By 1982, urban RPG supplements had pretty much universally transitioned to become narrative-backdrop travel guides: The modern gazetteer format that generally features a history of the city, a description of notable locations, and a cast of important NPCs. (Vestigial rumor tables hung around here and there for a few more years, but generally faded away until the OSR began bringing them back into vogue.)

faded away until the OSR began bringing them back into vogue.)

Which is not, of course, to say that there aren’t some truly fantastic city supplements. I actually ended up surveying a lot of great stuff while researching these posts: The City of Greyhawk boxed set, the truly prodigious combination of FR1 Waterdeep and the North with the Forgotten Realms: City System Boxed Set, Greg Stolze’s City of Lies for L5R, Monte Cook’s Ptolus, Chicago by Night, City of Freeport, and so forth. It’s just that they’re being designed for a narrative-based game structure that’s not particularly illuminating when it comes to urbancrawling.

Recently, however, we’re starting to see a resurgence in games that are willing to get a little experimental with their game structures. (This has been particularly true among STGs, but it’s also happening with RPGs.) The result has been a handful of “new school” urbancrawls.

DRESDEN FILES

When I first started chattering about urbancrawls, a lot of people pointed me in the direction of the Dresden Files. This game has gotten a lot of buzz for its robust city-creation system and I was told it might be exactly what I was looking for.

When I first started chattering about urbancrawls, a lot of people pointed me in the direction of the Dresden Files. This game has gotten a lot of buzz for its robust city-creation system and I was told it might be exactly what I was looking for.

Unfortunately, it’s not.

The city-creation system in Dresden Files is really a campaign creation system in which the creation of the city is tied to the creation of the PCs and the players share narrative responsibilities in defining the themes, threats, and locations which define the city. It’s a nifty approach (and I recommend checking it out), but the focus is still on creating a backdrop for narratives.

NIGHT’S BLACK AGENTS

Kenneth Hite’s Night’s Black Agents has an international focus, but it features two very clever systems for running conspiracy-based sandbox campaigns that I think may prove useful in our thinking about urbancrawls.

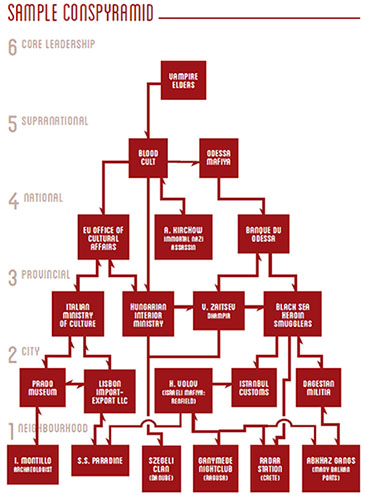

First, there’s the Conspyramid. When you’re prepping your campaign you draw up a Conspyramid with six levels of power: “Each ascending level has fewer, more important nodes.” So, at street-level power you’ve got six different nodes. Bump it up a couple levels to provincial powers and you’ve got four different nodes.

The Conspyramid is useful because it simultaneously shows the GM how the organization of the conspiracy works (in an abstract way) and how the PCs can investigate the conspiracy.

The Conspyramid is clever because Hite also ties it mechanically into the game mechanics: As the players fill out their adversary map (i.e., figuring out how the conspiracy hooks together), they gain dedicated pools of points to spend on ops targeting connected nodes on the Conspyramid. They can also use Human Terrain and Traffic Analysis skills to figure out the connections between a node they know and other nodes (i.e., generating leads).

That’s a default goal, a default reward, and a default action.

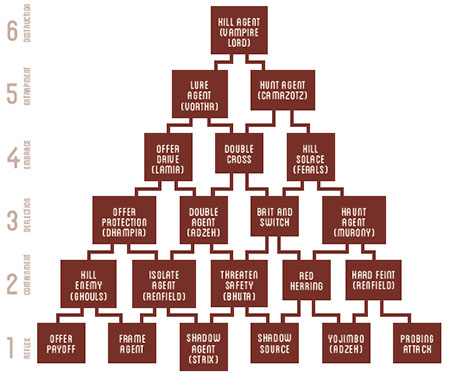

Hite then adds a second track in the form of the Vampyramid:

He describes this as an “escalating response algorithm” which provides the vampire conspiracy with a naturalistic response to the PCs: So the Conspyramid represents a largely static ‘crawl; the Vampyramid provides easy-to-manage active responses.

It’s the most innovative, creative, and gobsmackingly brilliant work I’ve seen on an RPG game structure in over a decade. Hite’s a genius and you should check it out.

(UPDATE: Hite has informed me that his own work on NBA was inspired by Elizabeth Sampat’s Blowback. I recommend checking that out, too.)

While these structures cannot be directly applied to the type of urbancrawling structure we’re looking for, where I think the NBA systems are extremely informative is the intersection of investigative “layers” combined with default, mechanically-driven investigative actions. (We’ll come back to this idea shortly.)

