IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 32A: ENTHRALLED IN OLDTOWN

December 20th, 2008

The 18th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

When Tee returned shortly after noon, the group retrenched its plans. They had already decided to meet with Sir Kabel for dinner that evening and they now resolved to use that meeting to lay out a complete strategy for dealing with Rehobath, the arrival of Kirian Ylestos, the affairs of the Order of the Dawn, and the decisions facing Dominic.

This, however, left them with several hours of empty time to fill. Ranthir and Elestra had a variety of minor chores that they thought they might be able to pursue (the writing of magical scrolls, the gathering of information, and so forth), but then Tee proposed going to the project site of the cultists in Oldtown and laying siege to it.

This plan met with immediate and enthusiastic support. And, in short order, they found themselves approaching the building.

SCOUT BY SNAKE

Elestra called upon the Spirit of the City to cloak her companions from sight, allowing them to easily slip into the alley next to the building. Calling upon the Spirit once more, she shifted into the shape of a snake. Tee, using her boots of levitation, carried her up to the window on the second floor that she’d used before and slipped Elestra inside.

Slithering under doorways, Elestra noted several cocoons scattered around the upper level – some of them still whole, others hatched.

In a room on the far side of the building there were two of the hatched cocoons. There were also two doors, one of which had been barricaded shut with an assortment of half-broken furniture.

Elestra decided to avoid the barricade for now, and instead slithered under the other door. In the center of the next room were two of the “venom-shaped thralls”.

Fortunately, the creatures appeared to be sleeping – they were hunched down on the floor and their long, beclawed arms were drawn in close. Elestra beat a hasty retreat back into the outer room.

She considered heading directly back to the window where Tee was waiting. It would certainly be the safest thing to do. But, on the other hand, it would be helpful if she could finish scouting out the entirety of the second floor. Then they could form an accurate plan of action.

And so she slipped her way through the barricade and poked her head under the second door.

On the far side of the room there was a half-hatched cocoon. But extending from its broken shell there were writhing, gelatinous tentacles that groped grotesquely at the empty air. For a long moment, Elestra was captivated by the horrific sight of it. But then her reverie was broken by painful, stinging bites.

Wrenching her head out of the room, Elestra saw a swarming carpet of strangely deformed, red-and-black beetles pouring out of one of the hatched cocoons in the outer room. She had been literally overwhelmed by the outer edge of the swarm.

She fled back towards Tee with the chaos beetles biting and stinging her as she went. Tee, seeing her plight, flung open the window and fired once into the mass of creatures. The blast had little effect, but it did cause the creatures to fall back long enough for Elestra – momentarily freed from their mass – to escape out of the window as Tee scooped her up.

Ranthir, seeing the panicked scene above, reacted quickly. With a wave of his hand the window slammed shut.

Mere moments after the window shut, Tee saw one of the venom-shaped thralls scurry into view – evidently awoken by the sounds of the swarming chaos beetles. Before it had a chance to notice them hovering outside of the window, however, Tee dropped out of sight and returned to the alley below.

MELEE ON THE SECOND FLOOR

When they reached the ground, Elestra returned to human form. She quickly described what she had seen to the others. Since the second floor was so sparsely populated, they decided to quickly mop up the minimal opposition before the riled up chaos beetles alerted everything in the building to their presence.

Levitating back up, however, Tee found the window Ranthir had shut swarming with the chaos beetles – the entire surface a churning, chitinous mass. She blanched. Disgusting…

“Did we ever figure out why the bug-things were called venom-shaped thralls?” Elestra asked.

“Because they’re poisonous?” Tor ventured.

“But venom-shaped…” Dominic said.

“They’re made out of venom?” Elestra suggested.

Tee, meanwhile, was circling around to the western side of the building. There she found another window, this one looking out over the rear alley. Peeking through it she saw one of the thralls patrolling the hallway leading to the stairs. And there was another of the black cocoons attached to the far wall. But it would have to do. She eased her way up to the roof, tied off her rope, and lowered it to the others below.

Returning to the window, Tee eased it open and slipped inside. She slid in behind the banister of the stairs. From her hiding place there, she waited for Agnarr to reach the window. Then, once the patrolling thrall’s back was turned, she gave the signal: Agnarr leapt through the window, silently rolled to his feet directly behind the thrall, and then gave his familiar battlecry: FOR THE GLORY!

As the flaming greatsword bit deep into the creature’s chitinous hide, acidic ichor sprayed from the wound and oozed down its side. Agnarr’s arms burned at its touch.

The thrall whirled with a hideous, chittering hiss that echoed through the upper level of the ruined apartment complex. Tee, timing her move perfectly, circled it in the opposite direction and buried her sword in its back. It howled its hiss again, its serrated beak and claws going into a furious flurry at Agnarr’s expense.

Agnarr was forced back a step by the thing’s furious onslaught. “They’re bigger than we thought!” he shouted over his shoulder.

But then Tor, who had scrambled through the window behind them, stepped up and beheaded the creature with a single smooth stroke. Its head went bouncing down the length of the hall… but as it passed over the cocoon at the far end of the hall, a thrall-claw suddenly burst forth from the purplish-black mass and impaled it in mid-air.

“Oh shit…” Tee turned towards it and drew her dragon pistol. But as she prepared to fire, she saw – through one of the gaping holes in the wall – the chittering mass of the chaos swarm sweeping towards her like an ambulatory carpet. “Oh shit!” She swung her pistol in that direction and fired.

