A question I’m asked with surprising regularity is, “Why do you waste money on adventure modules?” It’s a question generally voiced with varying degrees of disdain, and the not-so-hidden subtext lying behind it is that published adventure modules are worthless. There are different reasons proffered for why they should be ignored, but they generally boil down to a couple of core variations:

A question I’m asked with surprising regularity is, “Why do you waste money on adventure modules?” It’s a question generally voiced with varying degrees of disdain, and the not-so-hidden subtext lying behind it is that published adventure modules are worthless. There are different reasons proffered for why they should be ignored, but they generally boil down to a couple of core variations:

(1) Published adventures are for people too stupid or uncreative to make up their own adventures.

(2) Published adventures are crap.

The former makes about as much sense to me as saying, “Published novels are for people too stupid or uncreative to write their own stories.” And the latter seems to be derived entirely from an ignorance of Sturgeon’s Law.

On the other hand, I look at my multiple bookcases of gaming material and I know with an absolute certainty that I own more adventure modules than I could ever hope to play in my entire lifetime. (And that’s assuming that I never use any of my own material.)

So why do I keep buying more?

There are a lot of answers to that. But a major one lies in the fact that I usually manage to find a lot of value even in the modules that I don’t use.

Take, for example, Serpent Amphora 1: Serpent in the Fold. While being far from the worst module I’ve ever read (having been forced to wade through some true dreck during my days as a freelance reviewer), Serpent in the Fold is a completely dysfunctional product. It’s virtually unsalvageable, since any legitimate attempt to run the module would necessitate completely replacing or drastically overhauling at least 90% of the content.

A QUICK REVIEW

The only thing worse than a railroaded adventure is a railroaded adventure with poorly constructed tracks.

For example, it’s virtually a truism that whenever a module says “the PCs are very likely to [do X]” that it’s code for “the GM is about to get screwed“. (Personally, I can’t predict what my PCs are “very likely to do” 9 times out of 10, and I’m sitting at the same table with them every other week. How likely is it that some guy in Georgia is going to puzzle it out?) But Serpent in the Fold keeps repeating this phrase over and over again. And to make matters worse, the co-authors seem to be in a competition with each other to find the most absurd use of the phrase.

(My personal winner would be the assumption that the PCs are likely to see a group of known enemies casting a spell and — instead of immediately attacking — they will wait for them to finish casting the spell so that they can spy on the results.)

Serpent in the Fold gets bonus points for including an explicit discussion telling the GM to avoid “the use of deus ex machina” because it “limits the PCs”… immediately before presenting a railroaded adventure in which the gods literally appear half a dozen times to interfere with the PCs and create pre-determined outcomes.

The module then raises the stakes by encouraging the DM to engage in punitive railroading: Ergo, when the PCs are instructed by the GM’s sock puppet to immediately go to location A it encourages the GM to have the PCs make a Diplomacy check to convince a ship captain to attempt dangerous night sailing in order to get to their destination 12 days faster than if the captain plays it safe. The outcome of the die roll, however, is irrelevant because the PCs will arrive only mere moments after the villains do whether they traveled quickly or not. On the other hand, if the PCs ignore the GM’s sock puppet and instead go to location B first for “even a few days” then “they will have failed” the entire module.

So, on the macro-level, the module is structurally unsound. But its failures extend to the specific utility of individual sequences, as well: The authors are apparently intent on padding their word count, so virtually all of the material is bloated and unfocused in a way that would make the module incredibly painful to use during actual play.

The authors are also apparently incapable of reading the rulebooks. For example, they have one of the villains use scrying to open a two-way conversation with one of their minions. (The spell doesn’t work like that.) More troublesome is when the PCs get the MacGuffin of the adventure (a tome of lore) and the module confidently announced that it has been sealed with an arcane lock spell cast by a 20th level caster and, therefore, the PCs won’t be able to open it. The only problem is that arcane lock isn’t improved by caster level and the spell can be trivially countered by a simple casting of knock.

The all-too-easy-to-open “Unopenable” Tome is also an example of the authors engaging in another pet peeve of mine: Writing the module as if it were a mystery story to be enjoyed by the GM. Even the GM isn’t allowed to know what the tome contains, so when the PCs do manage to open it despite the inept “precautions” of the authors he’ll be totally screwed. And the tome isn’t the only example of this: The text is filled with “cliffhangers” that only serve to make the GM’s job more difficult. The authors actually seem to revel in serial-style “tune in next week to find out the shocking truth!” nonsense.

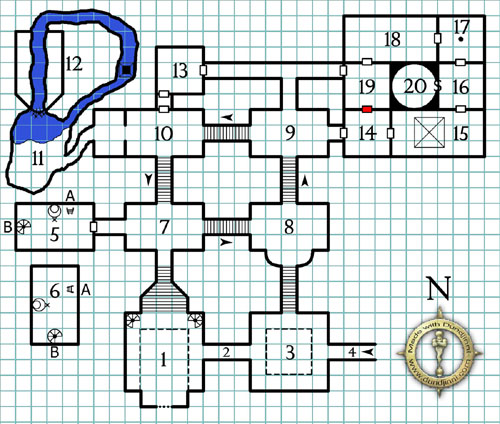

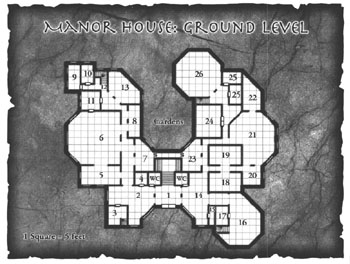

Maps that don’t match the text are another bit of garden-variety incompetence to be found in Serpent in the Fold, but the authors raise it to the next level by choosing to include a dungeon crawl in which only half the dungeon is mapped. The other half consists of semi-random encounters strewn around an unmapped area of wreckage which are too “haphazard” to map and key. Despite this, the encounters all feature very specific topographical detail that the authors are then forced to spend multiple paragraphs describing in minute detail. (Maps, like pictures, really are worth a thousand words.)

