Tagline: Unique. Exciting. Different. Enthralling.

The skies are dim always since the Maker died.

The skies are dim always since the Maker died.

The lights of Puppettown are the brightest beacon in all of Puppetland, and they shine all the time. Once the sun and the moon moved their normal courses through the heavens, but no more. The rise of Punch the Maker-Killer has brought all of nature to a stop, leaving it perpetually winter, perpetually night. Puppets all across Puppetland mourn the loss of the Maker, and curse the name of Punch – but not too loudly, lest the nutcrackers hear and come to call with a sharp rap-rap-rapping at the door.

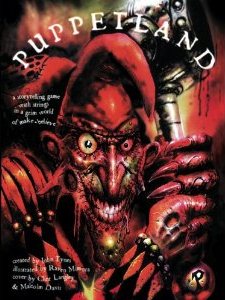

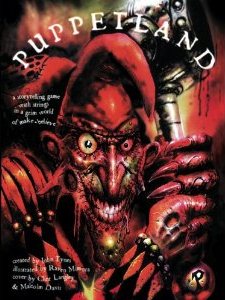

There is no easy way to summarize Puppetland. It is a tour de force in twenty pages by one of the most talented creative forces the roleplaying industry has ever seen. It’s a masterpiece. Unique. Exciting. Different. Enthralling.

Merely reading the book is a powerful experience in its own right – one which is quickly matched only by the act of stepping into Puppetland on your own terms, using the evocatively original mechanics of this revolutionary game.

SETTING

Many years ago, there was a war in the real world. Many people were hurt and terrible things happened. The Maker saw all that was happening, and was sorrowful. His creations were the gentlest of creatures, and they were terribly hurt by these tragedies. The Maker made puppets, and in the face of chaos and violence he made a great creation: Maker’s Land, a place where all his puppets could go and be safe until the war was over.

Maker’s Land was a place of peace and prosperity – where all of the Maker’s puppets could be happy and content. But such perfection could not last. Deep within one of the puppets, Punch, a twisted darkness lived and thrived. One night Punch stole into the Maker’s home, and slew him.

With the Maker’s death, no humans lived in Maker’s Land. But the flesh lived, for Punch took the Maker’s face and made a cruel new face for himself. That wasn’t all he made, either: by morning, he had not just a new face, but six loyal puppet-servants sewn of the Maker’s flesh. These six, whom Punch called his boys, stood beside Punch as he announced to all the land that he was now the king. He was Punch the Maker-Killer, and his word was law.

Punch subjected Maker’s Land to a regime of terror and cruelty which was utterly alien to the innocent and naïve puppets. But where there is life, there is hope.

Across the great lake of milk and cookies lies the small village of Respite. The village is run by Judy, who once loved Punch but does so no more. She knows better than anyone the cruelties he is capable of. She knows the evil that lies in his twisted heart. When Punch killed the Maker, Judy was there and she caught the Maker’s last tear in a thimble of purest silver. With this tear the Maker can be brought back to life, Judy says. This is her fondest dream, and the Maker’s Tear her most cherished possession.

The world of Puppetland is the nightmare of a child, rendered through the lives of puppets who are more than puppets. It is a startlingly powerful vision, rendered in an intense barrage of prose, which instantly captures your heart’s imagination. It is a surgical blade slicing through the detritus of maturity and laying open the veins of your inner child.

SYSTEM

Puppetland is very specifically a game, and should be thought of as such. The object of the game is to defeat Punch the Maker-Killer and save Maker’s Land.

The game of Puppetland functions by way of three basic rules:

The First Rule: An hour is golden, but it is not an hour. Like an actual puppet show, a single session of Puppetland lasts exactly one hour – at the end of which the show comes to an end. When the next show begins, the puppets find themselves back home in bed (or wherever they happen to be staying at the moment). Note that this is very deliberately a measurement of time in the real world. In that hour of real world time, the Puppets may expend days of time within Maker’s Land. (For example, a puppet can say: “I sleep for a week!” and a week has gone by.)

The Second Rule: What you say is what you say. Every word an actor says during a session of Puppetland comes out of his puppet’s mouth (you can avoid this by standing up before speaking, but this should be avoided for if it is overused it will spoil the atmosphere of the game). This rule also reinforces a puppet show style of gameplay: You wouldn’t say, for example, “My puppet moves across the room and opens the door.” Instead, you would say, “I shall cross the room and answer the door!”

The Third Rule: The tale grows in the telling, and is being told to someone not present. This is a reminder of the play-style on which Puppetland subsists. The actors and the Puppetmaster should think of themselves as collaborators in the presentation of a puppet show to an audience which is not present.

CHARACTER CREATION

Character creation begins with the selection between one of the four types of puppets: Finger Puppets, Hand Puppets, Shadow Puppets, and Marionette Puppets. (Additional puppets can, of course, be added at your discretion.) Each puppet type is defined by three characteristics: What they are; what they can; and what they can not. For example:

Finger Puppets are: short and small, light, quick, and weak.

Finger Puppets can: move quickly, dodge things thrown at them even if they only see them coming at the last moment, and move very quietly

Finger Puppets cannot: kick things, throw things, or grab things because they have no legs or arms.

