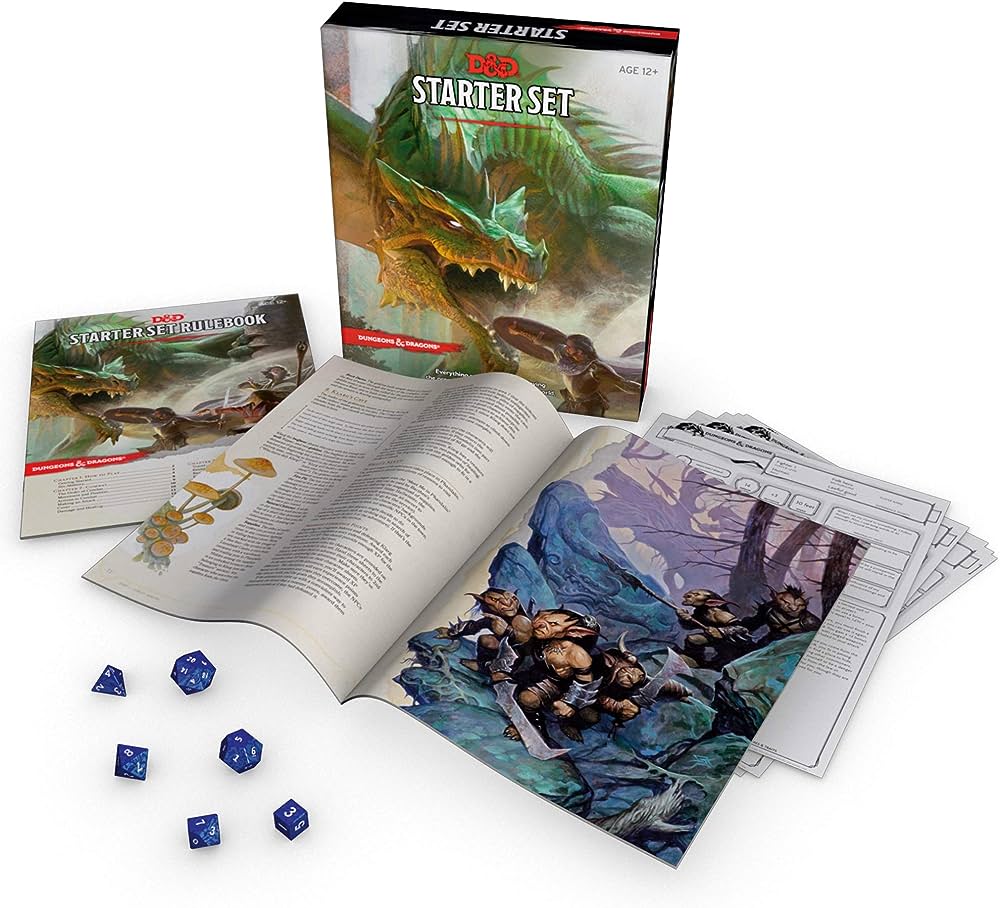

The original 5th Edition D&D Starter Set was released in 2014, reaching shelves shortly before the core rulebooks.

