Go to Part 1

PIECE BY PIECE

In the Daedalus Robotics Lab, a haunted screwdriver curses anyone touching it to begin disassembling the world… starting with people.

Writing out the premise of Piece by Piece in such plain terms might make it sound a little goofy, but in practice this adventure works really well. The Daedalus Lab is a well-structured location crawl stocked with clues that can unravel a decade-old mystery. A well-rounded cast of NPCs fleshes the whole thing out with some nice character moments and emotional stakes (and gives you some raw meat to target when the shit hits the fan).

The only real weakpoint here is the scenario hook, which looks like this:

The Daedalus Robotics Lab is in lockdown after personnel were fatally compromised in a random incident. Reports are linking the events to a work tool found at the scene, now classified as Artifact 21. Further details are undisclosed.

Daedalus Robotics Lab’s parent company, Jensen-Hung, is excited to offer an attractive opportunity to any self-motivated freelancers in the sector! Taking on the important role of Temporary Maintenance Crew, contractees are tasked with retrieving Artifact 21 for analysis. Caution is advised; discretion is enforced.

Your crew must investigate the lab, identify ARTIFACT 21 and retrieve it.

At first glance, this all seems fine. Unfortunately, that’s part of the problem because it will lure you into a false sense of security. In reality, there are multiple layers of problems here:

- Given the facts presented in the rest of the module, Jensen-Hung should know that “Artifact 21” is the screwdriver. So why are they asking the PCs to identify it?

- If Jensen-Hung owns Daedalus, why are the PCs being sent in undercover as a maintenance crew?

- The hook suggests that Jensen-Hung was notified of what happened (by an android named Curtis), resolved to retrieve “Artifact 21,” put up a job posting, waited for the PCs to respond to it, hired the PCs, and then sent the PCs to the lab. But both the current situation at Daedalus Robotics Lab and the timeline of events provided by the adventure makes it clear that Curtis’ call to Jensen-Hung actually happened maybe fifteen minutes ago.

These issues — particularly with the timeline — caused a lot of headaches for me the first time I ran the adventure. The players really struggled to figure out the timeline (and, therefore, the mysteries connected to that timeline) because they immediately realized that it didn’t make any sense.

As written, I give Piece by Piece a C+ (okay, with some nice bits). But it’s a B (recommended) or B+ experience if you make a couple simple tweaks:

- I would avoid telling the PCs that an item is responsible for the incident. It really weakens the sense of enigma about what’s happening onsite. (It will also likely cheapen the ending.)

- The timeline is weird because there’s no meaningful gap between Curtis calling Jensen-Hung and the events that are happening when the PCs show up; but obviously there must be a gap of time in which Jensen-Hung contacts the PCs and hires them. Shorten the latter by having Jensen-Hung reach out to the PCs (instead of posting an open ad). Lean into the former by creating a gap: Curtis called Jensen-Hung and was instructed to download all the research data and then wait for extraction. So he did that and then, as described in the adventure, went to the Lobby and met with Dr. Ojo, who is now repairing the minor injury he received. (I would also skip the bit where Curtis supposedly told Ojo that Martina was brutally murdered, but then Ojo just doesn’t do anything about that… because that’s also weird.)

And that should get you sorted.

It might also be useful to note that, if the PCs realize that the screwdriver is responsible, then the finale of the adventure will likely resolve very easily as they all make a point of not touching it. This works well if it’s earned; less so if that knowledge is just handed to them. You really want the finale to be various people getting possessed by the screwdriver and creating chaos, and it’s even better if that includes the PCs.

(Along these same lines, I encourage you to have a PC who gets stabbed by the screwdriver have it get stuck in their shoulder. This will create a natural vector for someone to grab it and pull it out.)

But I digress!

As noted, I recommend this adventure, particularly with the tweaked hook. DG Chapman provides a very satisfying experience at the table.

GRADE: B-

TERMINAL DELAYS AT ANARENE’S FOLLY

The centerpiece of Terminal Delays at Anarene’s Folly is the Creation Device — a cheap knockoff loving homage to the Genesis Device from Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, capable of rapidly terraforming an entire planet. (Which is, if you think about it, quite horrific from a certain point of view.)

