IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

IN THE SHADOW OF THE SPIRE

SESSION 31E: KABEL’S TALE

November 9th, 2008

The 18th Day of Kadal in the 790th Year of the Seyrunian Dynasty

A NOONTIME WITH KABEL

After dropping Iltumar back at the Bull and Bear (the lad was rather saddle sore), Tor returned to the Nibeck Street mansion. As arranged, Ranthir and Tee met him just inside the door. Tee broke the news of Kabel’s warrant (which she had learned from Elestra when she had returned earlier). Ranthir rendered him invisible and then headed out the door first, allowing Tor to slip out without any visible sign.

From the outside, Pythoness House still looked completely deserted. Tor passed through the gatehouse, easily slipping past two knights of the Order of the Dawn who were stationed as covert guards in the courtyard. He quickly found Sir Kabel and Sera Nara in one of the former bedchambers on the first floor, quietly discussing matters over a game of dragonscales.

Tor knocked on the door.

Sera Nara was jumpy. “Who’s there? Show yourself!”

“That will be… difficult,” Tor said. “It’s Tor. I thought it best if I came as secretly as possible.”

Sir Kabel waved Sera Nara down.

“Where should I sit?” Tor asked.

“Wherever you like,” Kabel said. “We are, after all, here at your sufferance.”

It took a few moments for the invisibility spell Ranthir had worked to wear off. As Tor became visible, Sir Kabel smiled, “It’s good to see you, Master Tor.”

“Before we begin,” Tor said, “I have a confession to make.” He quickly explained that he was responsible for Kabel nearly being captured. “I thought it was a snare. I am sorry.”

“No, the debt is entirely mine,” Kabel said. “Without the efforts of you and your friends, we would have all been captured.”

“I’m sorry to say that I have more bad news,” Tor said. “A warrant has been sworn out for your arrest.”

Kabel grimaced.

“I’d like to help you. We’d all like to help you. But first I’d like to know what happened that morning.”

A flash of anger crossed Sera Nara’s face. Sir Kabel held up a placating hand to her, “No. It’s all right. I’m sure that Rehobath has spread his story far and wide. It’s good to hear the truth.”

KABEL’S TALE

“I had taken several knights from the Order to train at the tournament field. Many of these were loyalists to the Church, but there were a few that were brought so that we might try to recruit them. We needed all the support we could if we were going to remove the False Novarch.

“Unfortunately, not all of those I trusted were truly loyal. Two of my knights – Aric and Thomas – attacked me. Crying their loyalty to Rehobath and with a vow to kill me for a traitor, they attempted to assassinate me.

“They failed, largely through the quick blade of Sera Nara. While we were still gathering our wits, another of my loyal knights rode up and warned us of further treachery: Sir Gemmell had attempted to gather those knights loyal to me and ambush them in the Great Hall of the Godskeep.

“We rode hard and discovered that Gemmell’s plan had failed. The loyalist knights had fought their way out of the Godskeep. But now there was heavy fighting on the green south of the keep and my men were pinned down between the Godskeep and the Cathedral.

“We were able to cut through the defensive line that Gemmell had formed. We fled west down Sunrise Street. When we came to the Street of a Million Gods, I ordered my men to scatter. The group I led eventually made our way to the pub in Rivergate and, from there – through your grace – to here.”

PRELUDE OF THE FATAR

“That explains many things,” Tor said.

