Named after Myliesha, an elven goddess of the wind (Ptolus, p. 73), the Myliesh’a Sail is the smallest vessel in the Fleet of Iron Sails. It’s notable for being the only ship in the fleet not armed with cannon or ballista. The absence of ship weaponry allows the Sail to avoid inspections at certain foreign ports, making it easier for them to engage in smuggling, slave-trade, and other illicit activities.

CAPTAIN CROTIKA: Use stats for pirate captain (MM 2024, p. 242).

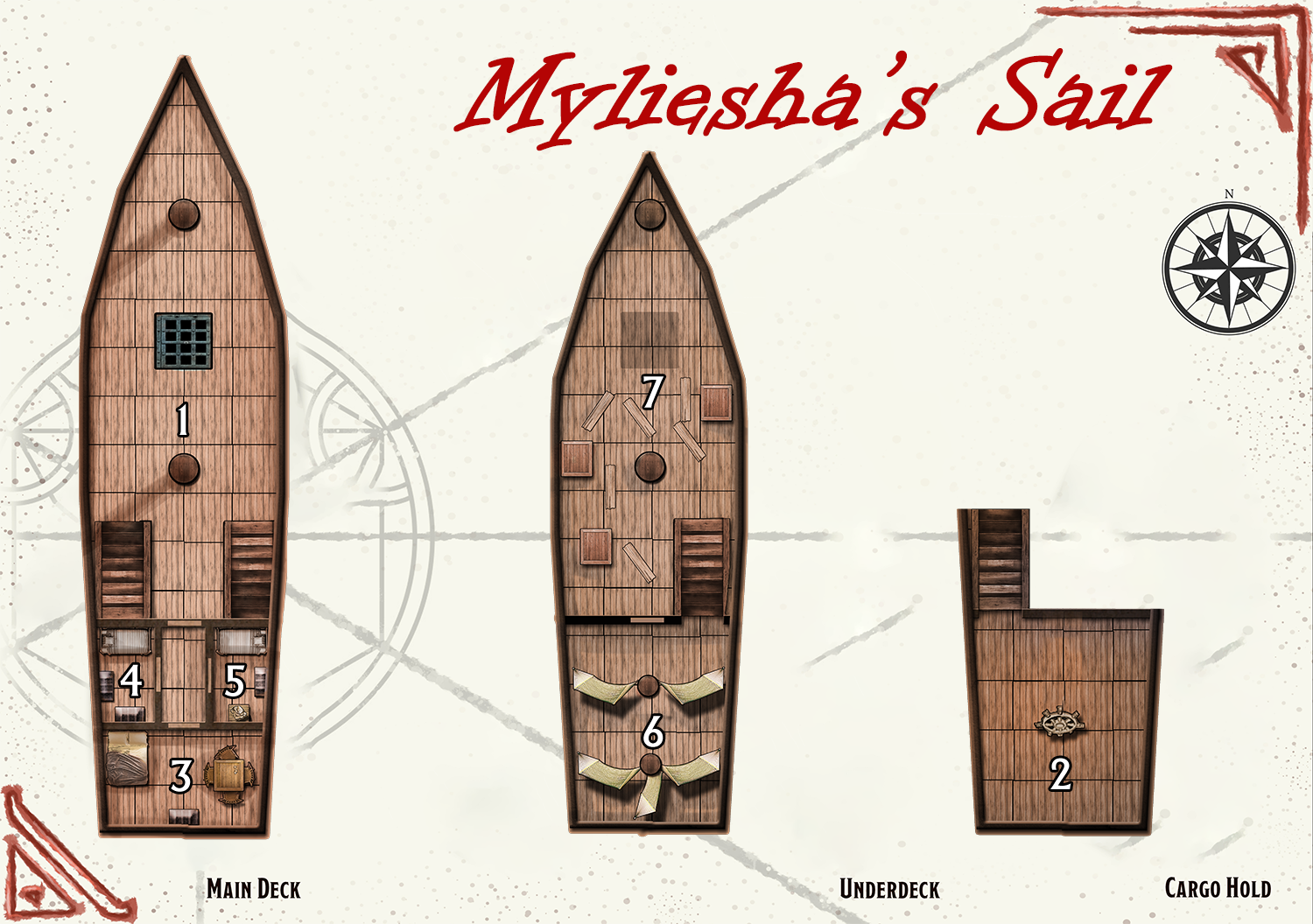

SHIP’S MAP: Fat Goblin Games’ Simple Ship battlemap.

