IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 33A: DOWN THE SEWER HOLE

December 28th, 2008

The 18th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

With the two cultists securely manacled, they went upstairs to deal with the tentacular horror of translucent protoplasm.

Tor and Agnarr removed the barricade of furniture from in front of the door. Then Tor kicked open the door and stepped through.

Its abode disturbed, the creature surged out of the broken cocoon and lurched its way across the room. As it came, it spat a viscous glob of acid spittle towards Tor’s face. Tor narrowly dodged the spittle and then sinuously whipped back the other way as a pseudopod lashed out towards him.

Having kept his balance despite his acrobatic dodging, Tor lunged forward with his own blade. But the creature burst apart – opening a gap through which Tor’s sword passed harmlessly.

As the creature reformed its mass, however, Agnarr slipped into the room as well, and cut down at it. The barbarian’s blade ripped into it, leaving an acrid stench as it burned its way into the heart of the creature.

This sent the creature into a frenzied rage. It spat venom randomly in all directions, catching Dominic in the eyes, and then lashed out at Agnarr with a half dozen tentacles. Agnarr managed to weave his way past a few of them, but the sheer mass of the attack overwhelmed him – four of the pseudopods struck him and latched on. These clung to his flesh and then, using them like anchors, the creature hauled itself towards him. Before anyone could react, the creature had engulfed him.

Tee tumbled into the room and stabbed at it, hoping to lure it off of Agnarr. It spat venom in response. She was struck in the face and cried out in pain, trying to wipe the blinding, burning goo out of her eyes.

Ranthir, seeing Agnarr’s plight, hurled the familiar spell of enlargement at him. At its touch, Agnarr literally grew his way out of the engulfing creature. It ripped painfully free from his body, leaving trails of blood to pour down onto the floor.

The creature retreated from the now enormous Agnarr, spitting venom into his eyes as it went. Crying out from the literally blinding pain, Agnarr swung his greatsword—

–and struck Tee! The blow cut her down where she stood.

But the wide swing also had the effect of forcing the creature back into the corner of the room, from which – with no place to flee – it propelled itself forward again, latching two of its large pseudopods onto Agnarr’s chest. As the others stared in horror, it began sucking the blood from Agnarr’s body – sending misty trails of crimson fluid pulsing through its amoeba-like body.

The barbarian, still fighting blind, raised his sword back and struck mightily at the floor directly beneath the creature. The unsupported floorboards splintered beneath the strength of the blow, and the creature fell through the hole. It tried to drag Agnarr down after it, but Agnarr’s prodigious strength held and the tentacles ripped free.

Dominic, still blind, cried out in fright: “I think the floor is collapsing! We need to get out of here now!”

Agnarr’s vision, however, was clearing now, and he could see the creature still writhing on the lower level. With a grunt he leapt up and plunged down through the hole, driving all of his enlarged weight (more than two tons) onto the creature.

With a squalmous squelch, the creature burst – spattering eddies of protoplasmic grotesquerie through the room.

Agnarr straightened up, poking his head back up onto the second floor. He saw Tee lying in a pool of her own blood. “What happened to Tee?”

His wounds were still bleeding badly, but Elestra was able to tend to that.

Dominic was regaining his own vision. “Ah!” he cried. “You weren’t that big the last time I saw you… What happened to Tee?”

Dominic was able to heal Tee’s wounds easily enough. With a grimace of pain she sat up.

“What happened to me?”

DOWN THE SEWER HOLE

They were satisfied that they had done everything they could to cleanse the apartment complex of the horrific experiments that had been conducted there (albeit while wreaking massive property damage).

“Well, at least we didn’t burn the place down.”

“We did not burn down that house!” Tee insisted.

“What should we do now?” Tor asked.

“We should hurry,” Tee said. “It’s been at least ten minutes since the fight broke out on the street.”

“Right,” Elestra said. “The guard will be coming.”

“Or more cultists,” Tee said.

“Yes. That would be worse,” Dominic said.

They collected their two cultist prisoners (replacing the manacles with knotted ropes firmly tied by Tor) and dragged them over to the hole in the back corner of the first floor. Climbing down the rope ladder they found themselves, as they had predicted, in the sewers. Tee came last, dragging a rug over the hole behind her to help conceal its presence, cutting the rope ladder, and then floating down using her boots of levitation.

