Go to Part 1

This will probably be the most controversial entry I write for the GM Don’t List, because there are a lot of players who absolutely LOVE this. And if the players love it, why wouldn’t you do it?

Well, try to bear with me because we’ll get to that.

The technique we’re talking about is description-on-demand: The GM directs an authorial question at a player, giving them narrative control to define, describe, or determine something beyond the immediate control of their character. Examples include stuff like:

- What is Lord Fauntleroy’s deepest secret?

- You open the door and see Madame DuFerber’s bedroom. What does it look like?

- Okay, so you pull him off to one side, confess your love to him, and demand to know if he feels the same way. What does he say?

- What does Rebecca [your PC] know about the Dachshund Gang? Who’s their leader?

- Robert, tell me what the name of the mountain is.

- Okay, you find some juicy blackmail on Mayor McDonald. What is it that he’s done? What evidence do you find?

If you haven’t encountered this technique before, the key thing to understand is that none of the characters being defined here are PCs: The GM isn’t asking Lord Fauntleroy’s player what their character’s deepest secret is. They’re asking the players to step out of their character and create an element of the game world external to their character (often in direct response to their character taking interest in that element of the game world).

It’s description-on-demand because the GM is demanding that a player provide description.

MANY PLAYERS DON’T LIKE IT…

Description-on-demand tends to be a fad that periodically cycles through the RPG meme-sphere. When it does so, the general perception seems to be that every player thinks this is the greatest thing since chocolate-dipped donuts.

So let’s start there: This is not true. Many players do love it. But many players DO NOT. In fact, a lot of players hate it. There are a significant number of players for whom this is antithetical to the entire reason they want to play an RPG and it will literally ruin the game for them.

I’m one of those players. I’ve quit games because of it and have zero regrets for having done so.

So, at a bare minimum, at least take this lesson away with you: Check with your players before using description-on-demand. Because it can absolutely be a poison pill which will ruin your game for them.

Okay… but why do they hate it?

A brief digression: If you’re not familiar with the distinction between roleplaying games and storytelling games, I recommend checking out Roleplaying Games vs. Storytelling Games. The short version is that roleplaying games feature associated mechanics (where the mechanical choices in the game are directly associated to the choices made by your character, and therefore the act of making mechanical choices in the game – i.e., the act of playing the game – is inherently an act of roleplaying) and storytelling games feature narrative control mechanics (where the mechanics of the game are either about determining who controls a particular chunk of the narrative or about determining the outcome of a particular narrative chunk).

When I’m playing a roleplaying game (as opposed to a storytelling game), I am primarily interested in experiencing the game world from the perspective of my character: I want to experience what they experience, make the decisions that they would make, and vicariously experience their fictional life. The reason I want this experience can be quite varied. Roleplaying can be enjoyable in a lot of different ways (catharsis, escapism, experimentation, sense of wonder, joy of exploration, problem-solving, etc.) and the particular mix for any particular game or moment within a game can vary considerably.

Description-on-demand, however, literally says, “Stop doing that and do this completely different thing instead.”

This is not only distracting and disruptive, it is quite often destructive. There are several reasons for this, but the most significant and easy to explain is that it inverts and negates the process of discovery. You can’t discover something as your character does if you were the one to authorially create it in the first place. This makes the technique particularly egregious in scenarios focused on exploration or mystery (which are at least 90% of all RPG scenarios!) where discovery is the central driving force.

Not all players who dislike description-on-demand hate it as much as I do. Some will be merely bored, annoyed, or frustrated. Others will become stressed, anxious, or confused when being put on the spot. Some will just find their enjoyment of the game lessened and not really be able to put their finger on why. But obviously none of those are good outcomes and you need to be aware that they’re a very real possibility for some or all of the players at your table before leaping into description-on-demand.

…BUT SOME PLAYERS DO

So why do some players love this technique?

And they clearly DO love it. Some enjoy it so much that they’ll just seize this narrative control for themselves without being prompted by the GM. (Which can cause its own problems with mismatched expectations, but that’s probably a discussion for another time.)

So… why?

If we keep our focus on the tension between discovery and creation, it’s fairly easy to see that these are players who don’t value discovery as much. Or, at least, for whom the joys of creation outweigh the joys of discovery.

