This will probably be the most controversial entry I write for the GM Don’t List, because there are a lot of players who absolutely LOVE this. And if the players love it, why wouldn’t you do it?

Well, try to bear with me because we’ll get to that.

The technique we’re talking about is description-on-demand: The GM directs an authorial question at a player, giving them narrative control to define, describe, or determine something beyond the immediate control of their character. Examples include stuff like:

- What is Lord Fauntleroy’s deepest secret?

- You open the door and see Madame DuFerber’s bedroom. What does it look like?

- Okay, so you pull him off to one side, confess your love to him, and demand to know if he feels the same way. What does he say?

- What does Rebecca [your PC] know about the Dachshund Gang? Who’s their leader?

- Robert, tell me what the name of the mountain is.

- Okay, you find some juicy blackmail on Mayor McDonald. What is it that he’s done? What evidence do you find?

If you haven’t encountered this technique before, the key thing to understand is that none of the characters being defined here are PCs: The GM isn’t asking Lord Fauntleroy’s player what their character’s deepest secret is. They’re asking the players to step out of their character and create an element of the game world external to their character (often in direct response to their character taking interest in that element of the game world).

It’s description-on-demand because the GM is demanding that a player provide description.

MANY PLAYERS DON’T LIKE IT…

Description-on-demand tends to be a fad that periodically cycles through the RPG meme-sphere. When it does so, the general perception seems to be that every player thinks this is the greatest thing since chocolate-dipped donuts.

So let’s start there: This is not true. Many players do love it. But many players DO NOT. In fact, a lot of players hate it. There are a significant number of players for whom this is antithetical to the entire reason they want to play an RPG and it will literally ruin the game for them.

I’m one of those players. I’ve quit games because of it and have zero regrets for having done so.

So, at a bare minimum, at least take this lesson away with you: Check with your players before using description-on-demand. Because it can absolutely be a poison pill which will ruin your game for them.

Okay… but why do they hate it?

A brief digression: If you’re not familiar with the distinction between roleplaying games and storytelling games, I recommend checking out Roleplaying Games vs. Storytelling Games. The short version is that roleplaying games feature associated mechanics (where the mechanical choices in the game are directly associated to the choices made by your character, and therefore the act of making mechanical choices in the game – i.e., the act of playing the game – is inherently an act of roleplaying) and storytelling games feature narrative control mechanics (where the mechanics of the game are either about determining who controls a particular chunk of the narrative or about determining the outcome of a particular narrative chunk).

When I’m playing a roleplaying game (as opposed to a storytelling game), I am primarily interested in experiencing the game world from the perspective of my character: I want to experience what they experience, make the decisions that they would make, and vicariously experience their fictional life. The reason I want this experience can be quite varied. Roleplaying can be enjoyable in a lot of different ways (catharsis, escapism, experimentation, sense of wonder, joy of exploration, problem-solving, etc.) and the particular mix for any particular game or moment within a game can vary considerably.

Description-on-demand, however, literally says, “Stop doing that and do this completely different thing instead.”

This is not only distracting and disruptive, it is quite often destructive. There are several reasons for this, but the most significant and easy to explain is that it inverts and negates the process of discovery. You can’t discover something as your character does if you were the one to authorially create it in the first place. This makes the technique particularly egregious in scenarios focused on exploration or mystery (which are at least 90% of all RPG scenarios!) where discovery is the central driving force.

Not all players who dislike description-on-demand hate it as much as I do. Some will be merely bored, annoyed, or frustrated. Others will become stressed, anxious, or confused when being put on the spot. Some will just find their enjoyment of the game lessened and not really be able to put their finger on why. But obviously none of those are good outcomes and you need to be aware that they’re a very real possibility for some or all of the players at your table before leaping into description-on-demand.

…BUT SOME PLAYERS DO

So why do some players love this technique?

And they clearly DO love it. Some enjoy it so much that they’ll just seize this narrative control for themselves without being prompted by the GM. (Which can cause its own problems with mismatched expectations, but that’s probably a discussion for another time.)

So… why?

If we keep our focus on the tension between discovery and creation, it’s fairly easy to see that these are players who don’t value discovery as much. Or, at least, for whom the joys of creation outweigh the joys of discovery.

I’m one of those players. When I’m playing a storytelling game, I love being offered (or taking) narrative control and helping to directly and collectively shape the narrative of the world.

…

… wait a minute.

How can both of these things be true? How can I both hate it and love it?

Well, notice that I shifted from talking about roleplaying games to talking about storytelling games.

Here we get to the crux of why description-on-demand is a poor GMing technique. Because while there are times I prefer to be focused on in-character discovery, there are ALSO times when I’m gung-ho for authorial creation. And when that happens, description-on-demand in a traditional RPG is still terrible.

Remember that this technique gives us the opportunity to experience the joy of creation, but does so only by destroying the joy of discovery. There is an inherent trade-off. But when it comes to description-on-demand, the trade-off sucks. I’m giving up the joy of discovery, but in return I’m not getting true narrative control: Instead, the GM arbitrarily deigns to occasionally ask my input on very specific topics (which may or may not even be something that I care about or feel creatively inspired by in the slightest).

Description-on-demand techniques in an RPG dissociate me from my character while offering only the illusion of control.

In an actual storytelling game, on the other hand, I have true narrative control. The structure and mechanics of the game let me decide (or have significant influence over) when and what I want narrative control over. This is meaningful because I, as a player, know which moments are most important to my joy of discovery and which ones aren’t. (This is often not even a conscious choice; the decision of when to take control and when to lean back is often an entirely subconscious ebb-and-flow.)

Note: This discussion is largely assuming storytelling games in which players strongly identify with a specific character (“their” character, which they usually create). There are many other storytelling games – like Once Upon a Time or Microscope – in which this is not the case. In my experience many of those games still feature a tension between discovery and creation, but the dynamics are very different in the absence of a viewpoint character.

