BUSINESS OF THE VLADAAM SLAVE WAREHOUSE

This collection of posted bills records recent sales and transfers of inventory through the lower warehouse. A sampling of entries include items such as:

- Elven maid, 78 years of age, permanently dominated to any compliance

- Four dwarf workers, dim-witted but strong in thew

- Female child, of island stock

- Boy of sixteen, tongue removed, docile

Most of these slaves are being shipped to an “Ennin slave market” which is apparently located in the Undercity “beneath Delver’s Square” (the slaves are being transported via the sewers). Slaves are also being shipped to three “curse dens” located around the city:

- Curse Den – Guildsman District – Nethar Street

- Curse Den – Oldtown – Yarrow Street

- Curse Den – Rivergate – Outer Ring Row

In addition to slaves, large shipments of something referred to as “liquid pain” are also being shipped to the curse dens from here.

One particular reference of note identifies a batch of slaves as being “held at the behest of the Pactlords”. Another says that a slave is to be sent “directly to Tridam Island by command of the Pactlord”.

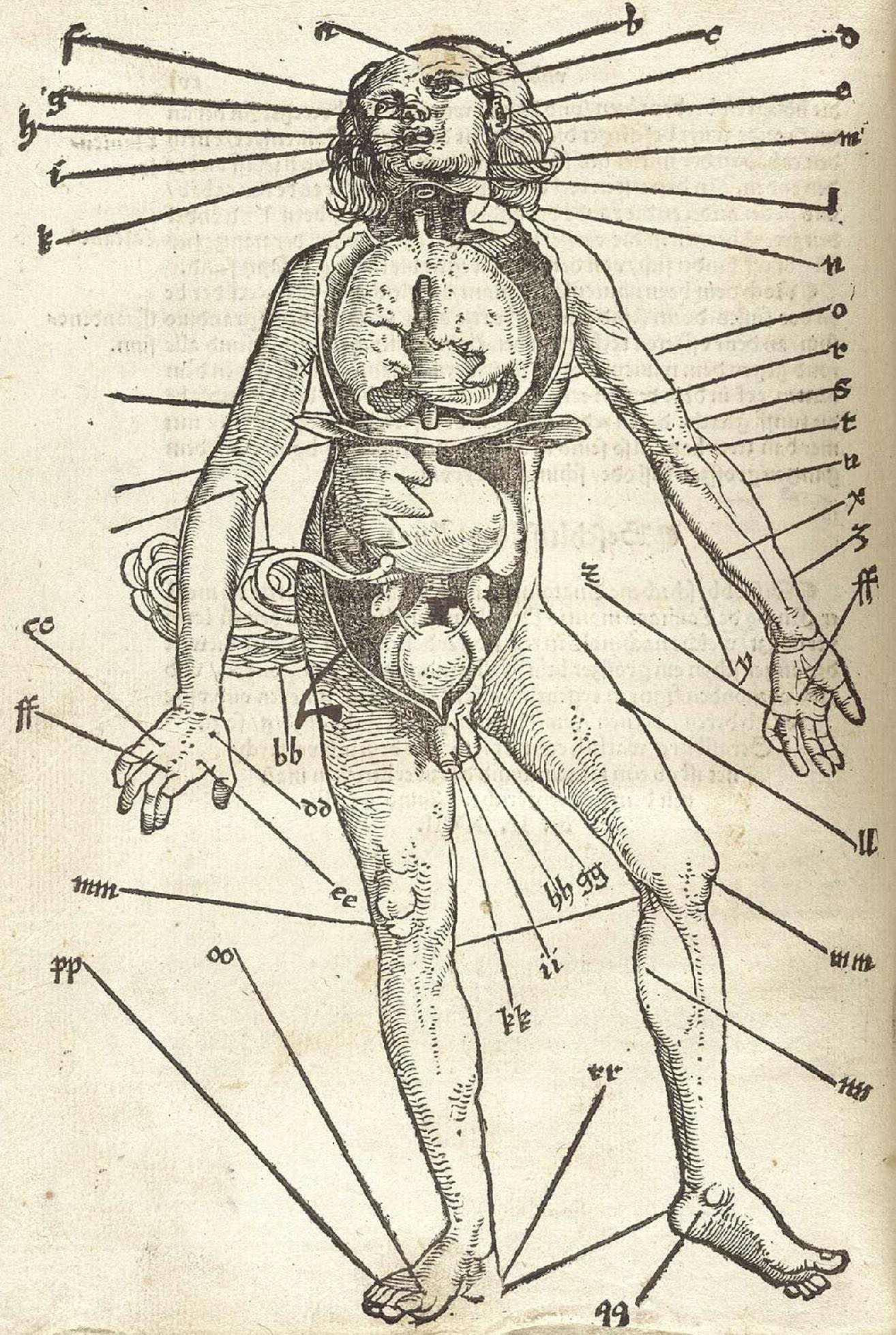

INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE APPARATUS OF LIQUID PAIN

Detailed anatomical diagrams and accompanying texts explicate the points on the human body to which various tubes, syringes, and metallic attachments are to be placed (while others are stimulated through the use of acupuncture needles, including several needles placed into the optic nerves). The goal is to create “overlapping resonances of agony”, serving as the raw catalyst for withdrawing a substance referred to as “liquid pain” or “agony”.