Next you name them. This is done by describing one specific characteristic of the puppet (for example, a puppet with red buttons might be called “Red Buttons”), and then adding to it a common name (for example, Sally Red Buttons or Nadja Purple Hat).

Finally you modify this puppet’s specific characteristics by adding three items to each list.

It should be fairly clear now that actions are adjudicated based on the very simple interaction between the various capabilities and limitations of various puppets: For example, a Finger Puppet can out run a Marionette Puppet (which “move slowly”) every time. That is, after all, the nature of puppets.

One important aspect of character creation which I have glanced over is the drawing of a character portrait. This is done right on the puppet page (character sheet), in the provided picture box which is divided by jigsaw puzzle lines. This picture is actual size — in other words, a player’s puppet can be no larger than the picture box, and you should be able to hold the portraits of two puppets up next to each other and instantly know which is larger than the other.

COMBAT

There is no specific combat system in Puppetland, per se, but there is a specific method of keeping track of “damage” done to a puppet. Basically you do so by filling in the jigsaw puzzle pieces in your puppet’s picture box (this has no relation to the portrait itself – you will use all of the puzzle pieces regardless of whether or not your puppet occupies all of the pieces in the box). You fill in a puzzle piece whenever:

1. The puppet does something it shouldn’t be able to do.

2. Something especially bad happens to the puppet (for example, Punch’s nutcrackers crunch off one of the puppet’s arms).

At the beginning of each new story puppets awake in their bed wholly healed from whatever their prior experiences – but puzzle pieces are never erased. Slowly, over time, the filled-in pieces will accumulate until finally all of the pieces are filled-in. Then the puppet dies (although they do get to live until the end of the current tale, they know their fate).

And that is the full extent of the rules for Puppetland — although some more general guidelines for the Puppetmaster are provided.

CONCLUSION

Bringing this review to a cogent conclusion is no easy task. The game of Puppetland exists on so many levels, with so much power, that I find it difficult to put my thoughts into an order by which they may be expressed.

First and foremost, if there is any doubt left in your mind, let me make it clear that I am all but shoving you out the door and down to your local gaming shop. You simply must buy this game.

In terms of judging Puppetland I can offer nothing except for adulation and congratulations. As I wrote above, the mere reading of the book is an experience well worth the cost of admission all by itself. The combination of poetic prose, rich world design, and potent imagery blows me away every time I come back to it (and I’ve come back to it several times).

Moving beyond the simple act of experiencing the book, I think what most impressed me – after I had given some thought to the matter — is the way in which Tynes effortlessly blends storytelling with gaming. Often when you hear the phrase “storytelling game” what it really means is that the game has been reduced to a set of muddy mechanics that serve “storytelling” by being easily fudged out of existence.

Not so with Puppetland. Here the game creates the story; and the story creates the game. In other words, the mechanics of gameplay are instrumental in the creation of a Puppetland story (note how the three basic rules encourage a very specific type of storytelling experience). On the flip side of the coin, the nature of a Puppetland story (heavily influenced, naturally, by the storytelling mechanics of puppet shows) are the foundation of the game’s mechanics. The symmetry reinforces itself. Brilliant.

Words fail me. Go look for yourself.

SOME MISCELLANEOUS NOTES

The review is done, but I find myself with some housekeeping left undone:

1. There are undoubtedly some of you who don’t understand what you just read. “What the hell is he talking about?” you’re saying. “There are no dice. There aren’t even any numbers! Obviously there are no mechanics!” As I wrote in my review of Baron Munchausen, you folks Just Don’t Get It(TM). Not all games require dice, and the fact that Puppetland succeeds at being a type of game we’ve never seen before does not make it any less a game. But I digress.

2. With Puppetland following on the figurative heels of Baron Munchausen I feel that Hogshead has successfully captured lightning in a bottle twice over – and proven that their New Style line of games is ripe with a potential which most publishers can only dream of. With the forthcoming conceptual sequels to these two games (Whodunnit for Baron Munchausen and Pantheon, a set of five(!) games designed by Robin D. Laws in a single package, for Puppetland), the future looks bright.

3. Puppetland is packaged back-to-back with Tynes’ Power Kill game. Rather than do both games the disservice of attempting to review them together, I am instead going to review them separately. The page count listed for Puppetland is for Puppetland alone; the price is cost of both games together.

4. Puppetland and Power Kill are both available for free from John Tynes’ website, Revland. That being said, I heartily recommend purchasing the book from Hogshead. The artwork of Raven Mimura which accompanies the text is incredibly powerful – and adds much to the experience.

Style: 5

Substance: 5

Author: John Tynes

Company/Publisher: Hogshead Publishing, Ltd.

Cost: $5.95

Page Count: 20

ISBN: 1-57530-601-8

Originally Posted: 1-899749-20-9

I miss John Tynes.

Roleplaying games suffered a great loss when he made the transition to video games over a decade ago.

Puppetland received an incredibly successfuly Kickstarter campaign just a few months ago, however. I’m incredibly excited to see this beautiful game returned to print.

For an explanation of where these reviews came from and why you can no longer find them at RPGNet, click here.

The scene and act divisions in Hamlet pose a troubling scholastic problem.

The scene and act divisions in Hamlet pose a troubling scholastic problem.