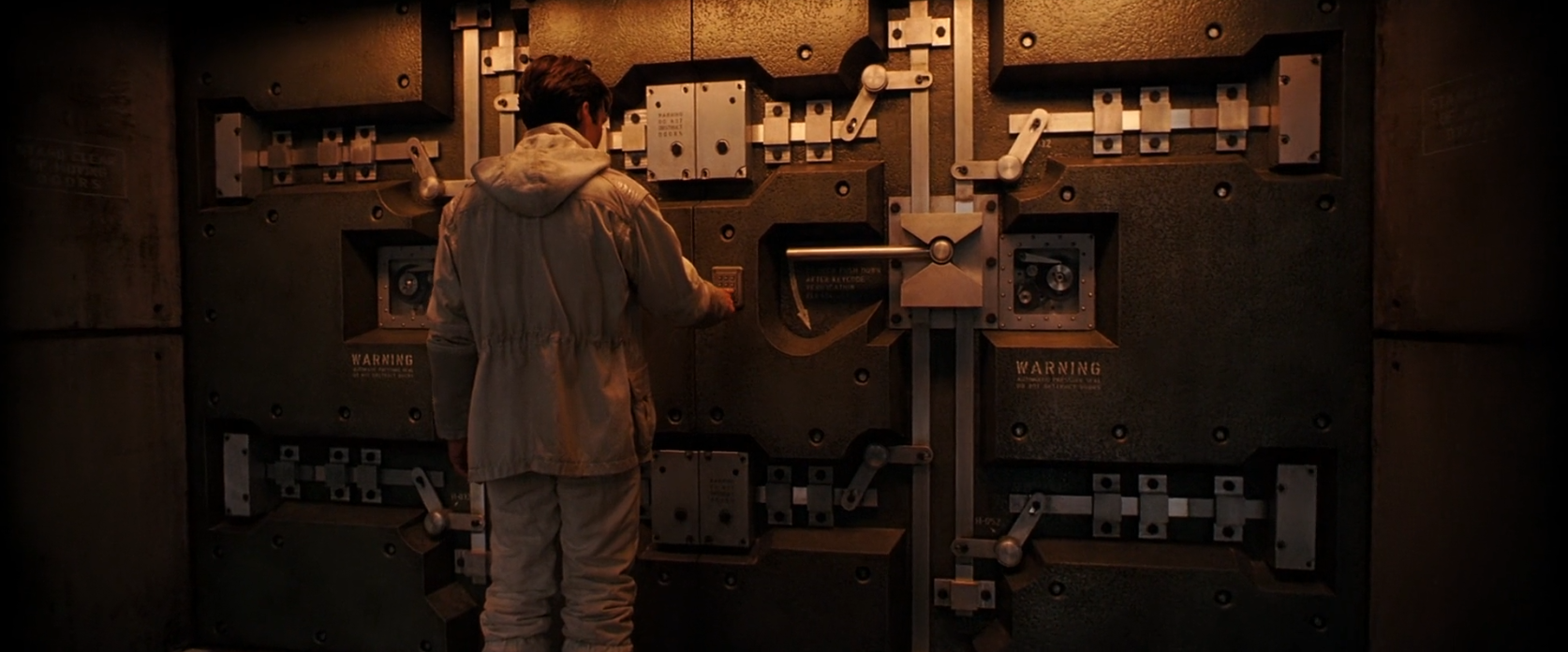

Towards the end of the movie Inception, Eames looks towards the dream vault they’ve been trying to break into for basically the entire movie and says, “It’s a shame. I really wanted to know what was going to happen in there. I swear we had this one.”

Now, imagine the vault door opening. And the GM says: “Okay, Eames, tell me what you see in there!”

For one player, this is great! The importance of this vault has been relentlessly established. The entire narrative has been pushing towards this revelation and now THEY have the opportunity to create what’s inside it!

For another player, this is a disastrous, gut-wrenching disappointment. They’ve spent all this time anticipating this moment; speculating about what the vault might contain, imagining different possibilities, parsing together clues to try to figure it out. And now they’re going to find out! And, instead, the GM announces that there was never any solution to this riddle. There was no plan. No mystery to be solved. Just an empty madlibs puzzle waiting to be filled. “I really want to find out what’s in that vault,” but instead, “Nope, you don’t get what you want. In fact, you have to actively participate in disillusioning yourself.”

For a third player, they don’t really care about having narrative control, but they don’t really have any strong ideas about what should be in the vault and aren’t interested in making a creative decision about that.

And here’s the key thing: You have absolutely no way of knowing which player is which.

In fact, the answer can very easily change from one moment to the next. One player may want an in-character pay-off for the mystery of the vault, but has strong opinions on what Lord Fauntleroy’s deepest secret is and would love to define that. But another may well feel the exact opposite, while a third has no interest in either, and a fourth will be disappointed by any player defining what’s in the vault, because it’ll reveal there wasn’t a canonically true answer.

(And, yes, I have very deliberately chosen a narrative in which the characters do, in fact, have influence — albeit an indirect one — over what the vault will contain. I want you to challenge your preconceptions within the uncertainties of this liminal space. While you’re here, if you’re familiar with the movie, ask yourself whether your opinion on this interaction would be different if the GM was asking Robert Fischer’s player what was inside the vault instead of Eames’ player. Do you see how a different player of Robert Fischer might want the exact opposite answer?)

The cool thing about most narrative control mechanics is that they give you the ability to say, “This is what I care about. This is what I want to create.” And, conversely, “This is not something I care about. This is, in fact, something I DON’T want to be responsible for creating.”

CONCLUSION

Here’s my hot take.

I think description-on-demand is primarily — possibly not exclusively, but primarily – popular with players who have never played an actual storytelling game or who would desperately prefer to be playing one.

Because the thing that description-on-demand does — that little taste of narrative control that many players find incredibly exciting — is, in fact, an incredibly shitty implementation of the idea.

If you’re interested in an RPG, this is like playing Catan and having the host demand that you roleplay scenes explaining your moves in the game. (Just play an actual RPG!)

On the other hand, if you’re craving an STG, then description-on-demand in a traditional RPG is like playing co-op with an alpha quarterback who plays the entire game for you, but then occasionally says, “Justin, why don’t you choose the exact route your meeple takes to Sao Paolo?” and then pats themselves on the back for letting you “play the game.”

(This applies even if you’re playing an RPG and are just interested in adding a little taste of narrative control to it: You would be better off grafting some kind of minimal narrative control mechanic onto the game so that players can, in fact, be in control of their narrative control.)

To sum up, the reason description-on-demand makes the GM Don’t List is because:

- If that’s not what a player wants, it’s absolutely terrible.

- If it is what a player wants, it’s a terrible way of achieving it.

BUT WAIT A MINUTE…

There are several other techniques which are superficially similar to description-on-demand, but (usually) don’t have the same problems. Let’s briefly consider these.

