When I joined Atlas Games as the RPG Producer in December 2018, I inherited four of the best roleplaying games ever published: Feng Shui, Over the Edge, Ars Magica, and Unknown Armies. I knew that to do these games proper justice in the future, the first thing I needed to do was fully grasp their past. These were all games which I had played before (although, ironically, none of them in their current edition), but there was still a lot for me to learn. From day one, therefore, I embarked on a year-long project to not only bring every one of these games to my gaming table, but to also read every single supplement ever published for them.

When I joined Atlas Games as the RPG Producer in December 2018, I inherited four of the best roleplaying games ever published: Feng Shui, Over the Edge, Ars Magica, and Unknown Armies. I knew that to do these games proper justice in the future, the first thing I needed to do was fully grasp their past. These were all games which I had played before (although, ironically, none of them in their current edition), but there was still a lot for me to learn. From day one, therefore, I embarked on a year-long project to not only bring every one of these games to my gaming table, but to also read every single supplement ever published for them.

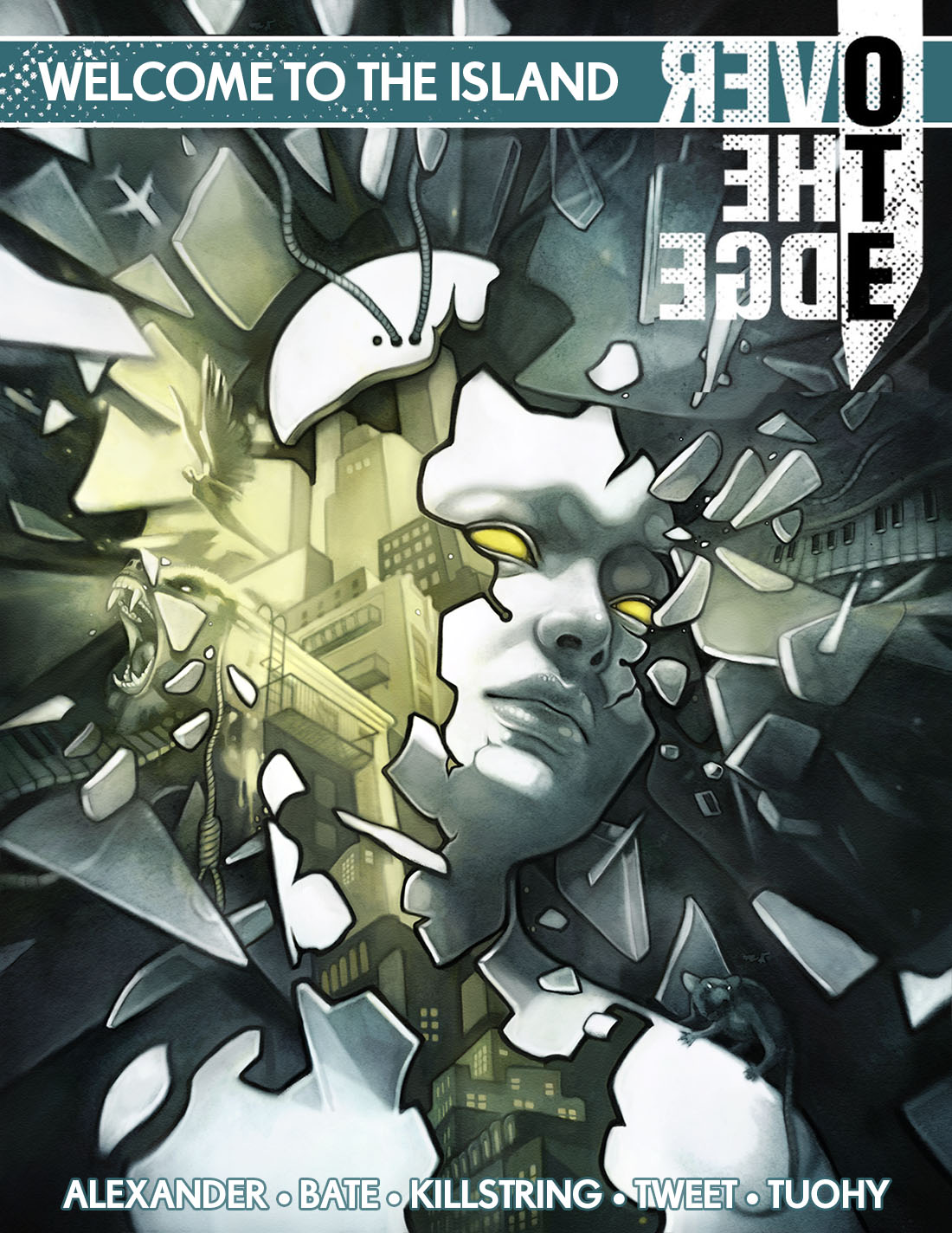

As I worked my way through the corpus of Over the Edge supplements at the beginning of the year, I reflected on how difficult it is to produce scenario support for this type of RPG. Over the Edge is one of those games which presents an incredibly awesome setting filled to the brim with all kinds of amazing things for players and GMs to explore, but which — for precisely that reason! — doesn’t have a specific scenario structure that’s universally shared by its players. Without that universal scenario structure, it becomes very difficult to create published scenarios that can be reliably used by individual GMs.

(Which is not to say that Over the Edge hasn’t had some truly great scenarios written for it over the years. My personal favorites include Robin D. Laws Unauthorized Broadcast, Stephan Michael Sechi’s Welcome to Sylvan Pines, Jeff Tidball’s “In the SACQ”, Chris Pramas’ “The Jackboot Stomp,” and Greg Stolze’s “The Furchtegott File.” But although I love all of those scenarios, it would be virtually impossible for me to fit them all into the same campaign. Which is kind of my point.)

