Studying the lost authors of early fantasy and science fiction is often a humbling lesson in the fickleness of fate. Authors who were just as talented and creative as Robert E. Howard, Isaac Asimov, H.P. Lovecraft, or Ray Bradbury have been largely forgotten by later generations. Nor can their modern anonymity be explained due to a lack of influence or popularity — in many cases they were more influential and popular during their publishing careers than contemporaries who remain well-known today.

Studying the lost authors of early fantasy and science fiction is often a humbling lesson in the fickleness of fate. Authors who were just as talented and creative as Robert E. Howard, Isaac Asimov, H.P. Lovecraft, or Ray Bradbury have been largely forgotten by later generations. Nor can their modern anonymity be explained due to a lack of influence or popularity — in many cases they were more influential and popular during their publishing careers than contemporaries who remain well-known today.

I first became aware of this phenomenon in the mid ’90s when Kurt Busiek pointed me towards Mutant, a collection of stories written by Henry Kuttner that had played a major influence in the creation of the X-Men by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Kuttner, I discovered, had influenced an entire generation of science fiction authors. In 1946, at the height of the Golden Age of Science Fiction, fans were asked to choose between Isaac Asimov, Theodore Sturgeon, A.E. Van Vogt, and a dozen others to name one of them as the World’s Best SF Author. They chose Kuttner. Kuttner married C.L. Moore, who had already become known as the First Lady of Science Fiction. The two of them writing together created an amazing corpus of work at such an incomprehensible pace that it required more than twenty pseudonyms to publish it all.

Kuttner died in 1958. Moore retired form writing. And for half a century their works slowly faded into obscurity. Discovering these lost jewels of speculative fiction (including Fury, which remains one of my Top 10 Science Fiction Novels of all-time) was a real wake-up call.

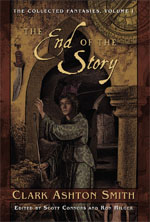

In the past 10 years or so the information-deluge of the Internet coupled with global access to catalogs of used books and small press collections have started to return many of these Lost Authors to the light. Among them is Clark Ashton Smith.

I originally encountered Smith’s writing about a decade ago when I found a collection of his Zothique stories (set on the last continent of a dying Earth). These stories made me want to read more, but it proved devilishly difficult to find more of Smith’s writing in print. (At reasonable prices, anyway.)

So when I heard several years ago that Night Shade Books was planning to publish a five volume series collecting all of his stories, I immediately signed up for a subscription. Unfortunately, the series has proven to be absurdly lethargic in the pace of its releases. In fact, it has yet to be completed (although there is great hope that the last volume will appear later this year).

This has not prevented me, however, from sitting down recently to enjoy Volume 1: The End of the Story.

The series presents Smith’s writing in the chronological order of its composition, starting in 1925 with “The Abominations of Yondo”. This was a story that I had read before, but had no idea that it was Smith’s first stab at speculative fiction. It is a remarkable freshmen work, effortlessly conjuring forth an alien and fantastical environment of an utterly unearthly character. This, in fact, becomes Smith’s defining strength as an author. The alien planets, alternate universes, and ancient epochs in which he sets his stories are not merely distant in time or space; they are utterly alien in their character.

The sand of the desert of Yondo is not as the sand of other deserts; for Yondo lies nearest of all to the world’s rim; and strange winds, blowing from a pit no astronomer may hope to fathom, have sown its ruinous fields with the gray dust of corroding planets, the black ashes of extinguished suns. The dark, orblike mountains which rise from its wrinkled and pitted plain are not all its own, for some are fallen asteroids half-buried in that abysmal sand. Things have crept in from nether space, whose incursion is forbid by the gods of all proper and well-ordered lands; but there are no such gods in Yondo, where live the hoary genii of stars abolished and decrepit demons left homeless by the destruction of antiquated hells.

“… the gray dust of corroding planets, the black ashes of extinguished suns.” Could anyone mistake such a place as merely being the analog of some Earthly wasteland?

The strength of “The Abominations of Yondo” aside, however, Smith’s talent did not spring forth fully formed from the brow of Zeus. And this volume, containing as it does Smith’s earliest efforts, has a fair share of formulaic work: “The Ninth Skeleton”, “Phantoms of the Fire”, and “The Resurrection of the Rattlesnake”, for example, are paint-by-number horror “shockers”. “The Last Incantation” and “A Night in Malneant” are thin and predictable morality tales.

But even in these weaker tales there is a vividness of description and a poetic quality of verse which raises them, however slightly, above similar fare. (With the exception of “Phantoms of Fire” which is simply a bad story by any accounting.) The dead streets of Malneant, in particular, continue to echo through the chambers of my mind many long nights after I finished the tale.

There are, similarly, far too many tales starring self-inserted writers of pulp fiction and poverty-stricken poets. But here, again, Smith manages to use this weak conceit to good effect from time to time. For example, “The Monster of the Prophecy” is the tale of a struggling, poverty-stricken poet who is plucked off the street by an alien visitor from a distant planet. Not only does the poet’s writing become famous, but he himself is given the opportunity to adventure among the stars. In synopsis, the tale sounds like ripe fodder for a Mary Sue. But, in practice, Smith sidesteps the abyss and produces a memorable (if somewhat flawed) tale.

If Smith suffers from a consistent flaw throughout this volume, it is the weakness of his plots and the forgettable quality of his characters. In some ways, however, this flaw stands in complement to his strengths: His tales often read as travelogues of the bizarre, featuring cipherous everymen who serve as the readers’ empty avatars as they wander through the alien vistas.

In many ways, the stories reveal Smith’s true passion as a poet: Many read like tone poems, and I found the book most enjoyable when I chose to sample its contents instead of trying to barge from one tale to the next from front cover to back.

I am curious to see, as I continue to work my way through Smith’s oeuvre, whether his poetic mastery of language and his mind-blowing descriptions of fantastical landscapes will become wedded to plots of substance and characters that you can care about.

On the other hand, I feel this review will be read as more negative than it perhaps should be. In addition to “The Abominations of Yondo” and “The Monster of the Prophecy”, this collection also contains “The Venus of Azombeii” (in which the characters do explode off of the page with a surprising passion), “Thirteen Phantasms” (in which a morality tale is twisted and turned into something unpredictable and beautiful and special), “The Tale of Satampra Zeiros” (which could be described as capturing all the vigor and spirit of Howard’s Conan stories and wedding it to Smith’s fantastical vision, except for the fact that it was written three years before Conan appeared), “The Metamorphosis of the World” (which, although flawed in parts, is majestical in its scope), “Marooned in Andromeda” (an excellent entry in the travelogue category), and “The Immeasurable Horror” (featuring one of the most memorable depictions of the jungles of space opera Venus). And these are all excellent tales which anyone might be well-advised to read.

Perhaps more importantly, Smith’s eye for the fantastic is utterly unique. The influence of his writing has been widely felt, but if you haven’t read his own work, then you’ve never read anything quite like Clark Ashton Smith.

GRADE: B+

Clark Ashton Smith

Published: 2007

Publisher: Night Shade Books

Cover Price: $25.00

ISBN: 1597800287

Buy Now!