As a first step in experimenting with urbancrawl structures, I simply broke down the three basic elements of ‘crawl-based play and tried to apply them to an urban environment:

- Keyed Locations

- Geographic Movement

- Exploration-Based Default Goal

KEYED LOCATIONS

What are we keying? Neighborhood? Buildings? Organizations? People?

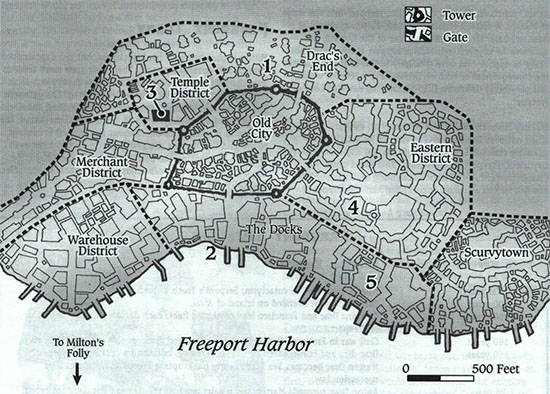

Neighborhoods seem too large. For example, here’s a map of Green Ronin’s Freeport as found in the Death in Freeport module:

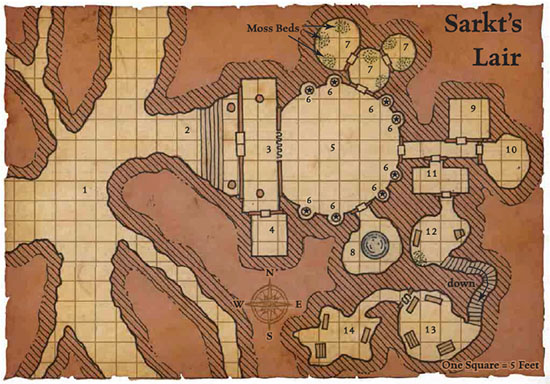

If you look at something like the Temple District, it’s pretty easy to imagine multiple locations that the PCs would want to interact with. If you’re trying to key multiple entries to a single location, it’s a dead giveaway that you’re keying at the wrong scale. For example, the idea of writing up multiple key entries for a single dungeon room probably sounds inherently weird to you. Although, just for the sake of argument, here’s an example from Lords of Madness I recently stumbled across:

Hexcrawls tend to be a little more forgiving of multiple keys per location, but even there I would argue that if you’re frequently keying lots of stuff into a single hex it’s an indication that your hex map is at the wrong scale.

Individual buildings, on the other hand, seem too small. Even a small city like Freeport has hundreds or possibly thousands of buildings. Keying even 10% of them would be a daunting task, and if you left 90% of a dungeon or a hexcrawl unkeyed you wouldn’t have enough material to hold the scenario together. (And even if you did key them, most of them would be boring. It would be like keying every tree in a forest for a hexcrawl.)

Keying organizations or people would give you a very different way of “navigating” the city. For example, Monsters & Manuals talks about building a relationship hexmap for urban-based sandboxes.

But since our next bullet point is geographic movement, I’m going to at least temporarily steer away from that and propose that we should be looking to key a geographic entity somewhere between neighborhoods and individual buildings.

GEOGRAPHIC MOVEMENT

How do we move through a city?

It seems like the obvious question to ask here, but I find that it ends up being a trap. If you’re like me, when you go out “into the city” you’re generally pursuing some specific goal: You’re going to the grocery store. Or driving to Suzie’s house. Or walking to the park.

I’ve come to think of this as “utility-based” or “target-based” movement. It’s the way I’ve run movement in an urban environments at the game table for years: The PCs say they want to go to Castle Shard and, at most, I figure out how long it takes for them to get there before segueing directly to, “You arrive at Castle Shard.” (Occasionally there might be an encounter along the way that gets triggered one way or another.)

But target-based movement is anathema to the ‘crawl structure. The PCs aren’t making a choice of geographic movement, they’re making a choice of where they want to be.

The distinction might be clearer if I apply the same logic to wilderness travel: Let’s say the PCs are in City A and they say, “I want to be in City B.” You can resolve that by looking at a road map, calculating how long it will take them to travel along the road, and then say, “Three days later you arrive in City B.”

But if you do that, you are not hexcrawling.

Which is not to say that there’s anything wrong with that. There are plenty of situations where that is exactly the right way to resolve that sequence of events. But it’s not a ‘crawl.

Similarly, if my players say, “I want to go to Castle Shard.” And I respond by saying, “Five minutes later, you arrive to find the drawbridge lowered and Kadmus waiting to greet you outside.” There’s nothing wrong with that. But we aren’t urbancrawling.

EXPLORATION-BASED GOAL

The key distinction here appears to be the difference between travel and exploration. Which neatly brings us to our third bullet point: A default goal based around exploration.

What does it mean to explore a city? Does it mean anything at all? How are we interacting with the city when we’re “exploring” it?

If you google “explore a city”, what you generally find is a lot of travel advice. And most travel advice takes the form of target-based movement (“take a tour”, “go to a museum”, “visit a club”, etc.). Alternatively, we have this guy who explored a city by flipping a coin at every intersection to determine his route. And here’s a blog post talking about women walking through New York on foot, but they’re doing so just for the experience.

This may be an insurmountable hurdle. If “exploring a city” doesn’t actually mean anything – if it’s not a naturalistic behavior that characters would actually pursue – then we’re trying to model something that doesn’t exist.

But let’s not despair quite yet. Let’s tackle this from a different angle: What’s the goal we’re trying to pursue in the city?

For example, in the dungeon we’re looking for monsters to slay and treasure to loot. In a dungeoncrawl this naturally carries us from room to room looking for the room which contains these things. Similarly, in the hexcrawl we go from hex to hex seeking locations filled with interest.

So if you’re a fantasy adventurer who has just walked through the gates of a city… what are you looking for?