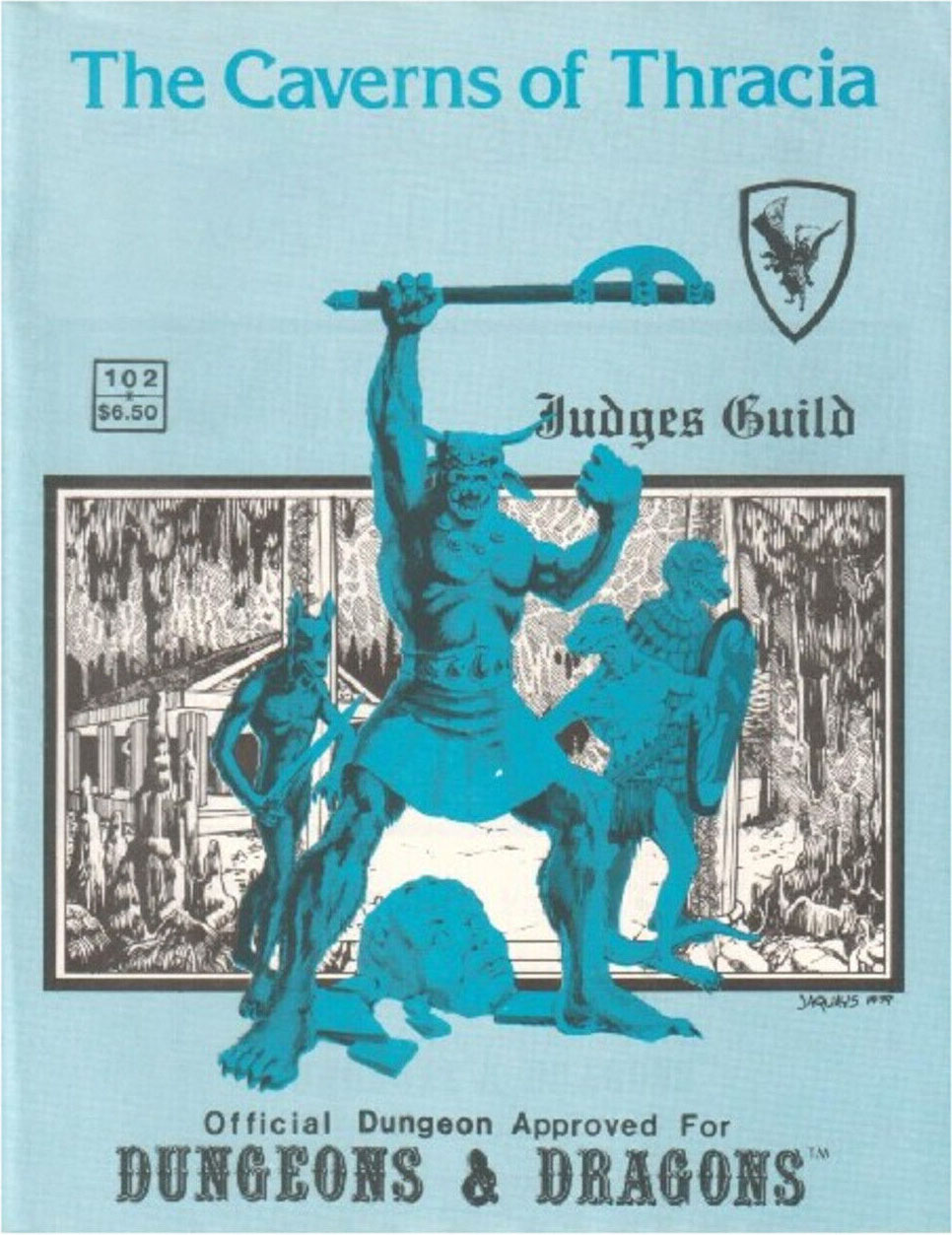

Christopher B. encouraged me in a post over at Grognardia to prioritize these session summaries of my Caverns of Thracia mini-campaign using OD&D. In Part 5 I wrapped up the end of the first session, which turned out to be such a success in the eyes of my players that several players asked for a follow-up.

Christopher B. encouraged me in a post over at Grognardia to prioritize these session summaries of my Caverns of Thracia mini-campaign using OD&D. In Part 5 I wrapped up the end of the first session, which turned out to be such a success in the eyes of my players that several players asked for a follow-up.