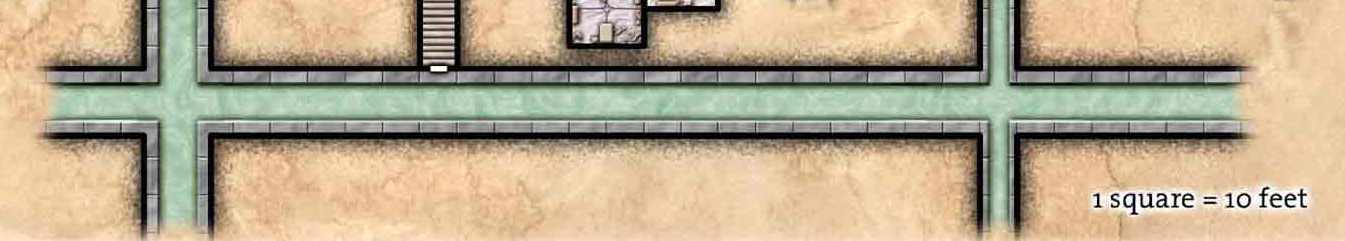

They were standing at the intersection of four major sewer passages. Narrow walkways of beslimed stone ran along a wide, slowly flowing channel of raw sewage. Agnarr examined the ground and determined that the walkways to the north and west had recently seen a great deal of traffic. They suspected that was the direction the cultists would come from, so they decided to take the prisoners a little way down the southern passage instead.

Quickly searching them, they found several carefully folded and oiled silk, each of which contained some sort of alchemical substance (which Tee guessed was poison). They also turned up a thick sheath of research notes in a hidden pocket of the spellcaster’s robes. They took the time to study these and the other papers that they had recovered from the alchemical laboratory upstairs.

THE BOOK OF VENOM’S TRUTH

This small, gray-covered volume is a paean to all manners of vile activities – drug abuse, sexual perversions, acts of cruelty and violence – treated with the reverence of holy ritual.

In totality, the book appears to be a cult manual for the “Brotherhood of Venom”. They worship chaos, speaking of the “slow swarm of the Elder Brood” – by which they appear to mean the slow, methodical, and (above all) secret sowing of chaos and dissolution. They perceive ordered society as a curse and seek to undermine it through a slow and steady erosion of disintegration.

Entire passages are given over to describing the basic dynamics of power and how to subvert them – serving as a generic manual n how to infiltrate the highest levels of a society through its most important individuals.

The cult prefers the clandestine. They are patient and careful, never wanting the authorities or other potential opponents to know they exist.

A name is scrawled on the inside back cover: BROTHERHOOD OF PTOLUS

THE MASKS OF DEATH

This folder of blood-red leather contains a collection of associated parchments which appear to serve as something of a cult manual for a group calling itself the “Brotherhood of the Deathmantle”, the Death’s Grimace, or the Tears of Blood.

The cult serves chaos through the worship of murder and slaughter. The more chaos and fear each murder creates, the greater the veneration. Mass murder – the slaying of a whole town, a whole city, or a whole nation – is their ultimate goal.

Each cultist wears a death’s head mask, usually of copper or bronze but occasionally of iron painted skull-white. The cult frequently associates with the undead, and there is even the suggestion that the most faithful among them are undead themselves. They venerate graveyards as holy places and speak of the end of days as “the grave of all worlds”.

Much of the book is given over to the painstaking detailing of the instruments of death: The making of poisons, the care of weapons, and so forth.

Some of the manual is given over to what they would consider the ultimate religious ecstasy: The death of a god.

ALCHEMICAL NOTES ON ASKARA

These notes detail the creation of a magical poison referred to as askara. The notes appear to have been frequently altered, apparently in an effort to perfect the process. The effects of the poison are not described.

The notes appear to combine alchemical and mystical knowledge credited to both the Ebon Hand cultists and the Brothers of Venom.

OBSERVATIONAL NOTES

ON VENOM-SHAPED THRALLS

These are detailed notes on the effects of a poison referred to as askara. The poison is designed to mutate its victim in a prolonged misery that lasts for weeks or even months before the victim dies. During this time, however, the victim’s mind becomes pliable – effectively becoming a slave of those administering the poison.

When victims are injected with askara, they weaken until they collapse. Within twelve hours, their bodies secrete a dark, syrupy substance that covers them and then hardens, forming a black, spherical cocoon. Within another twenty-four hours, the victim emerges from the cocoon, mutated into a hideous amalgam of an insect-like creature and their former selves.

A large section of these notes detail the perfection of a solution that must be applied to the cocoons during the gestation period. Without that solution, the resulting creature “lacks cohesive physical form”. This solution appears to have been difficult to perfect, and was reached only after “Wuntad assured us access to the teachings of the Deathmantles”.

Other notes refer to “unexpected activity in the post-emergent cocoons” including a reference to “violet slime” and “secondary spontaneous cellular generation”, but these are not particularly detailed.

Running the Campaign: Fantasy Sewers – Campaign Journal: Session 33B

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index