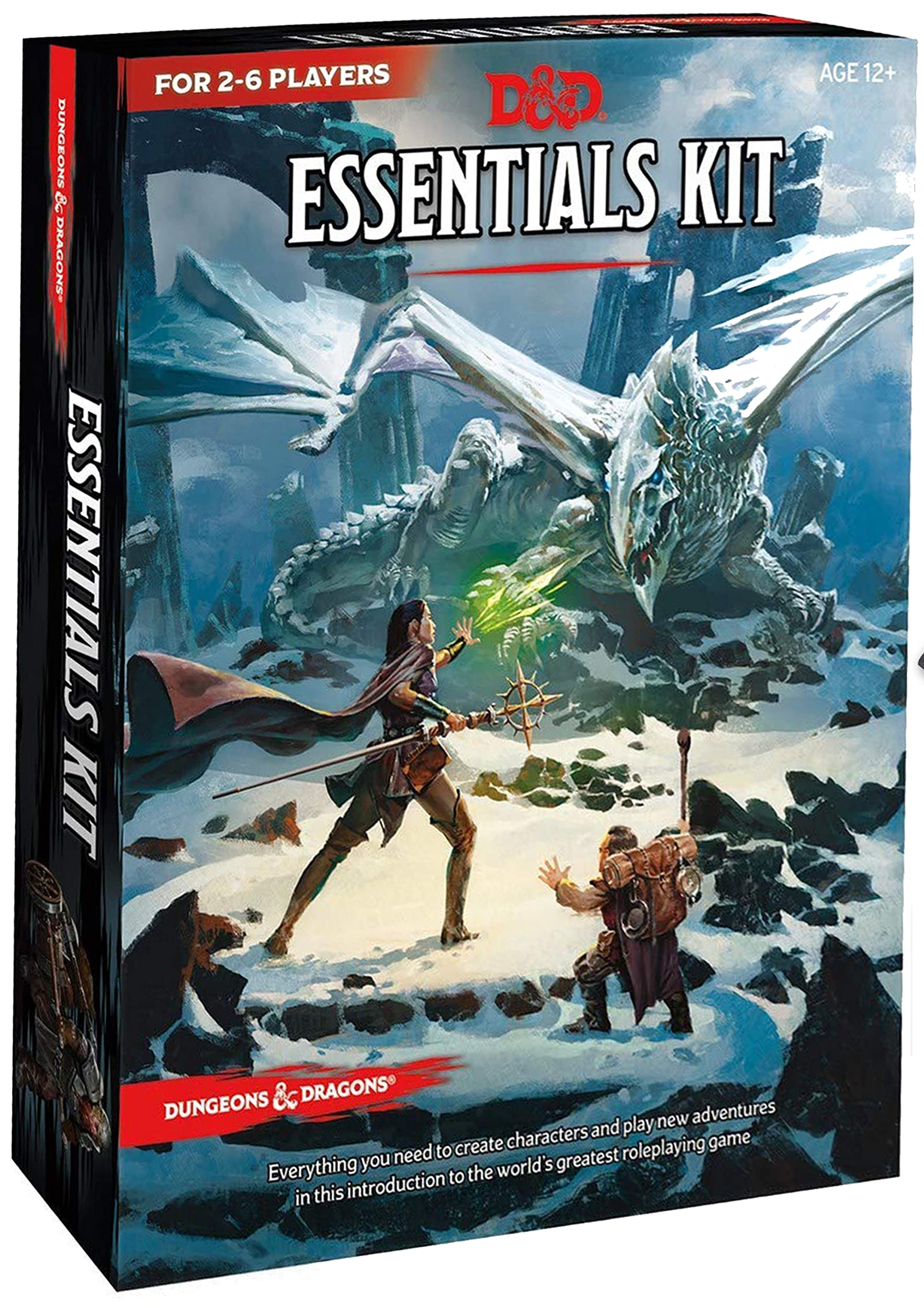

In 2019, Wizards of the Coast released a new introductory boxed set: The D&D Essentials Kit.

Your first thought might be that they were replacing the Starter Set with a new and improved game box, but this wasn’t the case: The Starter Set remained in print and on shelves next to the Essentials Kit until early 2022, when it was replaced by the new D&D Starter Set: Dragons of Stormwreck Isle.

(Along the way, Wizards also published additional starter sets featuring Stranger Things and Rick & Morty.)

So why do we have so many introductory boxed sets?

I suspect it has less to do with what’s inside the box and more to do with the box existing in the first place.

In the mass market and big box stores, entertainment products have a shelf life: If you’re successful enough to crack that market in the first place, your game will be stocked, it will sell, and then at some point the big box stores will stop stocking the game and the sales will stop. If you’re lucky, this will be based on your sales (because if you can keep selling, then you can keep selling), but more often it’s just a matter of time: Automated reorder systems will play it safe by ordering fewer copies each time; which results in fewer sales; which results in a smaller reorder or, eventually, no reorder at all.

By having multiple introductory boxed sets for sale, Wizards of the Coast pays a cost in customer confusion: Someone wanting to play D&D for the first time may become uncertain which of these nigh-identical products they should buy.

But what they gain is a new SKU; a new product code. Each time they release a new SKU, it’s a fresh opportunity for their marketing team to go back to the big box stores that have dropped the previous boxed set and get D&D back on the shelf in Target or Walmart or Barnes & Noble.

If you’re reading this review, though, you’re probably not an account manager at Walmart. (If you are, there’s a book you should definitely acquire.) You’re a gamer. Or maybe a search engine brought you here because you’re interested in becoming a D&D player.

So if you’re looking for your own introduction to D&D, is the Essentials Kit what you should pick up? Is it worth grabbing a copy if you already own the D&D Starter Set? What if you already own the core rulebooks?

This review will probably make more sense if you’re familiar with my review of the D&D Starter Set, so you might want to read that if you haven’t already. But here’s a quick overview of what I’m looking for in an introductory boxed set like the Essentials Kit:

- A meaty, full-featured version of D&D.

