Feng Shui 2 uses an action count (or tick-based) initiative: Characters make an initiative check using their Speed to determine the initial Shot Count that they’ll be taking action on. Each action is then rated by the number of “shots” it will take to resolve, and this shot cost is subtracted from the character’s current shot total to determine the Shot Count on which they’ll take their next action. When everyone’s Shot Counts hit 0, the current Sequence ends and a new Sequence begins with fresh initiative checks.

There are some mechanical advantages to this system: It allows for Dodges and other interrupt actions to be handled very fluidly (by simply applying a shot cost that adjusts when a character gets to take their next proactive action). The ability to easily handle actions that have different “weights” (whether from a dramatic or simulationist perspective) by assigning them different shot costs can also be very elegant (and Feng Shui 2 wisely leaves most of those distinctions up to the GM rather than miring the system with a bunch of arbitrary, predetermined values that would impede play through table look-ups).

For a long time, however, I personally found that the mechanical disadvantages of tick-based initiative systems significantly outweighed the mechanical advantages:

- The system encourages a methodology of calling out initiative numbers (“Okay, anybody going on 18? No? 17? No? 16. Yes, great.”) that I find clumsy and poorly paced.

- It requires more fiddly bookkeeping from everyone at the table, which can be a drag on pace.

- It tends to interfere with or prevent me from using advanced combat management techniques like on-boarding, prep rolls, and the like.

Basically, over the years I’ve come to the conclusion that combat is most interesting when you can keep things focused on the events happening in the game world – entering quickly into the conflict; fluidly moving and overlapping action resolution – rather than focusing on initiative values. Tick-based systems tend to inherently conflict with my ability to do that.

But as I got ready to start playtesting Feng Shui 2 scenarios this month, something clicked in my head. I don’t think it’s something intentional (at least, it’s never been discussed in a published Feng Shui book to my knowledge), but maybe I’m just dense and it’s taken me twenty years to figure out something that was immediately obvious to everyone else. (A quick survey of online discussion suggests otherwise.)

Couple common misconceptions I’ve seen floating around that you should toss out in case you’re harboring them:

- A Feng Shui sequence is not a “round.” If you try to think of it through the paradigm of the typical combat round found in D&D and other RPGs, you’re going to find it difficult to square the difference.

- The “shot” in “shot cost” does not refer to the time it takes to fire a bullet. It refers to a shot in a movie. (Although, appropriately for Feng Shui, the term shot was derived from the early hand-cranked cameras; you “shot” a film the same you “shot” a hand-cranked machine gun.) “Sequence” is the same thing: It’s a film editing term referring to a series of individual shots.

And the thing that clicked in my head is that you shouldn’t just treat these as appropriated terms that lend a filmic theme to Feng Shui’s mechanics; you should embrace them fully in framing and describing the action of your Feng Shui game.

FRAMING TO THE SEQUENCE

Start with the sequence: Mechanically, when the sequence ends, everyone rolls fresh initiative and a new sequence begins.

As the GM you should also key off this moment to dramatically change the fight. The first sequence should not just seamlessly transition into the second. Instead, the first sequence should definitively conclude and the first few shots of the second sequence should establish a new paradigm for the fight that makes it feel radically different from the previous sequence.

- Reinforcements arrive. (Fresh waves of mooks flood in. The Boss shows up and shouts, “What’s going on in here?!”)

- A chase sequence transitions from one environment to another. (After a bunch of tight-corners and narrow streets, the cars blaze up an entrance ramp and onto the freeway. The rooftop chase reaches the end of the warehouses and the cyber-apes jump down into the crowded stalls of an open-air market.)

- A chase ends and a set-piece fight begins. Or vice versa. (Neo stops to fight Agent Smith in the subway station. Agent Smith regenerates and Neo runs up the stairs and back into the city.)

- A major environmental effect begins or ends. (Artillery shells from a naval ship just offshore begin raining down on the battle. The abandoned building catches on fire. The scaffolding begins to collapse.)

- The bad guys unveil some new attack or ability that they were charging up, deploying, or otherwise holding in reserve.