FENG SHUI-STYLE DESCRIPTION OF SETTING. Robin D. Laws’ Feng Shui was a groundbreaking game in several ways. One of these was by encouraging players to assert narrative control over the scenery in fight scenes: If you want to grab a ladder and use it as a shield, you don’t need to ask the GM if there’s a ladder. You can just grab it and go!

Notably this is not on-demand. Instead, the group (via the game in this case) establishes a zone of unilateral narrative control before play begins. It is up to the players (not the GM) when, if, and how they choose to exercise that control. Players are not stressed by being put on the spot, nor are they forced to exert narrative control that would be antithetical to their enjoyment.

EXTENDED CHARACTER CREATION: This is when the GM asks a question like, “What’s Rebecca’s father’s name?” Although it’s happening in the middle of the session, these questions usually interrogate stuff that could have been defined in character creation.

This generally rests on the often unspoken assumption that the player has a zone of narrative control around their character’s background. Although this narrative control is most commonly exercised before play begins, it’s not unusual for it to persist into play. (Conversely, it’s similarly not unusual for players to improvise details from their character’s background.) This can even be mechanically formalized. In Trail of Cthulhu, for example, players are encouraged to put points into Languages without immediately deciding which languages they speak. (Each point can then be spent during play to simply declare, “I speak French,” or the like.)

Because it’s unspoken, however, both the authority and boundaries of this zone can be ill-defined and expectations can be mismatched. (The problems that can result from this are probably yet another discussion for another time.)

There’s also a gray zone here which can easily cross over into description-on-demand. “What’s your father’s name?”, “Describe the village where you grew up,” and “You grew up in the same neighborhood as the Dachshund Gang, so tell me who their leader is,” are qualitatively different, but there’s not necessarily a hard-and-fast line to be drawn.

RESOLUTION OF PLAYER-INITIATED ACTION: So if saying, “You find some juicy blackmail on Mayor McDonald. What is it that you’ve caught him doing?” is description on demand, then what about when the GM says, “You deal 45 hit points of damage. He’s dead. Describe the death blow,” that must also be description-on-demand, right? I mean, the GM even said the word “describe!”

There is some commonality. Most notably, you’re still putting players on the spot and demanding specific creativity, which can stress some players out in ways they won’t enjoy. But this effect is generally not as severe, because the player has already announced their intention (“hit that guy with my sword”) and they probably already have some visualization of what successfully completing that intention looks like.

In terms of narrative control, however, there is a sharp distinction: You are not asking the player to provide a character-unknown outcome. You are not dissociating them from their character.

This is true in the example of the sword blow, but may be clearer in a less bang-bang example. Consider Mayor McDonald and the difference between these two questions:

- “You find some juicy blackmail on Mayor McDonald. What is it that you’ve caught him doing?”

- “You find some juicy blackmail on Mayor McDonald. He’s been cheating on his wife with a woman named Tracy Stanford who works in his office. How did Rebecca find this out?”

In the first example, the GM is asking the player to define an element of the game world outside of their character and their character’s actions. In the second example, the GM has defined that and is instead asking them to describe what their character did. Although it’s become cognitively non-linear (the player knows the outcome, but is describing actions their character took before they knew the outcome), it is not dissociated from the character.

The same is true of the sword blow: The mechanics say the bad guy dies; take a step back and roleplay through how that happened.

(For a longer discussion of closely related stuff, check out Rulings in Practice: Social Skills.)

WORLD DEVELOPMENT BETWEEN SESSIONS: As a form of bluebooking, players may flesh out elements of the campaign world between sessions.

Sometimes this is just a more involved version of extended character creation. (“Pete, it looks like that Order of Knighthood your character’s brother joined is going to be playing a bigger role starting next session. Could you write ‘em up? Ideology, leaders, that kind of thing?”) But it can scale all the way up to troupe-style play, where players might take total control over specific aspects of the world and even take over the role of GM when those parts of the game world come up in play.

The rich options available to this style of play deserve lengthy deliberation in their own right. For our present discussion, it suffices to say that while this is in most ways functionally identical to description-on-demand (the player is taking authorial control beyond the scope of their character), in actual practice there’s a significant difference: Players don’t feel stressed or put on the spot (because they have plenty of time to carefully consider things). And many players don’t feel that inter-session discussions are as disruptive or dissociative as stuff happening in the middle of a session (because they aren’t being yanked in and out of character).

What a great analysis. I can see how this can apply to solo roleplaying as well. I’ve dabbled in solo but the ‘creation at the cost of discovery’ really took the wind out of what I was looking for. I can see that maybe leave the outcomes to the oracles / game mechanics and I can just provide the why/how (unless I don’t care and just want to move on to something else).

A great article! I really like it (maybe in part because I don’t like this technique and felt I was alone in this).

But there is I think one more caveat. One of your examples: “What does Rebecca [your PC] know about the Dachshund Gang? Who’s their leader?” would be really ok for me if GM treated it only as a character’s knowledge that can be not true. It is a bit what you call ‘extended character creation’. The player tells what his/her character knows about one element of the game world. GM can use it as an inspiration, but can (and should) twist it a bit to maintain the joy of discovery for players.

I was all set to ask “What about «how are going to do this?»” .. but then you included that in the exceptions appendix.

So, instead, what about the case of turning to a different player (who isn’t actively involved in this particular moment) and asking them to fill in some minor descriptive detail (e.g. the colour of the gemstone the primary player just found)

PC1: I open the lootbox.

DM: OK .. oh, wow, nestled on a bed of shiny coins there is a massive gem, size of a small egg, and is a translucent ..

DM «stage-whispers to PC2» what colour?

PC2: «stage-whispher» uh, blue?

DM: «back to PC1» .. and is a translucent deep blue colour. What do you do?

@Eric: I’m not Justin, but I can imagine his answer.

This is again just the illusion of narrative control, especially when you specify “minor descriptive detail”, as in, something completely irrelevant. The player is used merely as a source of creativity out of what will appear to be just GM laziness.

As a GM I usually like to give narrative control to the players. This allows me to add variety on the flow of a session and actually build on the idea that the game is a conversation. But I guess that is a consequence of the games I play. Blades in the Dark, Tales from the Loop, Dungeon World, etc. In those games it never felt weird to ask “Okay, you find some juicy blackmail on Mayor McDonald. What is it that he’s done? What evidence do you find?” or something similar exactly because we are playing to find out. Everyone isn’t excited about what he’s done but instead what consequences will come out of it. A player saying “Oh man, I think he killed someone” makes everyone excited in the same way.

