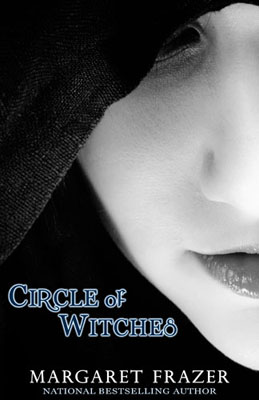

I’d like to welcome Margaret Frazer and her Midwinter Blog Tour for Circle of Witches, which is stopping by the Alexandrian today for a tour of the book’s cover.

I’ve previously worked with Ms. Frazer in designing new covers for the e-book editions of her award-winning short stories and Dame Frevisse Mysteries, but Circle of Witches proved a new and unique challenge. First, it required the creation of an entirely new product identity that would distinguish it from her previous work. Second, the book itself is an interesting enigma that lies at the intersection of many genres while belonging properly to none of them.

| MISTY MOORS. ANCIENT SECRETS. FORBIDDEN PASSIONS. Her mother had always been afraid. That’s what Damaris remembered. From the time she was a little girl until the day her mother died, she had seen the fear in her eyes. But now she understood. Now she was afraid, too. Young Damaris wanted more than anything to be happy at Thornoak, the ancient manor owned by her aunt and uncle. Adventuring through the wide, open beauty of the Dale in the company of her rambunctious cousins she rediscovered a joy she had thought lost with the death of her parents. And in the deep, storm-tossed eyes of Lauran Ashbrigg she was surprised to find an entirely new emotion. But even under the warm and inviting sun, Damaris is chilled by the undeniable fact that the family which claims to welcome and love her is hiding truths from her: The truth of the Lady Stone. The truth of the Old Ways. The truth of moon and star and witchcraft. The truth of her mother’s death. |

In the course of creating the cover for Circle of Witches, several dozen distinct images were created of which only a sampling will be shown here. My earliest efforts focused on trying to capture the deep and disturbing beauty of the Yorkshire dales which capture the heart and imagination of both Damaris and the reader. But what I quickly discovered was that the true beauty of the dales lies in their vast openness: The minute you to capture or contain them in a 6″ x 9″ cover, the very thing which makes them breathtaking seems to vanish.

My attention, therefore, turned to Damaris herself. Let’s start with this image.

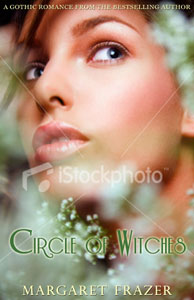

Here you can see an early effort to find a typographical identity for the title. (The font for Margaret’s name actually carries over from her other books, providing some continuity across all her works.) This work had begun, of course, with the early mock-ups of dale-oriented covers and the partial script-work was meant to capture the Jane Austen-like feel the novel had for me.

But I was ultimately dissatisfied with this particular typography, particularly as I moved into heroine imagery for the cover itself.

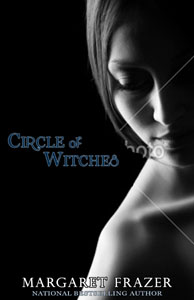

So here you can see the iterative evolution of what would eventually become the title — the flourish of the “s” in “Witches” being joined by a matching flourish in the “r” of “Circle”.

I’m actually very partial to this particular cover, but it simply proved too sultry for Circle of Witches: Those of you who have already read the book will know that this is definitely not Damaris.

So here’s something on the other end of the scale. This was another of my favorites, and ended up being on the final “short list” of four covers that were sent out to Margaret’s beta readers for feedback. You can see me experimenting with a very different title typography.

One concern with this cover was that it had gotten too “soft”, so we tried out the tagline “A Gothic Romance from the Bestselling Author” to provide some contrast.

On the other hand, I think Circle of Witches is one of those great books that will reward being revisited at different times during your life. The book will thrill you as a young adult; delight you in your thirties; and give you cause for reflection when you’re older. So I wanted a cover that could draw in young readers to begin that process.

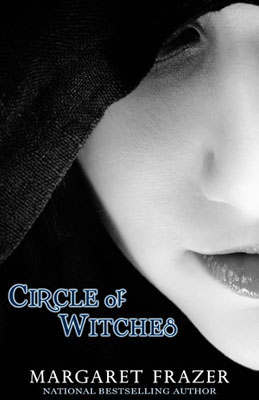

This is the cover around which I conceptualized and essentially cemented the design elements that would define what the final cover would look like. But while I felt the image was good, it wasn’t great. Which led me to track down the cover image that appears on the final book and remix the design elements from this cover into the new composition.

But even when that work was done, I didn’t actually realize that I’d nailed it. I generated several more options, including this one:

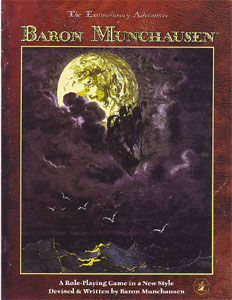

This is another one of my favorites to emerge from this design process and it was the run-away favorite of people who had not yet read the book. But once people had read the book, the anachronistic discord between this imagery and the novel itself led many of the people who had championed it to instead veto it vehemently.

This created an interesting debate: The primary purpose of a cover, of course, is to sell the book. If this was the best cover for accomplishing that, the fact that people didn’t like the cover after reading the book might, ultimately, be irrelevant. If we hadn’t had another strong option, there’s a chance that such an argument might have prevailed. But there was also the case to be made that a cover like this could turn away people who would enjoy what the book actually had to offer. The false expectations it might create could also hurt the book even among people who would otherwise have enjoyed it.

And so, in the end, we turned to what had probably been inevitable all along:

I think it speaks well of the book that its rich depths are capable of evoking such a wide variety of covers. It’s a novel that I’ve enjoyed immensely over the course of several readings and I certainly think you’ll be rewarded if you pick up a copy, too.

As a final note, I do retain the copyright for the cover designs which were not used. If you have a book that you think they’d look perfect on, please drop me a line. And, of course, I’m also in the market to do original cover design work for other novels. My rates vary depending on the exact nature of the design work, but generally fall between $150 and $200. Contact me for details.

UPDATE: On the other hand, if you think you can do a better job than me there is a Cover Remake Contest being run over at the Authoress. Remix the cover or make an entirely original one and you can win a prize package. Check it out.