The full process requires the use of a complicated apparatus capable of generating a “sympathetic resonance” which can be contained within glass cylinders crafted with exact precision.

In addition, the properties of the resulting “liquid pain” are detailed, along with alchemical instructions for how it can be purified and “stabilized”.

AGONY: Also known as “liquid pain”, this thick, reddish liquid is the distilled essence of pain, captured using special spells or items. It is highly sought after by outsiders. Through an alchemical law of antagonism it creates a feeling of intense pleasure in addition to its other effects. Recreational users use small, ceremonial knives to cut themselves and deliver the drug.

A MISSIVE REGARDING SLAVES

Guildmaster Arzan tells me you have a sharp eye. I expect you to practice it now. We are conducting crucial experiments in the apartments on Crossing Street and are in need of experimental stock. We are particularly in need of those with an affinity for metamorphic compounds while also possessing the physical endurance to withstand the experimental techniques. If you observe any such during your service, flag them to my attention immediately.

LETTER TO GUILDMASTER ARZAN

To Arzan, the most illustrious Guildmaster of the Red Company of Magi—

I have recently had an item of most potent power pass into my possession.

While slipping through the Teeth of Light after sailing north towards Trollone, we were blown off course by a strange tempest of silver and black which first seemed to roil the waters beneath us before emerging – or, perhaps more accurately, whipping forth – in what could only be described as a violent evaporation.

I was not certain that the Sarathyn’s Sail would survive the strange gales which ensued, nor the strange manifestations which occurred therein. As for those of my crew who simply vanished during the storm… I pray that they were merely swept into the sea and met their fates in a watery grave, for the alternative is too disturbing to contemplate.

When the storm finally released us from its grasp, we were in ill condition. Fortunately, we found ourselves near a small island with a hospitable cove. We were able to limp our way into this and begin effecting repairs.

While these efforts were under way, I led a small band of men into the island’s interior in search of a fresh water well or spring from which we could resupply. Instead, we stumbled upon a set of cyclopean ruins. These were marked by a great number of carvings, bas reliefs, and statues depicting serpents and, within the deeper recesses of the complex, serpent-headed men.

With dusk closing about us, we returned to the ship, but I vowed to return the next day and continue our explorations. It was at this juncture that the first of my men disappeared. At the time we thought it simply misadventure, but subsequent events would prove this not to be the case.

Returning to the ruins the next day, however, we pushed further into the lower chambers. Within one of these chambers I discovered, among other treasures, a curious ring in the the shape of twin serpents, one of mithril and other of taurum, swallowing each others’ tails. We have been able to ascertain that not only is the ring itself magical, but that it has been constructed to contain some even greater magical enchantment. It is for this reason that I am sending it into your care, in the hopes that perhaps your Red Magi might be able to unlock its secrets.

As for the ruins themselves, it emerged that the serpent-men who had constructed them had not entirely abandoned them. Instead, they appear to have withdrawn into caverns even deeper beneath the island. I suspect that they return to the upper caverns only as a kind of holy pilgrimage. As for what other secrets or lost lore they might be concealing, or what cataclysm precipitated their withdrawal from the sunlit world, I can only speculate.

Yours sincerely,

Captain Crotika

LETTER FROM THE FOUNDER’S GUILD TO CAPTAIN MORSUL

Captain Morsul—

Please accept this hellsbreath rifle, so recently liberated from the Shuul, as a token of good faith from the Founder’s Guild.

You will find it to be a powerful and potent weapon, but extremely dangerous if carelessly used. When priming the gunpowder pump, great care must be taken not to over-pressurize the reservoir of alchemist’s fire. If the reservoir becomes over-pressurized there is a great risk of a back-blast being triggered which can destroy the weapon entirely (and cause great harm to the one wielding it).

Similar caution should also be used when refilling the reservoir, as there can be great risk in the moments during which the alchemist’s fire is exposed to raw air.

Master Astrek

Red Company of Founders

Brass Street