Go to Part 1

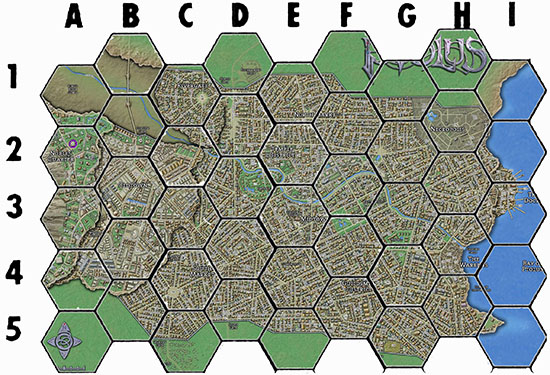

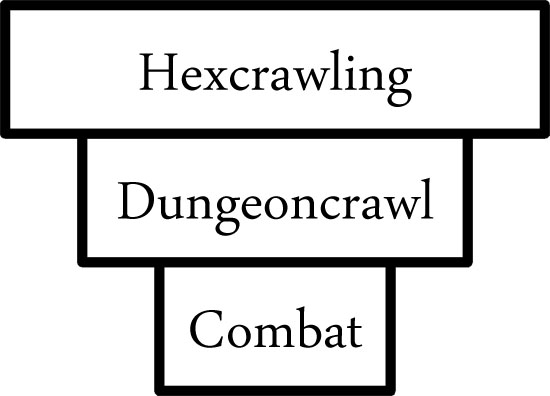

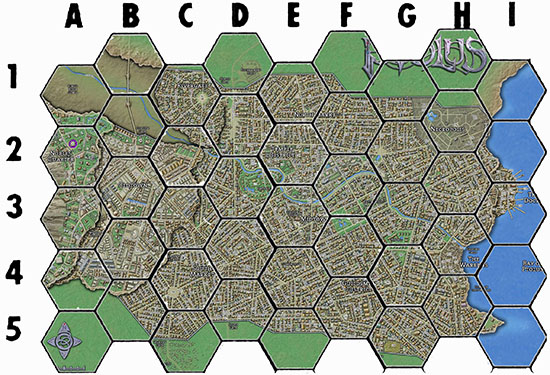

So what we’re going to do here is take a map of Monte Cook’s Ptolus and drape a hex map over it. Then we’re going to pull existing location keys from Cook’s description of the city and we’re going to use them to key the hexes.

I’m choosing Ptolus for this exercise because the city is densely packed with existing material that’s both utilitarian (apothecaries, marketplaces, and the like) and also studded with adventuring potential. The goal is to see if simply creating an urban-themed hexcrawl will provide any insight into an urbancrawling structure.

As I’m writing this, I have absolutely no idea if this is going to work. (And perhaps a secret little hope that it will miraculously turn into a fully functional urbancrawl and solve all my problems.)

THE MAP

(click for larger image)

THE KEY

As you’re looking through this key, remember that the urbancrawl key doesn’t represent all the information that you might prep about the city. For example, you might also prep a list of shop where potions are sold. Or make a note of where the popular (and unpopular) taverns are. (These would all obviously be things that would reside within the boundaries of the hexes, but they wouldn’t be interacted with through the urbancrawl structure.)

It should also be noted that this isn’t a complete key. For example, some of these locations would need full maps along with map keys. I’m not going to bother doing that right now, though, because the primary goal of this exercise is to look at what you’re keying.

A1. ZELLATH KORY’S HOUSE: A small house serving as the homebase for a Sorn cell. (The Sorns are a decentralized assassins’ and mages’ guild.) Zellath Kory is the cell leader.

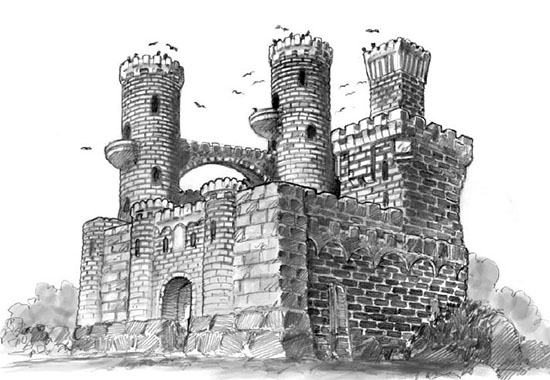

A2. CASTLE SHARD: A huge castle made from purple stone, housing a massive crystal with strange magical properties. It is ruled by Lord Zavere and Lady Rill.

A3. KADAVER’S: A secret bar for criminals hidden beneath a dilapidated manse.

A4. VLADAAM ESTATE: The noble estate of the Vladaam family. The Vladaams rule over a vast criminal network. The grounds are defended by a pack of warhounds.

B2. PYTHONESS HOUSE: A haunted castle. (Standard dungeon crawl described in the Night of Dissolution adventure.)

B3. CLOCK TOWER: A major landmark in Oldtown, the Clock Tower no longer works. A cellar below the Clock Tower leads to a very old family crypt that once lay under the manor that was built on this previous built on this spot. The crypt provides access to an underground complex known as the Buried City.