- An introduction for complete neophytes to roleplaying games that would not only teach them how to play, but how to be a Dungeon Master.

- A complete gaming experience, even if you never picked up the Player’s Handbook or Dungeon Master’s Guide.

OPENING THE BOX

So let’s take a peek inside the D&D Essentials Kit.

Where the D&D Starter Set was fairly barebones, the Essentials Kit packs in a bunch of gimmicks and gewgaws to fill the box:

- The 64-page Essentials Kit Rulebook, doubling the size of the 32-page rulebook from the D&D Starter Set. (Notably absent, however, is the index that the D&D Starter Set included.)

- The 64-page Dragon of Icespire Peak, which serves as an adventure book and monster manual.

- Six blank character sheets.

- A full set of dice.

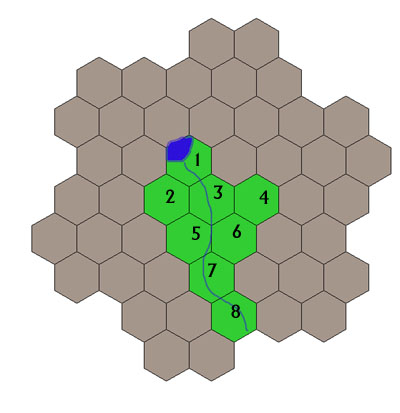

- A two-sided poster map of Phandlin and a hexmap of the surrounding area.

- A mini-DM screen.

- 108 cards on perforated sheets, including initiative cards, quest cards, an oddly arbitrary selection of NPCs, magic items, and conditions.

- A cardboard tuck box for your cards.

Notably, both the rulebook and the adventure book have been given cardstock covers, replacing the flimsy pamphlets from the D&D Starter Set with books that can actually endure some meaningful use at the table. This was a shortcoming I called out in my review of the Starter Set, and it’s great to see it improved here. Along similar lines, the dice set in the Essentials Kit is larger, including the second d20 (for advantage/disadvantage rolls) and 4d6 whose absence I’d noted.

I’d also mentioned that a poster map of the region around Phandalin would have been a great addition to the D&D Starter Set… and here it is! Including a mini-DM screen is also an inspired choice, not only giving the game a little more “table presence” when you get set up for play, but also giving the new DM a valuable cheat sheet that will help them master the game.

I’m a little more agnostic leaning towards pessimistic when it comes to the cards. There’s a mishmash of stuff here:

- Condition cards.

- Initiative count cards.

- Sidekick cards.

- Quest cards.

- Magic items.

I find the basic utility for quite a few of these cards fairly suspect, and while I respect the quixotic quest to include “value-add” components to introductory boxed sets down through the ages, I think it mostly sets up a false expectation of what you “need” to run a D&D adventure.

(You do not, in fact, need to prep quest cards or NPC cards.)

Your mileage may vary.

RULEBOOK v. RULEBOOK

Before opening the Essentials Kit box, I was actually expecting to find the exact same rulebook that Wizards of the Coast had used in the D&D Starter Set. The rules of the game, after all, hadn’t changed.

Instead, the Essentials Kit Rulebook has doubled in size, from 32 pages to 64 pages!

There are several reasons for this, but the biggest one is that the Essentials Kit Rulebook includes character creation! Which was another thing I thought was missing from the D&D Starter Kit! This is fabulous!

But there are a couple things that could have made it even better. First, the ideal introductory boxed set would include both character creation rules and pregen characters. Character creation gives you a fully functional game, while pregens let new players leap directly into the action.

Second, if you’re going to have a bunch of these introductory boxed sets in print at the same time, I’d love to see them go a little wild with the class/race selections. If the D&D Starter Set features human/dwarf/elf and fighter/cleric/rogue/wizard, I’d have loved to see the Essentials Kit feature something like dragonborn/gnome/half-orc/tiefling and druid/monk/ranger/warlock. Mix it up! Instead, the selection here is pretty tame (although they do toss bards into the mix).

Another major addition here are rules for Sidekicks. This is a very smart addition, because it lets a DM easily run the game for a single player (playing a PC plus sidekick). That’s huge for an introductory boxed set, because it makes it a lot easier for a new player looking to play D&D for the first time to start playing.

It’s interesting looking through the two rulebooks side by side and seeing how the sequencing of information shifts subtly from one to the other, but for the most part everything seems to be pretty equivalent. (With the exception of experience points, which have been removed from the Essentials Kit.)

There are a couple other bits of rules-type content that don’t technically appear in the Essentials Kit Rulebook, but which I want to comment on here: Monsters appear as an appendix in the adventure book and magic items have been moved onto the item cards.