I’m one of those players. When I’m playing a storytelling game, I love being offered (or taking) narrative control and helping to directly and collectively shape the narrative of the world.

…

… wait a minute.

How can both of these things be true? How can I both hate it and love it?

Well, notice that I shifted from talking about roleplaying games to talking about storytelling games.

Here we get to the crux of why description-on-demand is a poor GMing technique. Because while there are times I prefer to be focused on in-character discovery, there are ALSO times when I’m gung-ho for authorial creation. And when that happens, description-on-demand in a traditional RPG is still terrible.

Remember that this technique gives us the opportunity to experience the joy of creation, but does so only by destroying the joy of discovery. There is an inherent trade-off. But when it comes to description-on-demand, the trade-off sucks. I’m giving up the joy of discovery, but in return I’m not getting true narrative control: Instead, the GM arbitrarily deigns to occasionally ask my input on very specific topics (which may or may not even be something that I care about or feel creatively inspired by in the slightest).

Description-on-demand techniques in an RPG dissociate me from my character while offering only the illusion of control.

In an actual storytelling game, on the other hand, I have true narrative control. The structure and mechanics of the game let me decide (or have significant influence over) when and what I want narrative control over. This is meaningful because I, as a player, know which moments are most important to my joy of discovery and which ones aren’t. (This is often not even a conscious choice; the decision of when to take control and when to lean back is often an entirely subconscious ebb-and-flow.)

Note: This discussion is largely assuming storytelling games in which players strongly identify with a specific character (“their” character, which they usually create). There are many other storytelling games – like Once Upon a Time or Microscope – in which this is not the case. In my experience many of those games still feature a tension between discovery and creation, but the dynamics are very different in the absence of a viewpoint character.