When embraced, this structure will keep your fights fresh and interesting from beginning to end. Leaning into the sequence will naturally pace the fight in interesting ways.

If you have the right sort of group for it, encourage your players to get in on the act: The PCs can also be a driving force for “and now everything changes!” at the start of a new sequence. They can grab the heavy ordnance from the trunk of their car; or decide that it’s time to skedaddle with the McGuffin; or change tactics and start trying to blow out the support beams in the abandoned theater.

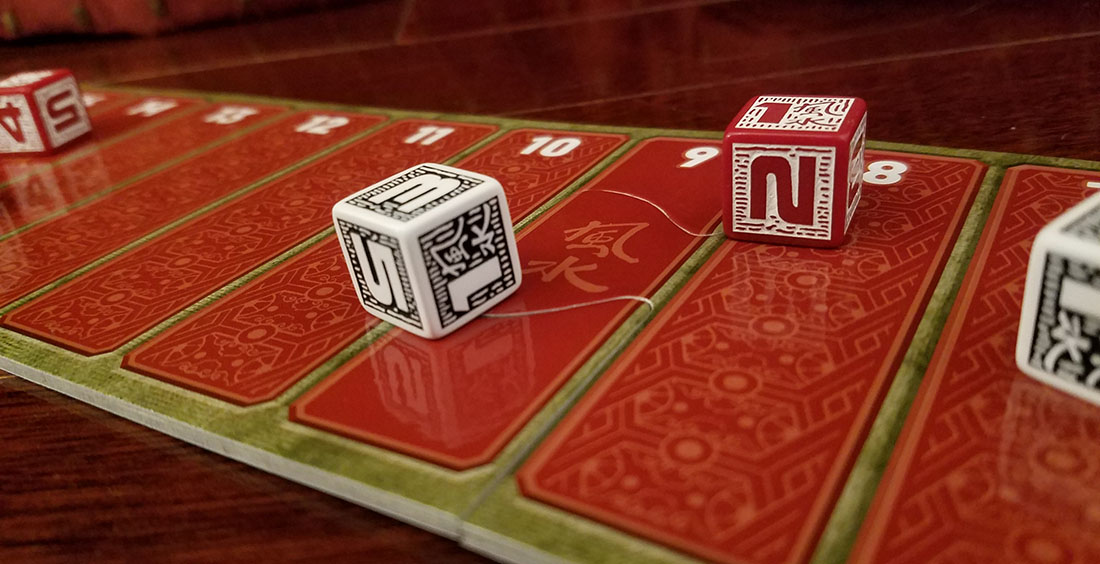

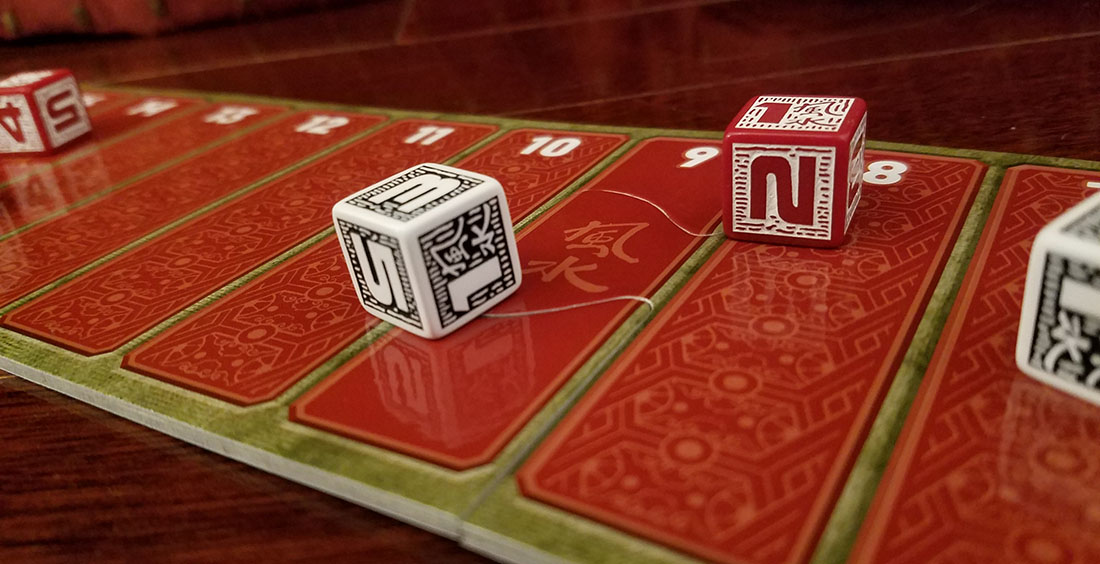

Feng Shui 2 includes a beautiful Shot Count tracker, and I recommend using it: With proper tokens, it will not only simplify the bookkeeping required by the system, it will also visually cue the entire table into both what’s currently happening and the “pace” of what’s coming down the pike. This will be particularly useful as we begin looking at shot-specific techniques.

FILLING THE EMPTY SHOT

It’s far from unusual for a Feng Shui sequence to feature shots in which no characters are taking actions. Instead of simply skipping over those empty shots, you should fill them with a content. In the same way that not every shot during a fight in an action movie focuses on the combatants punching each other, you can use these shots to widen the scope and depth of the scene.

This is a good time for establishing shots: Describe the train roaring past the train yard. It’s the submarine bursting up through the ice. It’s a cut to the nuclear missile that’s reached the apogee of its flight.

Taking a moment to focus on environmental effects is a good use of an establishing shot: The wrecking ball at the construction site reversing its pendulum swing through the air. The lava spewing into the air above the Godsforge. The gasoline spreading out from the car wreck.

Or you can feature the shot where that gasoline catches on fire. Dynamic effects, like that wrecking ball crashing through the scaffolding and forcing everyone fighting on the scaffolding to make a Defense check, can add great spice to a fight, but you should try to use then in limited quantities. (A little bit goes a long way here and you usually want to keep the focus on the characters fighting, not an environment that’s more volatile than a shack full of old dynamite.)

If you’re struggling to come up with a good establishing shot, take a peek at the list of Things That Can Happen During a Fight. You’re usually not doing them on the empty shot, but you can set them up. For example:

- Someone gets pushed through a neon sign. (Describe the dramatic aerial shot that swoops past the tall letters of the neon bulletin board atop the building.)

- Confused tourists stumble into the middle of the fight. (Establishing shot of the father gesturing at a map and angrily indicating which way they should be going.)

- Cut the counterweight on the castle gate to ride it up or down. (Establish the movement of the counterweight when the bad guys are closing the gate.)

- Someone’s sleeve gets caught in the factory machinery. (Describe a shot of the machinery, its mechanical pounding seeming to act like foley for the fists flying in the background.)

In John Woo’s seminal Hard-Boiled, there’s a classic establishing shot of a nursery at a hospital:

Gee… I wonder if anything’s going to happen in there when the guns come out? Nah. I’m sure it’ll be fine.

This creates a cycle of set-up and payoff which is both satisfying when you do it as the GM, but also effective at cueing the players with elements they can take advantage of at their own initiative.

Don’t feel like any of these moments need to be overwrought. Quick reaction shots are more than sufficient to punctuate the flow of the fight. Get in, establish one cool idea in a couple of sentences, and then move on to the next shot.

Empty shots can also be used for character moments – the types of interactions (witty dialogue, steely-eyed glares, the respite in which an exhausted hero catches their breath before plunging back into the melee) that elevate the best fight scenes. Such moments don’t require empty shots (they can be woven around and through the action in general), but an empty shot may give you an opportunity to particularly highlight such a moment.

This is also a great way to get the players involved: You may encounter a little difficulty where some players struggle to understand that these empty shot moments are not a “free action,” but if you can get them onboard you’ll be able to throw empty shots their way to set up cool character moments.

You can also blend multiple empty shots together into a single moment, but challenge yourself to resist that impulse and see what happens. If you have three empty shots in a row, try to find three distinct things to do with them, perhaps looking ahead to see who’s action is coming next and using those shots to ramp up to or shift the focus to that character’s situation.