VORNHEIM

Vornheim by Zak S. proffers a quote about Moving vs. Crawling which is so extremely useful that I’m going to provide it here in full:

In a dungeon or wilderness adventure everything is hard – navigating, finding food, getting a decent night’s sleep, etc. – and so everything is part of the adventure. Adventuring in a city is different from adventuring in a dungeon or wilderness because cities are actually meant for habitation. In most cities, many things will be easy and therefore not part of the adventure and the GM has to do a great deal of deciding when to “zoom in” and deal with the situations in more detail. For this reason we’re going to create a distinction between simply “moving” through the city and “crawling” through it. (…)

“Crawling” occurs when:

• The PCs are being chased.

• The PCs are in a hurry.

• A large number of elements in the city are actively hostile to the PCs (such as during an invasion or plague of madness).

• The PCs are systematically searching a small area of the city for something.

• The PCs are trying to avoid running into someone or something.

• It’s night.

• The city is transformed in some way such that it ceases to function like a city (post-nuclear bomb, etc.).

• The PCs don’t really know where they’re going.

• There’s urgency attached to the PC’s decisions about how to proceed for any reason.

A lot of the Old School Renaissance has largely spent its time regurgitating the forms and content of the ‘70s and early-‘80s. (And, don’t get me wrong, produced a lot of good material doing it.) Vornheim is a prime example of the OSR being a little more daring, grounding itself in the old school material, and then innovating.

For ‘crawling, Vornheim creates a pair of simple structures: If you’re crawling from neighborhood to neighborhood (i.e., trying to traverse the city) you generate one random encounter per neighborhood. If you’re crawling within a neighborhood (i.e., they’re trying to find something in the neighborhood) he uses a method of rolling 2d10 and using:

• The relative position of the dice to determine where the goal of the ‘crawl is relative to the PCs.

• The number on the die to determine the layout of streets between them and their destination. (Literally. You can check out the diagrams of how this works here.)

It’s a very clever and quick system. Where it comes a little short is in providing structure for making the journey from Point A to Point B a meaningful/interesting one.

What makes Vornheim truly invaluable in any discussion about urbancrawling, however, is the plethora of incredibly cool, incredibly useful, and incredibly original tools that Zak has designed for procedural content generation. (This is something I talked about in my Fun With Vornheim series, which you should check out for some awesome examples of what the book is capable of.)

TECHNOIR

Technoir is another system I’ve talked about quite a bit. It’s got an incredibly clever resolution mechanic, but what makes the game truly exceptional are its plot-mapping mechanics.

The short version is that the game is built around “transmissions” which each describe a city of the future. Each transmission consists of six connections, six events, six factions, six locations, six objects, and six threats. These are organized into a 6 x 6 master grid which allows you to randomly generate elements and add them to your plot map.

By itself, that’s a nice little procedural generator. But Technoir takes it one step further by including explicit mechanics for how elements are added to the plot map, and the primary method is controlled by the PCs: Whenever they hit up one of their contacts for information, an element is generated based on the contact’s current relationship to the plot and it’s connected to the map based on situational mechanics as well.

By itself, that’s a nice little procedural generator. But Technoir takes it one step further by including explicit mechanics for how elements are added to the plot map, and the primary method is controlled by the PCs: Whenever they hit up one of their contacts for information, an element is generated based on the contact’s current relationship to the plot and it’s connected to the map based on situational mechanics as well.

(A lengthier example of using the Technoir system can be found here.)

The result is a robust improvisational structure which has the delightful property of allowing the GM to discover the “true conspiracy” of their ‘noir adventure at the same time that their players are investigating it. (It’s also a system which could be very easily translated to any genre or setting.)

In terms of urbancrawling, the key insight from Technoir is the ‘crawl action itself: Hitting up your contact.

What makes this notable is that this is not a decision about geographic navigation, but it nevertheless fulfills the same exploratory function. The only limitation is that this is a mystery-based structure and, as you’ve probably gotten sick of me saying, mysteries don’t work for open table play. Technoir solves the problem of being unable to solve the mystery if you missed the clues in the first half (by utilizing a structure which constantly manifests new clues), but you still have the problem of players experiencing the first half of a mystery and never getting the satisfaction of its solution. (But if you want an urbancrawling structure and you don’t need it to support open table play, then I enthusiastically recommend Technoir.)

This series of urban-crawling posts has been amazing. Thank you!

When I came to build the major city in my own setting, I looked at a few supplements and ended up using chapter 3 of the Fantasy Flight Games ‘City Works’ by Mike Mearls (2003).

It’s a bit too crunchy and in-depth, and slow – but by picking and choosing I was at least able to build the city to my satisfaction. Of course, the players never ended up spending much time there anyway, but it was a good exercise. I wouldn’t use it all again but I might crib a couple of ideas.