The monsters are given better descriptions in the Essentials Kit than in the Starter Set, but I found the selection of both monsters and magic items disappointing. There’s not really a way for me to objectively demonstrate this, but looking at the Starter Set I felt like I could take the included magic items and monsters and remix them to create a bunch of different adventures. But with the Essentials Kit, I just… don’t. It feels like there’s a lack of variety, or that key niches have been left unaddressed.

So the inclusion of character creation is a major upgrade for me, but overall I think, from a mechanics standpoint, that the Essentials Kit is something of a mixed bag for me. But I think it has a slight edge over the Starter Set here.

DRAGON OF ICESPIRE PEAK

The Essentials Kit includes an all-new adventure book: Dragon of Icespire Peak.

Like the Lost Mine of Phandelver from the D&D Starter Set, however, Dragon of Icespire Peak is set in the village of Phandalin.

In fact, at first glance, Dragons of Icespire Peak is structurally very similar to Lost Mine of Phandelver: You’ve got a bunch of individual adventures, forming a complete Tier 1 campaign. You don’t need to complete these adventures in any particular order, with the PCs being able to gather adventure hooks in the hub of Phandalin and then choose which ones they want to pursue. The whole thing ultimately culminates in a cap adventure where the PCs hunt down the titular dragon that’s plaguing the region.

So this should be just as good as Lost Mine of Phandelver, right?

… right?

I’m not going to beat around the bush here: It’s not.

Dragon of Icespire Speak gets off on the wrong foot, in my opinion, from the very beginning by giving some absolutely terrible advice to the first-time DM: Instead of reading the adventure book ahead of time, the DM is instructed to wait until the players are creating their characters and then “read ahead” to figure out how the adventure works.

(This is despite the fact that, on the same page, the DM is told that part of their role is to help the players create their characters. So… yeah. Do that and also read the adventure for the first time. At the same time.)

I think what they’re trying to do is support people who want to open the box and immediately play the game: They’d obviously have to claw out some time during the session to read the adventure, right? Realistically speaking, however, this is never going to happen: There’s a 64-page rulebook that needs to be digested before play can begin. So all you’re left with is some terrible guidance that will lead new DMs straight into an almost certainly horrific first-time experience at the gaming table.

This is particularly true because Dragon of Icespire Peak isn’t designed with a single initial scenario. Instead, the campaign begins with the PCs standing in front of a jobs board posted outside the townmaster’s hall, where they’ll immediately be able to choose between three different adventures. (Read fast, Dungeon Master!)

This jobs board is, in fact, the primary structural problem I have with Dragon of Icespire Peak. Unlike Lost Mine of Phandelver, in which the adventures were all connected to each other and emerged organically from interactions with the game world, Dragon of Icespire Peak primarily delivers Quests by having the DM hand the players a Quest Card when they read the Quest on Harbin Wester’s job board.

The result is an experience which has been video-gamified.

To be clear here, I don’t have an inherent problem with using a jobs board in D&D. The problem here is the implementation.

To start with, for many of the Quests there’s no clear mechanism by which Harbin Wester could have become aware of them. In other cases, the continuity doesn’t make sense. For example, there’s one quest where the PCs are sent to check on a ranch that was attacked by orcs:

- Orcs attacked the ranch. Almost everyone there was killed.

- “Big Al” Kalazorn, the ranch owner, was captured.

- A ranch hand escaped and rode to Phandalin.

- Harbin Wester then waited ten days before sending the PCs to see if Kalazorn is still alive.

In addition to frequently not making any sense, these quests are all disconnected from the world around them. In fact, the adventure frequently seems to go out of its way to eschew these connections!

For example, there’s a wilderness encounter in which the PCs stumble across an unattended riding horse branded with BAK (for “Big Al” Kalazorn). That’s good! That’s a clue that something is wrong at Big Al’s ranch and the PCs could follow that lead and discover the adventure in a way that makes the world feel like a real place!

… except that encounter is hardcoded so that it ONLY occurs if the PCs are already on their way to the Big Al’s ranch.

This lack of continuity, context, and connection, combined with the fact they’re delivered in the most impersonal manner possible (Harbin literally hides inside his house and won’t let them in), makes all of the Quests feel like meaningless errands, something which I feel is only further emphasized by the adventure using quest-based leveling. These are not things that the players will actually care about; they are rote obligations.

A subtler difference is that Dragon of Icespire Peak’s Quests are filled with a lot of Thou Must imprecations as opposed to Lost Mine of Phandelver’s presentation of options and tacit support for open-ended play driven by the players.

