In the Eclipse Phase setting, Artificial General Intelligences (AGIs) are the source of some deeply forged and bitterly raw prejudice: Their digital cousins the TITANs — seed AIs capable of recursive self-improvement — underwent a hard-takeoff singularity and shattered human civilization in a genocidal frenzy. The core rulebook states:

The vast majority of transhumanity blames the Fall on rogue seed AIs. As a result, any AIs that are not crippled or somehow limited from improving themselves — including the AGIs that were common and growing in number before the Fall — are completely illegal in many habitats or at least heavily regulated… Many transhumans consider AGIs and the TITANs that murdered their homeworld to be one and the same.

Since AGIs are also playable characters in Eclipse Phase, it can be vitally important to know where you can travel openly and where you need to fall back on smuggling and darkcasts if you’re going to go there at all. Unfortunately, this information is somewhat scattered and often unsatisfactory. (You have to reference various passages from the core rulebook, Sunward, and Rimward, and even then the information is frequently vague.) Reading between the lines and making a few inferences, however, we can draw up some general guidelines.

AGIs AND THE LAW

First, there’s a general spectrum that runs (from most severe limitations to least severe limitations): Jovian Republic, Lunar-Lagrange Alliance, Planetary Consortium, Morningstar Consortium, Titanian Commonwealth, and the Autonomist Alliance.

Within that spectrum, you can use these general guidelines:

Jovian Republic: AGIs are subject to summary erasure. Anyone creating, aiding, or abetting an AGI is subject to severe criminal penalties, including the possibility of execution for treason.

Lunar-Lagrange Alliance: AGIs are outlawed by most LLA communities; they will be banished or placed in cold storage depending on circumstance. Hypercorps or individuals creating AGIs are subject to heavy fines.

Planetary Consortium: Roughly 25% of Planetary Consortium polities ban AGIs completely (similar to the LLA). In other polities they are heavily regulated. AGIs are considered property by the Planetary Consortium and will never have citizenship rights. In addition to regulations by local polities, the Planetary Consortium as a whole has regulations governing the development and use of AGIs. Violations of these regulations are punished with heavy fines.

Morningstar Constellation: The Morningstar Constellation’s approach to AGIs is similar to the Planetary Consortium, but the regulatory oversight is significantly smaller and only 10% of Morningstar polities ban AGIs completely. (Very rare MC polities even grant AGIs citizenship, but citizenship in one Morningstar polity is no guarantee of your rights in another.)

Conservative Independents: This isn’t a specific political body, but a significant number of independent settlements (including some autonomist settlements) fall into this category. In these settlements, AGIs are considered full citizens but they sacrifice some of the normal rights of citizens. This most notably includes privacy: AGIs in these settlements will have their mesh access tightly monitored and their morphs/hardware specs routinely audited. They may even have to undergo mandatory and intensive monitoring of their minds in order to detect the hypothetical onset of a singularity event. It’s even possible that they could be legally forced to undergo psychosurgery in order to prevent it. AGIs visiting such settlements will also undergo such scans (and possibly surgery).

Titanian Commonwealth: AGIs are recognized as full citizens by the Commonwealth and even benefit under Titan’s “one body for every mind” policy. However, new AGIs can expect to undergo extensive monitoring and testing before achieving citizenship. (Optionally, a GM could easily decide that AGI citizens are still subject to heavy surveillance and sousveillance in Titan society.)

Autonomists: AGIs, infomorphs, synthmorphs, Factors, flats… Dude, we’re all sentients, right? Don’t bug them and they probably won’t bug you.

NOTES

Individual habitats, of course, can obviously vary from these generic baselines. (In the case of the PC and LLA, you could even use the listed percentiles to randomly determine a given habitat’s legal framework.) These should be considered tools, not straitjackets.

It should also be noted that the Morningstar Constellation’s attitude towards AGIs is, as far as I can tell, never explicitly spelled out in any of the Eclipse Phase sourcebooks. I’ve intuited the position described above based on specific adventure seeds and historical incidents in Morningstar habitats. Given this paucity of information, however, a GM could easily shift them even further from the Planetary Consortium. (Perhaps you could have them behave like the Conservative Independents I describe above?)

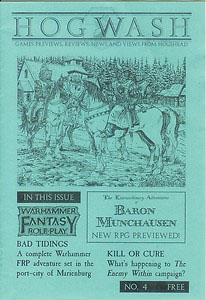

I got subscribed to Hogwash one day while I was perusing

I got subscribed to Hogwash one day while I was perusing