AREA 1 – MAIN DECK

The deck is well-scrubbed and kept in good order. Despite this, a large, black stain extends from the cargo hatch and runs for several feet across the deck. (Anyone watching onboard activity will notice that crewmembers avoid stepping on the stain.)

STAIN: Careful inspection notes that there are small arcane runes carved into the surface of the stain. Anyone stepping on the stain is must make a DC 12 Wisdom saving throw or be affected as per bestow curse.

DC 14 Intelligence (Arcana): The stain is from a blood curse. Someone cursed their own blood and then spilt it upon the deck in order to place a curse upon the Myliesha’s Sail. (GM Note: This was a lizardman witch who was being transported as a slave.)

DC 18 Intelligence (Arcana): The arcane runes are designed to seal in the curse. This prevents it from affecting the ship, but it would still be a good idea to avoid stepping on it.

CARGO HATCH: The cargo hatch is secured with a pair of hefty padlocks.

- AC 19, 7 hp, DC 18 Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools)

AREA 2 – THE WHEEL

The wheel is coated with dragon bile (contact poison, DC 20 Constitution saving throw, 5d6 poison damage (half on save), and disadvantage on Strength checks). Crewmembers know to wear gloves while steering the ship.

AREA 3 – CAPTAIN’S QUARTERS

TABLE: On the table is a small mahogany box containing a ring of counterspells (a serpent of mithril and a serpent of taurum, the true gold, swallowing each other’s tails) and Letter to Guildmaster Arzan (see handouts).

Ring of Counterspells (rare, requires attunement)

This ring might seem like a ring of spell storing upon first examination. However, while it allows a single spell of 1st through 5th level to be cast into it, that spell cannot be cast out of the ring again. Instead, should that spell ever be cast upon the wearer, the spell is immediately countered, as if per a counterspell. If a counterspell is casting into the ring, it can be used to counter any spell, as per the spell.

Once used, the spell cast within the ring is gone. A new spell (or the same one as before) may be placed in it again.

GM Background: This ring was recovered from ruins in the Serpent’s Teeth. It currently contains a gate seal spell and it’s possible the Red Magi might be able to research the spell by studying the ring. (The gate seal spell can be found in Planescape: Sigil and the Outlands.)

IRON COFFER: 465 gp, 79 pp, potion of blur

- Lock: DC 16 Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools)

AREA 4 – SHIP SUPPLIES & ARMORY

In addition to hard tack, barrels of water, rope, and other necessary supplies, this room contains an unusual number of weapons:

- scimitars & dragon pistols (Ptolus, p. 522), enough to arm the sailors

- dragon rifles (Ptolus, p. 522) to arm the Advanced Vladaam Guards

AREA 5 – VLADAAM MAGE’S QUARTERS

The Vladaam Mage assigned to the ship keeps their quarters here. Their personal belongings include their spellbook, a potion of superior healing, and a shield of missile attraction (that they’re studying).

AREA 6 – CREW QUARTERS

This chamber is filled with crisscrossing hammocks and where most of the crew sleep.

DOOR: The door leading to the hold is steel-cored and securely locked.

- AC 19, 40 hp, DC 18 Dexterity (Thieves’ Tools)

AREA 7 – HOLD

Although Myliesha’s Sail transports slaves, they usually carry no more than a half load, and often much less than that.

Greater effort is made to keep the hold well maintained and cleaned (with the Vladaam Mages using prestidigitation spells, among other measures), making it easier for the ship to fulfill its role as a smuggler when the hold is used for mundane goods (or seemingly mundane goods).