Ergo, session two.

For this session, the player roster was shuffled a bit: The player for Reeva couldn’t make it, but we added two new players. We glossed over the escape from the dungeon and moved everybody back to the logging village on the edge of the jungle containing the ruins.

Herbert the Elf had been rescued at the end of the last session and he volunteered to return to the complex to wreak vengeance (and loot treasure). He was joined by the core of the previous party (Thalmain, Trust, and Warrain), as well as new recruits in the form of Dominic and Thaxter.

Thaxter, it turned out, proved to be one of the two main highlights of the evening. Thaxter was an elderly gentleman who presented himself to the party as a worldly and experienced knight. The party was eager to have such an experienced swordarm as part of their expedition.

Unfortunately, Thaxter was nothing of the sort. It turned out that he was, in fact, the chef from the local inn. He’d seen the gold rush adventurers profiting left and right from the various ruins of the Thracian Empire and wanted in on the action.

The truth came out shortly after they had ventured back down into the dungeon complex: As they were crossing one of the rope bridges over the subterranean chasms, a giant bat swooped out of the darkness… Thaxter panicked and cowered like a little child, tossing his torch aside wildly and screaming in terror.

(The torch ended up landing on the rope bridge itself, and started burning one of the ropes. A couple of the players — realizing that they weren’t carrying any water — dropped their trousers and peed on the fire to put it out. This was not their noblest hour…)

In short, Thaxter — as a character concept — was brilliant, clever, funny, and memorable. When he eventually perished (after finally conquering his fear and bravely plugging a hole in the line when Trust was knocked unconscious in a fight against a band of lizardmen), he was applauded by the entire group.

Ironically, the players’ appreciation of Thaxter was not matched by Thaxter’s son — Quinton — who showed up shortly thereafter looking for his father. Quinton proved to be nothing but critical of his father’s (many) shortcomings, which led to this short exchange:

Thalmain: “Okay, look. We’re going to ask you a couple of, umm… hypothetical questions.”

Dominic: “Right. Hypothetical questions.”

Thalmain: “Hypothetically speaking, if you were suddenly faced by a giant bat, what would you do?”

Quinton: “… my father ran away like a little coward, didn’t he?”

Thalmain: “Umm… Yes. Uh… Hypothetically, anyway.”

(UN)FUN WITH MAPPING

For this OD&D mini-campaign, I’m not using any kind of battlemap. I’m also (a) strongly encouraging the players to keep a map and (b) requiring that, if they’re mapping, then their character is mapping. (In other words, they need to have pen and parchment; they need to be carrying them in their hands; and the map itself is a physical item.)

On the first level of the Caverns of Thracia there is a room that looks like this:

It looks easy enough. But attempting to communicate verbally what this room looks like proved to be really confusing. (And I had several opportunities, because the exact same issue came up again in the third session when somebody else was keeping the map.)

“There’s a platform jutting out over a chasm. Directly in front of you, on the far side of the platform, there is a semi-circular protrusion with an altar. Columns lead off to your right, ending in a stone bridge that leads towards a tunnel in the far wall of the chasm.”

At one point I even whipped out a small piece of paper and sketched the shape of the room. The map still got screwed up in ways that weren’t reasonable for characters actually standing in the room and looking at.

This reminded me why I eventually drifted away from this particular conceit in my regular campaigns. Having the characters keep a map can lead to a lot of fun gameplay: Analyzing the map for clues on where to explore next (or where some secret passage might be hidden). Losing the map. Getting lost due to poor mapping. Chewing up valuable time trying to make the map accurate. Using the map to re-orient yourself after getting forcefully lost.

But on the flip-side, the metagame complexity and pace dragging of trying to communicate any kind of non-standard passage or room shape can be incredibly frustrating. It also strongly encourages the design of relatively uniform floorplans (square rooms, straight corridors) to avoid the headache. But, of course, this uniformity ends up undermining the very type of gameplay that this type of mapping is supposed to enable.

I’m still not sure what the best solution is for this. Or if there is one.

Hanging around in the dungeon obviously isn’t conducive to a long or healthy life. (Not that this should come as any sort of surprise.)

Hanging around in the dungeon obviously isn’t conducive to a long or healthy life. (Not that this should come as any sort of surprise.)