Lesser bloodwights are either the pupa-like clone-spawn of true bloodwights or the first stage of recovery for a bloodwight who has been reduced to a desiccated state.

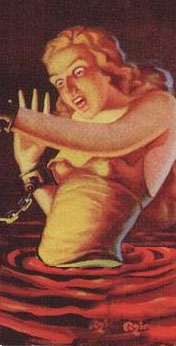

The Crimson Sheen. The signature of the bloodwights is the sheen of blood which they cause to erupt on the skin of the living. They are so inimical to life, that mortal flesh erupts in a hemorrhagic rejection of their presence. But the bloodwight itself thirsts for the warmth and energy of life, their limbs growing sleek and supple in its presence.

The sheen notably does not require line of sight, allowing bloodwights to lurk in sealed up attics or glide through city sewers. There are tyrants who have been known to wall up lesser bloodwights in oubliettes, into which can be thrown doomed prisoners.

Blood-Damned Nests. Bloodwights have a strong nesting influence, constructing mounds from whatever material may be at hand (furniture in mortal dwellings, detritus in ruins, leaves or fallen trees in forests, and so forth).

There may be a hunting component to this behavior, as the bloodwights can lay hidden within a nest while nevertheless feasting on any living creatures who pass by. In some cases, those excavating these nests have found them to be connected to other nests in the same area through shallow tunnels.

BLOODWIGHT, LESSER

Medium undead, neutral evil

Armor Class 14

Hit Points 45 (6d8+18)

Speed 30 ft.

STR 14 (+2), DEX 12 (+1), CON 16 (+3), INT 11 (+0), WIS 13 (+1), CHA 16 (+3)

Skills Stealth +3, Perception +3

Damage Resistances cold, necrotic; bludgeoning, piercing, and slashing from nonmagical weapons

Damage Immunities poison

Senses darkvision 60 ft., passive Perception 13

Languages Any

Challenge 3 (700 XP)

Proficiency Bonus +2

Bloodsheen. A living creature within 30 feet of a lesser bloodwight must succeed at a DC 14 Constitution saving throw or begin sweating blood (covering their skin in a sheen of blood). Characters affected by bloodsheen suffer 1d4 points of damage, plus 1 point of damage for each bloodwight within 30 feet. A character is only affected by bloodsheen once per round, regardless of how many bloodwights are present.

Health Soak. A lesser bloodwight within 30 feet of a living creature gains 2 hit points per round. A lesser bloodwight benefiting from health soak will gain hit points even after their normal maximum number of hit points has been reached, up to a maximum of 66 (the maximum number of hit points possible per Hit Die).

ACTIONS

Multiattack. Lesser bloodwights make two claw attacks.

Claw. Melee Weapon Attack: +4 to hit, reach 5 ft., one target. Hit: 9 (2d6+2) bludgeoning damage.

Blood Welt. When a creature is struck by a lesser bloodwight’s claw attack, they must succeed at a DC 14 Constitution saving throw or suffer a blood welt. A blood welt bleeds for 1 point of necrotic damage per round. The victim can repeat the saving throw at the beginning of each turn, ending the effect of all current blood welts on a successful save. Alternatively, the bleeding can be stopped with a DC 14 Wisdom (Medicine) check.

Bloodwights appear in The Complex of Zombies.