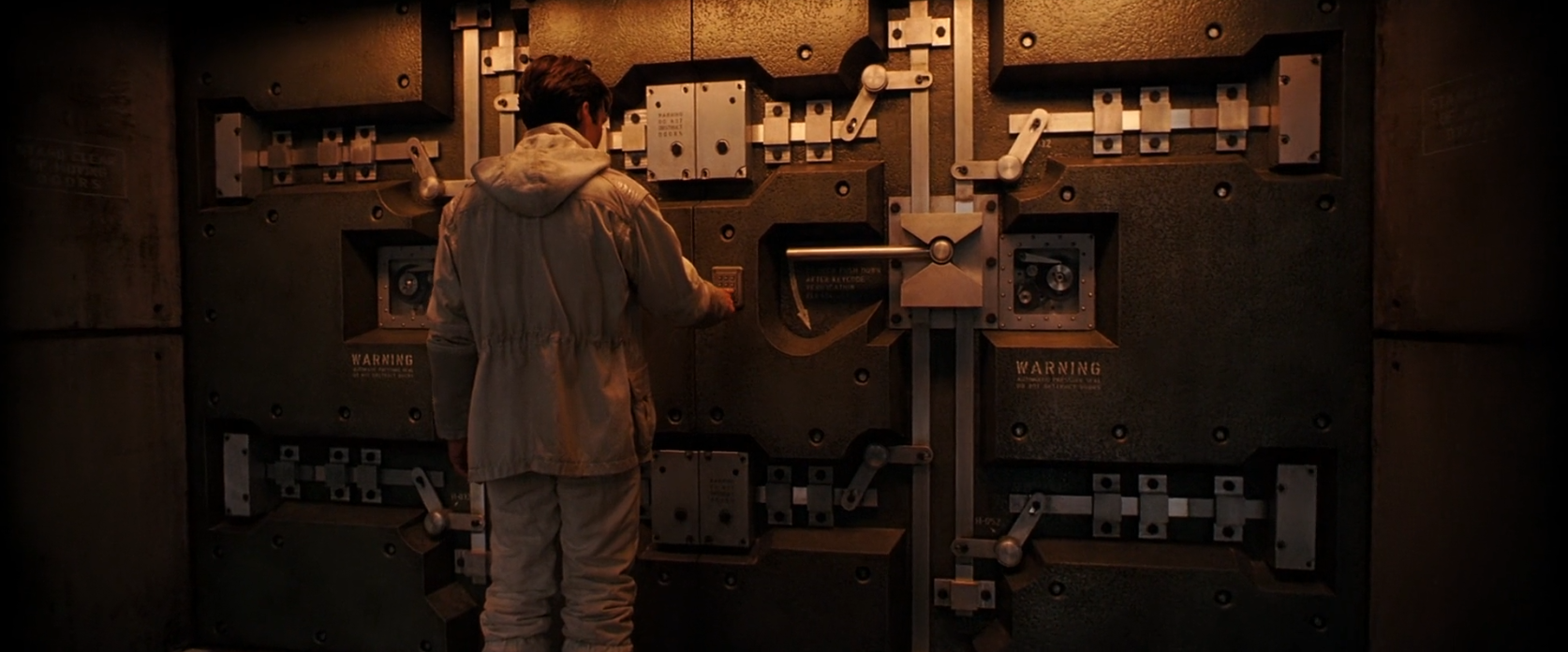

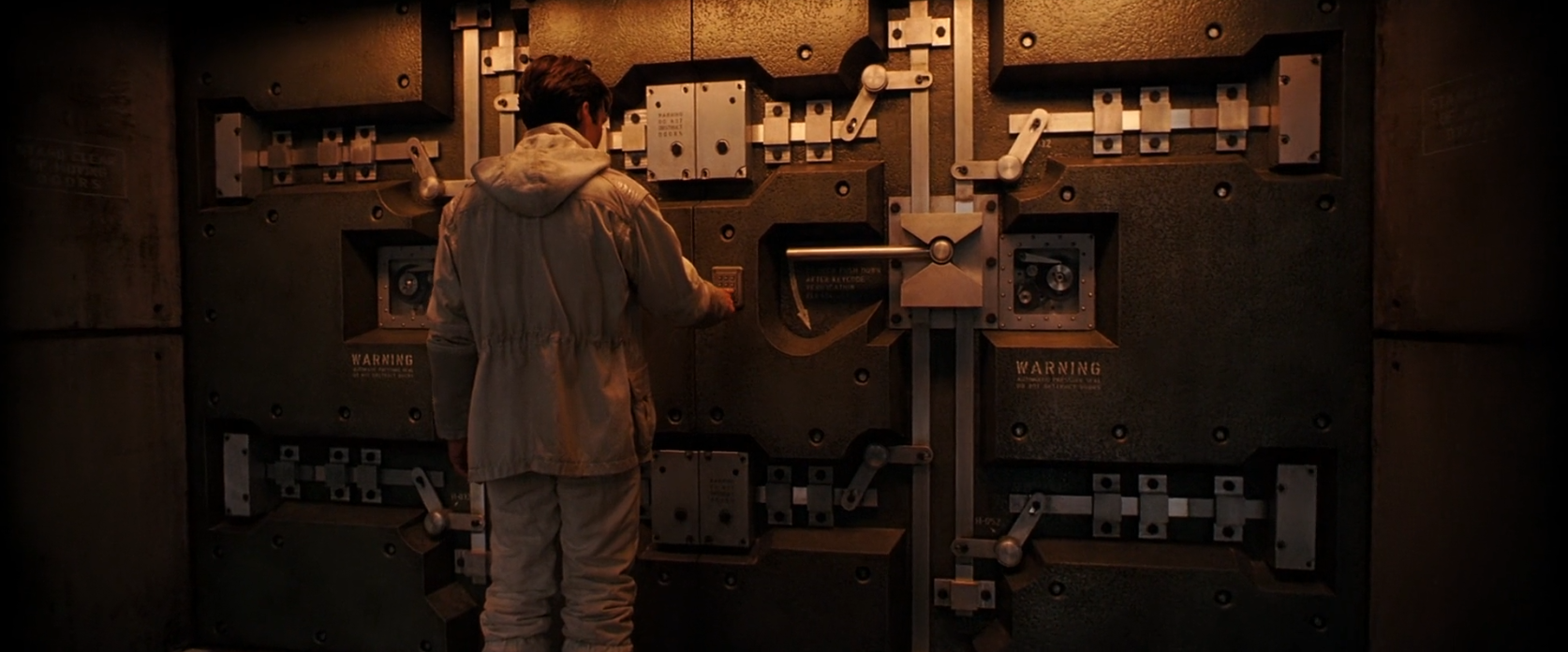

Towards the end of the movie Inception, Eames looks towards the dream vault they’ve been trying to break into for basically the entire movie and says, “It’s a shame. I really wanted to know what was going to happen in there. I swear we had this one.”