For me giving narrative control to the players is a amazing tool that you need to use with caution if you are playing other games. BUT is a amazing tool nonetheless. Just make sure the system you are using allow these kind of things (and you explain to the group the agenda and principles that reinforce this idea).

Well that came across as unpleasantly vitriolic….

Very interesting. I used this technique very sparsely and it always seemed unsatisfying. This article definitely clarifies why it never seemed to fit. Excellent article, hope to see more in this series.

@Allen: I agree that the end effect is often poor, but I think GMs who use this technique aren’t being lazy or even trying to cede narrative control. They are thinking it’s a way to keep players who aren’t in the current scene engaged in the game. That might be why it comes off as patronizing.

Great discussion as always.

This is why story games are not great at mystery or horror. There’s an inherent trade off between player narrative control and the tension of discovery and exploration.

While I agree that foisting the responsibility of narrative control on the players without a predetermined assumption of who controls which realms of narrative agency (backstory, character details, etc) I reject the act is something dissociated or non-diegetic.

For example: the player characters rescue a prisoner who used to work for the villain, and is willing to help the group. They know the password to the villain’s lair, are now under the player’s control.

Well, where’s the base, what’s the password? Ask the NPC. Notice that we never stopped roleplaying? Now the NPC has a backstory the players are responsible for. A more improv friendly group can generate this material on the fly, a different group can

decide between sessions, or can break from direct role play to create a backstory.

But this is no different from a character dying and introducing a new one on the fly, and entirely in the purview of an RPG.

Likewise, the player characters search the room. One character emphasizes reviewing the bookshelves. They discover a journal of a minor but notable NPC, like a healer.They take an intelligence check to review it hastily. Within, they discover a secret that if presented to the NPC with a successful social check will grant them free healing within that region, to a prescribed limit (D&D: only CLW, three times a day, no raise dead).

Well what’s the secret? Doesn’t matter, it just gets you free healing if you pass a social check, you can describe what you find in the book.

Same thing as telling a player to describe a kill: clear mechanical resolution, the narrative is simply vague and on the player. No more dissociation than having the player roll to search the room and asking them to narrate the action of searching.

You, as a player, may prefer “discovering” information that is provided by the GM’s notes, the GM improvising or the GM rolling off a table, but there’s no reason that narrative information cannot come from a player, improvising what they read, or rolling on a table of their own, that prevents it from being an act of roleplaying: your character is the one reading after all. The GM narrating what you read aloud is arguably LESS roleplaying, as you’re now a passenger on that set of rails, watching the GM perform live theatre until you get to have the agency back.

What do you think about the indie role-playing games that seem to bridge the gap between storytelling and traditional rpgs? Im thinking of things like Dungeon World and Burning Wheel here, where you have the traditional I’m creating a character and playing them but the some rules also encourage creating the world around you as well (dungeon worlds draw maps but leave blanks, and the fact that BWs beliefs work beat when you are declaring something about the world)

I don’t really disagree with any of that, but for me there’s an angle that’s been left out. When things in the game have really gone into left field, sometimes I draw a blank on inventing-on-the-spot something interesting the PCs have just found. And rather than officially say they’ve found something lame and generic, I’ll go to the table and try to get a better idea. Sometimes it makes sense to ask a specific person, either because I think it’s particularly relevant to them or because it’s the kind of thing where they usually have good ideas, or sometimes I’ll flat out say “I think there should be something cool in this box — anyone have a good idea?” In the comments above this has been called “GM laziness”, but sometimes you just draw a blank. And if you aren’t railroading, sometimes the game will leave the map.

Relevant, though, is that this is an improv technique. Either everyone knows that we’ve taken a hard left and are chasing something I did *not* have prepared, or the whole game is plain being made up as we go along. (We are adults with jobs. Sometimes the choice is between GMing with no prep or not playing at all.)

@Fistan: I have several issues with the scenarios you described.

First, giving the PCs complete control over a villain’s former minion would be a missed opportunity. This person used to work for the villain — who knows if they can be trusted? If you treat them like just a backup PC, you’re sucking all the suspense out of the situation.

Secondly, the password may be an insignificant detail (like “What color is the gem you found?”), but the location of the villain’s base is a pretty big deal. Imagine doing the same thing in a murder mystery scenario where the PCs are detectives. Imagine after describing the murder scene and introducing all the suspects, the GM turns to the players and asks, “Who do you think did it?” Imagine if the players name their prime suspect, and the GM says “Okay, we’ll make them the murderer then.” Do you think the players would feel motivated to keep investigating?

I’m not saying there’s not enjoyment in *writing* a murder mystery, but it’s a different sort of enjoyment than you get from *reading* a murder mystery, and you’d feel cheated if you got halfway through a mystery novel and found that the author expected you to write the ending yourself.

Sidebar: I know there are games that leave certain plot elements up to chance, instead of the GM. For instance, I recently played Curse of Strahd, which includes a “Tarokka” reading to determine the locations of several key plot elements. If you think that’s no different from letting the players decide, consider this:

You know those gift exchanges where you bring a cheap wrapped gift, toss it on a pile, and then draw numbers to decide who gets to pick first from the pile? (Usually you’re allowed to “steal” a gift that someone else has already unwrapped rather than picking blindly, but that’s not really relevant to the analogy.) Nobody knows what gift you’re going to end up with until you pick it, not even the person who brought the gift.

Now imagine that, instead of wrapping their gifts and tossing them on the pile, everyone keeps their gifts with them and just tosses an empty gift-wrapped box on the pile. And when it’s your turn to pick, you choose one of the empty boxes, open it up, and stick your own gift in it. Does that sound like fun?

@ Fistan, continued:

“The GM narrating what you read aloud is arguably LESS roleplaying”

How so? Because the player’s not the one doing the reading? Roleplaying is reacting to a situation the way that you think your character would. In most games, most of what you know about that situation is conveyed verbally rather than visually, but it’s no less roleplaying because you hear it with your ears instead of seeing it with your eyes. (And if it’s that big a deal to you, just ask your GM for a written handout.)

The PC opens a book, the player learns what they find there, and they decide what the PC does about it. That is roleplaying! But if the PC opens a book and the *player* decides what they find there, the player is no longer making decisions as the PC would; they’ve stepped outside of the role of the PC and assumed an authorial role. That’s the very definition of dissociated.

