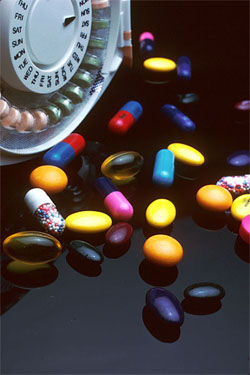

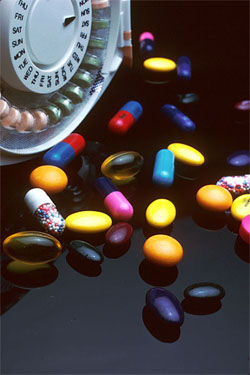

The basic function of a drug is similar to a poison: They have a type (contact, ingested, inhaled, injury), a Fortitude saving throw DC to resist their effect, an initial effect, and a secondary effect. However, drugs also have the following statistics:

The basic function of a drug is similar to a poison: They have a type (contact, ingested, inhaled, injury), a Fortitude saving throw DC to resist their effect, an initial effect, and a secondary effect. However, drugs also have the following statistics:

Buzz: The length of time the buzz from the drug lasts. The initial and secondary effects of the drug end when the buzz comes to an end. (For example, a PCP might inflict a Wisdom penalty as its initial effect and grant temporary hit points as its secondary effect. After the PCP’s buzz of 2d6 hours comes to an end, both the buzz and the temporary hit points go away.)

Addiction Threshold: The number of doses that must inflict the secondary effect of the drug before the user risks addiction. Once the user reaches the addiction threshold, they must make an addiction save. If a user goes one day without using the drug, reduce the current tally of doses by 1 to a minimum of 0.

Addiction DC: The DC of the Fortitude save required to resist addiction. On a failed save, the user becomes addicted to the drug (see below).

Recovery Threshold: If a user makes a number of successful withdrawal saves equal to the drug’s recovery threshold, their addiction is broken. They no longer suffer the effects of addition, but a recovering addict suffers a -4 penalty to future addiction saves against the same drug.

Compulsion DC: If a character addicted to a drug has the opportunity to take the drug, they must make a Will save against the drug’s compulsion DC. On a failed save, they must take the drug. If a character is currently suffering withdrawal, they take a -10 penalty on this saving throw. If the character is currently buzzed on the drug, they gain a +2 circumstance bonus on this saving throw for every dose of the drug currently affecting them.

ADDICTION

If a character becomes addicted to a drug, they must stay buzzed on the drug. When the buzz comes to an end, withdrawal begins. Withdrawal acts just like a disease with an incubation time of 1 day. Once per day, the victim must make a new saving throw against the withdrawal or suffer the withdrawal damage of the drug.

SAMPLE DRUGS

ABYSS DUST: Abyss dust is alchemically distilled from snakeweed (see below), although few associate the innocuous effects of snakeweed with this powerful narcotic. Abyss dust looks like ashes, with a rich black and gray color. It is administered through inhalation or smoking. Some hardcore users like to mix their abyss dust with snakeweed, claiming the snakeweed “takes the edge off” of some of the more extreme hallucinations.

Price: 1 gp

Effects: Inhaled DC 13, buzz 3d4 hours, initial effect Hallucinations (-4 on all action checks), secondary effect -1d4 Wisdom

Addiction: Addiction DC 13, threshold 3 doses

Withdrawal: Withdrawal DC 13 (fatigued, 2 Str, 1d4 Wisdom), Compulsion DC 10

BARBARIAN’S BLOOD: A recreational drug also known as “the red burn” and “veinglory”. Users of the drug are marked by a deep reddening of the skin and a significant protrusion of the veins. They experience a psychotropic dissociation in which physical pleasure is heightened and pain is experienced as pleasure.

Price: 2 gp

Effects: Ingested DC 13, buzz 1 hour, initial effect -2 penalty to Wisdom, secondary effect 2d4 temporary hit points

Addiction: Addiction DC 8, threshold 1 dose

Withdrawal: Withdrawal DC 15 (2 Str and 2 Con), Compulsion DC 15

SHADEBANE: Shadebane comes in the form of a pale, silver-grey powder. Water is added to this powder and it is then smeared on the skin. The user experiences hallucinations which give the impression of gifting them with visions from beyond the grave. Regardless of the truth or fiction of these visions, users of shadebane are intensely unpleasant for undead to approach. Undead within 5 feet of a shadebane user must succeed on a Fortitude save (DC 12) or become sickened (even if they would normally be immune to the sickened effect). Long-term users of the drug, however, become obsessive with death. They often begin collecting memento mori and are drawn to graveyards and others places of death. With prolonged use, these morbid obsessions can lead to suicidal, homicidal, or necromantic inclinations.

Price: 15 gp

Effects: Contact DC 13, buzz 1 hour, initial effect Hallucinations (-1 penalty to all action checks), secondary effect sicken undead (see text)

Addiction: Addiction DC 12, threshold 4 doses

Withdrawal: Withdrawal DC 12 (1d6 Wis, 1d6 Con), Compulsion DC 12

SNAKEWEED: The sunburst flower is found growing in many ancient ruins throughout the Serpent Islands. The trances produced by smoking the dried leaves and flowers of the plant became a popular, casual intoxication among the pirates of Freeport and spread to ports throughout the Southern Sea. When dried, the stuff is simply called snakeweed by most, and while it can be psychologically addictive it is relatively harmless by itself. When smoked, snakeweed produces a feeling of serene calm, a deadening of pain, and slight euphoria. Heavy doses produce an incapacitating euphoric stupor, and sometimes inspire dreams of shadowy, serpentine forms and vast cities beneath the waves. In Freeport, it is commonly used by the poorer citizens and sailors as an escape from the drudgeries of everyday life.

Price: 2 sp

Effects: Inhaled DC 11, buzz 1d3 hours, initial effect +1 to Will saves, secondary effect -1 Wisdom

Addiction: Addiction DC 5, threshold 12 doses,

Withdrawal: Withdrawal DC 5 (insomnia, -1 penalty to action checks), recovery threshold 5, Compulsion DC 5

This material is covered by the Open Gaming License.

This may only be interesting to me, but somebody pointed me in the direction of a story on Reddit featuring one of my gilted fiends.

This may only be interesting to me, but somebody pointed me in the direction of a story on Reddit featuring one of my gilted fiends.