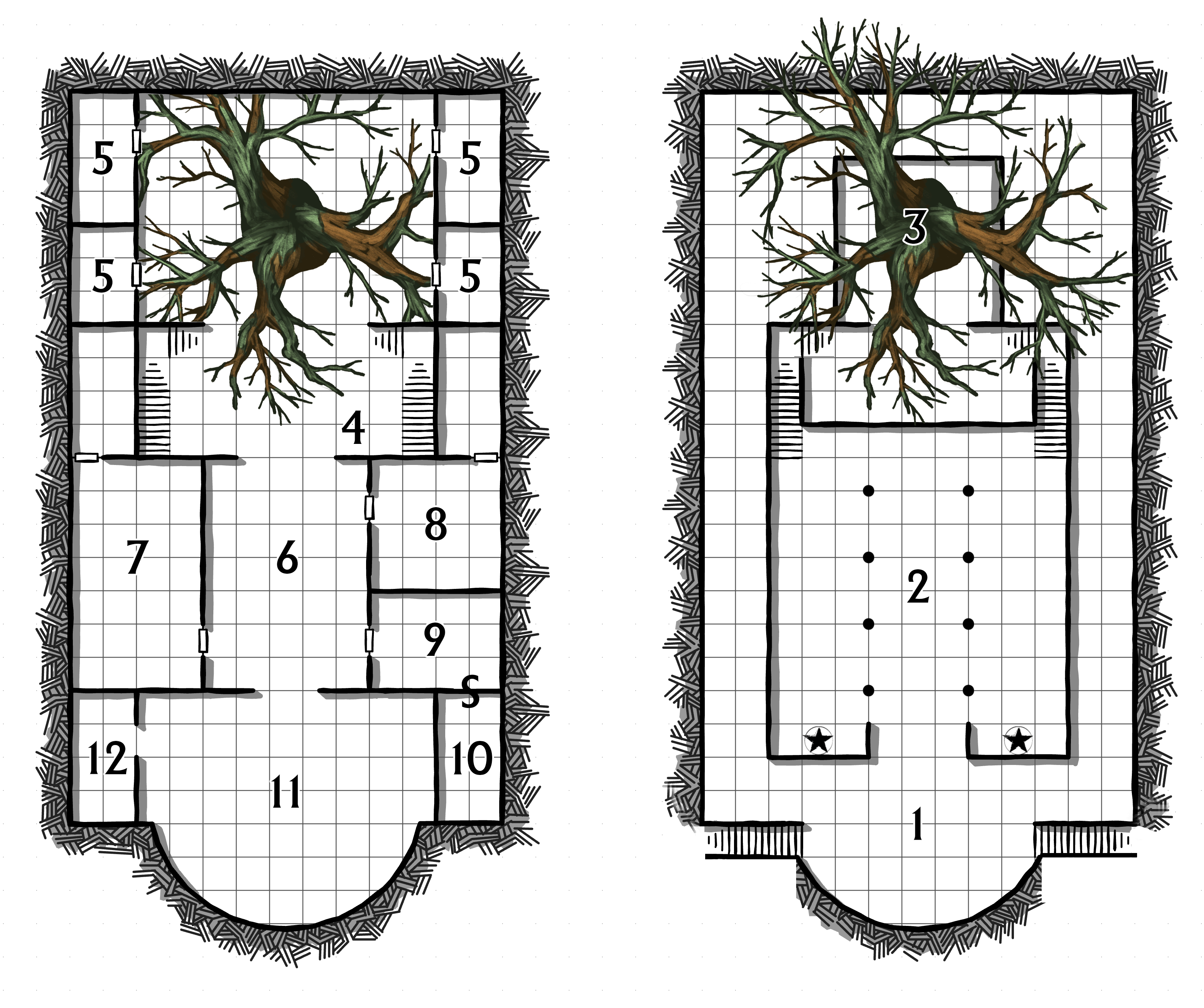

“Now, there’s something else I’d like to propose.” Sir Kabel leaned back and gestured expansively, taking in the whole of the room and beyond. “The knights loyal to our cause are scattered, hiding in bolt-holes around the city. They’re just waiting to bound by Gemmell and the other traitors and captured. But Pythoness House is practically a fortress. It could be secured against any assault by Rehobath or his cronies. You brought us here. Is it all right if use this as a safe haven for the others?”

Tor was hesitant. “I’m not sure I have the right to make the decision without first consulting my comrades. We’ve spoken, actually, of our need to find a place more secure – and secret – than the Ghostly Minstrel as a base of operations. We had been thinking of using Pythoness House ourselves.”

“I understand,” Kabel said.