Now, some games (Feng Shui, Adventure!, Fate) have mechanisms that allow the player to exert authorial control, but that doesn’t make the act less dissociated. And the key difference is that those rules are exercised at the player’s discretion, not the GM’s. The player has buy-in, instead of being yanked forcibly out of character with no warning.

“No more dissociation than having the player roll to search the room and asking them to narrate the action of searching.”

If you can’t see a difference between the player describing how they search the room and the player deciding what they find, then I don’t know what to tell you.

@Wyvern

You missed my point.

“ If you can’t see a difference between the player describing how they search the room and the player deciding what they find, then I don’t know what to tell you.”

But I have told the player what they find: information that provides free healing in the town of Omelette. The player is the one answering the How? or Why?, but the What? is clearly defined.

Much the same as “You discover a work of art worth 200 dollars” and not concerning myself with whether it’s a painting, a statue or a sonnet, and whether the value is in its creator, it’s antiquity or its materials. I’m a-ok with the PC stating that this is an original Roophotello, that its a solid gold dragon statue or that it’s a carving from a long forgotten tribe. None of that changes the value of the item, or changes the fact that it’s a work of art, which will limit who will value it in trade.

‘ “The GM narrating what you read aloud is arguably LESS roleplaying”

How so? Because the player’s not the one doing the reading?’

Yes. Watching live theatre isn’t roleplaying. A GM monologing or dictating character action removes agency from a player. The player should be describing how they walk down a hall, how they attack a monster, what their spell looks like and what they read.

A GM taking control of that stops the roleplaying, and turns it into a story telling game.

“ First, giving the PCs complete control over a villain’s former minion would be a missed opportunity. This person used to work for the villain — who knows if they can be trusted? If you treat them like just a backup PC, you’re sucking all the suspense out of the situation.”

I disagree, but I have groups that don’t mind party conflict. If Alex controls the turncoat minion, then Taylor and Bren’s characters can be suspicious, especially if Alex decides that the NPC might be lying. Now the tension is between the players and their characters, rather than the players and the GM, who is merely adjudicating their actions, rather than interfering with a DM NPC and stealing the spotlight.

Perhaps your groups hate player tension, so this isn’t a move for them.

“ the location of the villain’s base is a pretty big deal. Imagine doing the same thing in a murder mystery scenario where the PCs are detectives.”

Yep. And the players solve the mystery and receive the password.

You’re mistaking what the DM NPC is: they are the boon. The players have already done the investigation, but instead of killing the ogre bandits and finding the password in a letter in a chest in the leaders tent, they find the NPC in a cage. Now the password is interactive, offers much more opportunities for roleplaying and presents the very tension you describe: can we trust them? Are they truly a traitor, or are they a spy? Etc.

Point is, the mechanical and narrative function is identical: this “noun” provides this “information to unlock a gated part of the world”. But “letter” that contains “the password” and “map” that “reveals the secret entrance” is instead “servant” that “can lead the PCs”.

See how they’re exactly the same?

The NPC simply has more fertile roleplaying elements, rather than a “blue pass card” which is a pretty dull prize for solving a mystery.

“The GM narrating what you read aloud is arguably LESS roleplaying”

There is a solution that neither forces a player to suddenly start being creative about something that isn’t their character’s actions, nor turns this into a one-man GM show.

It’s called a handout.

I think Colin R and Gabriel manage to say more clearly and concisely what Fistan is trying to get at. There is a gaming style in which “description on demand”, or more accurately “description by brainstorming” can be acceptable even without clear narrative control mechanics.

That is when the entire plot is agreed to be more improv and there is no pre-fixed situation the GM has prepped for the players to untangle. Blades in the Dark is a perfect system for this, given that is has A) The bolded words “No one is in charge of the story” right in its first chapter. This is a mission statement that the players need to buy in. It’s something that needs to be mentioned in Session 0. B) those words are followed by a rule about judgment calls: Who has the final say about what aspects of the story. Those could be argued to be narrative control rules. C) it’s gameplay loop isn’t focused on world details. For BitD, the relevant aspects of a score are its target faction, the outcome it has on the crew, and the harm and stress the players accrue during it. The actual *object* of the score is not important. For the rules, whatever the players steal, smuggle or kill is just a McGuffin.

But this isn’t the same gameplay you get out of DnD. “I search the room” is not a phrase uttered in BitD, and if, not with the same intent as during a dungeon crawl, because Blades in the Dark is not a game of exploration.

This article really helped me. I have been vaguely thinking about this, but didn’t have the framework to really comprehend and express what it was.

I love when the GM lets me create stuff. And as a GM I love when they players volunteer cool new ideas for the setting. But it’s one thing when it is somehow connected to the character, and another when it is something external. It breaks the agreed upon division of control. It’s not fun to tell yourself what you discover, to challenge yourself, to control both sides of a conversation. It takes away from the collective elements of collective creation – the part where you need someone else to fill it in for you.

“But I have told the player what they find: information that provides free healing in the town of Omelette…. Much the same as “You discover a work of art worth 200 dollars” and not concerning myself with whether it’s a painting, a statue or a sonnet…”

These are strawman arguments. I didn’t bring up your free healing example because I don’t really have a problem with it. Nor do I have a problem with the players improvising details about the treasure that they found.

“A GM monologing or dictating character action removes agency from a player.”

Player: I read the journal.

GM: Okay, here’s what it says…

How is this “dictating character action”? The player is the one who chose to read the journal; the GM just told them what they found there.

Player: I read the journal.

GM: Okay, what does it say?

Player: What? How would I know? Aren’t *you* supposed to tell *me* that?

Usually when I have my PC read something in a game, it’s because I’m looking for information. It would be very off-putting to be told that information doesn’t exist and I have to make it up myself.

“The player should be describing how they walk down a hall, how they attack a monster, what their spell looks like and what they read.”

The player describes how they walk down a hall, but the GM is the one who tells them that the hall exists and where it leads. The player describes how they attack a monster, but the GM decides what kind of monster it is and what it’s capable of. The player may describe what the spell looks like, but the rules define what the spell can do. The player decides what books to read, and the GM tells them what’s in those books.

If the *players* are deciding where the hallway leads and which rooms have monsters in them, then they’re *not* playing a roleplaying game, they’re playing a storytelling game. And there’s nothing wrong with that, if it’s what they signed up for.

“A GM taking control of that stops the roleplaying, and turns it into a story telling game.”