B4. SKULK ALLEY: An innocuous looking dead-end alleyway between a pair of buildings. Scrawled on the wall is the skulk symbol. Those who wait in the alley for at least half an hour are approached by Shim, a skulk willing to serve as an information broker and private detective.

B5. THE BOILING POT: A large and well-established slophouse run by a jovial fellow named Dellam Koll.

C1. WELL OF THE SHADOW EYES: A dry and disused well in a dead-end Rivergate alley. At the bottom of the well there’s a secret door leading to the underground Ravenstroke complex, a magical lair created by the wizard Aelian Fardream. It is now controlled by the Shadow Eyes, a magical clone of Fardream.

C2. CHAPEL OF ST. THESSINA: One of the many temples of Lothian found throughout the city. The chapel has been secretly taken over by the Pactlords of the Quaan (who have replaced the priests with doppelgangers and are using the upper levels for a variety of purposes).

C2. CHAPEL OF ST. THESSINA: One of the many temples of Lothian found throughout the city. The chapel has been secretly taken over by the Pactlords of the Quaan (who have replaced the priests with doppelgangers and are using the upper levels for a variety of purposes).

C3. GALLOWS SQUARE: A public square where the city’s executions are held.

C4. ROGUE MOON TRADING COMPANY: A three-story building serving as the base of operations for the largest merchant company in Ptolus. (Some people call it the Star of the South Market.) Tamora Riagin runs the office here.

C5. CHON: A clothier/tailor.

D2. RED STALLION PUB: The largest, most popular alehouse in the North Market. Co-owned by Yallis Kether and Utha Aryen. At night, the Red Stallion holds contests for drinking, singing, and throwing darts. (The winners get free drinks the following night.) A former delver named Jurgen Yath can also be found there, willing to sell information about the Dungeon beneath the city.

D3. SADIE’S REST: A memorial park dedicated to Sadie of the Moors. Bron Higger is the caretaker.

D4. RAMORO’S BAKERY: Ramoro Udelis and his wife Carlatia run this South Market bakery. The house itself is old and ill-kept, but the baked goods are excellent. Ramoro’s brother, Pauthan, is a pickpocket who “works” among the bakery’s customers.

D5. THE MYSTERY PUB: A tavern known for elaborate, bizarre, and magical games and entertainments.

E1. KILLRAVEN’S TOWER: An old stone tower that leans precariously to one side and appears to be abandoned. Word on the street is that it’s actually the secret entrance to Kellris Killraven’s underground stronghold. (Killraven is attempting to establish a new crime family in Ptolus.) In reality, however, it has nothing to do with Killraven.

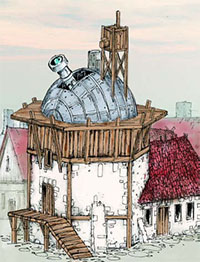

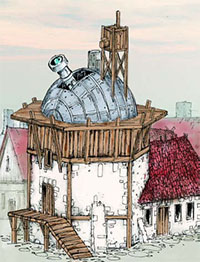

E2. TEMPLE OBSERVATORY OF THE WATCHER OF THE SKIES: The most distinctive portion of this temple is the cylindrical observatory with its giant telescope, used to observe significant events and omens in the skies, particularly the night sky. The temple is run by Helmut Itlestein, also known for being the head of the controversial Republican movement.

E2. TEMPLE OBSERVATORY OF THE WATCHER OF THE SKIES: The most distinctive portion of this temple is the cylindrical observatory with its giant telescope, used to observe significant events and omens in the skies, particularly the night sky. The temple is run by Helmut Itlestein, also known for being the head of the controversial Republican movement.

E3. GHOSTLY MINSTREL: An inn, pub, and restaurant all in one. It’s become the meeting place of choice for delvers and adventurers. The Minstrel is haunted by an actual undead bard.

E4. BLACKSTOCK PRINTING: Blackstock is one of the few businesses in the city with a functioning, large-scale movable type printing press. (Many of the city’s newssheets are printed here.) What is not widely known is that the press is controlled by six of Aelian Fardream’s clones (who were awakened from temporal stasis due to a strange magical surge several years ago).

E5. COCK PIT: An underground cockfighting arena which has grown into one of the largest illegal gambling dens in Ptolus.

F2. CATTY’S HOUSE: A small house serving as the homebase for a Sorn cell. (The Sorns are a decentralized assassins’ and mages’ guild.) Katrin “Catty” Salla is the cell leader.

F3. TEMPLE OF THE FROG: An abandoned ruin. The vile cultists who once ran this temple were driven out by adventurers six years ago.

F4. KERRIK’S: The proprietor of this bar, Kerrik Tanner, is also a contact point for the Vai assassins.

F5. WOODWORKER’S GUILDHALL: Run by Guildmaster Falen Jenn.