“What are your plans, exactly?” Tor asked.

“I’ve received word from the Church in Seyrun. Kirian Ylestos has been raised as the Silver Fatar of Athor and dispatched to Ptolus to take control of the Cathedral. He’s bringing with him a small platoon of the Crimson Guard. With the guard reinforcing my loyalists, I believe that we’ll able to overwhelm Sir Gemmell, capture Rehobath, and put an end to this farce.”

“How many men do you have?”

“Twenty or so loyalists, unless more have been captured,” Kabel said. “And the platoon will bring another twenty armed men to our side.”

“And how many men does Gemmell have?”

“At least forty knights still serve him in the Godskeep,” Kabel admitted. “But when the true Fatar arrives and the word of the Church is heard again, I think many of them will realize their folly. Of course it would be easier if… Since he isn’t here, am I to understand that Dominic is not to be trusted?”

“No,” Tor said. “I only came alone in an effort to be as secure as possible.”

“If Dominic were to publicly denounce Rehobath, that would go far towards discrediting Rehobath’s heresies. More of the Order might turn against him and Gemmell.”

“He’s not a friend to Rehobath, I can tell you that,” Tor said. “But beyond that I can’t say. I would need to ask him. Perhaps it would be best if I brought all of my friends here to meet with you.”

Tee stepped out of the shadows by the door. “Some of us are here already.”

TEE’S PATH

After Tor left the Nibeck Street mansion, Tee had waited ten minutes and then climbed over the rear wall of the mansion. When she had reached Pythoness House she hadn’t bothered trying to go through the gates, instead climbing the wall and quickly reaching the roof above the gatehouse. From there she was able to look down into the courtyard and easily spotted the two knights guarding the entrance. She had slipped down through the gatehouse (saying a quiet “hello” to Taunell) and started looking for Tor. It took her several minutes, but she had arrived outside the door just in time to hear the last few sentences of the conversation.

Nara leapt to her feet and her sword leapt into her hand. “Who are you?”

Tor quickly made the requisite introductions. Tee gently pushed Nara’s sword away from her throat as Kabel waved her down again.

“Apparently we’re going to need new guards.” Kabel smiled.

They agreed to meet for dinner that evening and Tor asked him if they would need any supplies or the like.

“No. Nara is quite… skilled in keeping a low profile,” Kabel said. “She should be able to supply all of our needs. I look forward to our… palaver.” He smiled again. “Master Tor, I am forever in your debt.”

“It was the least I could do,” Tor said.

Kabel led them out into the courtyard – quite confusing the two guards who were still standing duty there (Kabel promised to explain things to them later). Then they made their farewells and left.

BACK AT THE MANSION AGAIN

Returning to the Nibeck Street mansion, Tee and Tor met up with the others and filled them in on the situation. They all readily agreed to return to Pythoness House for dinner the next day and listen to Kabel’s proposals.

Tee, having business in the city, left the rest of them to return to their vigil in the Banewarrens. On the walk back towards the excavated cave, the discussion turned towards what Dominic should do: Denounce Rehobath or continue keeping as low a profile as possible?

“So what is Vehthyl telling you to do?” Elestra asked.

“Vehthyl has nothing to say about it,” Dominic quipped.

“What about that other saint?” Elestra said.

Dominic was getting uncomfortable with her cavalier attitude towards the whole matter. He still wasn’t sure what he thought about being a saint or the “Chosen of Vehthyl” or whatever, so he wasn’t prepared for her to be so familiar with the idea of it. “Do you mean the Star of Itor?”

“Yeah. What was it he said to you? That you should follow your heart? What is your heart saying?”

“I… I don’t think I know,” Dominic said.

“I guess it’s a question of where your loyalties lie,” Ranthir said.

“I don’t know that, either,” Dominic said.

“We may not know which side is right,” Tor said. “But I think we know which side is wrong.”

Running the Campaign: Gore-Spattered Reactions – Campaign Journal: Session 32A

In the Shadow of the Spire: Index