Now, imagine the vault door opening. And the GM says: “Okay, Eames, tell me what you see in there!”

For one player, this is great! The importance of this vault has been relentlessly established. The entire narrative has been pushing towards this revelation and now THEY have the opportunity to create what’s inside it!

For another player, this is a disastrous, gut-wrenching disappointment. They’ve spent all this time anticipating this moment; speculating about what the vault might contain, imagining different possibilities, parsing together clues to try to figure it out. And now they’re going to find out! And, instead, the GM announces that there was never any solution to this riddle. There was no plan. No mystery to be solved. Just an empty madlibs puzzle waiting to be filled. “I really want to find out what’s in that vault,” but instead, “Nope, you don’t get what you want. In fact, you have to actively participate in disillusioning yourself.”

For a third player, they don’t really care about having narrative control, but they don’t really have any strong ideas about what should be in the vault and aren’t interested in making a creative decision about that.

And here’s the key thing: You have absolutely no way of knowing which player is which.

In fact, the answer can very easily change from one moment to the next. One player may want an in-character pay-off for the mystery of the vault, but has strong opinions on what Lord Fauntleroy’s deepest secret is and would love to define that. But another may well feel the exact opposite, while a third has no interest in either, and a fourth will be disappointed by any player defining what’s in the vault, because it’ll reveal there wasn’t a canonically true answer.

(And, yes, I have very deliberately chosen a narrative in which the characters do, in fact, have influence — albeit an indirect one — over what the vault will contain. I want you to challenge your preconceptions within the uncertainties of this liminal space. While you’re here, if you’re familiar with the movie, ask yourself whether your opinion on this interaction would be different if the GM was asking Robert Fischer’s player what was inside the vault instead of Eames’ player. Do you see how a different player of Robert Fischer might want the exact opposite answer?)

The cool thing about most narrative control mechanics is that they give you the ability to say, “This is what I care about. This is what I want to create.” And, conversely, “This is not something I care about. This is, in fact, something I DON’T want to be responsible for creating.”

CONCLUSION

Here’s my hot take.

I think description-on-demand is primarily — possibly not exclusively, but primarily – popular with players who have never played an actual storytelling game or who would desperately prefer to be playing one.

Because the thing that description-on-demand does — that little taste of narrative control that many players find incredibly exciting — is, in fact, an incredibly shitty implementation of the idea.

If you’re interested in an RPG, this is like playing Catan and having the host demand that you roleplay scenes explaining your moves in the game. (Just play an actual RPG!)

On the other hand, if you’re craving an STG, then description-on-demand in a traditional RPG is like playing co-op with an alpha quarterback who plays the entire game for you, but then occasionally says, “Justin, why don’t you choose the exact route your meeple takes to Sao Paolo?” and then pats themselves on the back for letting you “play the game.”

(This applies even if you’re playing an RPG and are just interested in adding a little taste of narrative control to it: You would be better off grafting some kind of minimal narrative control mechanic onto the game so that players can, in fact, be in control of their narrative control.)

To sum up, the reason description-on-demand makes the GM Don’t List is because:

- If that’s not what a player wants, it’s absolutely terrible.

- If it is what a player wants, it’s a terrible way of achieving it.

BUT WAIT A MINUTE…

There are several other techniques which are superficially similar to description-on-demand, but (usually) don’t have the same problems. Let’s briefly consider these.

FENG SHUI-STYLE DESCRIPTION OF SETTING. Robin D. Laws’ Feng Shui was a groundbreaking game in several ways. One of these was by encouraging players to assert narrative control over the scenery in fight scenes: If you want to grab a ladder and use it as a shield, you don’t need to ask the GM if there’s a ladder. You can just grab it and go!

