A couple years ago I reviewed Weird Discoveries, a collection of ten “Instant Adventures” for Numenera using an innovative scenario format featuring:

A couple years ago I reviewed Weird Discoveries, a collection of ten “Instant Adventures” for Numenera using an innovative scenario format featuring:

- Two page description of the scenario’s background and initial hook.

- Two page spread that has “everything you need to run the adventure”.

- Two pages of additional details that can be used to flesh out the scenario.

The general idea being that the GM will be able to pick up one of these scenarios, rapidly familiarize themselves with it, and be able to run it with confidence in roughly the same amount of time that it takes for the players to familiarize themselves with some pregenerated characters (which are also included in the book). Basically, you lower the threshold for spending the evening playing an RPG to that of a board game: You can propose it off-the-cuff and be playing it 15 minutes later. And since I’ve been preaching the virtues of open tables and the importance of getting RPGs back to memetically viral and easily shared experience they were in the early days of D&D, that’s obviously right up my alley.

Last year, Monte Cook Games released Strange Revelations, which basically took the exact same concept and applied it to The Strange, their other major game line. I did not immediately read through it because, at the time, there was a plan in place for me to actually play in a campaign where the GM was going to use these scenarios. Those plans fell through, unfortunately, but now I’m in a position where I’m running a campaign of The Strange and I’m naturally tapping Strange Revelations as a resource for scenarios.

INSTANT ADVENTURES: THE VERDICT

Since 2015, I’ve actually spent a considerable amount of time interacting with MCG’s Instant Adventure format under a variety of use-types: Using them as one-shots, incorporating them into ongoing campaigns, running them at conventions, using them with and without prep, etc.

Unfortunately, the more time I spend with them, the less I like them.

Part of the problem, I think, is that the basic structure of the format is a limitation: It only really works with certain kinds of adventures. Unfortunately, it’s become a one-size-fits-all format for Monte Cook Games, and so they end up trying to cram every type of adventure into the format. (This is something I talk about in the Art of the Key: When you become a slave to your format instead of using the format and structure that’s appropriate for the specific content you’re creating it never ends well.)

There also seem to be some systemic problems with the specific execution of the format. These prominently include:

Keys. As discussed at length in my original review of Weird Discoveries, the Instant Adventure format uses Keys to highlight essential elements for the scenario — either some crucial item or clue without which the scenario cannot be resolved. But rather than simply include these Keys in the scenario, they are optionally coded into different scenes or locations using an icon which refers back to a table on a different page that describes what the Keys are.

The most immediate problem is that by putting literally the most crucial information on a different page, MCG fundamentally sabotages the entire concept of the central two page spread being the only thing you need to look at during play.

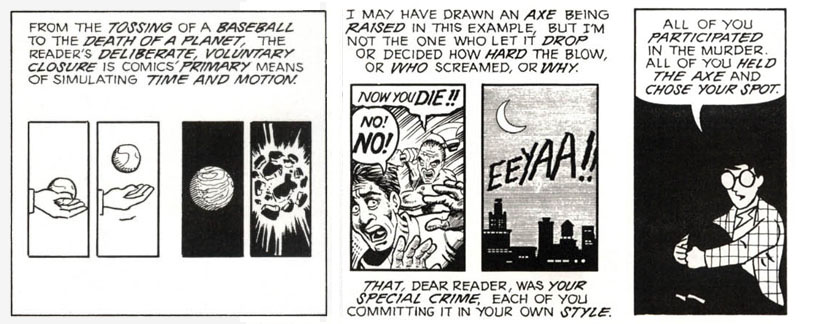

But the more insidious problem, as I’ve discovered, is that good scenario design is not in the generic; it is in the specific. Figuring out how information flows to the players during a mystery, for example, is a key difference between a good mystery scenario and a mediocre one. By genericizing the core elements of the scenario, the Instant Adventures format lends itself to mushy, generic scenarios that are, as a result, largely forgettable.

