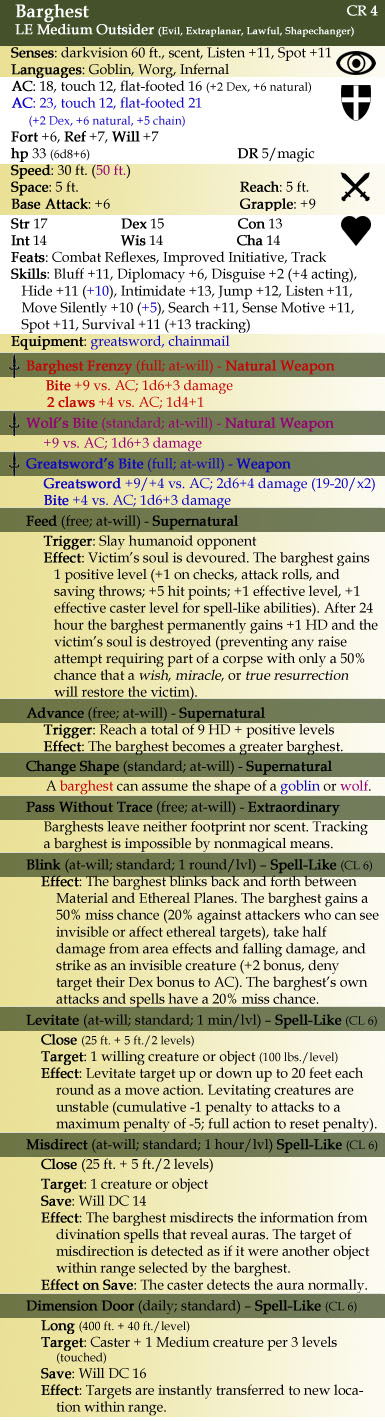

Yesterday I talked about Robert J. Schwalb’s theory that 4th Edition’s formatting was a barrier for players of 3rd Edition.

Yesterday I talked about Robert J. Schwalb’s theory that 4th Edition’s formatting was a barrier for players of 3rd Edition.

It is interesting to note, however, that Schwalb is not the only designer from Wizards publicly trying to figure out what went wrong in converting 3rd Edition players into 4th Edition players. Earlier in the week, Mike Mearls actually argued for genericizing the D&D trademark in the name of recognizing that D&D isn’t a game, but rather an experience that we all share regardless of which rules we use. (Or possibly he’s arguing that it doesn’t matter what we’re playing, as long as it has the “Dungeons & Dragons” trademark on it. The essay is a little vague in its kumbaya.)

Ultimately, of course, the problem is that they had a specific game that had been revised multiple times but maintained its core gameplay from 1974 to 2008. And then, in 2008, they stopped selling that game. Until they accept that, they aren’t going to find the solution they’re groping for. (To be fair, even if they do realize that this is the problem, there’s not much they can do about it: Publishing a new edition any time before at least 2015 would completely poison their market. And writing off the development costs of the DDI as a loss by obsoleting the current platform would basically amount to corporate malfeasance.)

NEW vs. CLASSIC

The comparison to “New Coke” is often made here, but it’s not entirely apt: This is more akin to the Coca-Cola Corporation giving its original formula to somebody else before stopping their own production of it and then using the “Coke” trademark for New Coke. The result was completely predictable: WotC kept the people who were loyal to the trademark and they kept the people who prefer New D&D to Classic D&D. They lost everybody else.

How bad is it? Well, there are multiple reports that Paizo’s Pathfinder is either tying or beating Wizard’s 4th Edition sales. If Pathfinder represented the totality of 3rd Edition players who didn’t migrate to 4th Edition, that would still be bad news for Wizards. But, of course, Pathfinder doesn’t. How many 3rd Edition players are just continuing to play with their existing 3rd Edition manuals?

(It would be nice to imagine that Pathfinder‘s success can be attributed to the RPG market simply growing, of course. But there doesn’t seem to be any evidence for such a massive increase in the market.)

WHAT WENT WRONG

When consumers are faced with an upgrade, there’s always going to be some portion of the customer base that says, “Nah. I’m good with what I’ve got.” (This applies beyond RPGs: Look at the varying success of Windows Vista and Windows 7 at winning over existing Windows customers.) In the case of D&D, the two most effective transitions in the history of the game were the transition from OD&D to AD&D and the transition from AD&D2 to D&D3.

When consumers are faced with an upgrade, there’s always going to be some portion of the customer base that says, “Nah. I’m good with what I’ve got.” (This applies beyond RPGs: Look at the varying success of Windows Vista and Windows 7 at winning over existing Windows customers.) In the case of D&D, the two most effective transitions in the history of the game were the transition from OD&D to AD&D and the transition from AD&D2 to D&D3.

In my opinion, both of those transitions were effective because (a) they addressed perceived shortcomings in the existing rules; (b) they worked to form a bridge of continuity between the old edition and the new edition; and (c) they were effective at reaching out to new customers.

Now, the actual methods by which these goals were accomplished were radically different. AD&D (a) aimed to codify a more “official” version of the game while also expanding the detail of the rules in an era when “more realism” and “more detail” were highly prized. It was launched with a Monster Manual that was (b) designed to be used with the existing OD&D rules (by the time the first PHB came out, a sizable chunk of the customer base was already using AD&D products in their OD&D games). And it was released hand-in-hand with a Basic Set that (b) remained highly compatible with the 1974 ruleset and (c) offered a mainstream, accessible product for attracting new customers.