SUBJECTS IN THE SHOT

At the opposite end of the spectrum, you’ll often have shots with multiple characters taking action. As described in the Feng Shui 2 rulebook, these actions are resolved:

- PCs first, in clockwise order from the GM.

- All GMCs in the shot.

Here, too, take a cue from what the shot system is telling you: These actions are all taking place in the same shot. In movie terms, that means they’re all happening on screen together. This does not necessarily mean simultaneously (shots extend over time), but it does mean that they’re all related to each other visually, spatially, and probably causally.

Generally speaking, the trick here is to mechanically resolve all of these intentions and only then weave the full description of what happens in the game world. This allows you to pull discrete mechanical interactions together in order to give the fight a wider scope and richer narrative flow.

Circumstances won’t always make this particularly easy and you may need to occasionally abandon ship, but I encourage you to challenge yourself: If the Shot Count is grouping together characters on completely opposite sides of the fight, is there a way that you can widen the shot? Or cause something happening over there to shoot across the fight and impact what’s happening over here?

DESCRIBING THE SHOT

Finally, embrace the filmic conventions of Feng Shui – the original love letter to Hong Kong action flicks – and lean into using actual shot terminology to describe your framing of the action.

One way of categorizing shots is by subject size (use the number of subjects appearing in the current shot as an easy guide for setting this, but break away from the obvious answer occasionally and see where that leads you):

- Extreme close-ups frame just one small part of the subject. (A single eye glaring; an entire fist filling the frame as it lashes out; a ghastly wound pouring blood down someone’s side.)

- Close-ups feature a single subject; the focus is on their facial expressions and the details of their emotions.

- Medium close-ups keep the focus on a single subject, but capture their head, chest, and arms. Surroundings are vague and unimportant.

- Medium shots can be focused on a single character, but can often capture several characters in the same shot (two-shots are common). One variation of the medium shot is the cowboy shot, used in Western films to frame subjects from the thigh-up in order to fit the character’s gun holsters into the shot.

- Medium long-shots are more likely to capture multiple subjects, and the environmental details became significant.

- Long shots or wide shots are used to either capture large groups of people and/or put the primary focus on the environment in which the characters find themselves.

- Extreme long shots or extreme wide shots feature characters (often multitudes of characters) who are dwarfed by the environment or the totality of the crowd. These will often be used for establishing shots.

You can generally just use close-up, medium, and long shots to convey most of the meaning you need verbally at a game table. This also makes for a good starter palette as you’re getting a feel for the technique.

You can also classify shots by camera position and movement: Eye level, low angle, dutch angle, over-the-shoulder, bird’s eye view, point of view, dolly shots (dolly in or dolly out), aerial, pans, tilts.

Also think about the quality of the shot: Handheld, steadycam, or a swooping crane shot can all convey different emotional connotations (even when evoked verbally).

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

Virtually all of these techniques can be implemented without the mechanical frame of the Feng Shui shot-and-sequence. But embracing that structure and pushing it hard will (a) give your Feng Shui fights a unique and distinctive flavor, and (b) serve as good practice for incorporating the best and most universal of these techniques into your other games.

Use the strong frame of the Feng Shui sequence to push you out of your comfort zone and, as I’ve suggested several times here, challenge yourself.

If you find yourself struggling, try this tip I presented in the very first Random GM Tips column here at the Alexandrian: Take a really great fight film – like Hard-Boiled or The Matrix or Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon – and narrate the action as it happens on screen, as if you were describing it to your gaming group. It sounds corny, but it builds your repertoire and helps loosen up your descriptive instincts. This is particularly effective for Feng Shui, because it will help you see fights through a filmic lens.

By the same token, don’t let yourself get fuddled by treating any of this as a straitjacket. For the first half dozen fights or so, lean into the structure hard and treat these as immutable “rules” so that you’ll force yourself to learn from the structure. But once you feel like you’ve mastered what the technique has to offer, be aware of when the structure needs to bend to the exigencies of what’s actually happening and what would be most effective. Push yourself to truly expand your horizons, but then remember that you learn the rules so that you know when to break them.