Bad Cartography: Inexplicably, many of the two-page spreads consist of sketchy, vague maps that have keyed content “associated” with them by having arrows pointing at semi-random locations on them. Strange Revelations is slightly better in this regard than Weird Discoveries, but it’s still frequently problematic. For example, here’s the map from one adventure paired with the graphical handout depicting what it’s supposedly mapping:

Confusing Graphical Handouts: This ties into another problem with the book. It includes 10 pages of pictorial handouts — referred to as “Show ‘Ems” — that are designed for the GM to hand to the players. I absolutely love pictorial handouts. The problem is that I would classify the majority of these as being functionally unusable. They do things like:

- Depict things which don’t match the text of the adventure (like the spaceship above).

- Include random characters who don’t appear in the text of the adventure. (Are they meant to be the PCs?)

- Spoil surprises. (For example, there’s one scenario where the PCs are supposed to get attacked by bad guys after arriving onsite… except the Show ‘Em depicting the site shows the bad guys standing there waiting for the PCs. I ended up photoshopping them out in order to use the picture.)

To be fair, many of these problems have afflicted pictorial handouts since The Tomb of Horrors first pioneered the form. But I nevertheless remain disappointed every time I see these get fumbled (partly because I always get so excited at the prospect of it being done right).

GM Intrusion Misuse: For some reason, MCG’s Instant Adventures frequently describe scenario-crucial events as “GM Intrusions”. (Possibly because the format doesn’t include any other way to key this content in some cases?) The problem is that, in the Cypher System, players can use XP to negate GM Intrusions. (See The Art of GM Instrusions.) So what these scenarios basically end up saying is, “Offer your players the opportunity to spend 1 XP to NOT receive the clue they need to solve the mystery.”

Too Short: Probably the most significant problem, however, is when the struggle to cram material into the two page spread causes a scenario to come up short. Literally. There are simply too many examples of Instant Adventures that are supposed to fill an evening of gaming or a 4 hour convention slot which consist of only 3-4 brief scenes. For example, there’s a scenario in Strange Revelations which consists of:

- Seeing a wall with a symbol spray-painted on it.

- Talking to an NPC.

- Talking to a second NPC.

- Being ambushed by a single NPC.

- A final fight vs. a single NPC.

Maybe your mileage varies. But for me, that might fill a couple hours of game play.

WHY YOU MIGHT STILL BUY IT

… if you’re a big fan of The Strange.

I’m not sure whether Strange Revelations suffers more regularly from these systemic failures than the scenarios in Weird Discoveries, or if I’ve just gotten more sensitive to these problems as a result of running face-first into them so many times. If it’s the former, I suspect it’s because Strange Revelations is so often struggling to force material that’s not really appropriate for the format into the format. Cordell does some very clever things trying to make the format work, but it’s clear that he’s got some really cool ideas for scenarios that are just being hamstrung by the necessity of making them work (or sort-of work) as Instant Adventures.

And it’s that “cool idea” factor that is why, ultimately, I found value in this book and suspect that you might find value, too: Above all else, Strange Revelations gives you 10 separate scenarios for $24.99 (or $10 in PDF). At as little as $1 per scenario, it can have a lot of rough edges and still be worth the effort sanding down the edges. At the moment it looks as if, with near certainty, I’ll be using at least 8-9 of these scenarios at my gaming table (with various amounts of tender loving care), and in my experience that’s a pretty good hit rate for a scenario anthology.

It’s just incredibly frustrating to see an idea with so much potential greatness as the Instant Adventures so consistently come up just short of achieving that greatness. It’s also frustrating to see that MCG has apparently decided to produce ALL of its scenario content in the form of Instant Adventures, which severely limits the scope of the scenario support they’re capable of offering for some absolutely fantastic games.

Bottom line for me: If Bruce R. Cordell offered another collection of 10 scenarios for The Strange, I would scarcely hesitate before dropping $10 on them.

Style: 4

Substance: 3

Author: Bruce R. Cordell

Publisher: Monte Cook Games

Print Cost: $24.99

PDF Cost: $9.99

Page Count: 96

ISBN: 978-1939979439

other species which have become household names only because Cretaceous Resort has summoned them back among the living, like the Chilesaurus, the “Frankenstein dinosaur” which provides a missing link between Stegosaurus and the carnivorous dinosaurs.

other species which have become household names only because Cretaceous Resort has summoned them back among the living, like the Chilesaurus, the “Frankenstein dinosaur” which provides a missing link between Stegosaurus and the carnivorous dinosaurs.