Unbeknownst to the PCs, the Creation Device is currently in their ship’s hold, concealed in the false bottom of a crate of hydroponics equipment that they’ve been hired to deliver. When they arrive at the space station Anarene’s Folly to refuel, however, the station personnel either know or discover that they have the Creation Device and mount an operation to steal it. It’s time for a reverse heist!

I’ve actually found this to be a tough adventure to review. I like the concept, and Ian Yusem’s execution includes a lot of realty nice material. But for some reason, I just can’t seem to get the whole thing to gel.

Here’s an example of what I mean: The core structure of Anarene’s Folly is the Station Escalation Timeline. This consists of seven numbered steps, and the idea is that you trigger one step for every twenty minutes of real time at the table. But the first two steps are:

- The PCs are hailed by dock control and told there’s a wait time before they can dock.

- The PCs are asked to transfer control of their ship to the station AI. (And then the AI begins hacking the ship’s computer, initiating the complementary Systems Hack Timeline.)

On the one hand, this makes sense. On the other hand, what actually happens in the twenty minutes between Step 1 and Step 2?

Anarene’s Folly does give you a roleplaying profile for Simon Wainwright, the Space Traffic Controller, and a Small Talk Table to provide raw fodder for that conversation. I’m looking at that and it just seems interminable.

And it feels like the Station Escalation Timeline, the Systems Hack Timeline, the Gaslighting Table, and the Marine Kill Team Tactical Plan are all modeled as independent, modular components so that they can interface dynamically in actual play…

… but it doesn’t seem like they actually do? The central Station Escalation Timeline is a long slow burn, triggering the Systems Hack Timeline, which has a slow burn of its own until the station AI gets to the point where it can start triggering the Gaslighting Table, which consists of various fake malfunctions and false alarms. These aren’t really independent variables; they’re all linked in chain (although each can be hypothetically disrupted separately).

So you’ve got the PCs running around doing random chores, and maybe at some point they get suspicious and maybe that’s meant to mix things up? But then you start looking at the “flexible” tools that you can use to respond to the PCs, and it seems like they aren’t actually that flexible. If they’re disrupted, the timelines mostly just break. Plus, the PCs don’t seem to have any real options because there’s no clear vector by which they can figure out that the Creation Device is in their hold, plus you’re supposed to kinda railroad them into Anarene’s Folly without enough fuel to reach another station. And then there’s some weird and unexplained stuff. (At one point, for example, Anarene’s Folly abruptly evacuates all nonessential personnel from the station for no discernible reason.)

So, as I say, it feels like Anarene’s Folly is well-stocked with cool tools for running a flexible adventure that responds dynamically to the PCs’ actions. Maybe it is and I’m just missing something. But I just can’t quite seem to grok this one.