Notably this is not on-demand. Instead, the group (via the game in this case) establishes a zone of unilateral narrative control before play begins. It is up to the players (not the GM) when, if, and how they choose to exercise that control. Players are not stressed by being put on the spot, nor are they forced to exert narrative control that would be antithetical to their enjoyment.

EXTENDED CHARACTER CREATION: This is when the GM asks a question like, “What’s Rebecca’s father’s name?” Although it’s happening in the middle of the session, these questions usually interrogate stuff that could have been defined in character creation.

This generally rests on the often unspoken assumption that the player has a zone of narrative control around their character’s background. Although this narrative control is most commonly exercised before play begins, it’s not unusual for it to persist into play. (Conversely, it’s similarly not unusual for players to improvise details from their character’s background.) This can even be mechanically formalized. In Trail of Cthulhu, for example, players are encouraged to put points into Languages without immediately deciding which languages they speak. (Each point can then be spent during play to simply declare, “I speak French,” or the like.)

Because it’s unspoken, however, both the authority and boundaries of this zone can be ill-defined and expectations can be mismatched. (The problems that can result from this are probably yet another discussion for another time.)

There’s also a gray zone here which can easily cross over into description-on-demand. “What’s your father’s name?”, “Describe the village where you grew up,” and “You grew up in the same neighborhood as the Dachshund Gang, so tell me who their leader is,” are qualitatively different, but there’s not necessarily a hard-and-fast line to be drawn.

RESOLUTION OF PLAYER-INITIATED ACTION: So if saying, “You find some juicy blackmail on Mayor McDonald. What is it that you’ve caught him doing?” is description on demand, then what about when the GM says, “You deal 45 hit points of damage. He’s dead. Describe the death blow,” that must also be description-on-demand, right? I mean, the GM even said the word “describe!”

There is some commonality. Most notably, you’re still putting players on the spot and demanding specific creativity, which can stress some players out in ways they won’t enjoy. But this effect is generally not as severe, because the player has already announced their intention (“hit that guy with my sword”) and they probably already have some visualization of what successfully completing that intention looks like.

In terms of narrative control, however, there is a sharp distinction: You are not asking the player to provide a character-unknown outcome. You are not dissociating them from their character.

This is true in the example of the sword blow, but may be clearer in a less bang-bang example. Consider Mayor McDonald and the difference between these two questions:

- “You find some juicy blackmail on Mayor McDonald. What is it that you’ve caught him doing?”

- “You find some juicy blackmail on Mayor McDonald. He’s been cheating on his wife with a woman named Tracy Stanford who works in his office. How did Rebecca find this out?”

In the first example, the GM is asking the player to define an element of the game world outside of their character and their character’s actions. In the second example, the GM has defined that and is instead asking them to describe what their character did. Although it’s become cognitively non-linear (the player knows the outcome, but is describing actions their character took before they knew the outcome), it is not dissociated from the character.

The same is true of the sword blow: The mechanics say the bad guy dies; take a step back and roleplay through how that happened.

(For a longer discussion of closely related stuff, check out Rulings in Practice: Social Skills.)

WORLD DEVELOPMENT BETWEEN SESSIONS: As a form of bluebooking, players may flesh out elements of the campaign world between sessions.

Sometimes this is just a more involved version of extended character creation. (“Pete, it looks like that Order of Knighthood your character’s brother joined is going to be playing a bigger role starting next session. Could you write ‘em up? Ideology, leaders, that kind of thing?”) But it can scale all the way up to troupe-style play, where players might take total control over specific aspects of the world and even take over the role of GM when those parts of the game world come up in play.

The rich options available to this style of play deserve lengthy deliberation in their own right. For our present discussion, it suffices to say that while this is in most ways functionally identical to description-on-demand (the player is taking authorial control beyond the scope of their character), in actual practice there’s a significant difference: Players don’t feel stressed or put on the spot (because they have plenty of time to carefully consider things). And many players don’t feel that inter-session discussions are as disruptive or dissociative as stuff happening in the middle of a session (because they aren’t being yanked in and out of character).

Go to Part 12: Mail Carrier Scenario Hooks