Session 15B: The Ghostly Minstrel Plays

In setting up the In the Shadow of the Spire campaign, I was fairly certain that the PCs would choose to settle down in the Ghostly Minstrel: The campaign hook had them awaking there with missing memories, which I felt would create a certain gravitational pull all by itself. I then spiked the situation a bit more by prepaying their rent. (So that going anywhere else would incur additional expense.)

I was basically right. In more than a hundred sessions there have only been two occasions when I think their position at the Ghostly Minstrel was seriously jeopardized: The first relatively early in the campaign when it seemed as if they might all move into Tee’s house. (A different set of rent-free lodgings!) The second later in the campaign when various would-be assassins kept finding them at the Minstrel and they began to conclude that it was no longer safe for them there. (They found a different solution to that problem.)

Tor also had a long-standing fascination with the idea of buying a house, which is only poorly reflected in the campaign journal (as it usually only came up tangentially during other conversations). He never seemed able to convince anyone else of the virtues of real estate investment, however.

Knowing that the PCs would be staying at the Ghostly Minstrel, I wanted to make sure to bring that building to life for them. To make it feel like a real place. To make it feel like home.

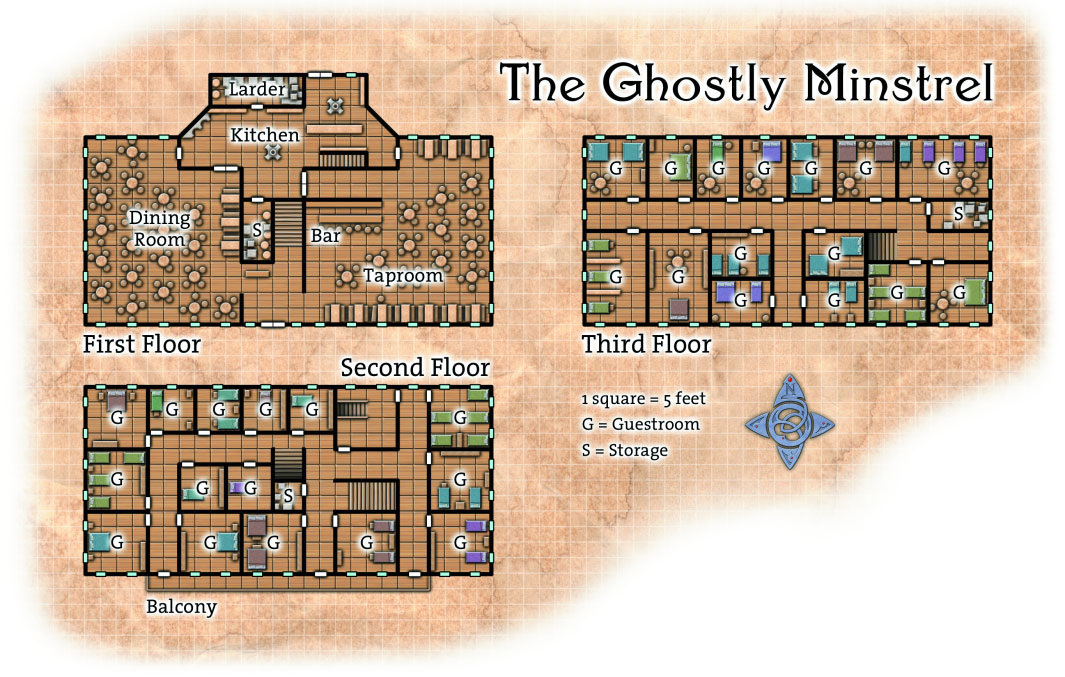

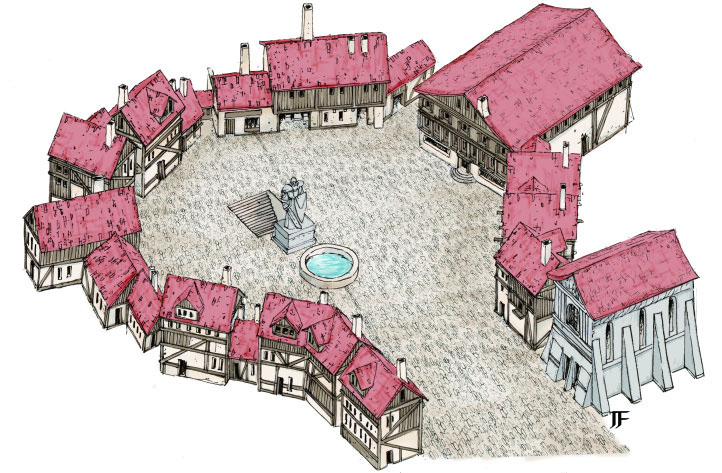

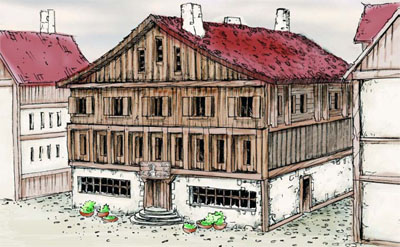

I’ve previously discussed the graphical advantages of using Cook’s elaborately detailed setting. This included not only multiple pictures of the Ghostly Minstrel, but also complete floorplans of the entire building. But what would really breathe life into the Ghostly Minstrel would be its patrons.

I knew that establishing would be a long-term project. Dumping them on the PCs all at once wouldn’t create meaningful relationships; it would just be informational overload. These NPCs needed to become familiar faces.

BUILDING A CAST OF CHARACTERS

The first step was to actually establish who the characters at the Ghostly Minstrel were. Here, too, Monte Cook had done the initial work for me, astutely including a list of “regulars” at the tavern: Sheva Callister, Daersidian Ringsire, Jevicca Nor, Rastor, Steron Vsool, Urlenius the Star of Navashtrom, Araki Chipestiro, Mand Scheben, and the Runewardens.

Some of these characters resonated with me. Others did not. I culled the list and then supplemented it with other characters that I knew would likely feature later in the campaign. Then I did a little legwork to pull details on these characters together onto a single cheat sheet for easy reference during play.

USING THE CAST

At this point what you have is something that’s not terribly dissimilar from the Party Planning game structure I’ve discussed in the past. The primary difference is that rather than being crammed into a single big event, the interactions in the Ghostly Minstrel’s common room were decompressed over the course of days and weeks. Using the Party Planning terminology:

- Who’s in the common room each night?

- What’s the Main Event Sequence for tavern time?

- What are the Topics of Conversation?

For the first few days of the campaign, I took the time to hand-craft these elements. This allowed me to think about the pacing and sequence for introducing different NPCs. (Would it be more interesting for them to meet Jevicca and have her mention Sheva? Vice versa? Meet them both at the same time?)

Eventually, the campaign moved beyond that phase. At that point, an evening at the Ghostly Minstrel would consist of:

- Looking at my cheat sheet and randomly selecting a mix of characters to be present.

- Looking at my campaign status sheet to see what the current news on the street was and assuming that those would likely be the current Topics of Conversation.

- Occasionally interject a specific, pre-planned development – either in terms of character relationships or scenario hooks.

REINCORPORATION

The final step was to reincorporate the Ghostly Minstrel NPCs into other facets of the campaign (and vice versa). You can see that, for example, with the Harvesttime celebration at Castle Shard, where Sheva and Urlenius both showed up. Conversely, although he also appeared on Cook’s list of regulars at the Ghostly Minstrel, I introduced Mand Scheben first as someone looking to hire the PCs and then had them notice him hanging out in the common room.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Lately I’ve gotten a little lazier when it comes to the cast of characters at the Ghostly Minstrel. Other parts of the campaign have gotten quite complicated, and there are a lot of balls being kept in the air without also juggling in tavern time. The PCs themselves are also less focused on the Minstrel, and their penchant for simply teleporting directly into and out of their rooms also bypasses the traditional “you see so-and-so and so-and-so chatting in the common room” framing that often marked the end of a long adventuring day during these early sessions.

Fortunately, if you put in the early work on this sort of thing, it builds a foundation that you can comfortably coast on for a long a time. For the players, the Ghostly Minstrel is a real place that they have a personal history with, even if it’s been awhile since it’s had a spotlight shone on it. And it only takes a few light reminders – and a few familiar faces – for the Ghostly Minstrel to surge back to life for them.

Fortunately, if you put in the early work on this sort of thing, it builds a foundation that you can comfortably coast on for a long a time. For the players, the Ghostly Minstrel is a real place that they have a personal history with, even if it’s been awhile since it’s had a spotlight shone on it. And it only takes a few light reminders – and a few familiar faces – for the Ghostly Minstrel to surge back to life for them.

Recently, however, we’ve had a new player join group and this, for lack of a better term, complacency has become problematic: The simple references which resonate with the other players simply have no resonance for him.

