ASR’s script for Richard II is based primarily on the first Quarto of the play as it was published in 1597 (Q1). The decision to use Q1 as the source text of the play is based primarily on the relationship between the original texts as described by A.W. Pollard in 1916.

ASR’s script for Richard II is based primarily on the first Quarto of the play as it was published in 1597 (Q1). The decision to use Q1 as the source text of the play is based primarily on the relationship between the original texts as described by A.W. Pollard in 1916.

RICHARD II — FULL SCRIPT

RICHARD II — CONFLATED SCRIPT

Pollard was able to demonstrate (by tracing the inheritance of typographical errors from one edition to the next) that each quarto after the first was based entirely on the printed copy of the previous quarto: Thus Q2 was printed from Q1; Q3 from Q2; and so forth. (Richard II actually proved to be one of Shakespeare’s most popular plays in quarto. Other than Pericles, it is the only play to receive two quarto printings in the same year.)

The exception to this rule is Q4 in 1608, which adds a version of the deposition scene to the play. The leading theory is that the deposition, despite its central importance to the structure of the play, was simply too controversial in the waning years of Queen Elizabeth’s reign for it to be printed. (Another book regarding the usurpation of Richard II’s throne by Henry Bullingbrooke had already become the center of a major political scandal.)

The other text to consider is the First Folio (F1). Textual evidence seems to indicate that the F1 text was based on one of the later quartos, but it also includes additional stage directions (suggesting access to the theater’s prompt script) and a superior version of the deposition scene than the one found in Q4 (which reportedly shows signs of memorial reconstruction). But the exact nature of F1’s source text is a matter of considerable debate which can basically be broken down into two separate issues:

(1) Which quarto is the F1 text based on? (Some point to Q3. Others to Q5. Many to some combination of Q3 and Q5. But was it a single text assembled from a part of Q3 and a part of Q5, or did the typesetters have both a Q3 and Q5 laying around and simply consulted whichever was most convenient?)

(2) Was the quarto text being used as a promptbook (with stage directions being added to the printed copy and, thus, added to the F1 text)? Or was the promptbook being consulted separately with its stage directions and perhaps other corrections being incorporated into a text being set from the printed quarto?

To these questions we can add:

(3) What was the source of the Q4 deposition? (Memorial reconstruction is often one suggestion, but not a completely compelling one.)

(4) From what source was F1’s deposition scene (and possibly other corrections) taken from?

I have accepted the general scholastic conclusion that F1 is the superior source for the deposition scene, but since the F1 text is at least partly derived from a quarto text we know to be derivative of Q1, I have decided to employ the following textual standard:

Q1 is used as a source text. F1 is used as the source text for the deposition scene. F1 is also used to provide necessary corrections to the Q1 text, although if the correction originated in quarto editions between Q2 and Q5 (likely making it no more than a typesetter’s best guess), I don’t give it any more weight than other emendations.

STAGE DIRECTIONS FROM HOLINSHED

One final point of interest in the text are the stage directions for Act V, Scene 5 (in which Richard is murdered). In the original Q1 text, the scene appears like this:

KEEPER My lord I dare not; Sir Pierce of Exton,

Who lately came from the King commands the contrary.

RICHARD The devil take Henry of Lancaster, and thee,

Patience is stale, and I am weary of it.

KEEPER Help, help, help.

The murderers rush in.

RICHARD How now, what means Death in this rude assault?

Villain, thy own hand yields thy death’s instrument.

Go thou, and fill another room in hell.

Here Exton strikes him down.

The First Folio provides us with the identities of the murderers (“Enter Sexton and Servants“), but still leaves us with a lot of unanswered questions: What prompts the Keeper to call for help? And should we interpret “Villain, thy own hand yields thy death’s instrument” as a dramatic invocation (and perhaps foreshadowing) of the fate that awaits those who murder kings?

The description of the scene found in Holinshed’s Chronicles, on the other hand, may help to shed some light on it:

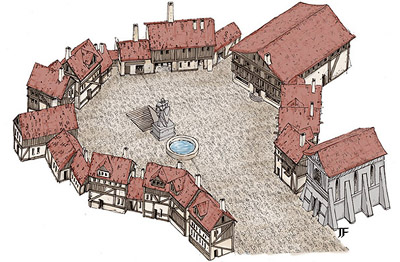

King Henry, sitting on a day at his table, sore sighing, said, “Have I no faithful friend which will deliver me of him, whose life will be my death, and whose death will be the preservation of my life?” This saying was much noted of them which were present, and especially of one called Sir Piers of Exton. This knight incontinently departed from the court, with eight strong persons in his company, and came to Pomfret, commanding the esquire that was accustomed to sew and take the assay before King Richard to do so no more, saying: “Let him eat now, for he shall not long eat.” King Richard sat down to dinner and was served with courtesy or assay, whereupon much marveling at the sudden change, he demanded of the esquire why he did not his duty, “Sir” (said he) “I am otherwise commanded by Sir Piers of Exton, which is newly come from King Henry.” When King Richard heard that word, he took the carving knife in his hand, and struck the esquire on the head, saying, “The devil take Henry of Lancaster and thee together.” And with that word, Sir Piers entered the chamber, well armed, with eight tall men likewise armed, every of them having a bill in his hand.

King Richard, perceiving this, put the table from him, and stepping to the foremost man, wrung the bill out of his hands, and so valiantly defended himself that he slew four of those that thus came to assail him. Sir Piers being half dismayed herewith, leapt into the chair where King Richard was wont to sit, while the other four persons fought him and chased him about the chamber. And in conclusion, as King Richard traversed his ground from one side of the chamber to the other, and coming by the chair where Sir Piers stood, he was felled with a stroke of a pole-axe which Sir Piers gave him upon the head, and therewith rid him out of life.

The fact that Shakespeare drew directly from this passage can be seen in its many similarities to the text of the play. In addition, it is relatively easy to see how the action described by Holinshed can be fitted to Shakespeare’s verse:

KEEPER My lord I dare not; Sir Pierce of Exton,

Who lately came from the King commands the contrary.

[Richard takes the carving knife and strikes the Keeper on the head.]

RICHARD The devil take Henry of Lancaster, and thee,

Patience is stale, and I am weary of it.

KEEPER Help, help, help.

<Enter Exton and Servants.>

The murderers rush in.

RICHARD How now, what means Death in this rude assault?

[Richard takes a halberd from one of them, killing several of them.]

Villain, thy own hand yields thy death’s instrument.

Go thou, and fill another room in hell.

Here Exton strikes him down.

While consistent, however, it should be noted that the exact timing of them and perhaps even their details are open for negotiation in actual production.

As an interesting note, the Moby Shakespeare on which virtually all online versions of Shakespeare are based includes a stage direction for Richard which reads: “Snatching an axe from a Servant and killing him.” (This direction is from the 1864 Globe Shakespeare on which the Moby Shakespeare takes its text.) But there’s no textual basis for Richard ending up with an axe, and Holinshed makes it clear the opposite is true: Richard employed a bill (or halberd). He was in fact killed by an axe, not wielding one.

TEXTUAL PRACTICES

Source Text: First Quarto (1597)

1. Original emendations in [square brackets]; emendations taken from F1 in <diamond brackets>; emendations taken from Q2 thru Q5 in {curly brackets}.

2. Speech headings silently regularized.

3. Names which appear in ALL CAPITALS in stage directions have also been regularized.

4. Spelling has been modernized.

5. Punctuations has been silently emended (in minimalist fashion).