Her blasts had little effect, but then Ranthir stepped forward, lowered his hands, and bathed the creatures in flame. Unfortunately, they kept coming. Elestra, calling on her own magical might, dropped a ball of roiling fire into their midst, but the creatures swarmed around it and clambered up Ranthir’s legs – leaving hideous red welts in their wake.

Ranthir screamed. But then Elestra swung the ball of fire back into the midst of the swarm and, this time, the flames shattered the swarm’s hivemind, sending the desultory remnants scattering into the corners of the room.

Tor went racing past them and plunged his sword into the hatching cocoon – but to no avail. The half-dozen claws of the creature continued ripping their way to freedom.

Tee dropped her dragon pistol and drew her bow, wanting its greater accuracy. As the newborn thrall ripped its way free from the cocoon, Tee loosed her shot – placing the arrow straight through the emerging creature’s eye.

With a flip of her hand, Elestra engulfed the thrall’s head in a ball of the flame. And then Tee shot again, her arrow ripping through its second eye and bursting through the back of its skull – leaving a slightly flaming arrow flicker in the wall at the center of a splash of green ichor and black brain. The creature slumped forward over the edge of the cocoon.

Meanwhile, another of the thralls – the second of those Elestra had seen before – had burst through the door on the far side of the room. Agnarr moved to engage it and Ranthir quickly scurried in that direction. Laying his hand on the barbarian’s back, he released a sharp burst of arcane energy. Agnarr grew and grew and grew… finally reaching thirteen feet in height.

In a panic, the venom-shaped thrall scuttled backwards – its flashing claws and beak lashing Agnarr, but doing little real harm. Agnarr drove it back and then cut it in ichorous twain.

TIP-TOEING THROUGH THE TULIPS

Ranthir and Tee could both feel the venom of the chaos beetle swarm burning in their blood. As its effects grew worse, their limbs began to shake uncontrollably. Dominic was able to help Tee, but they lacked the proper resources to fully cure Ranthir (who was left shaking with a severe palsy).

Tor wanted to finish their sweep of the upper level as quickly as possible, convinced that anything on the lower level of the apartment building must already be aware of them. He moved into the next room, verified it was empty, and started heading towards the barricaded door.

But then, on the ceiling, he spotted an effervescent patch of violet-colored slime. It looked… unpleasant.

Since Agnarr was thirteen feet tall (and stooping even in the high, vaulted ceilings of these ruined apartments), Tor called him over to take a close look at the patch of slime – and deal with it if necessary.

But as Agnarr cut through the room at the center of the complex, the floor suddenly buckled beneath him – plunging him down to the first floor in a loud, splintering crash of broken wood.

Looking around, Agnarr saw the problem: Several support walls had been completely destroyed and there were several broken floor beams. He tried climbing back up to the second floor, but the acid-eaten floorboards broke beneath his weight a second time and dropped him back down again.

“I’m just going to stay down here,” Agnarr said, heading towards the far door of the room he’d fallen into. “Tip-toe… through the tulips…”

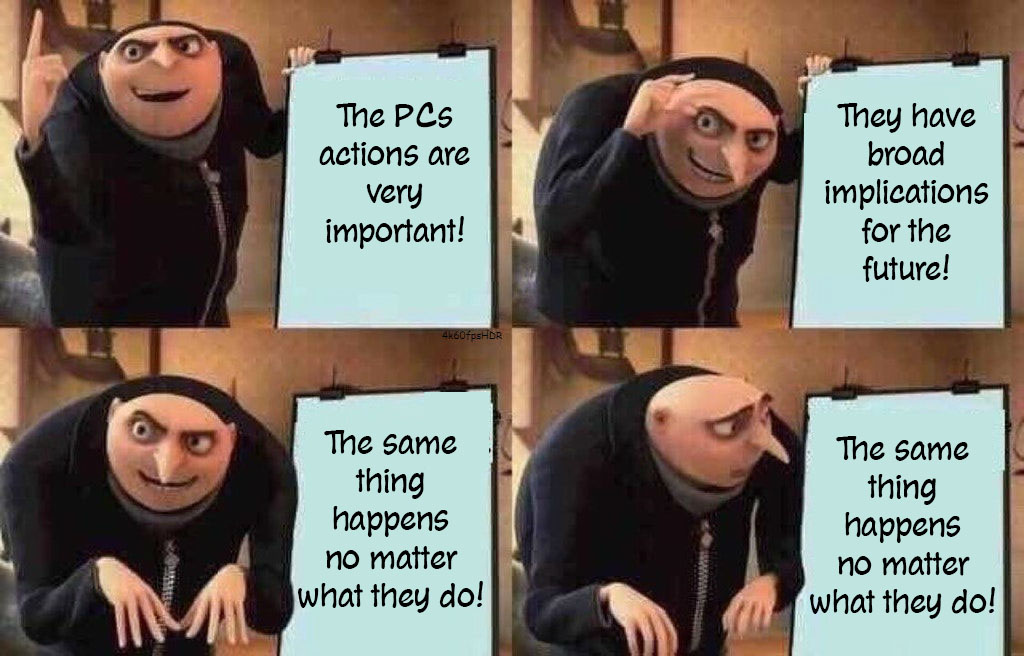

Running the Campaign: The Traps That Move You – Campaign Journal: Session 32B

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index