G1. NALL HALL: A cultural center for people from the northern wasteland of Nall or those who have descended from Nallish folk. They hold dances, feasts, and festivals to preserve their traditions – but all are welcome. (At the festival, PCs will be approached by a young woman named Sanne who is trying to find someone to look for her husband, Sebastin. Sebastin disappeared on a delving mission in the Dungeon below the city while using a map that he purchased from someone at the Red Stallion Pub.)

G2. SMOKE SHOP: The Shuul mechanists’ guild sells cutting-edge technological items here – spectacles, watches, spyglasses, magnifying lenses, goggles, precision tools, pills of various kinds, and (their newest creation) the aelectrical lantern. They also sell all manner of firearms and technological weaponry. Crimson Coil cultists have been stealing gunpowder from the shop in order to construct a huge bomb.

G3. TERREK NAL’S HOUSE: Terrek Nal was apprenticed to the mage Golathan Naddershrike. Naddershrike proved a cruel master cursed him with a monstrous appearance, Nal murdered him in rage. After the murder, Nal returned to his family home and remains there in seclusion: The right half of his body is a glaring red and pink, slick with pus and strange excretions. He emits a foul stench too powerful to cover with perfumes. The greatest, change, however, is not physical: Nal now gains sustenance from fear instead of food and drink. When driven to desperation, he ventures out of his house and terrorizes people – he doesn’t harm them, merely frightens them in order to survive. A wealthy businessman who was assaulted three days ago has put a bounty of 500 gp on the monster’s head, describing his assailant as “a twisted man-thing with melted flesh”.

G4. POTIONS AND ELIXIRS: A well-stoked alchemical supply and potion store. The sole proprietor is a half-elf sorcerer named Buele Nox.

G5. MIDDEN HEAPS: A huge trash dump backed up against the southern city wall. The merchants in charge of the heaps charge a small fee for the dumping of trash (and for a little extra won’t bother inspecting it too closely). They’ll also sell scrap and broken items for 5cp per pound. Ratmen, goblins, and even otyughs are known to make their homes amidst the towering piles.

H3. DAYKEEPER’S CHAPEL: The Daykeeper’s Chapel is charged with beginning the ringing of the dawn bells each day (the other chapels take their cue from its beginning). Sister Arsagra Callinthan also oversees a variety of charitable outreach programs into the warrens. At the moment, Sister Arsagra has offered sanctuary to a man named Kobal who is being hunted by the Pale Dogs. (Kobal has discovered that Jirraith is a doppelganger.)

H4. JIRRAITH’S LAIR: The Pale Dogs are the most prominent of the gangs in the Warrens. They’re led by a mysterious man named Jirraith who keeps his “headquarters” in the top floor of an average-looking tenement. He has no bodyguards there, but he has a trained gibbering mouther. Even his lieutenants don’t know that Jirraith is actually a doppelganger.

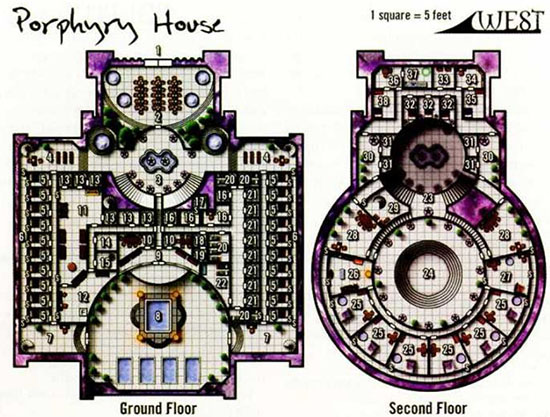

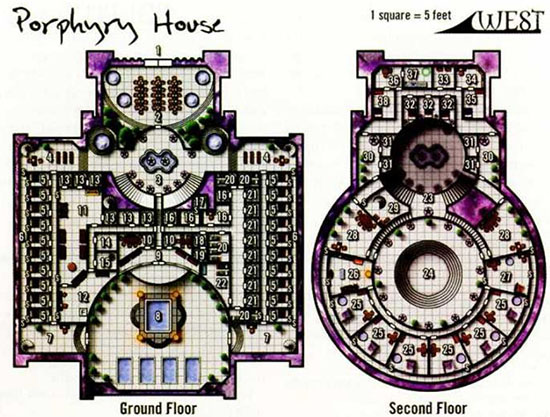

H5. PORPHYRY HOUSE: A vile whorehouse secretly run by naga mistresses. The whores are actually polymorphed hydra hatchlings.

I2. DOCKMASTER’S TOWER: A strangely-shaped tower that looks out across the Docks. The Dockmaster who lives within maintains all the crew and cargo manifests, inspection reports, and shipping information that pertains to any craft that enters or leaves Ptolus. In fact, an officer from each ship must check in with the Dockmaster immediately upon arrival and immediately before departure. The Dockmaster, however, is grotesquely obese and never leaves the upper level of the tower: He transfers paperwork and messages via a basket on a string outside one window. For anything more, he has a small girl named Secki (age 8) who works for him.

I3. ENNIN HEADQUARTERS: The headquarters of the Ennin slavers (who work with the Pactlords of the Quaan).

Go to Part 5: Using the Ptolus Hexmap