On a similar note, a lot of the goals in Dragon of Icespire Peak default back to “clear the dungeon.” This, too, greatly reduces the players’ ability to creatively engage the campaign and forge their own destiny… which once again gives the sensation of trudging through obligations.

I also have a much longer list of specific concerns when it comes to the individual adventures in Dragon of Icespire Peak. Stuff like:

- There’s a 60-foot-long tunnel. If the PCs don’t declare that they’re searching for traps, the tunnel collapses when they reach the half-way point and everyone in the tunnel (which, given the length of the tunnel, is likely to be all of the PCs) is automatically buried. If you’re buried, you cannot take any actions and the only way to escape is if someone who isn’t buried helps you get out. So… yeah. That’s just an instant death trap. (And there are a bunch of other death-trap issues in this vein, like the adventure that dumps 1st-level PCs run by neophyte players into multiple fights with ochre jellies.)

- There’s an adventure where a gnomish king has been driven insane by the knowledge that a mimic is eating his subjects. Okay… sure. But as soon as the PCs kill the mimic, the king’s insanity is instantly cured! … that is not how madness works. (Fundamental breakdowns in worldbuilding, character, and basic logic are far too frequent here.)

- That same adventure, however, has a lot of really neat ideas and interesting roleplaying opportunities. It’s fairly complicated and relatively difficult for a DM to run. Which would be okay… unless you position it so that it can be the very first adventure a brand new DM using the Essentials Kit would need to run. Which is, of course, exactly what the adventure book does. Why not scale this adventure up a couple levels so that it can come in the middle of the campaign after the DM has a bit more experience under their belt? (There’s a number of strange sequencing decisions like this.)

Dragon of Icespire Peak is, ultimately, a mediocre but passable campaign. In comparison to many other introductory adventures, it’s actually quite good. But when directly compared to Lost Mine of Phandelver — and, of course, one is more or less compelled to make that comparison — it does not fare well.

THE VERDICT

In the showdown between the D&D Starter Set and the D&D Essentials Kit, which one comes out on top?

With the D&D Starter Set out of print, of course, this is something of a moot point. The Essentials Kit wins more or less by default.

Even when both were available, however, it’s hard to pick a clear winner. I’d probably give the edge to the D&D Starter Set strictly on the strength of Lost Mine of Phandelver: In large part, an RPG lives or dies by its adventures, and Lost Mine of Phandelver is just a fundamentally better campaign.

The truth, though, is that if you were to merge these two sets together, you’d likely end up with a near-perfect starter set in the fusion: Give me the rulebook from the Essentials Kit. Give me the campaign from the Starter Set.

More than that, though, when we start talking about combining the Essentials Kit with the Starter Set, we suddenly discover that Dragon of Icespire Peak suddenly becomes vastly better simply by running it at the same time you’re running Lost Mine of Phandelver. (Which is, of course, quite trivial to do.)

Having the impersonal, decontextualized jobs board as the central pillar of your campaign is alienating and results in a shallow, forgettable, and even frustrating experience for the players. But if you take that same structure and add it as a spice to a larger campaign, suddenly it comes to life! The roots of Lost Mine of Phandelver will dig in, twining themselves around the adventures of Dragon of Icespire Peak, lending them the context and depth that they natively lack.

(I suspect this also means that the D&D Essentials Kit is a perfect companion to the Phandelver and Below: The Shattered Obelisk campaign, which remixes the material from Lost Mine of Phandelver, although I haven’t read that book yet.)

Of course, in actual practice, I’d still recommend that you’d be best served by make a number of small tweaks and modifications to contextualize, connect, and make relevant these adventures. (You could use Lost Mine of Phandelver as a model of how to do that, or check out articles like Using Revelation Lists.)

In the final analysis, the D&D Essentials Kit is a pretty solid introductory boxed set. I wish it was a little better, but I wouldn’t really hesitate giving it as a gift to someone discovering D&D for the first time. And at just $25, it’s not hard to justify grabbing a copy to supplement your Lost Mine of Phandelver, Phandelver and Below, or almost any Tier 1 campaign based out of a typical fantasy village.

Grade: B-

Rulebook Designer: Jeremy Crawford

Adventure Designer: Christopher Perkins

Additional Adventure Design: Richard Baker

Adventure Development: Ben Petrisor

Publisher: Wizards of the Coast

Cost: $24.95

Page Count: 128

FURTHER READING

Review: D&D Starter Set (2014)

Review: Dragons of Storm Wreck Isle (2022 Starter Set)