TRAIL OF DESTRUCTION (Alastor Guzman): Powerful fire elementals known as tlexolotls slumber deep beneath the surface of Tletepec. Above them rise volcanoes, their smoke and eruptions reflecting the uneasy dreams of the fiery gods below. Now Izel, one of the tlexolotls, has awoken and seeks to similarly awake his brethren, leading to massive volcanic eruptions and earthquakes which are racking the region.

This is a cool concept. Unfortunately, I find the adventure to be fairly baffling.

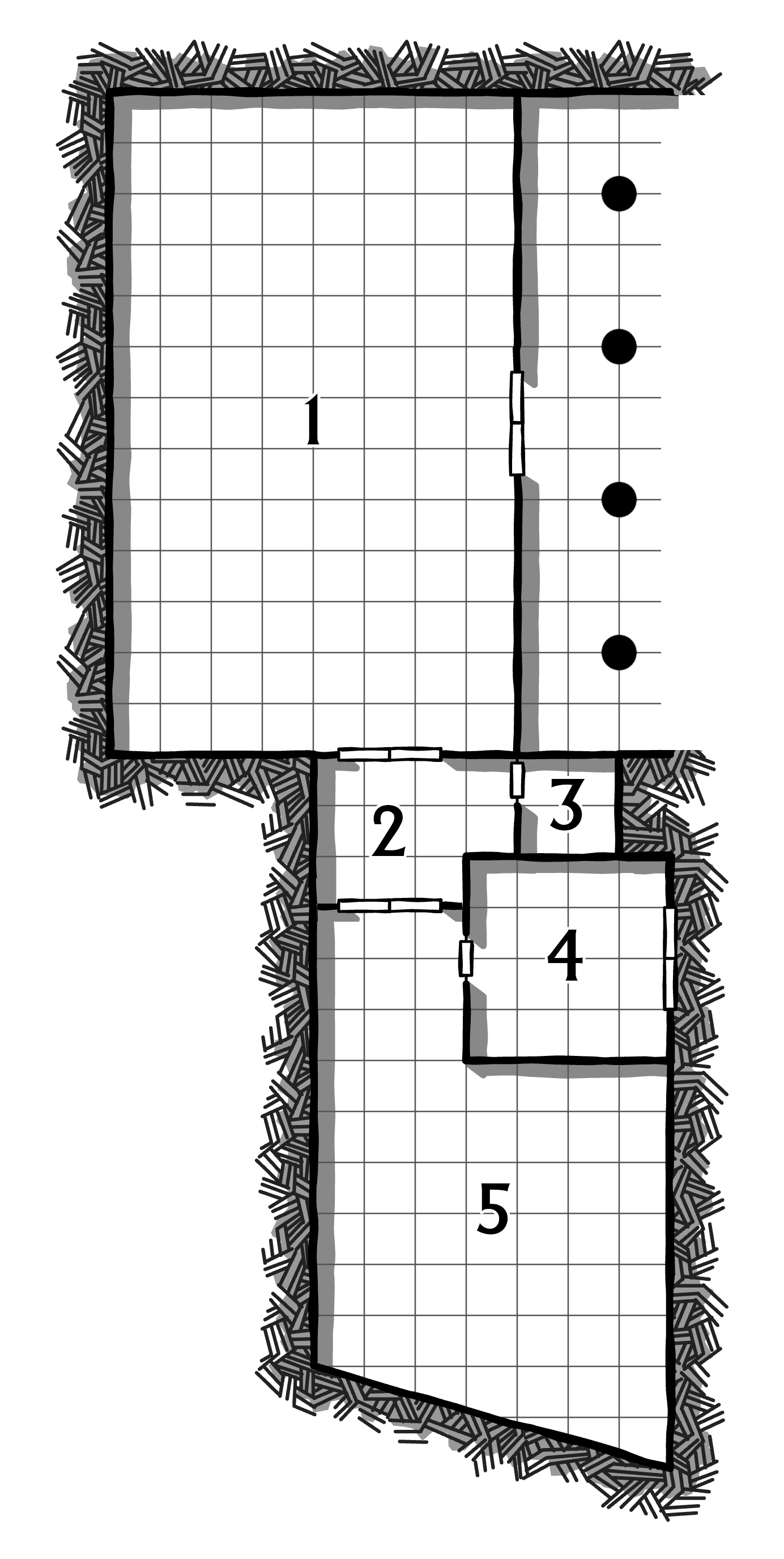

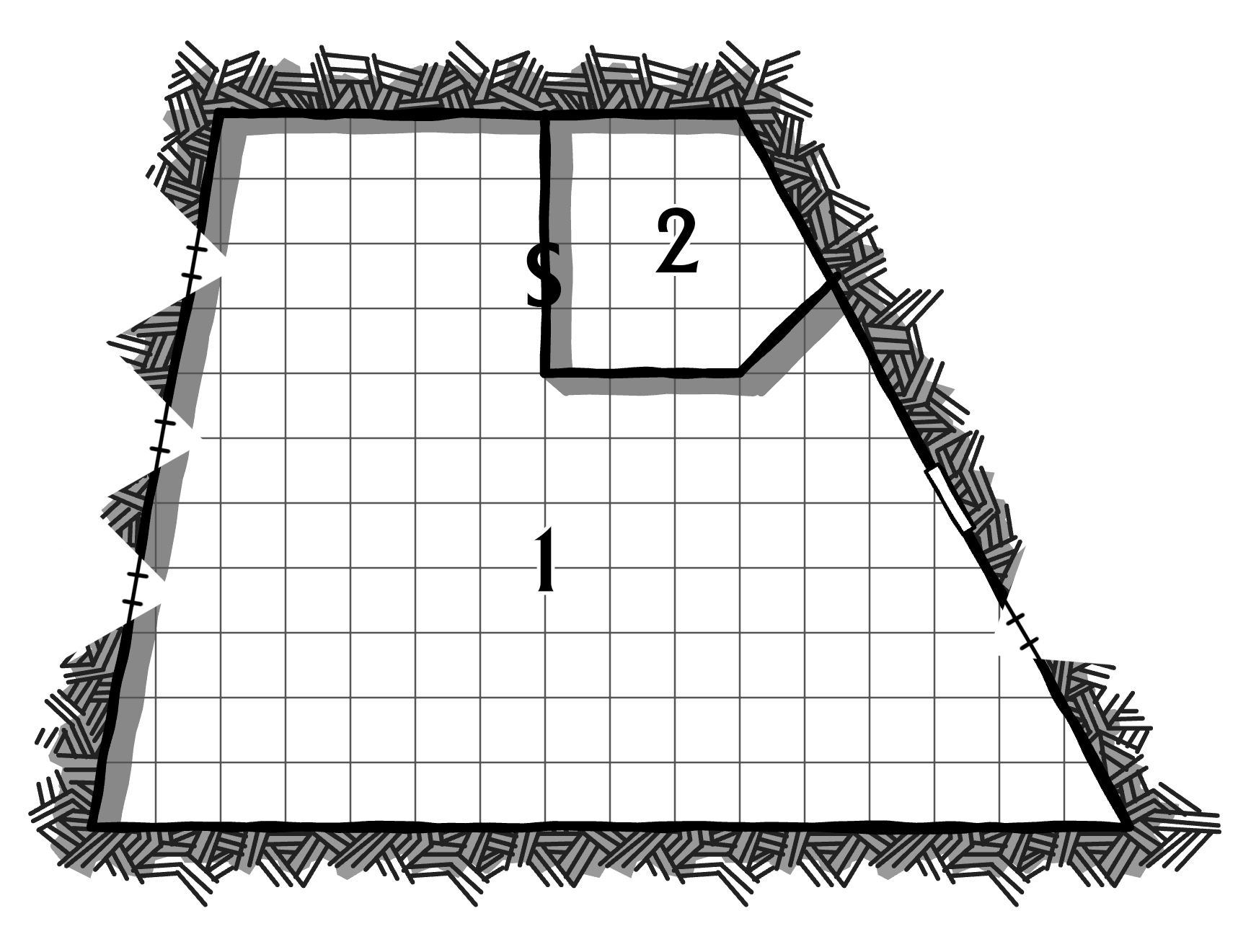

First, the adventure obviously revolves around erupting volcanoes. The PCs travel along ash-choked roads, crisscrossing the region alternately trying to figure out what’s happening and delivering offerings to the volcano gods. Given this concept, there are two things that would be super useful to include on the map: The roads and the names of the volcanoes.

On the actual map, unfortunately, there are no roads. (Oof.) Most of the volcanoes are also not labeled, although what appears to be a single volcano is labeled the “Onyx Volcanoes” (sic) and another set of volcanoes is labeled the “Twin Gods Volcanoes.” There are actually four volcanoes near this latter label, but I’m pretty sure I know which two were meant to be the Twin Gods. Also the “Twin Gods” are, as far as I can tell, never identified. It’s possible they’re supposed to be the “two lovers” mentioned in the Legends of Tletepec? But the lovers aren’t given names, either.

This ties into a general cosmological confusion which is the other major liability of the scenario: The tlexolotls are the volcanoes, but no one in the area believes that the tlexolotls actually exist. Instead, they believe that there are unnamed(?) gods inside each volcano. The local religion (or possibly multiple religions?) offers sacrifices to keep the gods placated, but the sacrifices are actually going to the tlexolotl and placating them instead.

This is a needless layer of confusion that doesn’t have any real impact on the scenario. There’s something potentially interesting about the PCs revealing that “your gods are actually not gods,” they’re just semi-mindless beasts who, if not kept fed, periodically “emerge in a rage, rampaging forth” to “gorge themselves on massive amounts of animal and plant life … until its belly is full,” except:

“emerge in a rage, rampaging forth” to “gorge themselves on massive amounts of animal and plant life … until its belly is full,” except:

- The consequences of this metaphysical nuclear bomb being dropped on the local culture is entirely ignored;

- the PCs figure out the truth by studying the prominently displayed carvings in all the shrines of the local religion (which is hilarious — “Yo! Your religion is wrong! The proof is all the bas reliefs you keep making!”); and

- even the “gorging beast” thing isn’t consistent, since Izel the main villain of the piece, is an awakened tlexolotl who explicitly doesn’t do that.

So it’s all kind of a big ol’ mess. This is also reflected in the central thru-line of the adventure, which is all over the place, but mostly revolves around the idea that Ameyali, a local religious(?) leader, is trying to deliver a shipment of offerings to the Gate of Illumination so that they can be given up to the gods and placate their fury. This is a problem, though, because Izel has dispatched his salamander minions to intercept the offerings and bring them to… the Gate of Illumination.

It feels like the adventure is missing a location (possibly due to word count?): Structurally it really needs the offerings to be going to Location X and then being redirected to the Gate of Illumination (where Izel is). There’s even a fire giant wandering around the area who will helpfully tell the PCs that:

Salamanders and fire snakes serve this tlexolotl. They have been stealing offerings meant for the gods and carrying them back to [the Gate of Illumination].

But instead the whole logical backbone of the adventure is broken.

There are some potentially big, interesting ideas here, but as written these are not coherently developed. Furthermore, it’s very hard for me to imagine running the adventure as written without it being a painful experience at the table.

Grade: D-

Prep Notes: The key to sorting this adventure out would be to clearly add the concept that every volcano in the region has its own shrine. (This concept is present in the adventure as written, it’s just completely obfuscated from the players.) The local cities are trying to send offerings to the shrines, but the salamanders and other servants of Izel keep intercepting them and taking them to the Gate of Illumination (the shrine at Jademount, which is the volcano formed around Izel).

(You could probably run with the idea that each shrine is referred to as a “Gate,” and create unique philosophical identities for each Gate.)

Having done this, there will still be some pretty drastic rehab required to beat the rest of the scenario into a coherent structure that will make sense to the players in any way other than “the NPCs told us to go there, so we went there.” But it would, I think, ultimately be salvageable.

IN THE MISTS OF MANIVARSHA (Mimi Mondal): Okay, good news! The festivals are back!

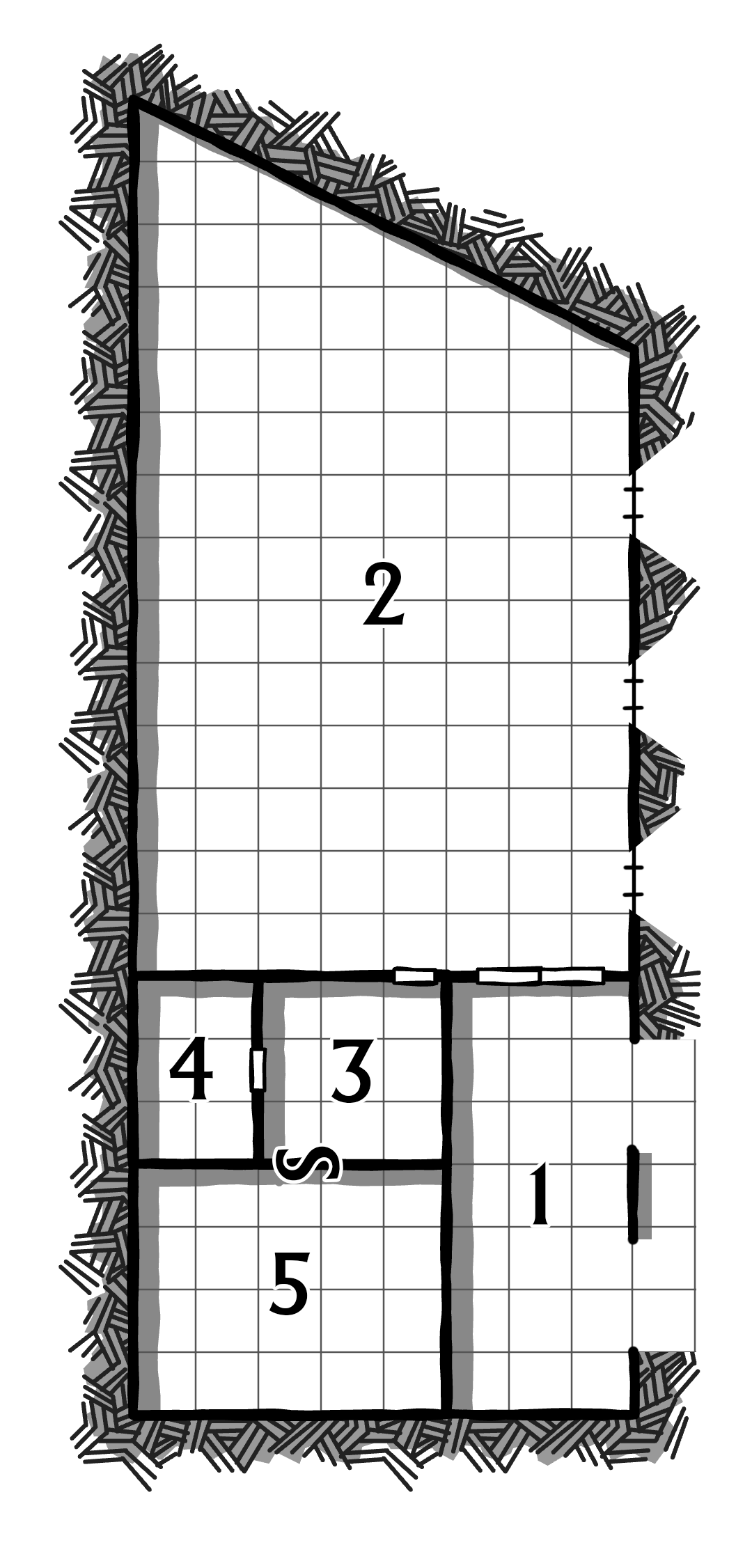

This time it’s the Shankha Trials, a vaguely defined athletics-and-art competition that dates back to the dawn of Shankhabhumi’s history. When the first human settlers arrived in Dishahara Bay, they discovered a land dominated by countless water spirits known as riverines. Each riverine is a guardian of a waterway, and the constant struggle for dominance among the riverines had turned this place into a hopeless maze of marshland.

The elven leader of the settlers, Kubjhatika, killed a giant mollusk and carved its shell into a beautiful work of art. She “offered it in tribute to the riverines, appealing to them for refuge amid the unforgiving lands,” and the “four greatest riverines — Adirohit, Iravati, Mehul, and Joltara – each wished to claim the Riverine’s Shankha.” Kubjhatika proposed the creation of the Shankha Trials to determine how the Riverine’s Shankha would circulate between the riverines. The riverines, in return, each raised up a large area of dry land where the people of Shankhabhumi could build their cities. These four cities became the major centers of civilization here, each supported by their patron riverine.

Five hundred years ago, however, catastrophe struck. At the conclusion of the Shankha Trials that year, a huge tidal wave swept down the Adirohit River and wiped out the city of Manivarsha. The riverine Adhirohit then vanished and its river dried up. The few surviving members of the Manivarshan people were scattered as refugees among the other three cities, but (apparently at least) remain a distinct cultural group in their diaspora and continue competing in the Shankha Trials.

The PCs are in attendance this year when an artist-athlete named Amanisha becomes the first Manivarshan to win the Shankha Trials since the catastrophe. The moment that happens, another tidal wave — considerably smaller — comes sweeping down the Iravati River. It simultaneously wreaks vast destruction, but also very specifically seeks out Amanisha and the Riverine’s Shankha and sweeps them upriver.

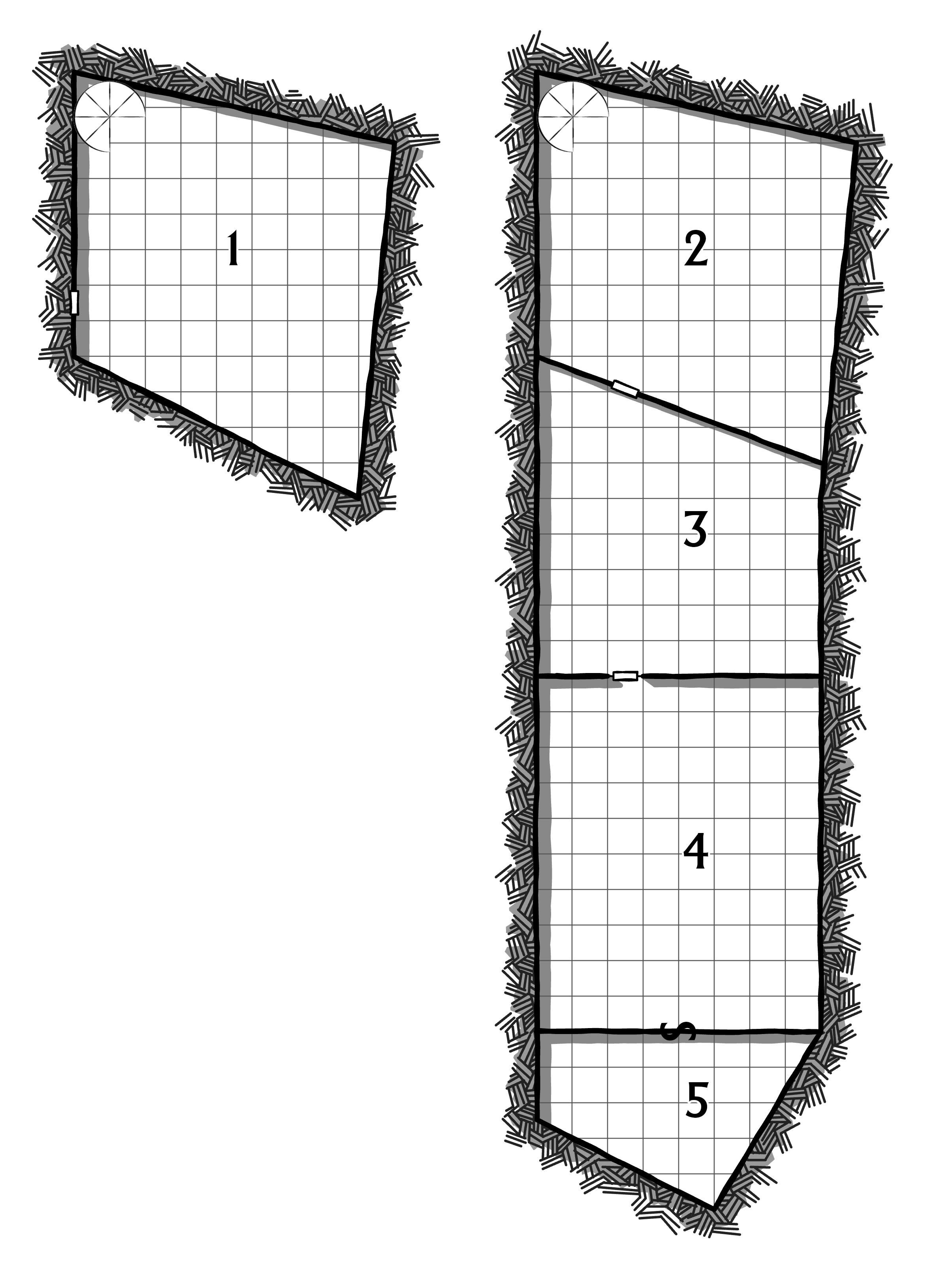

This whole concept, however, will naturally lead you to peruse the map of Shankhabhumi with a particular focus on the riverways. Then you’ll rub your eyes and look again. And then eventually you’ll give up because these rivers do not make sense. And that’s even before you get to the weird mismatches between map and text, like the Tinjhorna riverine who hopes to “one day be a mighty river,” but which, according to the map, is already the second longest river in the region.

(If you want a head canon, I recommend leaning into the fact that all these rivers are semi-sentient elemental gods and assume that they can just arbitrarily flow however they want to.)

The fact that the rivers don’t seem to make any sense is particularly unfortunate because the entire structure of the adventure is: Sail a boat upriver looking for where the tidal wave took Amanisha and the Riverine’s Shankha.

(Isn’t the Riverine’s Shankha like the most important political and religious artifact in their entire civilization? Yes. Does it seem likely that local leaders would mount an expedition to retrieve it? Yes. Are they going to do that? Absolutely not. They will send the PCs and nobody else. They will not pay for the PCs to rent a boat.)

Because the rivers don’t make any sense, the PCs can’t just sail upriver. Instead, they have to be supplied with a chain of NPCs who sequentially tell them where to go. That’s unfortunate, but ultimately this boils down to a sequence of river encounters, and these are mostly well done culminating in a conclusion that mostly makes sense if you don’t look at it too closely.

Grade: C

BETWEEN TANGLED ROOTS (Pam Punzalan): The shining star of “Between Tangled Roots” is the setting of Dayawlongon, a vast archipelago of islands linked by the awe-inspiring skybridges built in ages lost by the bakunawa dragons. That single, grand image captures the imagination.

The adventure begins with the PCs approaching the city of Kalapang when it’s attacked by a bakunawa which has been corrupted by evil spirits. The adventure confidently declares that “no matter what methods the characters use to reach Kalapang, the bakunawa has already departed by the time they reach town”… apparently forgetting that these are 10th level characters and it’s more than plausible that they could just dimension door straight into the attack.

Either way, the PCs are coming to Kalapang to meet with a binukot storyteller named Nimuel. In fact, they’ve been summoned by Nimuel so that she can introduce them to Lungtian, a dryad who was once friends with the bakunawa and believes its actions are due to its lair on the island of Lambakluha being corrupted.

This, of course, cues a road trip across the skybridges and then a journey across the haunted isle of Lambakluha. Along the way they’ll meet fellow travelers and, naturally, face uncanny dangers. When they reach the baknuawa’s lair, they’ll have the opportunity to either cleanse the corruption eating at the dragon’s heart or slay the dragon. Either way, the threat is ended.

“Between Tangled Roots” is just a rock solid adventure. The concept is simple, but has some nice thematic twists. The characters are varied and interesting to roleplay. The haunted isle is creepy.

Grade: B

Prep Notes: One thing to note is that the journey across Lambakluha requires rolling at least eight times on a random encounter table that only has five entries on it (and one of those including rolling again for another encounter). You should probably flesh that out a bit.