The GM taking control of the player’s *actions* is off-limits. The GM describing the *results* of those actions is what roleplaying is all about. When the *players* are asked to decide these things, *then* it’s a storytelling game. It’s hard to discuss this with you when you’re living in Opposite Land.

“If Alex controls the turncoat minion, then Taylor and Bren’s characters can be suspicious,”

That’s an interesting idea, and I don’t see any problem with it if the players are into it. But…

” the GM, who is merely adjudicating their actions, rather than interfering with a DM NPC and stealing the spotlight”

Do you not realize how ridiculous that sounds? How dare the GM control non-player characters!

“And the players solve the mystery and receive the password.”

You haven’t really addressed my point at all. I don’t care whether they find the password on a letter in a chest, or by interrogating a captured prisoner. That’s another strawman argument. And I don’t care if they get to decide whether the password is “crossbones” or “leviathan”.

But it’s another matter altogether for them to decide where the villain’s base is, or who killed Mr. Boddy. Leaving those things up to the players is fine in a storytelling game, but not a roleplaying game. When I’m trying to *solve* a mystery, I don’t want to *invent* the solution myself.

Addendum: I should clarify why I’m making such a big deal about this. If you and your gaming group enjoy the sort of collaborative improvisation that you’re describing, more power to you. I’m not saying that it’s badwrongfun, or that RPG and STG should never be mixed.

However, for you to say that it’s not dissociated only shows that you don’t understand what Justin means when he uses the term. So let me spell it out for you:

When a player decides what the PC does and how they do it, they are making decisions as if they were the PC, ergo they are playing a role. However, if you ask the player to decide what the password is, or where the villain’s base is, or what books are in the villain’s library, you are asking them to decide things that are beyond the PC’s ability to control. In that moment, they are stepping out of the role of the PC and assuming an authorial role instead. They have dissociated themselves from the PC.

Now again, if you and your players enjoy that, there’s nothing wrong with it. But there a difference between saying that you enjoy doing X, and saying that you’re *not* doing X when you clearly are. The latter situation means either that you’re a liar, or that you don’t *realize* that you’re doing X (possibly because you don’t understand what X actually is).

It’s perfectly fine to think that chocolate and peanut butter taste great together. But if you think that chocolate and peanut butter are the same thing, it’s going to cause you problems when you try cooking for someone who’s allergic to peanuts.

@Wyvern

“When a player decides what the PC does and how they do it, they are making decisions as if they were the PC, ergo they are playing a role.”

Exactly. Which is why this is true:

Player: I read the journal

GM: Your character has now acquired the knowledge of how to get free healing in the village of Omelette, once per day. 2d4HP.

The PC now knows how to get the healing in Omelette. How do they get that healing? The same way they slay some orcs. Mechanics are defined, the player narrates how the mechanics are resolved, then mechanics are resolved.

But the move is entirely associated with the reality of the game world. The book told the PC how to do the *Action* to get the *Noun*. The player can now declare the character does the *Action* to get the *Noun*. Nothing dissociated.

“However, if you ask the player to decide what the password is, or where the villain’s base is, or what books are in the villain’s library, you are asking them to decide things that are beyond the PC’s ability to control.”

Incorrect. The PC has control of the information, they have acquired it. And if the PC has it, the player has it too.

So the password is entirely associated, because the PC has learned it.

“In that moment, they are stepping out of the role of the PC and assuming an authorial role instead. They have dissociated themselves from the PC.”

No, they haven’t stepped outside the PC. The PC has the knowledge. They gained it by doing something in the game.

That’s where this “associated mechanics” purity test falls apart. If a PC knows something, then it’s associated. If it’s associated, it’s not really a story telling game, is it.

Alexander frames this as the GM making a demand of a player, but this is a coy attempt to curtail the narrative agency of a player.

My two examples, an NPC with specific mechanical knowledge and an object that grants a specific mechanic that are only vaguely defined narratively debunk this association fallacy.

PC does a thing. GM defines the outcome as something that now permits a mechanic. PC now can access the mechanic.

“It’s perfectly fine to think that chocolate and peanut butter taste great together. But if you think that chocolate and peanut butter are the same thing, it’s going to cause you problems when you try cooking for someone who’s allergic to peanuts.”

The problem you’re encountering is that you are using an Actor/Author fallacy.

Roleplayers are neither. They are Improvisers, who share traits of both, but also possess traits alien to both.

This isn’t Peanut Butter or Chocolate. This is Fudge.

Or more specifically, Story Telling games are Fudge, and Roleplaying games are Chocolate Fudge.

The chocolate is the “associated” mechanics borrowed from wargames, I suppose.

Which is why I point out that this little nugget of advice fails by its own criteria. PCs inherently have knowledge the Players do not, but thats still associated, and the players, who have authorial control of their character, should absolutely be allowed to define how the mechanic operates narratively, as long as it follows the rules. Purple Tieflings and Dragonborn with tails shouldn’t be a thing the GM discourages, and Alexander is advocating for that here.

And granting a player a sword +1 does not compel the GM to provide the Tolkienese flavour text telling you for 8 hours how this was forged by the Duloquandi dwarves, who were an offshoot of the Hambenduri clan who warred against the traitor Queen of Umbat and was wielded by the champion Dealio, who fell fighting Six and twenty Goburks, who were Orcs, called Goblins by folk of the south, but GobHoblins by the Duloquandi Dwarves, but only those who remained in the Mines of Dwimmergoon after the fall of Drakulsmirf…..

And it should also not prohibit a PC from providing that very flavour text.

RPGs are collaborations, not dictations, and telling a GM that permitting their players to collaborate is bad, and even fails some kind of purity test (which it doesn’t, by it’s own parameters of association)

s in a story telling game” isn’t helpful

@Wyvern

“When a player decides what the PC does and how they do it, they are making decisions as if they were the PC, ergo they are playing a role.”

Exactly. Which is why this is true:

Player: I read the journal

GM: Your character has now acquired the knowledge of how to get free healing in the village of Omelette, once per day. 2d4HP.

The PC now knows how to get the healing in Omelette. How do they get that healing? The same way they slay some orcs. Mechanics are defined, the player narrates how the mechanics are resolved, then mechanics are resolved.

But the move is entirely associated with the reality of the game world. The book told the PC how to do the *Action* to get the *Noun*. The player can now declare the character does the *Action* to get the *Noun*. Nothing dissociated.

