From one point of view, the playing of a roleplaying game can be described as the organized exchange of information between players. Particularly numerical information.

GM: Give me an attack roll.

Player: 17.

GM: You hit.

Player: I do 18 points of damage.

GM: The orc falls dead at your feet!

The player generates a number (rolling their attack skill plus a d20 roll) and gives it to the GM. The GM performs a mathematical operation on that number (comparing it to the orc’s armor class) and the result of that operation causes him to request an additional number from the player. The player generates that number (by rolling the damage for their weapon) and reports it to the GM, who once again does an operation on that number (comparing it to the orc’s remaining hit points) and determines an outcome (the orc dies).

This seems simple and intuitive. And, in this case, it largely is.

But it turns out that how we process and pass numerical information around the table can have a big impact on play. For example:

GM: The orc’s AC is 17. Give me an attack roll.

Player: I hit. 18 points of damage.

GM: The orc falls dead at your feet!

By passing a piece of information (and the associated mathematical operation) over to the player, this GM has significantly improved the efficiency of their communication. If the orc hadn’t died (or if there are other identical orcs), this efficiency compounds over time because the GM doesn’t have to keep passing that piece of information to the player.

Of course, efficiency is not the be-all and end-all of a roleplaying game. There are any number of reasons why a GM might want to keep the orc’s armor class secret from the players (either as a general principle or due to specific circumstances). My point is not that these other considerations are somehow “wrong,” but rather simply that in choosing those other things the GM is sacrificing efficiency.

In many cases, however, the GM isn’t aware that this is a choice that they’re making. And often there are no reasons that might justify the inefficiency; the flow of information (and the impact it’s having on play) just isn’t something the GM is thinking about.

For a long time, this wasn’t something that I understood, either. I’d have discussions with people complaining that such-and-such a system was super complicated and a huge headache to play, and I would be confused because that didn’t match my experience with the game. It would have been easy to pat myself on the back and think, “Well, I guess I’m just smarter than they are,” but I would also have players say to me, “I’d played such-and-such a system before and I hated it, but you really made everything make sense. Can’t wait to play again.” And I’d scratch my head, because I really hadn’t done anything special in terms of teaching how the game worked.

The difference was in the flow of information. Not only can the flow of information around the gaming table be inefficient, it can also be confusing and burdensome.

ECLIPSE PHASE

We think of game mechanics primarily in terms of numerical values and how those values are created or manipulated. But in actual practice, many mechanical  resolutions are performed by multiple people at the table. If you think of the resolution as a ball, it often has to be passed back and forth. Or you might think of it as a dance, and if we — as a table of players — don’t coordinate our actions in performing the resolution we’ll end up stepping on each other’s toes.

resolutions are performed by multiple people at the table. If you think of the resolution as a ball, it often has to be passed back and forth. Or you might think of it as a dance, and if we — as a table of players — don’t coordinate our actions in performing the resolution we’ll end up stepping on each other’s toes.

This efficient passing of information is an example of system mastery. Often, as a table gains experience with a particular RPG together, they’ll intuitively find the patterns of behavior that work. But this doesn’t always happen, and when it doesn’t we can benefit from consciously thinking about:

- What numbers we say

- Who is responsible for saying them

- How we say them

Let me give a simple example of this, using Eclipse Phase.

Eclipse Phase is a percentile system. You modify your skill rating by difficulty and then, if you roll under that number on percentile dice, you succeed. In addition, your margin of success is equal to the number you roll on the dice. If you roll 30+ (and succeed) you get an excellent success; if you roll 60+ you get an exceptional success.

Here’s how things often go when I’m introducing new players to Eclipse Phase (particularly those new to roll-under percentile systems entirely):

GM: Give me a Navigation check.

Player: I got a 47.

GM: What’s your skill?

Player: 50.

GM: Great. That’s a success. An excellent success, actually, because you rolled over 30. Here’s what happens…

The players don’t know what numbers to give me, and so I need to pull those numbers out of them in order to perform the necessary operation (determining if this is a success or failure and the degree of success.) As players start to master the system, this will morph into:

GM: Give me a Navigation check.

Player: I got an excellent success.

GM: Great. Here’s what happens…

They can do this because they’ve learned the mechanics and now know that their roll of 47 when they have a skill of 50 is an excellent success. (In this, the exchange mirrors that of a player attacking an orc in D&D when they know it has AC 17, right? They don’t need to pass me the information to perform the mechanical operation because they can do the operation themselves. In fact, many people like roll-under percentile systems like this specifically because they make this kind of efficiency intuitive and almost automatic.)