By contrast, for example, it’s very easy to create plug ‘n play scenarios for Shadowrun: Because every group is assumed to be shadowrunners who get jobs from a Mr. Johnson, all you need to do is frame your scenario as a job being offered by a Mr. Johnson and it can probably be used in 99% of Shadowrun campaigns.

One solution, of course, would be to simply eschew producing published scenarios for the game. There are any number of similar games which have done the same, focusing their product lines on cool setting supplements that give GMs even more awesome options for their campaigns. This , however, would be in significant conflict with my belief that roleplaying games flourish only in the presence of strong scenario support:

- Published scenarios are the single best way for GMs to grok how the game is supposed to work.

- Ready-to-play scenarios are the best way to convince GMs to try running the game for the first time.

- Incredibly cool scenarios are a great way to get people excited about running the game. (There’s any number of scenarios I’ve personally run because I just needed to see what would happen at the table; or that were so amazingly cool that I just had to share them with my players.)

- There are a lot of would-be GMs who, frankly, need the scenario support: Their time is limited and without published adventure material they won’t be able to run the game.

There’s also the fact the fact that I think published scenarios often improve campaigns in their own right, resulting in cool stuff that wouldn’t be possible otherwise.

Nonetheless, I knew that if I produced a typical scenario anthology for Over the Edge, a high percentage of the scenarios — no matter how good they were! — wouldn’t be usable by any given GM simply because they weren’t sympatico with their campaign. That would make the book substantially less valuable to everybody. I needed to fix that problem.

So I reached out to existing Over the Edge GMs to talk about the campaigns they had run and the campaigns they were looking forward to running with the new edition of the game.

What I slowly came to realize was that there were, in fact, several broad categories that most Over the Edge campaigns fell into. The specifics were different enough to create a crazy kaleidoscope of endless possibility, but the categories were tight enough that a GM operating within a given category would generally be able to adapt scenario hooks aimed at that category. So for the upcoming Welcome to the Island adventure anthology, I instructed my writers to include hooks for the following categories:

- Agents: Why would someone hire the PCs to get involved in this scenario? (Or, alternatively, why do the PCs need to do this on behalf of their patron without explicit orders?)

- Burger: How would someone who literally just got off the plane and caught a taxi from the Terminal get involved in this?

- Cloaks: Why would the various conspiracies on the Island care about this scenario (and send their trusty agents, the PCs, to deal with it)? Or, alternatively, what opportunity do the PCs become aware of and how do they become aware of it?

- Gangs: How do street-level operatives get tangled up in the scenario?

- Mystics: If the PCs are focused on mystic shit, how does that angle them into the scenario? Does someone/something seek them out due to their mystic powers? Do their mystic powers trigger or respond strongly to the situation? Does ancient arcane lore or a prophecy point them at the scenario?

It was also necessary to keep the hooks tight: Scenario hook sections in published adventures have a tendency to bloat up and claim more of the scenario’s word count than their utility warrants. This would be particularly true if people started writing up elaborate, multi-scene hooks for five different options. All we really needed was one or, at most, two paragraphs for each hook. (In no small part because, in my experience, GMs are going to heavily customize the hook to the specifics of their own campaign in any case.)

This actually lead to some initial confusion as we put this into practice. There was more than one person who produced a draft featuring stuff like, “Here’s stuff that Agents might find potentially interesting about what’s going on.” But I pushed: Brevity doesn’t equate to generality. A scenario hook needs to be specific. What is the specific thing that gets the PCs involved in the current situation?

HOOKS AT THE END

In the future, I will recommend that writers actually write their scenario hooks last. (Or possibly second-to-last depending on how you look at it.)

It probably won’t come as a surprise to most people reading this, but I want scenarios that are situations, not plots. You don’t necessarily need a specific hook in order to design a really cool, interactive situation filled to the brim with exciting stuff for the PCs to explore and for the GM to actively play. Requiring five different scenario hooks for each scenario actually emphasized this: Since the scenarios could not be dependent on any one on of these hooks, the scenarios quickly became independent of all of them, making it much easier for a GM who didn’t find any of those specific hooks interesting to nevertheless find a multitude of ways to draw their PCs into the situation.

At the same time, the fact that the scenario still needed to hypothetically support any one of those hooks also resulted in a richer scenario no matter which hook you used. The requirement necessarily forced the designers to create situations that were more dynamic, complex, and interconnected than they might have otherwise.

This is where this advice is potentially useful for homebrewers, too: If, for example, you use the Three Clue Rule to offer several options by which the PCs might become engaged with a given scenario, you will find that the need to include those three clues will inherently cause you to design more depth into the scenario. And that depth, in turn, will make it easier to improvise ways for the PCs to become engaged even if the three methods you’ve prepped don’t work for some reason.

For similar reasons, I suspect that even GMs who don’t have campaigns fitting one of the five broad categories I identified will nevertheless find it much easier to incorporate the scenarios in Welcome to the Island into their odd-ball campaigns. Having three to five different hooks makes it more likely that one of them can be trivially adapted to unusual circumstances. Or might feature a GMC similar enough to someone close to the PCs that you can make the whole thing intensely personal instead.

The Alexandrian has received a 2019 ENnie Nomination for Best Online Content.

The Alexandrian has received a 2019 ENnie Nomination for Best Online Content.

When I joined Atlas Games as the RPG Producer in December 2018, I inherited four of the best roleplaying games ever published:

When I joined Atlas Games as the RPG Producer in December 2018, I inherited four of the best roleplaying games ever published: