DISCUSSING

In the Shadow of the Spire – Session 33A: Down the Sewer Hole

They collected their two cultist prisoners (replacing the manacles with knotted ropes firmly tied by Tor) and dragged them over to the hole in the back corner of the first floor. Climbing down the rope ladder they found themselves, as they had predicted, in the sewers. Tee came last, dragging a rug over the hole behind her to help conceal its presence, cutting the rope ladder, and then floating down using her boots of levitation.

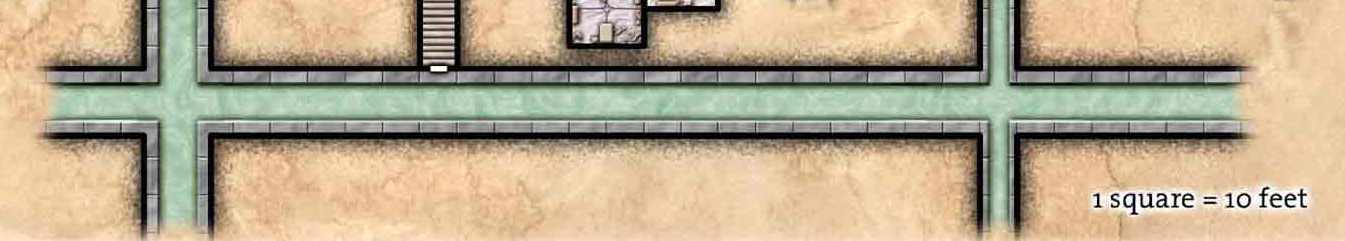

They were standing at the intersection of four major sewer passages. Narrow walkways of beslimed stone ran along a wide, slowly flowing channel of raw sewage. Agnarr examined the ground and determined that the walkways to the north and west had recently seen a great deal of traffic. They suspected that was the direction the cultists would come…

You’ll often read that the large, walkable sewer tunnels that we see in movies, TV shows, and our D&D campaigns are complete nonsense and have no basis in reality.

But this is not entirely accurate.

It’s true that sewer systems (both today and historically) were mostly made up of pipes too small for humans to traverse. (The drain in your sink does not drop directly into a tunnel.) It’s also true that medieval European cities mostly lacked sewer systems of any kind. (Paris, for example, didn’t have an underground sewer until 1730.)

But that doesn’t mean sewer systems don’t have any walkable tunnels. (They do. Ironically, Paris now has one of the largest networks of walkable sewer tunnels.) It’s also not true that sewers are a modern invention, or that historical sewer systems lacked the larger tunnels. (As far as I can tell, they were actually more common because (a) it was more likely that humans would need access to clear out clogs and debris and (b) older sewer systems were more likely to be primarily focused on draining storm and flood water than waste disposal, and therefore needed very high capacity.)

Rome, for example, had the Cloaca Maxima, which had tunnels, walkways, the whole bit. The final act of The Third Man, Carol Reed’s classic noir film featuring Orson Welles, takes place in the sewers beneath Vienna and was filmed on location: These spacious tunnels were also constructed by the Romans in the 2nd century. Other Roman sewers of similar design have been preserved in Herculaneum and Pompeii.

Although it appears that Romans were allowed to connect their privies to theses systems, recent archaeology suggests that they rarely did: Their toilets notably lacked traps, so nothing would stop sewer gases (and smells) from simply coming up the toilet. Animals and other pests would also use them to invade homes. (We have tales about alligators coming up from the sewers: Aelian and Pliny tell us of an octopus in Iberia that would swim up the drainage tunnels at high tide and sneak into kitchens to eat the pickled fish. On a similar note, there were Victorian tales of pigs living in the sewers of Hampstead. But I digress.)

On the gripping hand, it would nevertheless be quite unusual to find a sewer system like this–

–with twenty-foot-wide passages kept surprisingly tidy and flanked on both sides by walkways. (The entrances to weird, subterranean caverns are actually slightly more plausible: It wasn’t unusual for ancient sewer construction to piggyback or unexpectedly run into preexisting underground structures. In fact, many ancient sewers, including possibly the earliest version of the Cloaca Maxima, were just rivers that had been bricked over.)

But all of this, of course, begins to rub up against the fantastical architecture at the heart of D&D. If the cities of D&D were meant to be strictly modeled on the cities of medieval Europe, we could sagely nod our heads, stroke out chins, and pronounce that it’s just silly for them to have sewers like this.

But D&D cities aren’t medieval European cities, are they?

First, there’s no reason that a completely alternative history wouldn’t see your D&D civilizations preserve the hydrological knowledge of the Romans.

Second, as we’ve seen, some medieval cities DID have sewers like this because they preserved Roman ones. (And it’s not like D&D-land isn’t peppered with ancient civilizations.)

Third, even our declaration of “medieval European city” is pretty biased. The Byzantines were still building large waterworks during this time, as did the Ottomans after the fall of Constantinople.

Fourth, the construction capacity and resources of a typical D&D setting far outstretch those of medieval Europe due to the presence of ubiquitous magic (whether arcane or divine).

So if I want to feature something like this in a D&D campaign, instead of reaching for reasons why it can’t exist, I instead reach for the reasons that it can and then apply them.

In doing so, of course, I don’t necessarily need to achieve absolute realism — just plausibility. Because, sewers aside, fantastical construction is a concept that D&D’s worldbuilding inherently holds in tension. The entire game is fundamentally based on architecture which is simultaneously fantastical and irrational: To what possible purpose could the tunnels beneath Castle Blackmoor have been constructed?

(There’s a reason that both Gygax’s Greyhawk and Greenwood’s Undermountain are justified by the whims of a Mad Mage, Zagyg and Halaster respectively.)

We don’t want to abandon logic entirely — because then the PCs are simply trapped in a madhouse of random noise, unable to meaningfully apply thought or problem solving — but the skein of verisimilitude can be pulled very tight when it comes to D&D and a milieu which often operates only on laws of convention.

Campaign Journal: Session 33B – Running the Campaign: Bond. The Opposite of Bond.

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index

You can justify the idiosyncrasies of Fantasy Sewers by other aspects of the settings that house them.

For example: Otyughs. Whether those ancient civilizations bio-engineered them to eat trash or not, they can trudge through these places, doing their necessary work. You wouldn’t want them to get bored enough to start walking around topside, especially not in anyone rich might be holding an event.

But a feast for the rich would be exactly what an otyugh would be interested in. Just think of all that tasty high-value sludge pouring into the sewers under the vomitoreum. It turns out bees require a specific size of opening to make a hive, and one built with the wrong size could be palatial inside, but the bees don’t care. Maybe the otyughs require sewers to be built to their specifications in order for them to serve as cleaning crew?

Another consideration, on the topic of sewers being built to house garbage feeders like Otyugh or Slimes, is that guards or sellswords would need to be able to get into the sewers to cull them if they became too aggressive. Having too much food would mean they would breed out of control and eventually need to push towards the surface, which would mean steady work for any travelers good with a blade. And to save on human death (not that they care about your life, it’s just cheaper), that also means that the sewers need to be easy for a humanoid to get into and out of, possibly quickly and possibly while extremely sick, but hard for a Large aberration.

There’s also the possibility that the sewers weren’t made by men. There are giant burrowing creatures in many settings, after all, maybe they either connected their sewers to an existing tunnel (perhaps with reckless disregard for if the creature was still alive… and hungry) or used magic of some kind to have one carve the sewers to their specifications. A city built on top of what they thought was a dead hive of giant insects, only to find out that pouring their waste into the empty tunnels woke up the queen from her millenia of hibernation, sounds like a great plot, or even campaign, hook.

Or possibly we have it backwards. Instead of the sewers being dug under the city, perhaps the dwarves were digging their way up and, having reached the surface, turned the old tunnels into a wastewater project generations back. They’re… mostly abandoned.

I went to the Paris sewer museum, which is actually in (disused, I hope!) sewers. The bigger Paris sewers actually do have this wide-passages-with-walkways layout (though probably narrower than 20′), but the water channel in the middle is far deeper than I realised. From D&D maps always assumed it was maybe 3 feet down to the central channel, but it’s more like 6 or 10 feet just to the water surface (at least when it’s not raining).

They also have these giant iron spheres used to clean the sewers, which I definitely plan to include next time I do a sewer dungeon

The real world also has cities that are “tels” like Jerusalem: where the modern city is built on top of the buried ancient city, sometimes in multiple layers. So the tunnels beneath the city are actually just the streetways or houses of the former city which haven’t been filled with sediment. This is also probably the easiest way to make a Jacquayed underground space: just imagine a city block where many of the alleys and buildings are inaccessible, so the random openings that are traversable create loops and alternate routes.

As RatherDashing said, many modern cities have an “underground” of buildings that were paved over to create sewer systems in the mid-1800’s. I’ve heard of several cities abandoning their original street level, raising the sidewalks up to the second story of buildings, and using the new “basement level” as stormwater runoff. The one I’m personally familiar with is the “Seattle underground tour,” which wasn’t all that impressive in person, but interesting from an ideas and worldbuilding perspective. There were photos of people using ladders to get up to the wooden sidewalks!

This blog post on running a fantasy campaign set in the sewers of Ptolus was an absolute gem! I thoroughly enjoyed reading about the intricacies of creating a compelling underground environment for players to explore. The way you described the various challenges, encounters, and atmosphere of the sewers was incredibly vivid and immersive. I especially appreciated the emphasis on incorporating diverse elements like secret passages, unique creatures, and environmental hazards to keep the players engaged and on their toes. Your tips and suggestions for handling sewer-themed campaigns were insightful and practical. Thank you for sharing your expertise and providing such valuable resources for fellow roleplaying game enthusiasts. Can’t wait to delve into more of your gaming content in the future!

A couple notes. One, Rome *has* the Cloaca Maxima. It still drains that area just like it always has, and I visited the exit to it last year. (There was a couple homeless dudes who’d set up tents there, so it’s not actually a very nice place. But my wife and I are both big nerds, big fans of classical history, and she’s an engineer. So it was worth walking a bit out of our way.)

Two, I was designing a big storm sewer system for a game I ran a while back, and one of the terrain features/traps I made for it might be of interest here.

**Sewer Valve**

The great and ancient sewer to drain the marshy lands near Cledonis suffered backflow issues when the river rose, so the great mages of the ancient city installed magical valves at several places in the sewer’s length to prevent this.

Each valve appears as a blue shimmering wall, visible with any amount of light that allows a creature to see. The “wall” encompasses the width of the sewer(and extends an additional 20 ft. to each side, if they attempt to tunnel around it). In the direction of flow, the valve counts as 5 ft. of difficult terrain, but otherwise has no effect. In the opposite direction, its effects are much more dramatic.

* Water and watery liquids cannot flow, and will be stopped as if by a Wall of Force spell.

* A solid item or creature containing substantial amounts of water (biological creatures, fresh food, etc.) that attempts to travel through the valve will only be able to move 5 ft. in a turn, regardless of movement speed, and will suffer 2d8 necrotic damage if any part of it goes through the valve. If the entire object or creature moves backwards through the valve, it suffers damage as if from the Blight spell. A creature will also suffer exhaustion as if they had gone a day without water (PHB 185).

* Low-water items (dried rations, seasoned wood, etc.) will be only subtly affected, with the valve requiring 20 feet of movement to pass, and a wisp of steam or a drop of water falling off of them as they pass backwards through the valve. (DC 10 Perception check to see this)

* Waterless items (metal, glass, etc.) will treat the valve as 5 ft. of difficult terrain in each direction, with no other effects.

The valve primarily acts on the outer surface of an object, however, so a watery object or creature within a dry shell will have substantial protection from the valve’s effects. An all-encompassing shell (e.g., full plate armour, items in a sealed glass vial) will halve the damage taken and prevent exhaustion. A large, but not all-encompassing, shell (e.g., goods inside a leather backpack, a creature that has improvised a relatively complete cover around itself) will give advantage on the Blight save, and reduce the exhaustion effect to that of a day with half-rations of water.

The valve’s effect can be suppressed by the Dispel Magic spell, as if it were an 8th level spell. If it is suppressed in this way, it will reappear 24 hours later. Truly destroying the valve requires excavating the entire area of effect and successfully dispelling all twelve anchor points within the same 24-hour period.