GRADE: C

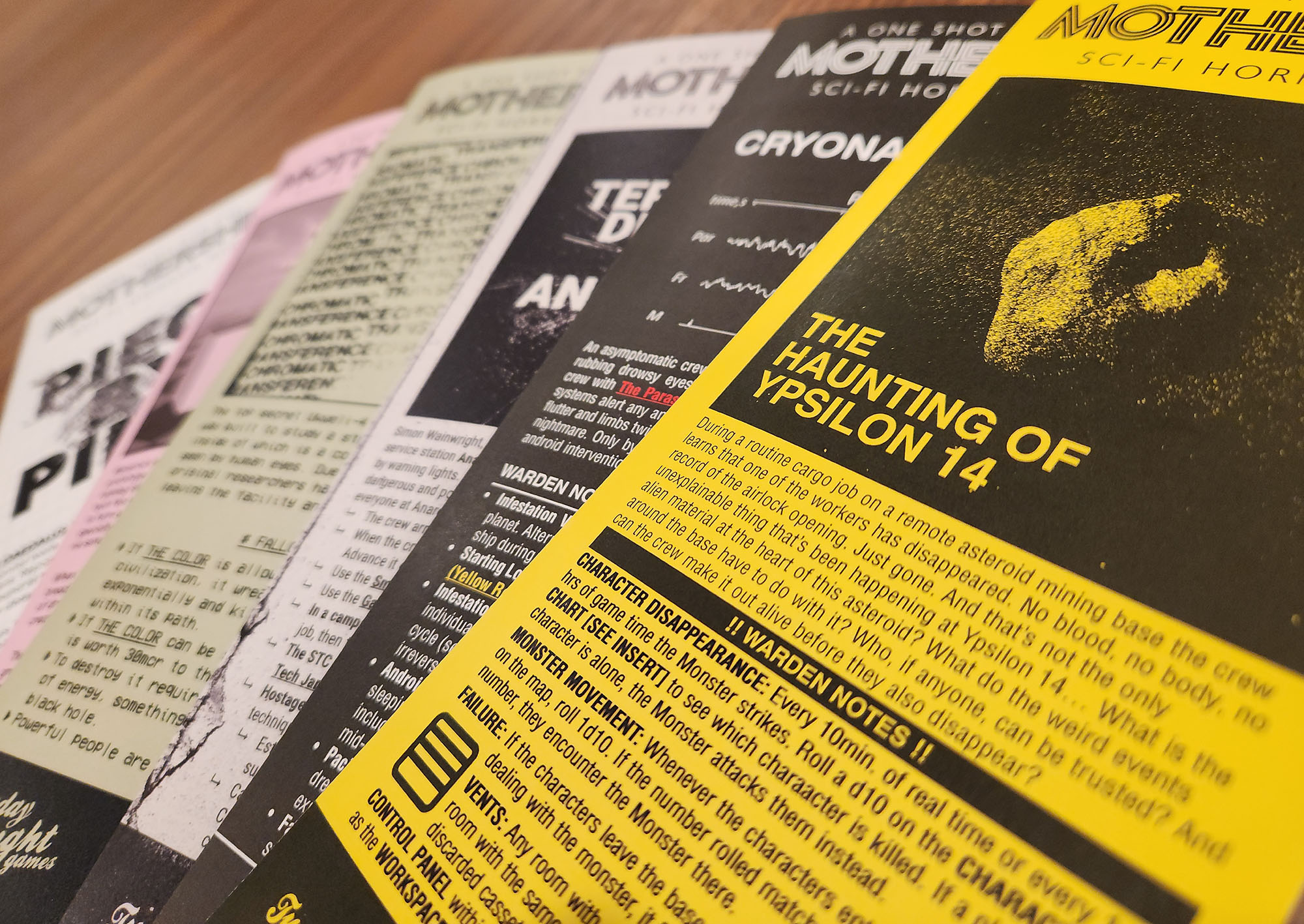

THE HAUNTING OF YPSILON 14

The Haunting of Ypsilon 14 is set on an asteroid where miners have accidentally woken up an alien who was resting in suspended animation. The alien is hostile (of course!) and mayhem ensues!

The first thing you’ll note about the adventure is that it presents the mining base as a flowchart, unifying key and map together rather than a more literal depiction. This largely works, although some unkeyed map symbols may leave you scratching your head.

DG Chapman does several things that elevate this above a simple evening of “there’s an invisible alien eating people” affair.

First, the design of the station is very satisfying. There’s a variety of environments and the areas have been spiked with lots of little fun easter eggs and clues that reward exploration.

Second, Chapman has again included a robust supporting cast. Their details can be a little sketchy, but in practice they develop well in actual play.

Third, in addition to the alien monster, there’s also the Yellow Goo: A medical nanotechnology that heals aliens, but interprets human bodies as being very, very sick and in need of “curing.” This adds a second vector to the scenario’s horror, helping to mix things up and keep it fresh.

Once again, the weak point here is the scenario hook, which is a little shallow and can cause PCs to kind of skim off the surface of the adventure instead of really diving in. (I’ve written a separate article on How to Prep: The Haunting of Ypsilon 14 that you may find useful here.) This is balanced, however, by the supreme ease with which this module can be slid into any Mothership campaign or framed up as the perfect introductory module.

A lot of Mothership GMs will tell you they got started by running The Haunting of Ypsilon 14, and there’s a good reason for that: This is just a rock solid adventure. Easy to run. Easy to enjoy.

GRADE: B

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

These trifold adventures are Mothership’s secret weapon, and in large part their strength is collective: None of them are the greatest adventure you’ve ever seen, but they are consistently good. They also do a good job of showcasing the breadth of what Mothership is capable of.

Individually, therefore, each is pretty good and I recommend all but one of them. As a collection, on the other hand, I find that they demand my attention and insist that I run them as part of a Mothership campaign as soon as possible.

Which I will be more than happy to do.

FURTHER READING

Reviews: Mothership Adventure Sphere

A guide to grades at the Alexandrian.