A couple years ago I talked about the way in which “modern” encounter design had crippled itself by fetishizing balance, resulting in encounters which were less flexible, less dynamic, and less interesting. This trend in encounter design has, unfortunately, only accelerated. More recently, I’ve started referring to it as My Precious Encounter(TM) design — a design in which every encounter is lovingly crafted, carefully balanced, painstakingly pre-constructed, and utterly indispensable (since you’ve spent so much time “perfecting” it).

Around that same time, I was also talking about the Death of the Wandering Monster: The disconnect between what I was seeing at the game table and the growing perception on the internet that wizards were the “win button” of D&D. Even a casual analysis indicates that the “win button” wizard only worked if you played the game in a very specific and very limited fashion. Given all the other possible ways you could play the game, why were people obsessing over a method of substandard play that was trivially avoided? And, in fact, obsessing over it to such a degree that they were willing (even desperate) to throw the baby out with the bathwater in order to fix it?

The root problem which links both of these discussions together are the Armchair Theorists and CharOp Fanatics.

Now, let me be clear: Good game design is rooted in effective theory and strong mathematical analysis. Any decent game designer will tell you that. But what any good game designer will also tell you is that at some point your theory and analysis have to be tested at the actual gaming table. That’s why solid, effective playtesting is an important part of the game design process.

The problem with Armchair Theorists is that their theories aren’t being meaningfully informed or tested by actual play experiences. And the problem with CharOp Fanatics is that, in general, they’re pursuing an artificial goal that is only one small part of the actual experience of playing an RPG.

Among the favorite games of the Armchair Theorists is the Extremely Implausible Hypothetical Scenario. The most common form is, “If we analyze one encounter in isolation from the context of the game and hypothesize that the wizard always has the perfect set of spells prepared for that encounter, then we can demonstrate that the wizard is totally busted.”

Let’s call it the Spherical Cow Fallacy: “First, we assume a spherical cow. Next, we conclude that cows will always roll down hills and can never reach the top of them. Finally, we conclude that adventures should never include hills.”

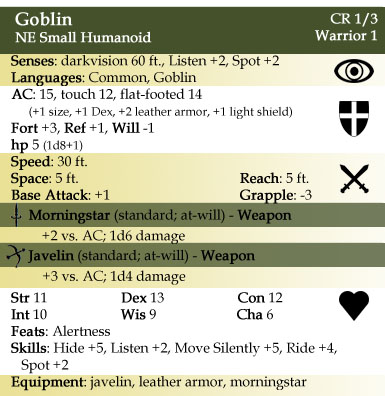

Ever seen the guys claiming that wizards render rogues obsolete because knock replaces the Open Locks skill? That’s a spherical cow. (In a real game it would be completely foolish to waste limited resources in order to accomplish something that the rogue can do without expending any resources at all. It’s as if you decided to open your wallet and start burning $10 bills as kindling when there’s a box of twigs sitting right next to the fireplace.)

Another common error is to implicitly treat RPGs as if they were skirmish combat games. Ever notice how much time is spent on CharOp forums pursuing builds which feature the highest DPS (sic)? Nothing wrong with that, of course. But when you slide from “this is a fun little exercise” to believing that a class is “br0ken” if it doesn’t deliver enough DPS, then you’re assuming that D&D is nothing more than a combat skirmish game.

Another variant is Irrational Spotlight Jealousy. A common form of this is, “The rogue disables the trap while everyone sits around and watches him do it.” (In a real game, traps are either (a) more complicated than that and everyone gets involved or (b) take 15 seconds to resolve with a simple skill check. The idea that a game grinds to a halt because we took 15 seconds to resolve an action without everybody contributing is absurd.)

Then there’s the Guideline as God, which becomes particularly absurd when it becomes the TL;DR Guideline as God. This is the bizarre intellectual perversion of the CR/EL system I described in Revisiting Encounter Design in which the memetic echo chamber of the internet transformed some fairly rational guidelines for encounter design into an absolute mandate that “EL = EPL”. (For a non-D&D example, consider a recent thread on Dumpshock which featured a poster who considered the statement “when a corporation or other needs someone to do dirty work, they look to the shadowrunners” to be some sort of absolute statement and was outraged when a scenario included a corporation performing a black op without using shadowrunners.)

And when these fallacies begin feeding on each other, things get cancerous. Particularly if they become self-confirming when designers use their faulty conclusions as the basis for their playtests. Playtests, of course, would ideally be the place where faulty conclusions would be caught and re-analyzed. But playtests are like scientific experiments: They only work if they’ve been set-up properly.

For example, 4th Edition suffers as a roleplaying game because so much of the game was built to support the flawed My Precious Encounters(TM) method of adventure design. Proper playtesting might have warned the designers that they were treating 4th Edition too much like a skirmish combat game. But unlike the playtesting for 3rd Edition (in which playtesters were given full copies of the rules and told to “go play it”), the reports I’ve read about 4th Edition playtesting suggest that the majority of playtesters were given only sections of the rules accompanied by specific combat encounters to playtest. Such a playtest was designed to not only confirm the bias of the design, but to worsen it.

(Not a problem, of course, if you believe that D&D should be primarily a skirmish combat game.)

Personally, I think it’s time for a slaughtering of these spherical cows. Neither our games nor our gaming tables are well-served by them.