D&D3, on the other hand, (a) radically revised a game that was perceived as clunky and out-of-date, which allowed them to (c) reach out to a large body of disillusioned ex-customers. They simultaneously (b) released conversion guides and used a massive, public beta testing period to get large numbers of existing players onboard with the changes before the game was even released.

The conversion to D&D4 failed for several reasons.

First, no effort was made form a bridge between the old edition and the new edition. (A crazy French guy screaming “Ze game remains the same!” like some sort of cultic mantra notwithstanding.) In fact, WotC went out of their way to insist that there was no bridge between the editions.

Second, WotC was attempting to reach out to new customers. But I maintain that they made the fundamental mistake of trying to pull customers away from video games by competing with video games on their own turf. That’s just not going to cut it. If RPGs are going to be successful in the future, it will be because they emphasize their unique strengths. Tactical combat and prepackaged My Perfect Encounters(TM) aren’t going to cut it.

Finally, 2008 was misidentified as being another 2000.

In 2000 WotC was dealing with an overwhelmingly dissatisfied fanbase and responded with a new edition that largely addressed that dissatisfaction without overstepping the boundaries of its “mandate”. It wasn’t perfect. Plenty of people remained dissatisfied (or hadn’t been dissatisfied in the first place). But there were also a lot of people saying “3rd Edition looks just like my house rules for AD&D” or “it’s exactly what I’ve always wanted D&D to look like”, and success followed.

In 2008, I think it’s clear that WotC thought they had a similar level of overwhelming dissatisfaction. But either they didn’t or their sweeping and fundamental changes to the game exceeded the “mandate” of that dissatisfaction. Or both. (Personally, I suspect they were misled by the echo chamber of the ‘net and a corporate decision to prevent OGL support for 4th Edition. They tried to solve “problems” that most players weren’t actually experiencing and simultaneously “fixed” them in an unnecessarily excessive fashion.)

In some ways this takes us back to the “New Coke” metaphor: The taste tests for New Coke indicated it would be a huge success. But the taste tests were fundamentally flawed: They were “sip tests”. And in sip tests the smoother, sweeter taste of New Coke won. But nobody buys their soda by the teaspoon; they buy it by the can.

4th Edition radically overhauled D&D’s gameplay in order to respond to complaints driven by CharOp specialists, armchair theorists, and other lovers of spherical cows. For a lot of people on the ground, the game didn’t have those problems and 4th Edition was a solution in search of a problem.

THE OGL AND SRD

WotC’s corporate culture had clearly turned against the OGL by 2008. They no longer saw a massive network maintaining interest in their game and generating new customers who were all funneled back into their core products. Instead, they saw an entire industry profiteering on their IP.

The argument of whether or not WotC was right or not can be saved for another time. (Although I will note that every scrap of evidence I’ve seen indicates that the strategy works both in the RPG industry and outside of the RPG industry. D&D3, Pathfinder, and the OSR community all seem to have flourished under it as well.)

But given the existence of the OGL, the decision to stop making Classic D&D and start making New D&D was a disastrous one. The goal appears to have been to create an edition with enough fundamental incompatibility that the OGL couldn’t be used to support it, but the practical effect was to leave the largest network of material supporting an RPG in history all pointing towards a giant void.

A void into which it was absolutely trivial for someone to step.

THE MISSED OPPORTUNITY

My biggest regret is that I feel WotC missed an opportunity. There are, in fact, some significant problems with 3rd Edition.There are key abilities in 1st to 10th level play (polymorph, for example) that need to be fixed. And from 12th to 20th the game begins to crack and then break down. These problems require an overhaul of the basic foundations on which the game is built.

It is, however, possible to fix these problems without nuking the core gameplay which has been successful since 1974.

WotC chose the nuke option.

Meanwhile, Paizo couldn’t make those changes with Pathfinder while simultaneously stepping into the void vacated by WotC.

That’s the missed opportunity here: WotC had the chance to polish and improve Classic D&D; to take the next step with the game. Instead, they side-stepped and gave us New D&D instead.

Looking ahead, I think the time period right around 2014-2015 will be potentially very interesting: WotC would be able to theoretically roll out a new edition, and the question will be whether they’ll stick with improving New D&D or if they’ll try to revert to Classic D&D. (Or do something else entirely.) Meanwhile, if Paizo continues to solidify (or even build) their market share, then right around that same time they’ll potentially be in a position to attempt a 2nd Edition of Pathfinder that can be more radical in its efforts.

On the other hand, maybe not. The emerging long-tail economics combined with open licensing may mean that no revision of the 3rd Edition ruleset will ever be able to break 3rd Edition’s network of players and support material. The D&D trademark might have been able to do it in 2008, but in decoupling the D&D trademark from Classic D&D WotC seems to have created a massive player base that no longer has any loyalty to that trademark. The horse may have left the barn for good.

You know the story I never need to read again? It’s the one where some vigilante comes to Gotham City and says, “I’m going to use guns and kill criminals. ‘Cause I’m a bad-ass and I’ve got the guts to do what Batman can’t.” And then, ya know, something goes wrong: A kid or a cop gets caught in the crossfire. It turns out the “criminal” was actually innocent. Commissioner Gordon won’t stand for it. Batman says, “Stop being a dick.” Whatever.

You know the story I never need to read again? It’s the one where some vigilante comes to Gotham City and says, “I’m going to use guns and kill criminals. ‘Cause I’m a bad-ass and I’ve got the guts to do what Batman can’t.” And then, ya know, something goes wrong: A kid or a cop gets caught in the crossfire. It turns out the “criminal” was actually innocent. Commissioner Gordon won’t stand for it. Batman says, “Stop being a dick.” Whatever.