“However, if you ask the player to decide what the password is, or where the villain’s base is, or what books are in the villain’s library, you are asking them to decide things that are beyond the PC’s ability to control.”

Incorrect. The PC has control of the information, they have acquired it. And if the PC has it, the player has it too.

So the password is entirely associated, because the PC has learned it.

“In that moment, they are stepping out of the role of the PC and assuming an authorial role instead. They have dissociated themselves from the PC.”

No, they haven’t stepped outside the PC. The PC has the knowledge. They gained it by doing something in the game.

That’s where this “associated mechanics” purity test falls apart. If a PC knows something, then it’s associated. If it’s associated, it’s not really a story telling game, is it.

Alexander frames this as the GM making a demand of a player, but this is a coy attempt to curtail the narrative agency of a player.

My two examples, an NPC with specific mechanical knowledge and an object that grants a specific mechanic that are only vaguely defined narratively debunk this association fallacy.

PC does a thing. GM defines the outcome as something that now permits a mechanic. PC now can access the mechanic.

“It’s perfectly fine to think that chocolate and peanut butter taste great together. But if you think that chocolate and peanut butter are the same thing, it’s going to cause you problems when you try cooking for someone who’s allergic to peanuts.”

The problem you’re encountering is that you are using an Actor/Author fallacy.

Roleplayers are neither. They are Improvisers, who share traits of both, but also possess traits alien to both.

This isn’t Peanut Butter or Chocolate. This is Fudge.

Or more specifically, Story Telling games are Fudge, and Roleplaying games are Chocolate Fudge.

The chocolate is the “associated” mechanics borrowed from wargames, I suppose.

Which is why I point out that this little nugget of advice fails by its own criteria. PCs inherently have knowledge the Players do not, but thats still associated, and the players, who have authorial control of their character, should absolutely be allowed to define how the mechanic operates narratively, as long as it follows the rules. Purple Tieflings and Dragonborn with tails shouldn’t be a thing the GM discourages, and Alexander is advocating for that here.

And granting a player a sword +1 does not compel the GM to provide the Tolkienese flavour text telling you for 8 hours how this was forged by the Duloquandi dwarves, who were an offshoot of the Hambenduri clan who warred against the traitor Queen of Umbat and was wielded by the champion Dealio, who fell fighting Six and twenty Goburks, who were Orcs, called Goblins by folk of the south, but GobHoblins by the Duloquandi Dwarves, but only those who remained in the Mines of Dwimmergoon after the fall of Drakulsmirf…..

And it should also not prohibit a PC from providing that very flavour text.

RPGs are collaborations, not dictations, and telling a GM that permitting their players to collaborate is bad, and even fails some kind of purity test (which it doesn’t, by it’s own parameters of association)

All you’ve done is confirm my suspicion that you don’t understand what Justin means when he says dissociated.

“Incorrect. The PC has control of the information, they have acquired it. And if the PC has it, the player has it too.

So the password is entirely associated, because the PC has learned it. … The PC has the knowledge. They gained it by doing something in the game.

That’s where this “associated mechanics” purity test falls apart. If a PC knows something, then it’s associated. If it’s associated, it’s not really a story telling game, is it.”

It isn’t *knowledge* that’s associated or dissociated, it’s *decisions*. When the player decides to interrogate the prisoner to get the password to the villain’s lair, they’re making the same decision the PC might make. But if the player decides what the password is, they’re making a decision the PC couldn’t make. The PC doesn’t have the ability to choose what the villain’s password is (unless they *are* the villain), they have to have that information provided to them from somewhere else.

Now, if you think that there’s nothing wrong with players making dissociated decisions in an RPG, you’re welcome to that opinion. But you should own it, instead of trying to deny that’s what you’re doing.

“Roleplayers are neither. They are Improvisers, who share traits of both, but also possess traits alien to both.”

They’re are two kinds of improv: the kind where the improviser is free to declare facts that are beyond the control of the character they’re portraying (“Suddenly a car comes crashing through the wall!” or “You’re actually my long-lost twin!”) and those where they aren’t. In the latter kind, the improviser is simply an actor without a script. In the former kind, they’re alternating between actor and author.

Either can be fun. But if you thought you signed up for the second kind only to find out your fellow performers are doing the first (and expect *you* to as well), it could be jarring. And if you invite your friends to join you in an improv session without defining the ground rules because you think all improv is the same then there’s going to be confusion.

“This isn’t Peanut Butter or Chocolate. This is Fudge.

Or more specifically, Story Telling games are Fudge, and Roleplaying games are Chocolate Fudge.”

Fudge is just a kind of chocolate. “Chocolate fudge” is redundant. (If it’s got peanut butter in it, then it’s peanut butter fudge.) I have no idea what you’re trying to say here.

Corrections: Technically, it *is* possible to make fudge without any chocolate any it. In which case, it sounds like you’re saying that roleplaying games are a subset of storytelling games. If *that’s* what you meant, I have two responses.

First, it contradicts other statements you’ve made in which you seem to draw a sharp line between the two, such as these:

“A GM taking control of that stops the roleplaying, and turns it into a story telling game.” (If all RPGs are story telling games, an RPG can stop being an RPG, but it can’t *turn into* a story telling game because it already was one.)

“If a PC knows something, then it’s associated. If it’s associated, it’s not really a story telling game, is it.” (If the PC having associated knowledge in an RPG makes it not a story telling game, then that means that *not* all RPGs are story telling games.)

Secondly, it’s technically true that RPGs are “storytelling games” in the sense that they’re games in which you tell a a story. But by that logic, you could argue that Axis & Allies and Clue are RPGs because they’re games in which you play a role (of “Germany” or “Col. Mustard”). But when Justin and I (and others in the hobby) refer to “storytelling games”, we’re talking about something more specific: games such as Fiasco or Once Upon a Time.

I get the feeling you may not be familiar with that kind of game, because you seem to define “storytelling game” as a game in which the GM is the sole storyteller and the other players are passive audience members. That’s the exact opposite of how we’re using the term, and if that’s what you thought we meant, it’s no wonder we keep talking past each other.

“The player should be describing how they walk down a hall, how they attack a monster, what their spell looks like and what they read.”

Wyvern has already addressed the “what they read” part, but as regards the other stuff: in my experience, what’s in the other players’ heads when I declare that I’m swinging my longsword at the dragon is usually better than what I say if I’m forced to provide a flowery description of exactly how I swing it.