(At the most basic level, think of it like this: When I say, “You walk into the Ghostly Minstrel,” to the long-established players, a vivid and fully-detailed image is conjured up in their mind’s eye. That’s all it takes because we’ve all collectively done the work, right? That doesn’t happen for the new player, though, because it’s not a place that already lives in his imagination. The same thing applies, but even moreso, for the relationships with the NPCs.)

As such, I want to kind of beef up the group’s engagement with the Ghostly Minstrel again for at least a little awhile. It was probably time to do so any way, because a lot of these relationships had just been kind of floating along in a gentle haze for a long time now.

Because I do have so many other aspects of the campaign I’m juggling, however, I’ve decided to approach this through a slightly more formal structure. (The structure allows me to offload at least some of the mental load, right? It frees up more of my brain to focus on other things during actual play.) So what I’ve developed is:

- A random guest list for determining who’s in the common room on any given night that the PCs stop in. (Roll on it 1d6 times.)

- Stocking each guest with a short sequence of conversational gambits or interpersonal developments.

My expectation is that I should be able to very quickly reference this page in my campaign status sheet and rapidly generate a 5-10 minute roleplaying interaction any time the PCs choose to engage with the common room.

EXAMPLE OF PLAY

So this is the random table I set up:

| Sheva Callister | |

| Parnell Alster | |

| Daersidian Ringsire & Brusselt Airmol | |

| Jevicca Nor | |

| Rastor | |

| Steron Vsool | |

| Urlenius | |

| Mand Scheben | |

| Cardalian | |

| Serai Lorenci (Runewarden) | |

| Shurrin Delano (Runewarden) | |

| Sister Mara (Runewarden) | |

| Canabulum (Runewarden) | |

| Aliya Al-Mari (Runewarden) | |

| Zophas Adhar (Runewarden) | |

| Talia Hunter | |

| Tarin Ursalatao (Minstrel) | |

| Nuella Farreach | |

| Iltumar | |

| The Ghostly Minstrel |

I roll 1d6 and get a result of 4. Using d20 rolls, I note that Aliya Al-Mari, Serai Lorenci, Shurrin Delano, and Urlenius are in the room. (There’s probably also other people, but these are the notable characters, several of whom the PCs have previously been introduced to.)

Next I look at the short list of topics I had prepped for these characters. I actually prepped the adventuring party known as the Runewardens as a group, so this particular slate of results simplifies things somewhat:

RUNEWARDENS

- Serai Lorenci has joined the Inverted Pyramid. Drinks all around!

- Canabulum is challenging people to arm wrestling.

- Aliya Al-Mari storms out of the common room. She’s angry because Serai has told her he’s in contact with Ribok again.

URLENIUS

- Interested in the rhodintor. (Heard about their presence in the White House from City Watchmen.) He has had visions foretelling that they both were and will become a great threat to Ptolus.

- He spoke with Dominic recently. Matters weigh heavily with him, but he is trusting to Vehthyl.

- Tells a rambunctious story about how he, Soren Clanstone, and six soldiers of Kaled Del once transformed a cavern into a fortress and withstood the siege of two dozen dark elves. Then demands a PC tell a story.

Some of these notes may only make sense with the full context of the campaign and/or the Ptolus sourcebook behind them, but hopefully the general thrust here is clear. (Ribok, for example, is a chaositech expert who made introductions between Serai and the Surgeon in the Shadows. Serai almost got himself in quite a bit of trouble when the Surgeon attempted to modify his body, and the other Runewardens barely bailed him out. So Aliya isn’t happy he seems to be dabbling with this dangerous technomancy once again.)

When in doubt, I’m going to default to the first bullet point. And given the preponderance of Runewardens my dice have generated, a celebration of Lorenci’s acceptance by the Inverted Pyramid makes sense. (I also decide that the other Runewardens will show up later in the evening if the PCs engage here.)

Urlenius might be doing his own thing, but he knows members of the Runewardens, so let’s go ahead and just have him drinking with them. The PCs know him better than the members of the Runewardens present, so he can also invite them over. The Runewardens can chat about their news, then Urlenius will ask the PCs about the rhodintor. Might prompt the Runewardens to mention their own run-ins with rhodintor or rhodintor lore. (I’ll check my rhodintor notes for that.)

I’ll mark these items as used on my campaign status sheet, and as part of my prep for the next session I’ll replace the bullet points I’ve used with new points.