But there’s actually a problem with this because, if you recall, Eclipse Phase also features difficulties which modify the target number. This disrupts the simple efficiency and we would often end up with discussions like this:

GM: Give me a Navigation check.

Player: I got an excellent success.

GM: There’s actually a difficulty here. What did you roll?

Player: 47.

GM: And what’s your skill?

Player: 50.

GM: Okay, so you actually failed. Here’s what happens…

This creates all kinds of friction at the table: It’s inefficient. It’s frequently confusing. And either the outcome doesn’t change at all (in which case we’ve deflated the drama of the resolution for no reason) or the player is frustrated that an outcome they thought was going one way is actually going the other.

The reason this is happening is because there is an operation that I, as the GM, need to perform (applying a hidden difficulty) but I’m not being given the number I need to perform that operation. The player has learned to throw the ball to a certain spot (“I got an excellent success”), but I’m frequently not standing at that spot and the ball painfully drops to the ground.

What I eventually figured out is that the information I need from the player is actually “XX out of YY” — where XX is the die roll and YY is their skill rating. I could catch that ball and easily carry it wherever it needed to go.

GM: Give me a Navigation check.

Player: I got 47 out of 55.

GM: An excellent success! Here’s what happens…

And I realized that I could literally just tell players that this is what they needed to say to me. I didn’t need to wait for them to figure it out. Even brand new players could almost instantly groove into the system.

ADVANCED D&D

As you spend more time with a system, you’ll frequently find odd corners which require a different flow of information. In some cases you may be able to tweak  your table norms to account for the special cases, but usually it’ll be more about learning when and how to cue your players that you all need to handle this information differently (and the players gaining the mastery to be able to quickly grok the new, sometimes overlapping, circumstances).

your table norms to account for the special cases, but usually it’ll be more about learning when and how to cue your players that you all need to handle this information differently (and the players gaining the mastery to be able to quickly grok the new, sometimes overlapping, circumstances).

Let’s go back to D&D, for example.

When I’m a DM and I’ve got a horde of orcs attacking a single PC, it’s not unusual for me to roll all of their attacks at once, roll all of the damage from the successful attacks, add all that damage up, and then report it as a single total to the player. It just makes sense to do a running total of the numbers in front of me as I generate them rather than saying a string of numbers to a player and asking them to process the verbal information while doing the running total themselves.

And, of course, it works just fine… right up until a PC gets damage reduction. Now it’s the player who needs to perform a mechanical operation (subtracting their damage reduction from each hit) and doesn’t have the information they need to do that.

Even PCs with multiple attacks usually resolve them one by one for various reasons, so the reverse (players lumping damage together when the GM needs to apply damage reduction) rarely happens. But two of the PCs in my 3rd Edition campaign have weapons that deal bonus elemental damage, and they’ve learned that sometimes I need that damage specifically broken out because creatures are frequently resistant against or immune to fire or electricity damage.

When we first started running into this difficulty, the players defaulted to always giving me the elemental damage separately. But this was an unneeded inefficiency, and we quickly figured out that it was easier for me to simply tell them when they needed to give me the elemental damage separately.

These are simple examples, but they hopefully demonstrate that this sort of mastery is not an all-or-nothing affair. There’s almost always room to learn new tricks.

FENG SHUI

Let’s also take a look at one of these systems that’s fairly straightforward in its mechanical operations, but which can become devilishly difficult if you don’t pass  information back and forth cleanly.

information back and forth cleanly.

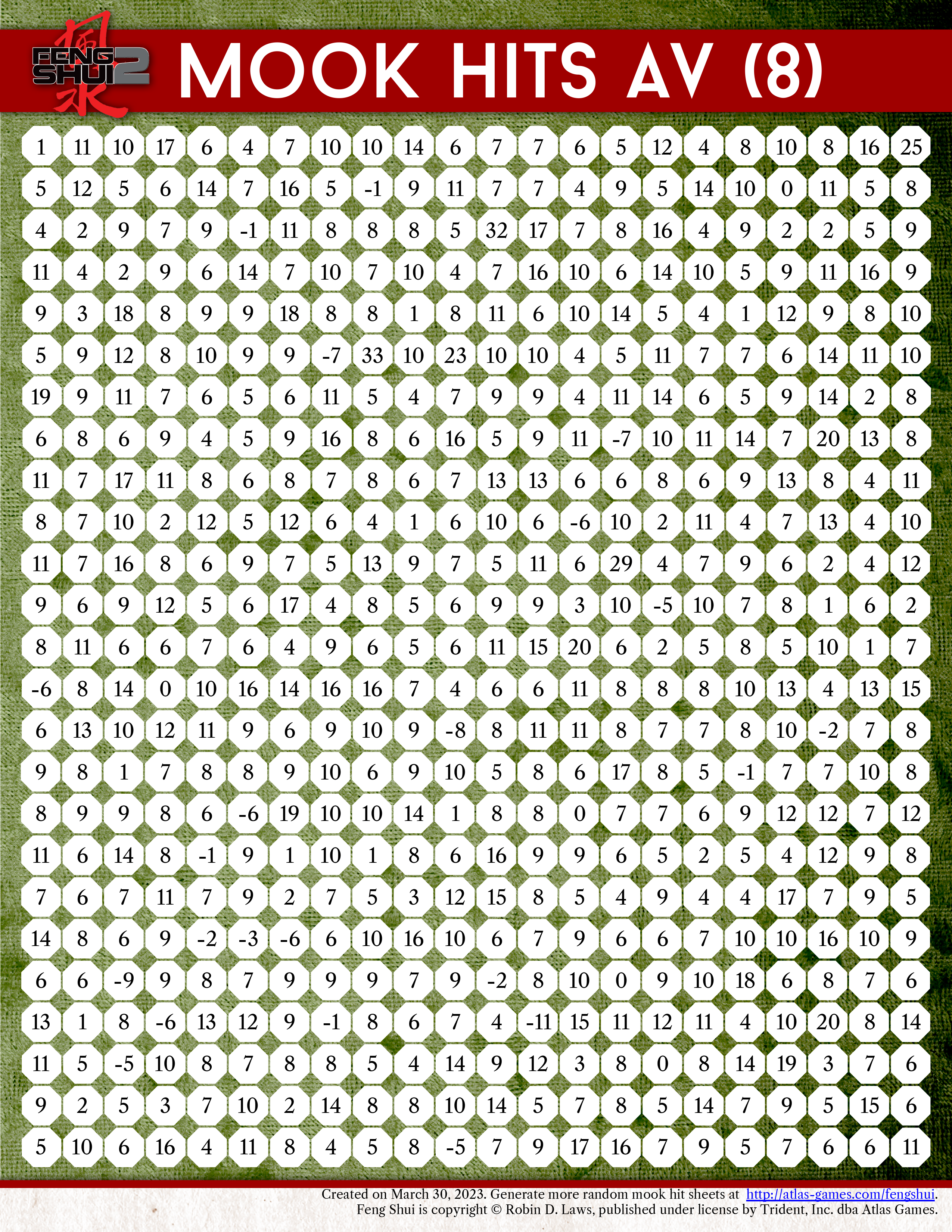

In Feng Shui 2, the dice mechanic produces a “swerve”: You subtract a negative d6 from a positive d6 in order to generate a bell curve result from -5 to +5. (Sixes actually explode and are rolled again, so the curve is smeared out at the ends, but that’s basically how it works.)

When you want to make an attack, you do two things. First, you check to see if you hit:

Roll Swerve + Attack Skill – Target’s Defense

If you hit, you then calculate damage:

Margin of Success + Weapon Damage – Target’s Toughness

Looking at those two equations on the page, there doesn’t seem to be anything particularly exotic about them. In practice, though, I’ve seen players and entire groups get completely tangled up in them. There tend to be two major problems:

- The attacker feels as if they should be able to complete one full step of this process and then report the result… except they can’t, because neither step can actually be completed without information that the defender posseses.

- Upon completing the first step, players want to report a flat success/failure outcome (“I hit”), but if they don’t pass the margin of success to the damage equation they can’t actually calculate damage.

What frequently happens in the latter case is:

GM: The target’s Defense is 17.

Player: (does math) Okay, I hit!

GM: So your damage will be equal to the margin of success plus your weapon damage. What was your margin of success?

Player: Uh… crap. I forgot? Three? Maybe four? Hang on… (does the math again)

Another interesting thing that will happen in this kind of situation is that the players — who don’t like being confused or frustrated! — will try to find ad hoc ways of routing around the problem. In Feng Shui 2, for example, I’ll frequently see players basically say, “Well… I know what this guy’s Defense value is because I attacked him last round. So I’m just going to attack him again to keep it simple.”

The important thing to take away from this is that the players want to solve the problem just as much as you do. But often this kind of ad hoc pseudo-solution just shifts the frustration: They’ve figured out how to make the mechanical resolution flow more smoothly, but they feel trapped by the system into making choices that they don’t necessarily want to make. The insane, over-the-top Hong Kong action of Feng Shui 2, for example, has been compromised as they attack the same guy over and over again.

So let’s say that you find yourself in this situation. How can you fix it?

- Identify the sequence in which mechanical operations must be performed.

- Identify who has the necessary information for each operation.

- Figure out how to pass the information to the necessary person at each stage of the opration.

For example, in Feng Shui 2 who has each piece of information used when resolving an attack?

- Outcome of the swerve roll. (Attacker)

- Attack Skill (Attacker)

- Target’s Defense (Defender)

- Margin of Success (whoever calculated the outcome of the attack roll)

- Weapon Damage (Attacker)

- Target’s Toughness (Defender)

- Wound Points taken (Defender)

If you look back up at the mechanical equations, it should be fairly easy to identify the resolution sequence and the numbers that need to be said:

- Attacker rolls swerve and adds their attack skill. (The game actually calls this the Action Result.) Attacker tells the Defender this number.

- Defender subtracts their Defense from the Action Result. (This is the margin of success. The game calls this the Outcome.) Defender tells the Attacker the Outcome.

- The Attacker adds the Outcome to the Weapon Damage. (The game calls this the Smackdown.) The Attacker tells the Defender the Smackdown.

- The Defender subtracts their Toughness from the Smackdown. (This is the number of Wound Points they take.)

You can see that Robin D. Laws, being a clever chap, identified the significant chunks of information in the system and gave them specific labels (Action Result, Outcome, Smackdown). Other games won’t necessarily do that for you (and even the Feng Shui 2 rulebook, unfortunately, doesn’t specifically call out how the information should be passed back and forth), but you should be able to break down the mechanical processes in any system in a similar manner.

PIGGYBACKING IN GUMSHOE (AND BEYOND!)

Let me close by talking about a mechanical interaction that has multiple players participating simultaneously (which, of course, makes the “dance” of information  more complicated to coordinate).

more complicated to coordinate).

In the GUMSHOE System (used by games like Ashen Stars and Trail of Cthulhu), some group checks are resolved using a piggybacking mechanic:

- One character is designated the Lead.

- The difficulty of the test is equal to the base difficulty + 2 per additional character “piggybacking” on the Lead’s check.

- Those piggybacking can spend 1 skill point to negate the +2 difficulty they’re adding to the check.

The mechanic is very useful when, for example, you want Aragorn to lead the hobbits through the wilderness without being detected by Ringwraiths: The more unskilled hobbits there are, the more difficult it should be for Aragorn to do that, but you still want success to be governed by Aragorn’s skill at leading the group.

Many moons ago I adapted this piggybacking structure to D20 systems like this:

- One character takes the Lead.

- Other characters can “piggyback” on the Lead’s skill check by making their own skill check at a DC equal to half of the DC of the Lead’s check. (So if the Lead is making a DC 30 check, the piggybackers must make a DC 15 check.)

- The lead character can reduce the Piggyback DC by 1 for every -2 penalty they accept on their check.

- The decision to piggyback on the check must be made before the Lead’s check is made.

On paper, this system made sense. When I put it into practice at the table, however, it wasn’t working out. It seemed complicated, finicky, and the players weren’t enjoying using the mechanic.

I gave up on it for a couple of years, and then came back to it and realized that the problem was that I had been sequencing the mechanic incorrectly. One element of this was actually a slight error in mechanical design, but even this was ultimately about the resolution sequence.

The way the mechanic was being resolved originally was:

- The GM declares that, for example, a Stealth check needs to be made.

- The players decide whether they want to use the Piggyback mechanic for this.

- The GM approves it.

- The players choose a Lead.

- The other players decide whether they want to piggyback or not.

- The Lead chooses whether or not they want to lower the Piggybacking DC.

- The Lead would roll their check.

- If the Lead succeeded, the other players would roll their piggybacking checks. (The logic being that if the Lead failed, there was no need for the piggybacking checks. But, in practice, players would see the Lead’s result and then try to opt out of piggybacking if it was bad.)

Here’s what the actual resolution sequence needed to be:

- The GM declares that there is a piggyback check required.

- The players choose their Lead.

- The other players make their piggybacking checks. If any check fails, the largest margin of failure among all piggybacking characters increases the DC of the Lead’s check by +1 per two points of margin of failure.

- The Lead makes their check.

You can immediately see, just from the number of steps involved, how much more streamlined this resolution process is. The only actual mechanical adjustment, however, is to shift the adjustment of the piggybacking DC from a decision made before the piggybacking checks to an effect of those checks.

The take-away here is that while our passing of mechanical information at the table is often numerical, it can also include other elements (like who’s taking Lead in a piggybacking check) which can also be streamlined and formalized for efficiency.