I’m not a fan of “How do you want to do this,” personally, for the same reason: if I have to make something up on the spot, it’s likely to be the most prosaic thing you ever heard. “Uh…My arrow goes straight through the ogre’s eye and he falls down like a sack of bricks?” Maybe some people play exclusively with highly skilled instant wordsmiths, but I am decidedly not one.

Anyway, on to my reaction to the post itself:

The “gut-wrenching disappointment” paragraph is a spot-on characterization of my values as a player and why I play these games. I’ve never seen Inception, but I think I get, and empathize with, what that was getting at. If I’m playing a game that involves solving mysteries (which, as mentioned in the post, describes most campaigns to some extent), then I want to feel like I am solving mysteries along with my character. If I’m playing a game set in a royal court beset by intrigue, where you have to be careful about who you trust, then I want to think carefully about who my character should trust!

I can’t really see that happening in a situation where the players’ relationship to information is so open-ended. If the facts on the ground could be retconned at any point (either by the players or the GM), because “wouldn’t it be super dramatic if Lady Evelyn has been a traitor all along?” or whatever, then the idea of our in-character decisions mattering long-term is kind of gone. I no longer feel like I’m navigating the deadly court of intrigue — I might as well be reading about it in a novel, where the protagonists will trust some of the right people and some of the wrong people, and the latter’s betrayals will be revealed right when it’s most dramatic to do so.

One of my favorite things about Justin’s campaign diaries is seeing those moments when the players come up with theories based on the information they have, which he didn’t necessarily see coming, and it changes things going forward. Like when the party discovers a letter between two NPCs about Dominic: they interpret it as being very sinister (although that wasn’t those NPCs’ intention in Justin’s mind!), so Dominic decides to skip his meeting with them and seeks out another NPC’s help instead, which has far-reaching consequences. That’s so cool! The unique thing about this medium is that you can come up with theories about what’s going on in the world and actually make the characters do something about it.

I guess I do t understand why your table isn’t a place where players feel comfortable saying “Nah, I want to be surprised so you go ahead”.

And I’m definitely not sure what sort of anecdata you’re basing your assertion that there’s some silent majority out there that hates this style of play. In the game stores that I owned, where I ran tens of thousands of hours of RPGs from the read-eat of intro D&D games through the most airy-fairy hippie nonsense, giving players a little extra agency has been met with bear-universal approval.

I get that projecting your own taste onto your cultural cohort is a very human thing to do but this is some Epic-level projection you’re engaged in here.

That said, if you hate being offered the chance to share in building the narrative of a read RPG session THAT MUCH, your Immediately rate-quitting any game that offers it is the right thing to do, and has undoubtedly saved a lot of GMs and players who enjoy that style of play a lot of grief.

Leaving tables where you’re not having a good time is something we should make profound efforts to normalize, and that’s my main take-home from this.

@Jim: Please don’t blatantly lie about what I actually wrote. It’s very rude and I have absolutely zero patience for it.

I’m a big fan of the idea of asking players leading questions about the world to help with collaborative world-building, but the players need to be on board with that style of play before you use it. It’s likely not a good fit for traditional RPGs.

There’s a good essay written by John Harper about “The Line” when using this sort of technique:

http://mightyatom.blogspot.com/2010/10/apocalypse-world-crossing-line.html

It feels obvious you don’t like pbta games at all…

I absolutely agree with this! As a new GM for Feng Shui, I initally had the players come up with details during each scene. It was fun at first but it can get slightly out of hand. What I love about FS2 is that the players can add their own color to their relationships with certain characters as well as describe (as detailed as they want) their attacks in combat.

Thanks for writing this article!

[…] Here’s an article that references this approach: https://thealexandrian.net/wordpress/44891/roleplaying-games/gm-dont-list-11-description-on-demand […]

The Angry Gm tackled this issue as well, in an older article. He also characterized it as a tension between expression and discovery.

https://theangrygm.com/gaming-for-fun-part-1-eight-kinds-of-fun/

“I recently had a conversation with a few other GMs about discovery and exploration and the difference between expression and discovery. The two seem to get conflated sometimes. The theory runs that if the players find a new location, it is just as satisfying to ask them to describe what they find as to tell them what they find. But it isn’t. This conflates two different types of fun. Discovery seekers need the feeling that there was a secret waiting for them to stumble across and they found it. There is an element of conquest to it. If you ask them to make up their answer, you’re trading creative expression for discovery. And discovery-seekers will ultimately be unsatisfied.”

I wonder if the distinction you draw here between roleplaying and storytelling players also has to do with why some GMs seem unable to see beyond railroading. A lot of your advice on how to avoid railroading boils down to “roleplay the NPCs”: define who they are and what they want, then react to what the PCs do as the NPCs would.

So the kind of person who, as a PC, wants narrative control and storytelling mechanics is more likely to railroad as a GM, because he’s used to thinking in terms of narrative control and manipulation, not in terms of IC choices. And conversely, the kind of player who loathes storytelling systems is going to be less tempted to railroad as a GM because railroading gets in the way of what he wants. Just as, while a player, he wanted to describe his character’s actions and choices and discover the results, so now as a GM he wants to describe the world, be surprised by the PC’s actions, and then discover for himself what happens next.

I’ve seen players like that. (Who like narrative control mechanics because they like the feeling of control, which can translate to railroading when they GM.)

It’s far more common IME, however, for the appeal of a storytelling game to be a mechanical structure which enforces collaboration in narrative building. (This tends to be particularly true for people who have been railroaded by GMs in RPGs; storytelling games provide an escape from that.) These players rarely railroad as GMs (again, IME), instead generally fostering the type of narrative collaboration that they enjoy.

When I hear PbtA afficionados advocate this technique they typically suggest to provide a leading conclusion first, and then have the players support that.

I.e. “When you enter the appartment, you see clearly that it has been burgled. What do you see that makes you conclude that?”, and not the more open ended “You enter the appartment, what do you see?”.

Even though I am an immersion type of player, I don’t find the former that aggrevating. I think the reason for that is when the leading statement is provided, that immediately makes my mind conjure up images of the scene. Me just recounting those images doesn’t feel like authorial control to me, since someone else inspired them for me.

However, one of the things I love as a GM is to empower players to make conclusions for themselves. This teqnique undercuts that directly. Having the players describe a burgled appartment might feel ok enough, but it is a lot more fun to me to describe open drawers and stuff on the floor, and see the players (correctly) conclude that there’s been a burglary.

[…] Further reading: “Description-on-demand” […]