page). This seems to help players keep their handouts organized so that vital information doesn’t get lost in a Polaroid cascade.

I also think that NPC tent cards (that can either be placed on the table in front of you when an NPC joins a scene or draped over the top of your GM screen) can be incredibly cool. But, truth be told, I never seem to actually find time to do this.

Finally, are there NPCs who don’t have portraits in the adventure? In the era of Google image search, it’s often absurdly easy to find options. (It can actually be so easy that this is also an area where you can fall into the trap of pouring too much energy adding exuberant detail to NPCs with walk-on roles.)

LETTERS & LOREBOOKS: It’s not unusual for scenarios to be designed so that PCs find letters or books which contain clues or other information. These are usually just summarized, but taking that summary and turning it into an actual handout is always going to improve the experience.

For letters, this is fairly straightforward. For books, check out Random GM Tips: Using Lore Books for a technique you can use to achieve the desired effect without writing 40,000 words.

DIORAMAS: We’re straying pretty far into “nice if you have time for it” techniques here, but I do love creating setting dioramas.

The centerpiece of my diorama is frequently a map. When running an urban campaign – whether in modern day Hong Kong, 1930’s New York, or a fictional city like Waterdeep – I love, love, love to have a poster-size city map hung on the wall of my gaming room. World maps are also frequently a great resource, whether for establishing fictional worlds or while running real-world globe-hopping campaigns.

The diorama also includes other pictorial elements that help set the visual motifs of the setting. Stuff like:

- Fashion. What are people wearing? What hairstyles do they have?

- Architecture. What do buildings look like? And not just the big impressive, stuff. What do different neighborhoods look like?

- Activities. What is life like for people in the setting? What are their leisure activities? Where do they shop? If you’re just walking down a street, what do you see?

- Vehicles & Transportation. When the PCs need to get from Point A to Point B, how is that likely to happen?

For more contemporary campaigns, advertisements can be great source for accomplishing or all of these.

A good diorama doesn’t just set mood and help the players visualize exotic settings, it also serves as creative fodder. When the adventure twists in an unexpected direction and you need to start improvising, you’ll have a wall full of buildings, objects, and people that you can point to and say, “That’s what you see.” (I’ll occasionally sneak a few prepped elements of the campaign into a diorama, too, when it’s appropriate.)

You can see several hyper-developed dioramas in the Alexandrian Remix of Eternal Lies.

MINIATURES & BATTLEMAPS

If you’re running a game with miniatures, now is the time to prep the resources you need for that.

Start by running through the stat sheets you prepped for the adventure. Use those (and you adversary rosters) to pull all the miniatures you need. You can also use some of the graphical resources you’ve prepped (NPC portraits, for example) to create custom tokens when appropriate.

Of course, not every creature needs a custom mini. Spot check your likely encounters, though, to make sure you have a sufficient variety of generic tokens to handle the different creature types.

For a battlemap, I tend to use a Chessex mat and just sketch things out during play. But for those occasions where you want something more elaborate, you’ll obviously need to take the time to do that, too – whether they’s pre-drawing maps on modular map components, creating DungeonDraft maps for your virtual tabletop, or prepping your Dwarven Forge collection.

ORGANIZING YOUR NOTES

Roleplaying templates, reference sheets, and adversary rosters – oh my!

How do you avoid getting overwhelmed by all these new tools?

Well, it really boils down to keeping your prep notes organized so that you know exactly where to look for the information that you need. Many of the things we’re prepping are, in fact, aimed to make that easier.

I also find it helps if I generally use the same sequencing of information in my prep notes. My own method has evolved organically over many years, and I don’t think there’s anything particularly magical about it. Most of its utility, for me, is just the fact that I’m familiar with it:

- Reference Sheets

- Revelation List / Adversary Rosters

- Adventure Material (scenes, nodes, dungeon rooms, etc.)

- NPC Roleplaying Templates

- Stat Sheets

- Maps

- Paper Props (I keep a copy in my prep notes for easy reference)

Seek out a system that makes sense to you. Pay particular attention to the first and last things in your notes, as those will generally be the easiest to find quickly during play.

The biggest thing is to make sure that this sequencing is working for you and doesn’t become a straitjacket. If it seems like a particular scenario would benefit from organizing the material in a different way, just do it!

In many ways, this advice applies to every facet of your prep: You’re doing it for you. Prioritize the stuff that makes the adventure easiest for you to run and seems to add the biggest value at the game table. If there’s something that you feel comfortable improvising or which doesn’t seem to significantly enhance the enjoyment of this particular group of players? Skip it!

Focus on the prep that brings the most joy.

FURTHER READING

How to Remix an Adventure

I can definitely agree on props, especially for newbies. I try to have, at the very least, a monster manual handy, if only because my players have no idea what an orc or an ogre looks like. So I can just flip to the appropriate page and tell them, “THIS is attacking.” Having a lot of craft projects at hand helps too – I can make basic booklets and the players spent an absorbed few minutes reassembling a torn journal that contained clues to the plot.

I print pictures off the net, too. My first dungeon was an Anglo-Scottish Border tower and my first street urchin was Maisie Williams as Arya Stark.

Even better are the newish DnD Adventurer’s Guides by Jim Zub. Speaking as a children’s librarian, I find them incredibly attractive, and it’s entirely possible to build a character just by flipping from the race pages, to the role pages, to the armor page, to the weapons page. The only problem is that I just have one or two of each.

As well as using Google image searches for NPC portraits, there are now tools like Artbreeder ( https://www.artbreeder.com/create ) where you can take images and evolve them iteratively or cross them together to create your own portraits. Artbreeder requires you to create an account, but it’s free.

Another simple prep action is handling any “read aloud” sections. Actually read out aloud the read-aloud text — spoken text works differently from text when read. Work out the pacing and cadence, see where you stumble over phrasing, pick up where you can add a dramatic flourish or intonation (i.e. lift it beyond a simple dry and flat reading).

Of course, if you actually hate read-aloud then you’ll want to make them into bullet points to riff off from (at the very least just highlight the key words). Don’t set yourself the challenge (at the game table) of reading through a wall of text and figuring out how to improvise the same information.

I always do a Power Point Presentation for my adventures: there are tons of good artwork in the internet and it allows me to play music specifically to every scene. Also you can organize your slides with hyperlinks, so its easy to jump over stuff that turns out not to be used.

Downsides: it takes a lot of time and it takes some space on the laptop (100MB+ for 10-15 Slides). And if you have too many slides (I arrived at roughly 300 location slides for waterdeep + quest-specific slides) you can get confused where the hell you have to click to get to the burning lute tavern^^ (was it the raven on the lanternpost or the house in the background…)

However, even though I manage to click on the wrong item at least twice every session, I’ve received only positive feedback from my players so far (some even said it was the best thing about my DMing, which could also mean that I’m a bad DM^^

It’s actually a lot like what you describe as your dioramas, but more interactive (and more time-intensive to prepare I guess). I also often add pictures of player characters, npcs, monsters etc (and if I’m having too much time, animations) to the slides.

One thing that I got for prepping battle mats ahead of time was a large 1in grid easel pad. Its 27 x 34 inches and was 50 sheets for about $20 at my local art store.

Amazon has some as well. Here is a link if anyone is interested:

https://www.walmart.com/ip/Easel-Pad-1-Grid-Ruled-27-x-34-White/21401705