As if to balance out this odd negligence, the authors proceed to round out the final “chapter” of the adventure by providing an exhaustive key to a mansion/castle with 50+ rooms… which the GM is than advised to ignore. (And I mean this quite literally: “In order to [“get right to the action”] have them notice the bloodstains in the entry foyer, and thus, likely, find the bodies. Make the trail that leads to the infirmary a bit more obvious […] it should be easy to keep the PCs moving up the stairs and to the final confrontation with Amra.”) In this case, the advice is quite right: The pace of the adventure is better served if the PCs don’t go slogging through a bunch of inconsequential rooms. But why is a third of the module dedicated to providing a detailed key that will never be used?

Round out the package with a handful of key continuity errors and elaborate back-stories and side-dramas featuring NPCs that the PCs will never get to learn about (another pet peeve of mine) to complete the picture of abject failure.

THE STRIP MINE

I tracked down the Serpent Amphora trilogy of modules in the hope that I would be able to plug them into a potential gap in my Ptolus campaign. Unfortunately, it turned out that the material was conceptually unsuited for my needs and functionally unusable in its execution. So that was a complete waste of my money, right?

Not quite.

To invent a nomenclature, I generally think of adventure modules in terms of their utility:

Tier One modules are scenarios that I can use completely “out of the box”. There aren’t many of these, but a few examples would include: Caverns of Thracia, Three Days to Kill, In the Belly of the Beast, Death in Freeport, Rappan Athuk, and The Masks of Nyarlathotep. Tier One modules might receive some minor customization to fit them into my personal campaign world or plugged into a larger structure, but their actual content is essentially untouched.

Tier Two modules are scenarios that I use 80-90% of. The core content and over-arcing structure of these scenarios remains completely recognizable, but they also require significant revision in order to make them workable according to my standards. High quality examples include The Night of Dissolution, Banewarrrens, Tomb of Horrors, The Paxton Gambit, Beyond the Mountains of Madness, and Darkness Revealed. (For a more extreme version of a Tier Two module, see my remix notes for Keep on the Shadowfell.)

Serpent in the Fold is a Tier Three module: These are the modules which are either too boring or too flawed for me to use, but in which specific elements can be stripped out and reused.

(Tier Four modules are the ones with interesting concepts rendered inoperable through poor execution. Virtually nothing of worth is to be found here, since you’re largely doing the equivalent of taking the back cover text from a book and writing a new novel around the same concept. Tier Five modules are those rare and complete failures in which absolutely nothing of value can be found; the less said of them, the better.)

For example, consider that mansion with high quality maps and a detailed key for 50+ rooms.

That mansion is practically plug-‘n-play. Less than 5% of it is adventure specific. That’s an incredibly invaluable resource to have for an urban campaign (like the one I’m currently running).

But the usefulness of Serpent in the Fold doesn’t end there. I’ll be quite systematic in ripping out the useful bits of a Tier Three module (since I have little interest in revisiting the material again). Starting from the beginning of the module, I find:

Inside Cover: A usable map of a simple cave system.

Page 10: Three adventuring companies are detailed. (These are particularly useful to me because Ptolus feature a Delvers’ Guild full of wandering heroes responding to the dungeon-esque gold rush of the city. Ergo, there’s plenty of opportunities for the PCs to bump into competitors or hear about their exploits. Such groups are useful for stocking the common room of an inn or pub in any campaign.)

Page 25: An interesting mini-system for climbing a mountain. It features a base climbing time and a system for randomly generating the terrain to be climbed (prompting potential Climb checks which can add or subtract from the base climbing time). I’d probably look to modify the system to allow additional Survival or Knowledge (nature) checks to plot the course of ascent (to modify or contribute to the largely random system presented here).

Page 27: A very nice illustration that I can quickly Photoshop and re-purpose as a handout depicting a subterranean ruin.

(As a tangential note: I wish more modules would purpose their illustrations so that they could be used as visual aids at the gaming table. You can make your product visually appealing and useful at the same time, and you’re already spending the money to commission the illustration in any case.)

Page 33: Another useful illustration that can be quickly turned into a handout.

Page 54-55: A new monster and the new spell required to create them.

The module also features countless stat blocks, random encounter tables, and similar generic resources that can be quickly ripped out and rapidly re-purposed.

So even in a module that I found largely useless and poorly constructed, I’ve still found resources that will save me hours of independent work.

When you’re dealing with a module like Serpent in the Fold that you have no intention of ever using, these strip-mining techniques can be used to suck out every last drop of useful information without any particular care for the husk of detritus you leave behind. But similar measures can also be employed to harvest useful material from any module, even those you’ve used before or plan to use in the future.